I’ll spare his identity, but the greatest film studies professor I’ve ever been taught by once shared the details of his brief stint working as Martin Scorsese’s pseudo-assistant. He wouldn’t answer mail or balance his schedule—it wasn’t that kind of assistant position. No, he was more of a human DVR. Most times, he’d have to set an alarm in the middle of the night to tape a TCM broadcast of a film for Scorsese’s viewing later. Sometimes, he’d have to do that on Thanksgiving or Christmas. Other times, he’d be called in to watch a film with him. Not to discuss it, but to sit and watch it. A few times, he’d be called in to watch a film with him on a national holiday.

He didn’t work for Marty long. I believe some of the more extreme scenarios of my professor’s recollection are embellished for the sake of commanding an attentive classroom, but he was never the type to openly bullshit. His conception of Martin Scorsese deterred many in the room; it mostly endeared me to him more. “Oh goddamn it, I can relate,” I begrudgingly admitted to myself. He’s experienced, but solitude is his default.

In Scorsese’s oeuvre, you’ll observe an interlocking cultural and economic history of the United States where sinners—and a handful of saints—are ultimately cast out of paradises of their partial construction. The search for goodness inside oneself (or, at his most nihilistic, in another) and the aloofness of that search by a God overlooking the panorama of life from a fire escape in the Lower East Side. With a Scorsese picture, you’re never waiting for things to come to a head; the joy is watching the gears grind until someone tells you that, unfortunately, it’s time to get off the ride.

For the sake of this project, I watched all of Martin Scorsese’s features chronologically, and, frankly, when I completed the task on the opening weekend of KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON, I felt this sick compulsion to run it back again from the top. This is a personal, qualitative ranking of Martin Scorsese’s feature-length narrative films. Would he hate that I’m writing about his films this way? Yes. Would he be dismayed that I’m writing about any films this way? Absolutely. Is this the only way to game SEO so I can explore the semiotics and form of the past 60 years of American cinema? Duh.

26. HUGO (2011)

Summer 2007, I was in line to try the pre-release ROCK BAND demo at a Burbank, California Best Buy kiosk. As a GUITAR HERO 2 addict who hooked his whole family, it didn’t take much to convince my parents to spend an afternoon waiting for our turn. But, of course, before any gaming, I had to browse the DVD section first. When it was finally my turn, I set down the day’s selected disc while I failed a drum solo in record time. It was the type of enchanted failure that solidified how I’d be spending my first months back at school, all of winter break, and the remainder of the academic year after that. This game was gonna be fucking sick when and if I hopefully got it for Christmas.

Mind fully stimulated, I set down the drumsticks for the next Tom, Dick, and Harry, making it a few paces before noting my light load and rushing back to recover the film I’d left behind: it was a collector’s edition of TAXI DRIVER. I watched it that night because it made the AFI 100. I was 11-and-a-half entering the 6th grade. So, I fundamentally reject the conceptual premise of HUGO as “a Scorsese that you could show your kids,” a film that’s partly a KUNDUN style cleanse of conscience after a run of particularly bleak endings, but mostly made for Francesca when she was at the same age I was with a RAGING BULL poster on my bedroom wall.

HUGO is the moral majority’s wet dream ideal of educational children’s entertainment: prosaic, Scholastic Book Fair fantasy for parents whose idea of a sweet treat is dark cacao and whole-grain granola served with a piping glass of breast milk. You’ve got the maestro stooping to the lowest lows of making Schoonmaker insert a dog reaction shot to a pratfall. This adaptation of Brian Selznick’s 526-page (?!) picture book is so coddling and condescending to the young freaks who’ve helped keep Scorsese’s position in the zeitgeist as the artist who did more than just make the movies that rewired your circuitry, but implanted a motherboard, period. The sickeningly crisp digital, 3D cinematography is finished with a grayish brown patina, the entire adventure painted with hues of stale pastries left in the shop window. The whole thing arrives in the wake of AVATAR and ALICE IN WONDERLAND, at the end of HARRY POTTER’s run, and at the advent of LIFE OF PI, when audiences were rewarding studios’ entries into a realm of the artificial ultra-real with cartoon images calibrated for malleable children’s minds. The financial benefits of creating worlds in warehouses have defined popular cinema since its inception, but what if those warehouses could downsize to stages dressed in post-production by understaffed, barely paid effects artists? If you’re forced to identify a stretch in history that calibrated the current expectations for the cinematic image (the Netflixification of traditional cinema’s final wave, if you will), look no further.

