There are many reasons why TICKET TO RIDE is considered the quintessential family gateway game. People inherently enjoy how the board fills up with colorful trains, and it’s easy to teach with simple decisions about picking up and playing cards. However, its staying power has much to do with its modularity. You can either play a casual game where players mainly do their own thing, or the game can turn into a mean-spirited knife fight of blocking one another from completing their tickets. As a result, it works equally well with those who want a lighter experience or more intense competitors because each group will get out of it what they put in.

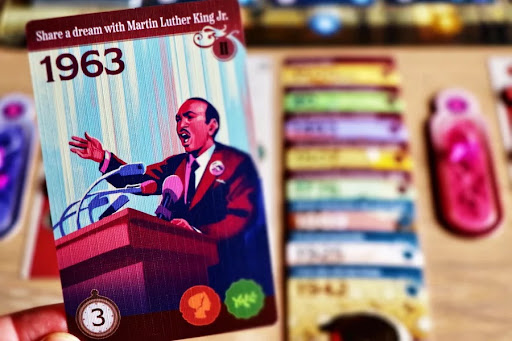

Similarly, TREKKING THROUGH HISTORY can be a fun educational tool or a mentally stimulating game. As a history minor/political science major, discussing the various historical events on the cards you collect throughout the game is fun. Those who go into the game to see Joan of Arc or Martin Luther King Jr. will enjoy that. However, I also desire mechanics, and TREKKING THROUGH HISTORY delivers on the hype. Turns consist of only one decision, yet the ramifications of that decision are engrossing and precisely what I want out of a gateway game like this.

“Take and make” refers to a lighter genre of family games about collecting items, usually through the open drafting of cards or tiles from a shared pool, and using them to construct a building or puzzle for points. At the beginning of each round, players choose an itinerary with different layouts of green, yellow, red, and blue resources gathered by taking cards. Each score in various ways, sometimes necessitating many of one color or sets of all four. Any points not gained by the end of a round are lost since players will turn in their itineraries and take a new one.

TREKKING THROUGH HISTORY evolves on the take and make mechanic by taking advantage of its playmat. Picking a card lets you get the resource on it and the slot it occupies in the row. Instead of cards’ values being static, they’re flexible and ever-changing, but in a foreseeable way. You can see the impact of taking a card on every other player’s choices. Seeing your itinerary at the start of a round and how best to fill it out using a combination of a card’s printed resources and their playmat bonuses is a satisfying puzzle that would be good on its own, but is elevated to greatness through the trek and time track systems.

Each event you take has a date on it, and you can add it to an existing “trek” if it took place after the previous card; if not, you must set aside the current trek and start a new one, scoring points based on the size of each at the game’s conclusion. Unlike the itinerary, these timelines do not reset at the end of rounds, forcing you to pay attention to how each subsequent era has a higher percentage of recent cards and smaller gaps between them. What constitutes a large or small gap will change wildly throughout the game.

Set collection is a component of many games, but many do not punish you like TREKKING. If you build a timeline of one card, it’s worth negative-three points rather than the zero it would typically be. The dilemma of continuing a trek at the cost of fewer resources versus cutting off a set early to maximize the itinerary is already tough. Still, the added threat of negative points makes the calculations even more agonizing.

TREKKING THROUGH HISTORY is elevated into greatness by the final dimension, the time track. Each card in TREKKING has a specific time cost, with players paying that cost by moving their pocket watch on a clock. Whoever is last on the track is next in turn order. Different takes on turn orders are always appealing, whether bidding for a turn order in FIVE TRIBES or getting a bonus based on what position you choose in VITICULTURE. Unlike other games with a time track like NOVA LUNA, a player is done in a round if they equal or pass 12 on the clock. As the pocket watch keeps advancing, the window of opportunity to fill in an itinerary grows smaller and smaller as players must make tough cuts and puzzle out what they can finish in time, with the threat of missing out on points looming large.

Games as heavy as TRAJAN or DARWIN’S JOURNEY and as light as a “roll and write” like SUPER MEGA LUCKY BOX feature combos where players can trigger multiple actions in a row, which is always satisfying. After you pick a card in TREKKING, you can take another turn if you’re last on the track. In addition, the game comes with a crystal resource that allows you to reduce the time you spend taking a card. You can take three or even four cards in a row by smartly spending these crystals, and taking advantage of the cards sliding down and being paired with new resources create some of the most triumphant moments of eureka I’ve experienced in games.

At its core, TREKKING THROUGH HISTORY is another open drafting game about taking a single card per turn. When you take a card, however, you’re thinking of the printed resources, its playmat bonuses, what new combos of the previous two exist, how it fits with your current timeline, whether it’s worth starting a nascent trek if it does not work, how much time it’ll cost you, whether you should spend time crystals to reduce the cost, and whether you can pick multiple cards in a row. These outcomes are easy to understand and digest, yet they synthesize together to make every decision in TREKKING THROUGH HISTORY feel massive in its ramifications. Don’t let the educational flavor text about the Amazons or the Wright Brothers fool you; the mechanics here are robust enough to appeal to those with no interest in the theme.

Comments