The brilliant Irish comedian Dara O’Briain has a bit about why video games are the greatest of all entertainment industries. He argued, “you cannot be bad at watching a movie or listening to an album… but you can be bad at playing a video game.” Some have countered this routine by claiming many people are poor media analyzers, hence why “Born in the USA” still pops up at right-wing political rallies, and “Every Breath You Take” remains a wedding staple to this day. But claiming George Orwell would see your transphobic screed getting banned as evidence of Big Brother does not prevent you from reading ANIMAL FARM or DOWN AND OUT IN PARIS AND LONDON. If you are bad at a video game, or by extension a board game, you will not be able to complete it and therefore experience its creator’s full vision.

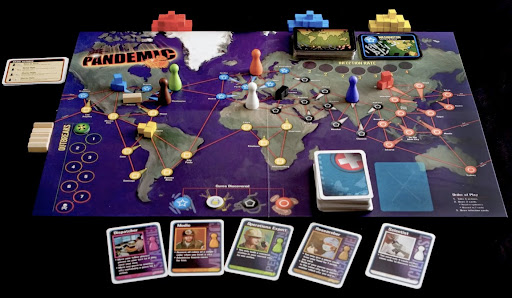

The infamous CUPHEAD IGN video is the most extreme example of the debate over how good of a gamer you have to be to get a say on them, as the counter to any negative review becomes “well, just get good” or “you weren’t playing it right.” DARK SOULS and PANDEMIC have inspired developers to create more challenging products in their respective mediums. But the difficulty in PANDEMIC and its descendants comes more from RNG (random number generation), a constant in nearly all board games magnified tenfold as you hope to get the right cards and that you don’t flip Mexico City and immediately lose. Despite the fact that a few failed dice rolls can end the game through no fault of the players, the presence of these variables makes it all the more sweeter for gamers who figure out the puzzle, map out the final plan, and execute it successfully even as the odds are stacked against you. Furthermore, there are ways to make these games more palatable while maintaining nail-biting tension. MASTERS OF THE NIGHT, an aesthetically pleasing fusion of PANDEMIC and vampires, does not have any of these difficulty mitigators as poor rules guides, more randomness, and limited options make the game even more frustrating and unfun.

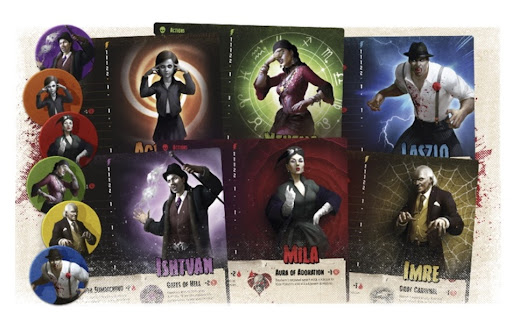

I was attracted to MASTERS OF THE NIGHT’s SIN CITY-esque aesthetic and color palette, with grim, black-and-white offset by bright blood reds. You play as one of several vampires waking up in a new city, trying to rebuild their empire as agents hunt down and fight you. Each of the vampires seemed interesting, with compelling combo potential between each other. The goal of using minions as part of your fight, creating sigils around locations to gain more powers there, and finally sacrificing the minions in a massive blood ritual to take over the city sounded awesome. The coolest part of the production had to be the event deck and veil tracker, a form of health that you are constantly trying to balance. These components feature old-timey newspapers explaining the game’s plot, with classic titles you can imagine being read out in a Mid-Atlantic accent, and the events feature more and more blood as you draw deeper into the deck. It’s an inspired, thematic artistic decision that I’m surprised more games don’t emulate.

Speaking of the deck, this is one of the core features of most cooperative games. Flipping over a card from a deck tells you where to spawn diseases in PANDEMIC, flooding in FORBIDDEN ISLAND, and vampire hunters in MASTERS OF THE NIGHT. In each of these games, you don’t want these threats to build upon a space. In PANDEMIC, spawning three cubes in the same city will spread disease to adjacent areas; if these outbreaks happen too often, you simply lose the game. In ISLAND, tiles flooded twice will fall away and prevent you from reaching the necessary treasures to win. The gimmick of MASTERS OF THE NIGHT is a veil that prevents society from seeing the vampires; if vampire hunters spawn on a location with a vampire on it, the veil decreases, and the game is lost when it hits zero. Again, it’s a thematic core mechanism that takes from existing properties yet adds a fabulous sheen. On paper, this should work.