Asa Butterfield’s voluminous blue peepers peer endlessly, but he’s a rascal lacking streetsmarts or personal drive. When meeting Isabelle (Chloë Grace Moretz), Hugo explains why he’s searching for the activation key for the human-shaped robot in his clock tower refuge—an uncanny curio handed down from his deceased dad—flatly noting “I know it’s silly, but I think it’s going to be a message from my father.” In acknowledging the silliness of his quest, John Logan’s script chooses to not turn Hugo into an obsessive. He’s not much of anything at all, and in the end, HUGO damns Hugo by eschewing him for a final push-in on the mechanical facsimile of a boy while the living-breathing one performs parlor tricks in the corner of the living room. Chloë Grace Moretz really Moretz’ing through a SAFETY LAST! screening, and later soy-facing over D.W. Griffith, Walsh’s THE THIEF OF BAGDAD, and THE GENERAL, can’t carry the dropped weight. HUGO’s overestimation of childlike wonder paves the way for jarring overacting.

The recontextualization of Georges Melies as Walt Disney is a touching tribute to a poorly kept chapter of history, and the recreations of THE KINGDOM OF FAIRIES are wondrous, but is a greenhouse a palace of enchantment to some kid off the street? Are stills in a graduate school textbook able to elicit the grandeur of motion pictures for a couple of tweens? Before 2011, Scorsese never once struck me as an out-of-touch grandfatherly figure, but the movie just has the rank fumes of Russel Buffalino goading Peggy with ice skates and a $100 bill on Christmas. Sacha Baron Cohen’s security officer is the type of antagonist who just makes a movie last longer. He’s not Hugo’s foil, he’s not remotely involved in the central plot, and… Well, now that I mention it, Hugo isn’t even central to the story of HUGO either. Neither is his dad, who just stumbles upon the automaton and, soon after, a convenient gust of blazing death. None of this comes together.

This poor, wounded picture isn’t without its winning charms. There are the cute canines, like the doberman that licks its owner’s oiled leg brace and the painter who buys a puppy to distract his Valentine’s doggy while they share a pot of tea. The retelling of Melies’ history is the good stuff, a signature Scorsese montage through memories of jubilee that—for once—harbors no razor’s edge. In the pursuit of solving the riddle of Papa Georges, HUGO at its best inhabits the childish phantasm of exploring the larger-than-life myths of your parents. Hugo and Isabelle trot through tunnels, stuffy libraries, and inscrutable professors to uncover that Isabelle’s godfather is… A depressed, burnt-out artist who retreated to selling curios because making them had broken his heart. Your parents are just people, but, also, as is HUGO’s most breathtaking fantasy, what if the foundation of the world’s greatest art form were your family’s home movies? Perhaps it isn’t all a dream: in the case of Marty, Bobby, Harvey, Thelma, et al.’s 1970s, the sentiment couldn’t be more applicable. It’s a movie about receiving your due after the worst of times, but as the credits leave you with Shore’s wonderful music—twisty, vast, mysterious—you’re pressed to recall a single moment that deserved it.

25. GANGS OF NEW YORK (2002)

According to Peter Biskind, when poaching Martin Scorsese to produce a film for Miramax, Rick Yorn and Cathy Schulman asked him “If you could do anything, what would it be?” His answer: “I would make GANGS OF NEW YORK, a project that I’ve had for 11 or 12 years.” And with that, so commenced Marty’s bite of the Weinstein apple. More Harvey’s mad pursuit of Best Picture than Scorsese’s new century opus, GANGS OF NEW YORK is stuck in the cyclone of early 2000s prestige austerity, perhaps when movies most directly identified HBO as competition. The whole thing—a Civil War social drama from the circuitous, self-diminishing Northerner perspective—feels like ROME or CARNIVALE when THE SOPRANOS two years prior had cemented one of the best Scorsese homages of all time with its devastating Season Two premiere set to “It Was a Very Good Year.” It’s a hairy, horrid scene when television starts lapping the movies.

