Once a year and change, I find myself revisiting Spike Jonze’s 2013 opus, HER. The film is a dreamy and melancholic portrait of isolation, connection, and that liminal gap between the two where self-discovery—I believe—can only be realized. To me, HER is like a weighted blanket: I don’t need it most of the time, but it is indispensable when I do. This is a film that has helped me out of some pits, both emotionally and creatively, and has recently influenced a lot of my own writing. It’s not without its flaws, but I love it all the same.

Intellectually, HER fascinates me for many reasons—chief among them is its unlikely union of genres. On one hand, HER is a romance, a deeply personal portrayal of falling out of love delivered with the kind of lived authenticity you can’t generate from a prompt. There is plenty of great writing out there on how HER is a companion piece to Sofia Coppola’s LOST IN TRANSLATION—which was conceived at the end of that director’s marriage to Jonze—and how both films dovetail into a full picture of their relationship. I do not have a fresh take on this interplay, fascinating as it is, and so I will not fill your head, dear reader, with more such digital flotsam.

The other genre playset HER scatters across its creative sandbox—and the one I’ll be engaging with here—is science-fiction. This is to say, HER certainly was sci-fi when it came out. According to Reddit and Wikipedia and no more reliable source that I can cite, HER is set in the year 2025. Though there is no “canon” way to verify this timeframe, it feels about right for a 2013 prediction of what the world might be like in 12 years. And while some have made a case for this movie being pretentious or maudlin, it’s hard to deny its prescience. HER gets a lot right about the world today; thought-provoking speculative fiction makes an unlikely bedfollow for a raw and tender love story, but HER remains astonishingly relevant in a genre that dates itself faster than any other.

For instance, the surface elements on display are striking. The wireless earbuds our protagonist Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix) and other human users wear to communicate with their AI confidants were groundbreaking examples of conceptual design in 2013, back when spaghetti cords were the norm. A few years later, AirPods hit the market, doubtlessly drawn up from the template Jonze’s film provided. The Bluetooth-powered buds are now ubiquitous reminders of the way our phones are increasingly insulating us from the world around us—it is no coincidence that Jonze was tapped to direct Apple’s commercial for the latest line of devices.

On a deeper cultural level, HER totally nailed our society’s growing dependence on technology—even if some of its nouns are flipped. When the film opens, we learn that Theodore is a writer for “beautifulhandwrittenletters.com,” a service that provides love notes for romantic partners who themselves have not been creatively struck by their muse. In this invisible role, Theodore vicariously participates in hundreds of relationships, pulling strings behind the scenes. Of course, the idea of a human copywriter fulfilling this function (and earning enough to afford a spacious 35th-floor Downtown apartment—ha!) is especially ironic coming from the first modern movie about AI. The dynamic, however, is very real. Humans using technology to author messages they are unable or unwilling to come up with on their own is a wretchedly mundane premise in the era of ChatGPT. Within this framework, Jonze was right on the money in that AI would be positioned to supplant—not support—creativity.

Likewise, Theodore’s AI companion Samantha (huskily voiced by Scarlett Johansson) is more intuitive and empathic than any Sora 2 creation that’s been waved in my face at a party—and, frankly, than most of the humans doing said waving, too. Samantha’s assistance to Theodore is qualified and conditional, without the simpering patronization you’ll get in response to even the most uninspired GPT prompts. She gets angry and jealous and is not at all bound to the whims of her user.

One could argue that by giving her autonomy and a fully-formed personality, Jonze’s AI girlfriend of the future is the antithesis of the worryingly real and subservient ones increasingly used today; I say that Samantha and her ilk’s AI nature belies the broader uptick in parasocial relationships enabled by the tidal wave of podcasts, livestreamers, and social media platforms we’ve seen proliferate the web since HER’s release.

2025’s “Male Loneliness Epidemic” is the newest name for the same pity-party narrative pushed for years by sad fringes of the internet, but it is nonetheless telling of a culture that increasingly prioritizes cloud-based networking over face-to-face interactions. When I recount to friends my disappointments in the dating scene, the response is rarely “Have you tried taking a class?” or “I know a bar that’s great on weekends”—it’s usually some variation of “You should get on [insert app here]!”

Lest I sound like Tim Robinson in a hot dog suit, I should note that I know plenty of happy couples who met on Hinge. My misgivings stem more from the disparity between the idealized, curated version of myself (and others) that will inevitably pale before the awkward reality. Am I engaging with a person or a profile? In the time of AI, how can I even tell?

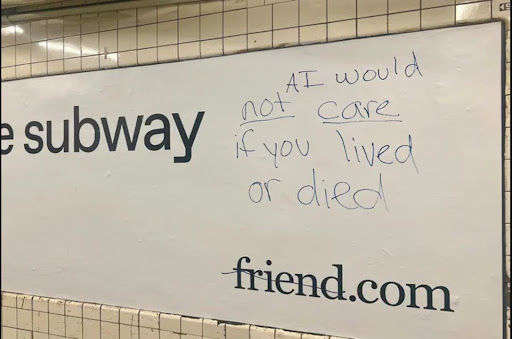

I consider myself extremely blessed to have found a vibrant social circle after moving to the other side of town during COVID, but I know I am the exception. Plenty of my friends have lamented after moving to new cities that they have failed to find a community, the already difficult task of making new acquaintances in your 30s and 40s compounded by the gulf between lived and virtual experience that has only widened since the pandemic. Whether or not you are unsettled by the “Friend” AI adverts plaguing metropolitan centers, the product is the logical consequence of the migration of “third places” from physical to digital spheres. In this sense, HER’s depiction of simulated companionship is all too plausible in 2025.

