This article previously appeared on Crossfader

In the days leading up to NASIR, Nas’ long-awaited follow-up to 2012’s underrated LIFE IS GOOD, I, and I’d imagine a large contingent of hip hop heads, were hoping that there would be something, anything, that would address the allegations of mental and physical abuse presented by his ex-wife Kelis. LIFE IS GOOD, for whatever it had been worth, offered songs about the end of that marriage, messy as it was, and it didn’t seem far fetched that he would again use his platform to, after months of silence, address his ex-wife and the rap world at large. Whatever NASIR was going to be it would never, or even possibly could never, give any answers or make her detailed accusations any less harrowing, but at least there’d be some self-admonishment and confession of his actions.

NASIR doesn’t deal with those accusations, and with each passing track the weight of those allegations can be felt—a lingering tension that builds and builds. In a different time, thinkpieces, Twitter, and the music world at large would be tackling other moments on this album, like when Nas falsely claims Fox News was started by a black man, raps about being an anti-vaxxer, or spits lines about Abraham Lincoln getting too much credit for freeing the slaves while Kanye “Slavery Is A Choice” West builds his beats—Nas’ domestic abuse aside, NASIR is its own brand of problematic.

But as an album that fails to really address the issue at hand, an issue so large it eclipses the album itself, NASIR doesn’t even really justify itself as an honorable sidestep. There was always a potential narrative where Nas records an album so politically charged, so of-the-moment important, so affirming of his generational talent and his importance artistically and socially to the world at large, that his position as a figurehead in the rap community would have overwhelmed his role in the #MeToo moment. We’ve seen far less substantial art be elevated above controversy in the last year. ABC revived Roseanne Barr’s TV show. TJ Miller got a check for DEADPOOL 2. We, and everyone else in the world, listened to and debated Kanye West’s YE. Listening to NASIR, you can almost feel its creators banking on our our goldfish memories colliding with something quote-unquote “important.”

That narrative didn’t happen though.

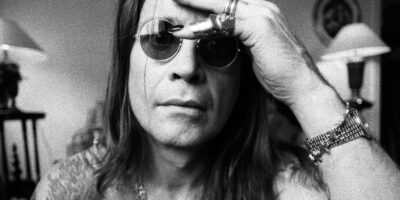

That Slick Rick sample on “Cops Shot The Kid,” that striking Mary Ellen Mark album cover, lyrics like, “SWAT was created to stop the Panthers / Glocks were created for murder enhancement” (“Not For Radio”) or, “Listen vultures, I’ve been shackled by Western culture / You convinced most of my people to live off emotion” (“everything”), all of it points to an album that truly believes it’s more important than it actually is. A year ago, a Nas album would’ve been a theoretical footnote to the era we live in, a sign of the times from one of rap’s greats. As one of the genre’s most important elder statesmen, it would have been an opportunity to see an ILLMATIC for the Trump era, an affirmation of blackness and a commentary on racism, police brutality, fake news, and whatever else our world was dealing with.

Again, I’m not saying that narrative would actually have overshadowed Nas’ domestic abuse, at least I hope it fucking wouldn’t have—an artist in 2018 shouldn’t be able to just make “important” art and sweep their personal issues under the rug without paying some kind of price. Yet seeing the moral gymnastics performed throughout this era, about art and artists, about the separation between the two, and about the way we all interpret and process celebrity culture, I think that people’s desire to find universal meaning and truth in art has a way of blinding artists’ faults. While the narrative didn’t actually play out, you can certainly see a pathway to its success, and we’ll see it again for some other artist I’m sure. You don’t think Kendrick Lamar’s next album will undoubtedly sweep away his unflinching support of the recently deceased XXXTentacion?

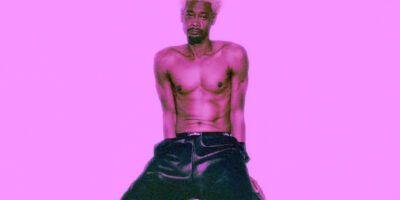

All of this is to say nothing of the album’s tangibles, including a fascinating and sharp supporting cast comprised of Diddy, The-Dream, and 070 Shake, Kanye’s genuinely stellar production (his best next to Pusha-T’s DAYTONA in this run), and a kind of hurried urgency to the whole project, as though if Nas didn’t record it in that moment it would never have ever happened. In a vacuum, Nas made a good album, one that lyrically ranges from some amazing bars to occasionally cringy and eye-rollish, and with beats that are easily his most compelling in years. But with each listen, NASIR crumbles under the weight of its unchecked morality. There are certainly a number of parallels between this and Jay-Z’s 4:44—the shortened length, the departure in musical tone, the singular producer. And yet while 4:44 atones for its creator’s sins, offering vulnerability, tenderness, and apology, NASIR paints a hardened, politicized, and altogether tired rapper, resulting in a kind of tone deaf thud that reveals no other side of Nas. And while nothing he was ever going to release would soften Kelis’ accusations, any value NASIR had cannot overcome his silence.

Comments