In playing with the Weinsteins, Marty wastes a few years making cinema for Academy voters. On paper, it’s absurd that Rob Marshall’s gauche CHICAGO mush beat out a Scorsese historical epic he’d been cooking for decades, but they’re steers from the same stable. The villain literally bashes in the brain of “the minority vote,” and another screams “They don’t speak English in New York anymore?” There’s no political difference between this and THE HELP—I mean, it fucking ends with Bono crooning over the credits, but that’s not before Jim Broadbent’s gleefully opportunistic Boss Tweed (seemingly airdropped in from MOULIN ROUGE!) is awash with shame when blood starts spilling Uptown during the riots and he has his own quote recited to him: “You can always hire one half of the poor to kill the other half.” A movie made for its scope, its clashes, its crowds, opening with a boisterous brawl replete with snapped femurs, torn cheeks, and garden tool incisions; it’s something of a KILL BILL moment watching Scorsese indulge in blockbuster action for the first time in his career and, in proving he can stage bloody mindless entertainment with more precision than any contemporary who’s made stunt choreography their life’s calling, also finds himself content with making this the last time he ever does it.

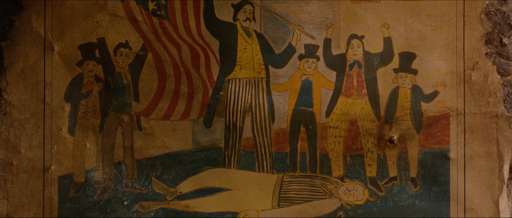

All the more criminal is the Miramax bullshit at existential odds with the intent of the picture. GANGS OF NEW YORK stands in indignant defiance of the scholarly sanitization of American history, a record wiped of its dingleberries and pus-smeared patchwork pantaloons, instead retelling our glorious foundations thru the stench of the oily scalps taking rusted cleavers to room temperature pork. Handling the neighborhood’s meat is a hammy Daniel Day-Lewis playing a nativist Batman villain versus an army of FOBs, Bill the Butcher. Bill’s a messy butcher; he’s also so racist that, in one of the film’s most novel lunacies, he calls the Irish the n-word. You want to talk about Irish-American discrimination? Why does Leo have a southern accent? Day-Lewis is the haughty centerpiece of a film heightened past the point of safe consumption, the entire debacle tainted with FELLOWSHIP OF THE RING color grading and aspirations of Sideshow Collectibles figurines created after its characters. Everything in the catacombs feels more like schmoozing with the orcs than exploring an underground urban transit network (Howard Shore’s orchestral scraps from Jackson’s trilogy don’t help). Framed and designed with an eye for overwrought, pompous flash, the film looks as though how most graphic novels were being adapted for the screen: gothic fantasy riding the line of staunchly literalist authenticity. A rare human moment that clicks the movie into gear comes when Amsterdam and Jenny kiss each other’s scars, learning one another through necklaces and laces. It’s passion at its most histrionic, but it’s the first time the two work. Leo and Diaz can’t sell any of it, and even Stephen Graham is more befitting Tony Pro than an Irishman. It’s miserably miscast, the film’s sweeping urban vistas bringing greater attention to the backlot quality of the artifice’s construction, a testament to Bill’s “spectacle of fearsome acts.”

