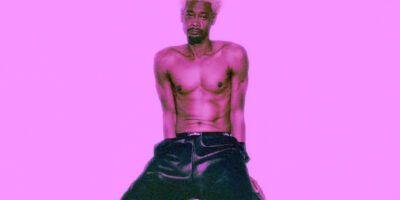

Eight months after releasing the audio equivalent of the 2017 Cleveland Browns, Marshall Bruce Mathers III decided the world had not heard enough, and chose to surprise drop KAMIKAZE. Eminem’s 10th studio album begins with the sound of a plane crash—the perfect summation of the following 46 minutes, the shortest runtime of an Eminem studio album since 1999 and pretty much the only admirable quality of this album. The rest of the opening track is an exhausting five-and-a-half minute screed in which he takes shots at mumble rappers, music journalists, and the freaking Cheeto in Chief. That’s right folks, the self-proclaimed greatest of all time noticed that our big, wet President is orange, and Eminem seemed dead set on challenging him to a freestyle battle. Even the self-aware moments on “The Ringer” are tremendously grating, like “I said my beef is more meaty, a journalist / Can get a mouthful of flesh / And yes, I mean eating a penis.” Cool.

The following 12 tracks are a convoluted mess that boils down to Mathers’ only care in the world: being loved. He can’t go more than 30 seconds without complaining about album reviews and mumble rappers, the latter of which he critiques while simultaneously using instrumentals and flows that are hallmarks of the genre. “Not Alike” is a half-assed quasi-parody of Migos’ “Bad and Boujee,” but halfway through he abandons the parody and is just rapping in his signature style over a cheap knockoff instrumental. It’s as if a senile Weird Al Yankovic forgot where he was mid-recording and made an earnest song instead. Inconsistency is one of the few consistencies on the album and paints a sloppy picture of a megastar so divorced from reality that KAMIKAZE becomes something of an anthropology artifact. The jarring hypocrisy of nestling an apology track like “Stepping Stone” into an album in which he spits a slurry of slurs is something to behold. His choice to pay homage to the Beastie Boys’ LICENSED TO ILL in both album artwork and homophobia is ignorant and tone-deaf, especially considering that the Beastie Boys apologized for the offensive content on their record in 1999.

But this has always been how Eminem operates, crossing the boundaries for no reason other than stirring up controversy. The formula has depressingly proven to be tried and true: KAMIKAZE is his ninth consecutive Billboard number one record, a streak that will likely continue until he finally decides to mercifully stop. He’ll never learn anything, because what is there for him to learn? If he can churn out garbage like this in perpetuity, what will ever convince him to call it a career? Mathers is convinced that chasing the dragon of a critically beloved record is a worthwhile pursuit, especially when the paychecks are so reliable and each incendiary review adds to the lore of the outsider persona he has crafted over the past two decades.

But the truth is he is not an outsider and he never has been. He managed to market his whiteness as a minority, a figurehead for a counterculture. But that was a lie from day one. Eminem brought the monoculture into hip hop—a black-dominated space which had been a genuinely subversive counterculture since its inception. That imprint of intrusion will last far longer than he will.

And it seems we will have to wait quite a while for Mathers to stop making slam poetry for dudes named Chase McMacklemore with Eminem tattoos in the Monster Energy font, because there is clearly a large enough audience for these albums. That’s a problem that is out of his hands. It’s an indictment of the current music and cultural landscape that values nostalgia, reboots, and established franchises over new, fresh, innovative ideas. Eminem proves that everything has an expiration date. Most, or at least enough, will trick themselves into drinking the spoiled milk in the interest of convenience and familiarity. The first step is to do what I didn’t, and just ignore him. Eminem has nothing new or interesting to say, and it’s hard to imagine he ever will. That’s not all entirely his fault, most artists hit a creative wall and fade away, but Eminem is at a level of superstardom that may not fade in his lifetime and thus we’re probably stuck with him for decades. Some blame has to be put on his inner circle as well. How the title track on this album made it off the cutting room floor is a mystery on par with DB Cooper.

One day Eminem will call it quits, but until then he’ll keep serving us a not-so-hot gas station coffee pot.

Comments