This article previously appeared on Crossfader

It’s been a hot minute since I first discovered INDIGO PROPHECY (known as FAHRENHEIT in my neck of the woods, ironically a country that uses the metric system). At the time I knew nothing of the interactive cinematic genre, and only began to see its worth through repeated playthroughs of the game’s demo. Few video game levels hooked me quite as much as the murder-cover up that INDIGO PROPHECY opened with, our protagonist shocked to discover that he had killed an innocent man in a diner restroom.

Over the last dozen years, we’ve been treated to an increasing number of choose-your-own-adventure games; interactive experiences styled after the books you and your friends clamored for in elementary school. But not unlike these books, games of this ilk still suffered a cardinal setback: they didn’t respect who the player wanted to be, they simply built the illusion of it. Though play afforded us variety, plot threads were still tightly railroaded.

Death is one example of a concept that hasn’t made the most graceful transition to the interactive format. Having a character die, even by player choice, is still seen as a loss. While an NPC being eliminated from the narrative can reward the player by stoking the drama, it often comes at the price of removing scenes associated with that character, rather than writing new ones around them. Players must choose between a more exciting game or simply more game, rather than having both.

Still, it could be argued that it’s about the journey, not the destination. Perhaps nowhere is this better illustrated than in the works of David Cage. From INDIGO PROPHECY all the way through his latest entry, DETROIT: BECOME HUMAN, Cage’s projects tell the kind of stories we’d see in a haphazardly written Syfy mini-series. Dire murder-mysteries with a penchant for the absurd, these games were never bad so much as disappointing, thrillers that nailed the takeoff but failed to stick the landing, their gameplay too monotonous, cutscenes too indulgent, and narratives too . . . weird.

The most normal thing to happen in INDIGO PROPHECY

I’ll say this: Cage is really onto something with DETROIT. His game is not unlike the rest of his entries, immediately captivating but littered in content I have no interest in playing for a second time. As much as I appreciate the immersion of playing a housekeeping android, a minute-long cutscene would be preferable to three entire levels dedicated to serving people breakfast and dinner.

When DETROIT finally does kick off, it’s Cage at his very best. Perhaps that’s because the man has really spent his entire career making the same game over and over again (you can only make a playable version of THE FUGITIVE in so many ways), but in any case, it’s clear that he’s learning something from all these stories. If Cage’s latest was half as long but twice as branching, then we’d have a true modern classic on our hands. As it stands, DETROIT is a clunky, but compelling, exercise in twisting narratives—messy tone shifts and genre-bending included.

As indulgent as DETROIT can be, Cage certainly knows how to leverage its action sequences to their maximum potential, and it has everything to do with smart world-building. Many games use lethal stakes to communicate the irreversible nature of their fail states, and while DETROIT does feature its fair share of gunplay, the artificial nature of its android protagonists means that the story doesn’t need to stop when our pulse does. If robot detective Connor gets clipped by a rogue android, his manufacturer will just roll out a new model at the next crime scene. It’s an ingenious way to encourage ballsy choices as well as maintaining the story’s momentum, but it could do a lot more yet.

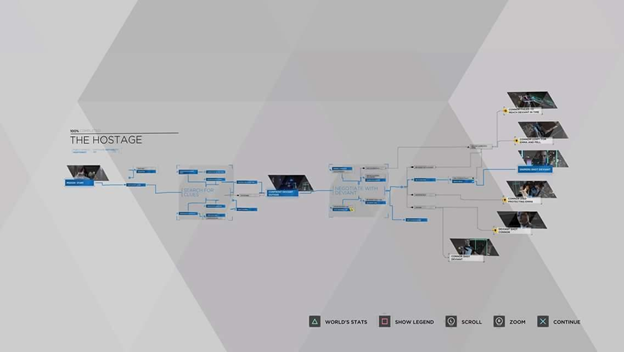

Go ahead, make my game

A brief detour to better illustrate my point. After years of designing projects aimed at bridging the gap between film and gaming, Cage’s greatest accomplishment with DETROIT lies in its flowchart, a branching tree that beautifully illustrates the various endings of the game’s many levels. It’s the first time in a Quantic Dream game that cinematic immersion is actually interrupted in favor of player statistics, openly transparent about how much weight our decisions hold. As a result, DETROIT can’t hide behind the smokescreen of fake consequences.

Just looking at the flowchart, one begins to realize that most of DETROIT’s final scenes hinge greatly on your choices made in prior sequences: who lived, who died, and how all this violence has affected everyone’s viewpoints. No longer was I skeptical of the game’s possible outcomes, because they were laid out before me. But most importantly, I felt that the game was proud of its narrative complexity, and unafraid to own up to the title of being seen as a video game, fully embracing the artifice of its medium.

What lies beyond the curtain

The flowchart seemed to indicate that any available ending was just as valid as the next. As such, DETROIT stands out as a rarity in its genre. Where dying halfway into UNTIL DAWN or HEAVY RAIN felt like losing, DETROIT is never quite as black and white with its choices. However, as successful as the flowchart is in showcasing the game’s countless outcomes, it’s frustrating that certain playstyles are still seen as a fail state of sorts. Letting the game’s detective character fulfill his in-game mission shouldn’t be seen as bad gaming, yet Cage seems to actively discourage the player from doing the ethically wrong in favor of the narratively contrived.

This begs the question why Cage doesn’t allow his game to embrace its branching paths even further. As much as I try and alter the outcome, Cage’s desired playstyle always lingers in the periphery of his design. I know he wants all three of my playable robots to rebel, but what if I don’t? What if my Android revolution has killed hostages and bombed innocents to make its statement? At that point, can Cage really still wag his finger at me for siding with the regime its trying to overthrow?

Well, okay, if you frame it like that . . .

Narrative freedom doesn’t mean much if it comes with admonishment attached to it—you might as well just give me a “Game Over” screen if you’re going to punish certain choices anyway. Killing off characters in UNTIL DAWN shouldn’t be seen as a failure—one could argue teen slaughter is the whole point of a slasher—rather, it should be a vital part of its storytelling. A character dying in LIFE IS STRANGE shouldn’t mean cut content——just different content. Unlike the games that emulate them, film and TV series don’t suffer from high body counts, but rather up the drama through them. The same should apply for the genre across mediums.

DETROIT is better at accommodating this kind of playstyle than many of its peers; the narrative is designed in such a way that certain significant characters can be removed from the equation and the show will still go on. But not all paths are created equal—you can still finish the game under any route, but certain endings are more complete than others. Rather than simply give everyone a seat at the table, I’d like to see developers give players equal access to the menu as well—desserts should not be limited to just the good kids. What the likes of Telltale, Quantic Dream, and Supermassive Games need to do is let the player be whoever they want, with no objections from the developer.

From Telltale’s Walking Dead entries to Dontnod’s LIFE IS STRANGE, there is something out there for everyone. Fighting for the Iron Throne and playing a bi-curious teenager are all within the realm of possibility for the genre. Let’s hope that as the branching narratives of these games continue to grow, developers begin to entertain a broader diversity of narrative approaches, letting players live in their worlds, but still putting enough pressure on the gamer so that we don’t forget how greatly our actions can ripple into uncontrollable outcomes.

Comments