The rote revenge tale is a means to culminate with the Draft Riots overshadowing the central plot’s gang war, sidelined by this orderless class uprising turned senseless lynch mob. The Irish resentment towards the empowered draft dodgers mutates into a hatred for the peoples they thought the war was fought over, leading to Union boys gunning down walls of Northerners. Scores of New Yorkers die by the hands of the state: the avenues turn to literal red rivers. GANGS OF NEW YORK sees Scorsese settling his lifelong aspirations after the decade that took his parents, but the wheels fall off the wagon within minutes. Why are we here? What material function does crime serve in the immigrant dumping grounds of New York City, and where is the civic solidarity? What propels the human soul in the late 19th century beyond survival? Is it that everyone has their personal revenge fantasy to be motivated by? And yet, the picture must be enveloped in its own rectum for that gorgeous ending of an overgrown cemetery of memory to land with the contrition it aims for; all this fuss, and then it was all struck from the historical record. 160 dire minutes in exchange for a stunning concluding seven. After three winning decades of films that thematically and formally sliced against the grain of American fare, somehow it’s the longed-after definitive history of the most lauded city in the world that ends up feeling more in line with consumer wants than your Tom Cruise vehicle. The failures of GANGS OF NEW YORK lie at the feet of Harvey Scissorhands, but it’s a film that tanks the filmmaker’s batting average significantly enough that, 20 years later, people feel comfortable comparing BABYLON to him. It’s fair—a touch indelicate, but it’s fair.

24. KUNDUN (1997)

Oh how heavy is the 6000-serf-owning head that wears the wait-I-didn’t-know-that-all-of-these-guys-were-serfs-hold-on-are-we-bad-guys crown. Forever fated to being a punchline on THE SOPRANOS, there’s a touch more credit we should allot to KUNDUN, the most obvious outlier in the entire Scorsese catalogue—but only just a touch. It’s a preposterous, but logical CASINO follow-up: a topical tale of peace that atones for the contemporary decade written by the E.T. THE EXTRA TERRESTRIAL scribe and bankrolled with hefty Disney checks. A job’s a job! His dastardly tastes can’t help but spring out for the depictions of Mao’s systemic violence. KUNDUN’s most memorable edit is a cutaway from a conversation about a Tibetan child forced to squeeze the trigger that executes his parents to Schoonmaker’s ratatat of overkill blood splatter and the aforementioned kid’s operatic wailing. An entire set piece condensed into three seconds, if even that. The film desperately maximizes its tempo whenever it can: even patient cranes over a landscape will dissolve to cut down a few seconds of movement. Otherwise, it’s a traditional biopic about the 14th Dalai Lama that’s part THE LAST EMPEROR plagiarism and, in its apex, a guilt-ridden reflection of perfection that’s refused nuanced dissections of his creed nor genuine communal fealty to Buddhist teachings, all squeezing the Dalai Lama to a point of no return until he is forced to take refuge in India. It’s that slow Chinese ouster from Tibet that sings—the death of the past that “will not be seen again” as depicted through the quandary of where personal blame should be placed, if at all. The presence of God is qualified by whether His disciples’ goals align with His message. However, in its frequent lulls, KUNDUN is a movie made for Frasier Crane.

In its first act, the search for the 14th Dalai Lama ends with a baby boy, Kundun, whose broader adolescent education comes from newsreels and footage of feudal epics. He seems like a chill little dude despite the thousands of slaves (of whom Melissa Mathison pays no mind), but he tellingly looks back on those who’ve helped him as lambs for slaughter. Are they sacrificing for you or for Buddha? Little can prove more to us that the entirety of KUNDUN is a professional wash than SILENCE so explicitly asking these same questions nearly 20 years later in an unbroken treatise tethered to no living figure with whom you must seek approval. Even HUGO returns to the childish wonderment of hand-cranking a Melies motion picture. The problem is that there’s no single great performance to tap into; Mao sounds like a Muppet, and Tenzin Thuthob Tsarong can’t command a single moment away from the exciting Godfrey Reggio-type visual interludes. It’s Marty jogging about Morocco with a Deakins-shaped butterfly net trying to catch a fluttering emotion in the candles, ornaments, and faces he finds. One of the silver linings of Disney limiting the home video release and cultural memory of KUNDUN to cave to the Chinese government’s complaints (I’m moderately pro-China, but Jesus Christ can those administrative motherfuckers shift their whining focus into matters of zero importance like few others) is that it never seemed like Scorsese was entirely invested in the first place. For Michael Eisener, there’s such a bizarre cowardice in making a prestige Dalai Lama spectacle then immediately burying it just one year later—Eisner called it a “stupid mistake” even. Actually, you should read more of Michael Eisener’s comments to see the extent to which fabled studio heads do not have their artists’ backs: “The bad news is that the film was made; the good news is that nobody watched it. Here I want to apologize, and in the future we should prevent this sort of thing, which insults our friends, from happening.”