Time and place are both key to any setting, and HER is geographically set in (predominantly Downtown) Los Angeles, or at least a pie-in-the-sky vision of what it could have looked like in 2025. This is the other realm of speculation I love about this film. I’ve lived in or adjacent to the City of Angels my whole life, and mountaintop log cabin fantasies notwithstanding, I will likely die an Angeleno. Yet despite three decades of exposure to this landscape and my resulting desensitization to urban blight, I still delight in seeing depictions of my hometown on the silver screen.

The mystique of living in the most-filmed city in the world is that you can see the same streets you walk every day through a countless array of diverse lenses. It’s a humanizing and humbling experience in a city that gets a solipsistic rap from outsiders who will understandably interface with it primarily through the double-laminated safety glass of a Waymo windshield. This may not be the way you see the city, but then your perspective isn’t the definitive viewpoint, either.

Despite the liberal use of cutaways that were shot in Shanghai, HER is very much an LA movie, albeit one that envisions a possible future for the city. “LA in the future” is hardly a novel backdrop, but where BLADE RUNNER 2049 puts everything west of the 405 beneath the Pacific Ocean and ELYSIUM’s rubble-strewn hellscape is most reminiscent of a FOX News bumper about the Mexican border, HER paints a more flattering alternative—one that is in no objective or subjective sense rooted in reality.

While HER’s projection of AI’s impact is eerily spot-on in its accuracy, its framing of the city is purely rose-tinted fantasy. This is a Los Angeles devoid of trash, decay, or poverty. There are no construction crews tearing up miles of road, nor is there a single homeless citizen strewn across any of the spotless, walkable sidewalks Theodore struts down. Even the smog takes on a warm radiance that makes the cityscape appear like it’s floating in the clouds. HER’s futuristic take on LA is unique in its hopefulness; the utopia it posits is the only screen version I’d want to live in.

Case-in-point: the way LA public transportation is depicted in HER. Outside of a brief insert where Theodore calls a cab for his sex surrogate with Samantha, there is not ONE (1) car shown in the movie. This Los Angeles is not only walkable via skybridges (thank you, Shanghai), but also fully connected by light rail. Throughout the film, we watch Theodore get around not only DTLA, but Santa Monica, Dockweiler Beach, and West Hollywood from the comfort of an LA Metro train seat—all destinations which are incidentally real-world bastions of NIMBY resistance to Metro expansion plans. Just peep this very optimistic route map Theodore walks past around the 10-minute mark:

To HER’s credit, there has been an Olympic effort by the city to lay down some rail ahead of LA 28, and this year did in fact see the opening of the long-held-impossible LAX transit center. Still, the existence of infrastructure and its accessibility are two different beasts. Yes, you could replicate Theodore’s car-less trip to the beach from Downtown, but the process will not be quick, easy, or enjoyable. As much as I wish otherwise, LA’s Metro is not the intuitive utility of Paris or New York, let alone the dreamlike conveyance of HER’s future.

To HER’s credit, there has been an Olympic effort by the city to lay down some rail ahead of LA 28, and this year did in fact see the opening of the long-held-impossible LAX transit center. Still, the existence of infrastructure and its accessibility are two different beasts. Yes, you could replicate Theodore’s car-less trip to the beach from Downtown, but the process will not be quick, easy, or enjoyable. As much as I wish otherwise, LA’s Metro is not the intuitive utility of Paris or New York, let alone the dreamlike conveyance of HER’s future.

Then there’s HER’s bustling skyline—one where Downtown LA’s cluster of highrises has seemingly extended all the way out to Baldwin Hills (thanks to VFX magic and, once again, Shanghai). There’s actually a precedent to this densified forecast: the 2010s saw a boom in big Downtown developments, many from Chinese investors. Take Oceanwide Plaza, a Beijing-backed project which broke ground in 2015: three giant towers next to Crypto.com Arena zoned for residential and retail space—not to mention a two-acre park elevated nine stories above ground. Oceanwide promised to be a city-within-a-city, the kind of stuff ripped right out of HER’s numerous and scenic rooftop locales.

Today, the towers stand unfinished and abandoned: Trump’s trade war with China saw the money men pull out in 2018 after putting down just $600M of a $1B+ investment. The developments are now more popularly known as the “Graffiti Towers” for the plethora of tags sprayed over every neglected surface. While there are prospective buyers who would see the construction through, the towers are emblematic of cooled interest in Downtown expansions in the face of restrictions on offshore funding.

Science-fiction is the art of extrapolation. You look at your hopes and worries of today and wonder what they may look like tomorrow. Is that a future you want to live in? Is there anything you can do about it?

HER’s Los Angeles is a paradox that was conceived to be precisely what it can’t be in real life. I think that is what makes its setting such an appealing love letter to LA—one that is intimately aware of what it feels like to live here while flouting its mechanical limitations. It’s what allows an intersection in China’s largest city to pass somewhat convincingly as Figueroa and 7th; it’s also why Jonze’s depiction of social and physical seclusion feels so apt. Obviously, creating a believable future scenario was not going to be the top priority for Jonze’s autobiographical tale. The fact that he did anyway is a testament to the film’s human heart. AI cannot currently emulate a personality as believable as Samantha’s, but it will—and in less time than you or I can anticipate.

I take some comfort in that. I’d sooner place my trust in an artificial empath than flesh-and-blood robots like Sam Altman. In that vein, I can hold out some hope that maybe even Jonze’s dream for Los Angeles—while not yet feasible—may too eventually come to pass.

Comments