A large part of the randomness of these games comes from drawing from this deck, but PANDEMIC and FORBIDDEN ISLAND alleviate this somewhat by adding a discard pile. You can see what locations have already been drawn, so you don’t have to worry about disease or floods spawning there immediately. There is the chance of the discard pile being reshuffled and that location being drawn later, but players are aware of this and can choose to risk neglecting the site while focusing on more pressing concerns. The biggest flaw with MASTERS OF THE NIGHT is that each card spawns agents on multiple spaces, so there is no way to search through the discard pile and know which locations have a higher chance of being safe. It is entirely random what card you draw and where vampire hunters spawn. Yes, at specific player counts and veil levels, the player gets to choose where to place the hunters between a couple spaces, but this goes away once the veil decreases enough and is not enough of a band-aid for this fatal design mistake. Without the discard pile, the only risk-taking is whether to spread out your vampires and minions or keep them contained, and it’s nearly impossible to win while turtling because you need to kill a lot of vampire hunters to win the game.

This lack of a discard pile to help foresee future cards also shows up in HORRIFIED, another horror-themed cooperative game in which you fight classic movie monsters. It can be similarly frustrating when a villager gets spawned on the board in a random spot, only for Dracula to kill her and decrease the game’s equivalent of the Veil in the Terror meter. However, this is where action points come into play. In HORRIFIED, PANDEMIC, and FORBIDDEN ISLAND, most characters have 4 actions to spend each turn (several roles even have 5). In MASTERS OF THE NIGHT, players only have two.

Furthermore, some activities take 2 action points, so your entire turn can be spent on 1 action. You rarely feel like you’re progressing as more and more agents get spawned, and the veil continues to dwindle as your entire turn is wasted generating one minion to try to stop the bleeding. This strait-jacket feeling means you need a perfect plan and can’t misuse a single action, and even then, spawning an agent in the wrong place will thwart that plan, and you could never have predicted where they’d appear.

Another aspect of difficulty is learning to play in the first place; are the rules intuitive, is the rulebook well-laid out and clear, etc. Kickstarter games, in general, have a terrible track record with this, as they frequently lack the discipline to streamline the mechanics or structure the rulebook so it works both for those with the base game and those with extra tidbits and expansions. Fortunately, MASTERS OF THE NIGHT does not have this problem; I could teach the game pretty quickly to someone, and the character cards do a good job laying out the various actions you can take. However, the game does feature many tiny rules that can be hard to remember, such as when to move the veil and activate all the locations in order. Board games typically deal with this through an index card-size rules guide handed out to each player or a quick summary on the back of the rulebook for easy reference. Sadly, MASTERS does not have either, so there were several points where I missed a small interaction and had to either reset the game or continue on and hope not to make the same mistake again.

A frequent problem in co-op games is “alpha gaming.” Basically, it refers to when one person simply tells everyone else what to do. This is not merely giving advice or everyone putting their heads together to strategize a victory; it’s when 4 players are no longer playing, and it’s one player puppeteering everyone else. The problem is that MASTERS OF THE NIGHT is so punishing and demanding that, unless everyone is a master, it practically facilitates alpha-gaming to have the slightest chance at winning. I was initially attracted to the game because it had a five-player option, the typical size of my friend gathering, and one past the standard upper limit for most other games. Yet, I was terrified to introduce it to them due to this phenomenon.

PANDEMIC and FORBIDDEN ISLAND hit that sweet spot of being challenging yet digestible enough to break into the mainstream. They managed to reach those who look at the boards to TERRA MYSTICA or WAR OF THE RING and recoil in confusion, despite how many people lose while playing them. By making the rules more fidgety, piling on more randomness, and making the game more restrictive, MASTERS OF THE NIGHT does not have the same appeal. A lover of more tactical games might have fun with the more severe difficulty, yet the randomness will put them off. There’s nothing wrong with being derivative, but MASTERS OF THE NIGHT lands on a new identity that leads to little obvious appeal. It’s the wrong way to make it difficult, and you don’t have to be a fantastic gamer to realize and call it out for that.

Comments