KUNDUN pares down the historical complexities to craft a simplified story of compromised boyhood and the difficulty of non-violent maturation. It’s the baby-girl-ification of the Lama, and whatever he isn’t immediately aware of applies to the viewer, as well. This is not a historian’s depiction of history. Over-simplification works for crooks because there’s an inherent patina of innocence and empathy that makes more nuanced “villains” out of them—it’s good drama—but with an already deified figure, you’re throwing a tennis ball against the wall. The cherry on top is Phillip Glass’ hilarious score: sometimes it’s the most transcendent composing, then interspersed is a Yamaha keyboard with the “Horns” sound effect leading the hook. David Edelstein’s Slate pan puts it more succinctly than I ever could, detailing Glass’ score, and thus the KUNDUN experience, as inducing “a kind of alert detachment, so that you’re neither especially interested nor especially bored.”

23. BOXCAR BERTHA (1972)

The opening title card of BOXCAR BERTHA proselytizes its basis in “true experiences” before hard cutting to a close-up of cinema’s most classical harbinger of truth: Barbara Hershey’s wide-open peepers. Marty’s lens ensures the impact of her image, be they refracted off sunlit car doors or published in newspapers as her thieving scoundrel character, the titular Boxcar Bertha, hops from one train robbery to the next in Great Depression America. Reading the headlines isn’t the celebration her band of outlaws hoped for, the whole room surrounding the daily rag reckoning with who they are (smooth-talking Rake painted as the coward of the bunch), what they’ve done (Bertha described as the common whore and murderer), and who’ve they become (David Carradine’s Big Bill morphing from socialist rabble rouser into materialist mugger). One in a celebrated lineage of the ‘70s nostalgia for the decrepitness of the 1930s, a mid-20s Scorsese was tasked by Roger Corman to bring home a follow-up to BLOODY MAMA (a Shelley Winters period exploitation vehicle) as his first big break. As Bertha coasts from town to town, Scorsese costumes every nook and cranny with country boys who look like con men from Queens, LES Puerto Ricans, or Diamond District Jews. Personally? J’adore, especially if it means I get to see Victor Argo brood about, but we’re under the wing of a filmmaker who’s never not under the wing of his hometown.

Bernie Casey’s final bloodbath as reformed criminal Von Morton with a kickback-less Trench Gun sees railroad goons strewn across the screen taking cannonballs to the stomach like Frank fucking Richards, but BOXCAR BERTHA still prioritizes sneaking in a moment where one of the victims is stunned by the blood splatter of his friend right before biting a bullet himself. Even in his creative nascence, and even in gleeful massacre, Scorsese’s insistence on building story through emotional texture busts through. Its final image—a crucified Commie riding into the afterlife on a steel locomotive as a weeping Bertha gives chase—is brutal. And yet, in writing about it days after viewing, I’m struggling to remember anything about it without peering at the thoughts in my notebook. When compared to the defining masterpieces of 20th century cinema, it’s easy to jilt BOXCAR BERTHA like Cassavetes had to Marty’s face on that fated day in his office where he called it a piece-of-shit exploitation flick (an interaction that spurned the rapid rewriting, funding, and production of MEAN STREETS), but if the mission was to produce a mean, titillating programmer for the blood-hungry Bolsheviks, then consider me satiated.

