Bruno Faidutti is one of my favorite game designers, not just for the games he’s developed but for his insightful blog posts about his relationship with publishers, the prevalence of nature-themed games, and the process of writing and translating rules. His ethos of chaos and flashy special abilities are a recipe for good times and a refreshing break from the modern-day trends toward multiplayer solitaire. Sadly, the game that put him on the map, CITADELS, has dimmed in my view despite being similar to many games I enjoy. Over time, its cutthroat interactions and variable endpoint do not gel together, especially when the mechanics are simple and do not support a potentially one-hour-long game.

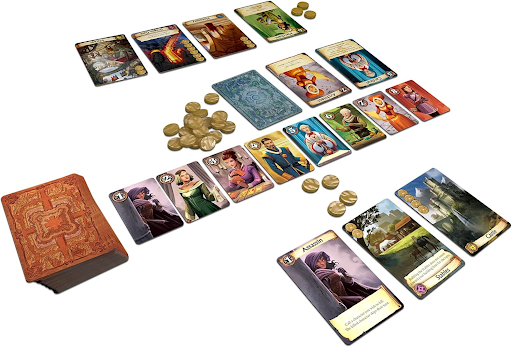

Interaction is a divisive concept, but even those with a fanatical hatred of player boards might find CITADELS’ tools of treachery off-putting. The hook of CITADELS lies in a role selection system; the starting player picks a role and then passes the remaining options to the following player until everyone has chosen. The characters are numbered one through nine, which are called out to determine turns, so the person who picked number one goes first. On a turn, players either draw two cards and keep one or take two gold, potentially build a building, and then activate their role’s effects. Some positions allow players to gain more resources, but these are boring compared to the game’s mean choices. You can steal gold with the Thief, swap hands using the Magician, call upon the Warlord to destroy buildings, or skip someone else’s entire turn with the dreaded Assassin.

This last component is a commonly cited reason for disliking CITADELS, because those are mechanics traditionally reserved for UNO or other lazy card games that hardcore board gamers like myself consider “beneath” them. However, the interaction in CITADELS is more interesting than simply playing a skip card on someone. Instead of calling someone’s name to target them, players must declare the specific role they are targeting. That guy has five military buildings in front of them, so they must’ve chosen the Warlord to gain money from them, only to try to target them and find out they tricked me by picking another role. This bluffing has helped CITADELS remain relevant and respected in the hobby.

UNO would be a lot more tolerable if games did not have the chance of stretching out to the 90-minute mark because it’s evident who is winning, aka the person who is about to run out of cards, and, thus, who needs to be targeted. This phenomenon is known as “crabs-in-a-bucket,” where a player pulls out ahead of everyone else and is pulled back to the median by their opponents. MUNCHKIN is one of the clearest examples; as a player approaches level 10, their opponents are less inclined to help them with encounters and more likely to strike them down with negative effects, prolonging the game because it’s rare to solve encounters on one’s own. Larger area control games like INIS that require a player to reach a certain metric to win are especially vulnerable, especially because INIS makes you declare you are about to win, throwing up a big neon sign telling everyone to pile on you.

Giving games a fair sense of finality is difficult. You don’t want the game to be too long and overwhelming, nor too short and unfulfilling. The old-school design philosophy of playing until everyone else is eliminated a la MONOPOLY and RISK has been replaced by two paradigms: playing until someone reaches a certain threshold, either of points or available resources, or a set number of rounds. Two of the biggest games in the past five years, LOST RUINS OF ARNAK and EVERDELL, threw a monkey wrench into the conversation by having players end at different times; I could keep building up my tableau for up to 20 minutes after everyone else had finished. Some designs benefit from not knowing when the game might end, such as ETHNOS hypnotizing you with the promise of larger bands, only for someone to draw that third dragon and leave you with 10 unplayed cards. On the other hand, GRAND AUSTRIA HOTEL is a heavier Euro in which you will want to do everything. Yet, the game only takes 14 turns and forces you to make tough sacrifices.

CITADEL ends when someone completes seven structures. It seems easy until other players steal your money, destroy your buildings, or even skip your turn if they notice you accelerating toward ending the game. Drawing off the top of the deck blindly and being unable to build duplicate buildings adds to the grind. The publisher is clearly cognizant of people’s complaints about length because the original rules required completing eight buildings, with seven as an option for a shorter game. In contrast, newer printings have seven as the standard.

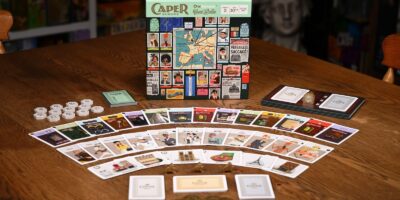

MISSION RED PLANET, a Faidutti co-design, and LIBERTALIA are two of my favorite games that involve pettily poking and prodding one another. Both feature flashy characters and outthinking your opponents with clever card play, but, most importantly, they end after a set number of rounds. I can see who’s winning and contest them by stealing their loot or taking areas of Mars from them, but doing so will not extend the game in any way. Even though both games on average are longer than CITADELS, they can’t fall victim to crabs-in-a-bucket and have never felt longer than what the gameplay offers.

I must admit, I own another Bruno Faidutti product with vicious backstabbing that also lacks a fixed endpoint and features players fighting for a specific point total, FIST OF DRAGONSTONES. So, what’s the difference? Aside from the role selection, CITADEL’s mechanisms are pedestrian. Draw buildings or get money, spend money to build structures, rinse and repeat. Some districts have extraordinary abilities but are relatively expensive, and you have to draw them in the first place. In contrast, FIST’s auction and different currencies are so engrossing that I’m alright with the game going a little longer.

WIthout the bluffing and character abilities, the building system in CITADELS is not compelling enough after the fifth or sixth incident of someone needing one more district to win, only for them to get hit with a metaphorical Blue Shell and pulled back to the mean. I love the idea of CITADELS and have nothing but respect for its designer and his ethos, and my reasons for disliking it are not due to its interactiveness like many other people. The crabs-in-a-bucket phenomenon is at its worst with this mix of cutthroat action and variable endings, especially when the mechanics are simple and grow stale when repeated too often.

Comments