I do not like cooperative games. The churlish retort to such a brazen statement is that I don’t like working with others, but I regularly teach games up to three times a week. Invariably, these involve working with people to help them through misconceptions or identify a strategy. Instead, cooperative games frequently fall flat for me because they promise something they do not deliver; a puzzle. Instead of feeling satisfied by coming up with a clever solution—the thing I want from a puzzle—they beat you down with artificial difficulty in the form of boring event decks to inject ‘spice’ into what are often lifeless exercises.

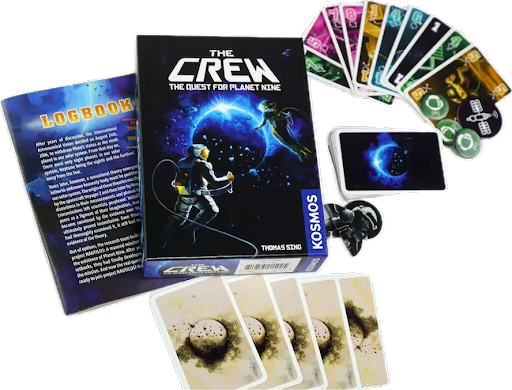

Further iterations on this genre have tried to remove the randomness in favor of limited communication being the main roadblock to success. Still, these suffer from tedium and finicky rules that result in restarting the game more often than finishing it. Of this new wave of cooperative puzzles, only THE CREW has titillated my brain with clever communication, the satisfaction of figuring something out as a team and being able to teach people easily by being grafted onto another genre.

When discussing cooperative games, I’ll really be discussing two categories. The first, spearheaded by PANDEMIC, has players working against an event deck that controls the force they are fighting against, ranging from fire to horror-movie monsters to colonial invaders. Players are free to share resources or strategies as they split their attention between cleaning up short-term threats and forming a long-term strategy while the game beats down on them with seemingly insurmountable odds. In the second category, spearheaded by HANABI, the threat comes not from an external force but from the players themselves. They must navigate communication limits and deduce what others are telling them to accomplish some sort of task, be it arranging a house properly, navigating a mall, or identifying a murderer with the help of a ghost.

THE CREW fits into this second category. It’s a trick-taking game; the first player puts out a card with a number and suit, and the others must play a card of the same suit if possible. Whoever plays the highest of the leading suit, or the highest of the trump suit, wins the trick, then starts the process again. Before each hand but after the entire deck is dealt, players will delegate mission cards among themselves that tell them the specific cards they need to win to accomplish the mission. Players must keep their hands hidden and may only communicate one of their cards; the team must deduce what each other is doing by observing how the rounds play out.

Cooperative games are often described by proponents as puzzles, where players must work together to deduce a solution. If all participants had full knowledge of every aspect of the puzzle, it would be quite easy to solve. The two categories have radically different solutions to dealing with this problem. PANDEMIC offspring add a big chunk of randomness and obstacles to get between the players and the solution, which often feels cheap and unfun for me, while HANABI-descendants give each participant in the puzzle a piece of the full picture to try to get players to build a full whole through deduction and communication.

Said randomness often manifests in a ‘disaster deck’ from which bad things spawn across the board. Event decks are something I dislike even in competitive games, as they feel like a lazy way to introduce unknown variables. However, there is a right and wrong way to go about them. PANDEMIC’s deck is composed of every location on the board; if a city is in the discard pile, then players can hedge their bets and focus their attention on other areas. Other titles, like MASTERS OF THE NIGHT, do not replicate this feature, making it impossible to calculate risk since you don’t know the odds of an area being attacked. It’s no longer a puzzle at that point, it’s just crossing your fingers and hoping you survive.

Board game designers have made many advances in the intelligence level of a board-game-controlled opponent, which is still a far cry from the deck of cards that you fight against in most cooperative games. If you play against a human opponent, they can think and react to your moves, which the disaster deck cannot. It impacts play not through cleverly disrupting the players like a well-designed video game ai system, but by artificially increasing difficulty by putting more and more roadblocks in the opponent’s way. It’s not satisfying to outplay or get defeated by such a mindless enemy.

Since I prefer playing against or with a human opponent, HANABI should be right up my alley, but instead, it feels like pulling teeth as I tell people how to succeed at the game. Players face their cards away from themselves, so they must rely on clues to tell them what is in their hand so they can lay same-colored cards in numerical order. The issue is teaching people when to give clues and how to interpret their information, as cooperative games involve instructing players not only how to play the game but also how to do well. It can easily turn into me playing the game for them or getting frustrated at them for not understanding my shrewd hints, which is not fun for anyone.

Most people have played at least one trick-taking game in their life, so they understand the reasoning behind getting rid of an entire suit in your hand or counting cards to figure out what their Blue 4 is the highest card of that color left. Making the leap from competitive to cooperative can be a challenge for some, but using pre-existing genre knowledge makes teaching strategy a lot easier.

Communication limits are important to HANABI-descendants because, without those limits, there is not much of a game. These can be a challenge to outline. THE MIND, for example, is meant to be played with no communication, yet each group that plays it seems to have its own rules about what that encompasses. Can you make facial expressions to indicate your opinion of a move? It can also be tricky to remember all the information other players give you in HANABI.

THE CREW has a brilliant communication system that is clearly defined yet opens up huge possibilities. Once per round, a player may play a card from their hand to indicate whether it is the highest, lowest, or only number of that suite. This is the only direct information that is available to the players, aside from the first player each round being the one with the highest of the trump suit. The rest must be deduced from that single card and how each hand plays out. My opponent needs to win the Red 4 yet just indicated they only have the Red 5, how do we win from here? Rarely have I felt so mentally stimulated than when using this messaging system to overcome long odds like these to succeed.

PANDEMIC-esque cooperative games promise a challenge that must be solved through long-term planning and agonizing short-term sacrifices, yet they feel cheap and unfair to compensate for open information and a mindless enemy driven by a bland deck of cards. Having your teammates be the main obstacles in HANABI-descendants was an easier sell for me, but they ended up more finicky than fun. THE CREW hit all the right buttons for me by being easier to teach through people’s familiarity with a classic genre and a clear communication system that felt so fulfilling to use. Every time I play it, it feels like a unique puzzle that can always be solved no matter how impossible it seems, and that’s a lofty accomplishment none of its peers have achieved in my eyes.

Comments