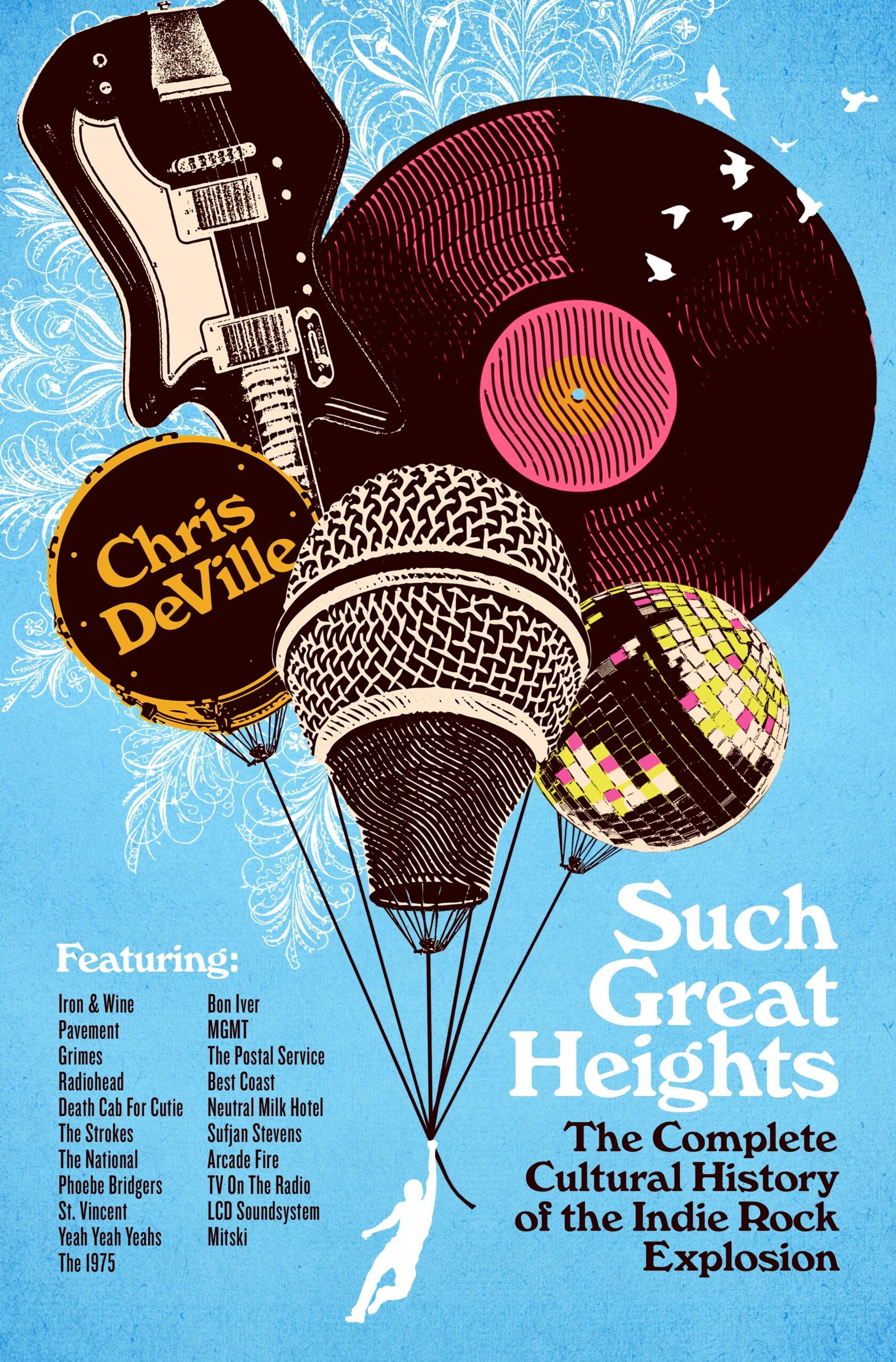

As I read through SUCH GREAT HEIGHTS: THE COMPLETE CULTURAL HISTORY OF THE INDIE ROCK EXPLOSION—Stereogum Managing Editor Chris DeVille’s new book that covers my favorite years in music—I tried everything I could to avoid beginning this review with a quote from LCD Soundsystem’s “I’m Losing My Edge.”

“It will make everyone roll their eyes. Don’t do it,” I kept telling myself, as I tore through chapters mentioning Yeah Yeah Yeahs and the Strokes and other New York bands that rose in the 2000s. “The Internet will call you a hack or an asshole or a pathetic joke. It is 2025, and you are about to turn 40; the people are tired of one of your favorite bands.”

But DeVille even references the iconic song in his text, because how could you not? And ultimately, I would be doing my past self a disservice by not indulging in pretentious self-references, just as James Murphy would. I have no shame and not much of a reputation to ruin, and I sold this pitch on looking at the book from my point of view over the years DeVille covers. I was there listening to the Magnetic Fields’ 69 LOVE SONGS on a portable CD player on the school bus to middle school, learning how to be the worst sort of hipster by watching HIGH FIDELITY in high school, and learning how to be humble in the decade I spent behind the counter of a record store.

“I was there / I’ve never been wrong / I used to work in the record store / I had everything before anyone.”

I was hired at Euclid Records in May of 2004, right as my senior year of high school had ended. I was there, filing away so many CDs and records by the bands in DeVille’s book. While I admit that the young me was so often very wrong, my pretentious high school ass got humbled at the record store. I was there when we had everything before everyone—that much was true. We’d often receive promos for albums, sometimes months in advance of their release dates. (Huge shout out to Sub Pop, who always sent promo CDs early and frequently, each with a press release blurb on the promo-only artwork. Also, shout out to runners-up MERGE and Polyvinyl, respectively.)

The first time I recall hearing the word “indie” was a few years before at a Weezer concert when I was a sophomore. Two girls sitting nearby were labeling everything as indie: the way some hipster was dressed, the band logos on the buttons of someone’s bag, all the horn-rimmed glasses frames, the bands on their shirts. “That’s so indie,” they would say and cackle to themselves, using it like a punchline, almost as if the word itself was too self-serious to be taken seriously. I’m sure I must have encountered it elsewhere in passing enough that I could piece together their sentiment with context clues, but that moment stuck with me.

Before long, I started using “indie” as a catch-all term for the music that moved me. These were bands that required effort to find, records that felt like you uncovered buried treasure if you got to them before everyone else, and songs that blended genres into something familiar yet new. It wasn’t merely a genre label, but the all-encompassing feeling of being on the edge of something different. Music that felt like traveling through the great unknown. I thrived off of handing mix CDs to my friends with my latest finds, carefully crafting each disc with tracks just for them.

DeVille and I are of a similar age, give or take a couple of years. We most likely would have been friends if we had attended the same high school, trading mix CDs of songs we downloaded on Napster, or bands we discovered in someone’s MySpace Top 8, or some free MP3 from a music blog—maybe hitting up some local record shops to purchase stacks of CDs after hearing those mixes. (There’s also a fair chance I wouldn’t have tried to be friends with him for some gatekeeper-y reason like DeVille mentions in the chapter about Hollywood embracing indie rock. I may have had some terrible excuse like he “doesn’t appreciate IN THE AEROPLANE OVER THE SEA as much as me,” or some other pretentiously stupid, made-up reason because I was an angsty, neurodivergent, wannabe-hipster teen.)

Either way, I’ve admired DeVille’s writing for years and was excited to tear through the pages of his comprehensive guide to indie rock, the technology that spread it far and wide, and the pop culture that helped make many an indie band some sort of famous.

I found SUCH GREAT HEIGHTS to be challenging to read, not because of the writing—it’s a comprehensive and fantastic history from someone who lived right alongside it. My issue was based purely on the amount of nostalgia DeVille taps into from my formative years. I kept having to put it down and console myself about getting older. Many of my favorite records are 20 years old or more, which seems impossible for my brain to fathom. DeVille sprinkles in bits from his own life throughout the text, certainly not as much as I would have inserted myself into, but it adds so much to the authority of his words. This dude is an expert. I found myself dog-earing every other page because I would come across something that sparked a memory I wanted to comment back to him on, because I was there too!

SUCH GREAT HEIGHTS felt like reading an extremely entertaining textbook version of my days as a young adult. I never would have guessed that the bands I saw live, the MP3 blogs I refreshed daily, the records I shelved, or the friendships I built around a culture of burned CDs would someday be written about as history. But here it all is—organized, contextualized, and given shape. It’s not only about indie rock, but also about everything popular alongside what was part of the indie underground, how indie music bled into other genres, and how technology helped those fringes slowly become the center for a while. To me, indie always felt like shorthand for anything outside the obvious, the culture that lived on the edge. Now, seeing it mapped out by DeVille, it becomes clear how much those edges reshaped pop culture as a whole.

I was there.

I was there when Sam Beam was releasing songs recorded in his living room. I was there when Iron & Wine started making studio records and leaned into a bit of a jam band thing live. It was the equivalent of when Dylan went electric.

I was there in 2005. I was there when Clap Your Hands Say Yeah played LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O’BRIEN and weren’t signed to a label. We had to order the CD directly from the band. I was there when Clap Your Hands Say Yeah was still unsigned but had made a deal with an indie distributor, and you could buy the CD at Target.

I was there when AHA SHAKE HEARTBREAK automatically downloaded spyware to your computer when you ripped it to iTunes.

I was there when the major labels decided everything was going to be a Dual Disc—CD on one side and a DVD on the other when you flipped it over.

I was there when our label reps said, “It’s pronounced M-G-M-T, not ‘Management.’ DO NOT call them ‘Management.’”

I was there when Santogold had to change her name to Santigold for legal reasons. I have the first record when it was spelled with an “O.”

I was there when Jamie xx made a record with GIL! SCOTT! HERON!

I was there in 2014, handing in my resignation at the record store to take a job that would have me sitting in a cubicle but would pay me enough to survive.

That’s when I started losing my edge.

Comments