22. WHO’S THAT KNOCKING AT MY DOOR? (1967)

If WHO’S THAT KNOCKING AT MY DOOR? marks Scorsese’s explosive entry to his own canon, then consider Thelma Schoonmaker’s work in the editing bay a nuclear blast. Ray Barretto’s “El Watsusi” blasts as a handgun gets passed around the little boy rager, the barely pubescent Italian-Americans aiming at each other, grasping the barrel, and huddling atop one another playing hide and seek from the one who’s strapped with it. The subtlety of a mid-20s filmmaker. We cut from the gun misfiring to an exploding bottle, to a visual ricochet across the room, then to an insert of a RIO BRAVO poster, and then to the exterior of a theater where J.R. and The Girl are exiting a screening of the Howard Hawks western. They gently enter a conversation of their sexual proclivities, and the differences between girls and “broads,” leading to an imagined sense-memory of Keitel fucking a bounty of broads to The Doors on a bed frame in the middle of a vacant loft—Francis takes this song, “The End,” 11 years later, the same length between WHO’S THAT KNOCKING AT MY DOOR? and THE SEARCHERS. The scene goes on to capitalize on the full value of the licensing fee. The camera swirls, the women come and go, Keitel never surrenders. After Jim Morrison conducts the psychedelic breakdown, we cut back to the convo on the sidewalk about “broads.” It’s filthy, aggressive, mad-dash mid-century filmmaking innovation of the highest order. It is also barely held together by bubblegum, snot, and sweat.

21. AFTER HOURS (1985)

Awash in critical reappraisal, AFTER HOURS has effectively made the turn from cult classic to bona fide essential in the Scorsese catalog, and I couldn’t be happier for it. The rare spotlight for the monobrowed comedic fashions of Griffin Dunne, Scorsese retreats to a dirt cheap indie comedy after going 0-3 from 1977 to 1983. As tumultuous as HEAVEN’S GATE’s burst New Hollywood bubble was, God, what a utopian state of the industry where the director of TAXI DRIVER could just shack up in refuge with a bunch of 20-something independent filmmakers before tackling a Paul Newman tentpole comeback. It’s a bonkers extended cut of the “So, no head?” Vine, a rendezvous with manic dirty blond-dyed dream pussy turned into an ANIMANIACS-tinged catastrophe of pitchfork mobs, sleeping pill overdoses, and papier-mâché mummification. Marty’s doing tricks on it just for the love of the game: the POV of the falling keyring, the boosted frame rate of the speeding cab, the first-person key entry are all completely unnecessary thrills that get you going all the same.

AFTER HOURS makes the bold choice of playing down the blatant yuppy critique by making Paul realistically boring. While carrying on in ill-fitting blazers and residing in the most sterile professional apartment that pay stubs can afford, he’s not a careerist who has convinced himself of the artful necessity of word processing, nor is he a shill for the corporation he inundates new recruits for—when training a rookie staffer, the new guy tries breaking the ice with Paul by excitedly sharing that he’s taken this numbing filing gig so he can open a magazine for intellectuals, to which a disinterested Dunne hilariously lets trail off into silence. It isn’t that he’s offended that his muse has no respect for his career, it’s more that this scrub is likely the 64th temp he’s trained who doesn’t want the job. He gets it, he’s heard this diatribe, so let’s just acknowledge that our dreams are collectively squashed and move on from this stargazing so we can clock out before killing ourselves. We live in a city where fare-busting gets your balls crushed over 57 cents, where leaving the house with only a loose $20 bill will doom you, and where I can’t even fuck some broad I met at the coffee shop because she killed the mood by telling me that she was raped in the bedroom I am currently trying to fuck her in. I just want to go home, and I just want to be able to wake up so I can go to work, and then go back home again. It’s less dramatically compelling, but bitterly funnier that Paul is so crushingly normal, because it shows what “normal” has become in the modern American hellscape. It’s a very fun decision, but Griffin Dunne isn’t perfect for the role; I think of Paul’s flat delivery of “I’m probably to blame for that,” and, as much as I appreciate Dunne, he hasn’t got the juice to make the nerves of the piece sing.

What is comedy but a Christ-like progression of trials for the most pathetic dummy alive? Just make it hurt and you’re on the right track. Does it really surprise anyone that the Catholic asthmatic outsider rides for PEARL and Ari Aster? AFTER HOURS finishes on a superlative zip around Paul’s office to Mozart, an incredibly compassionless fuck-you to its protagonist and to those viewers who hoped he’d ever return home. Does he deserve this imprisonment by the ruling gates of capital? Paul maintains his composure throughout the night, but the funniest cracks make you wonder if the PCP is taking the lead or just revealing his inner morals. How else do you explain the handwritten “Dead Person” sign he tapes on a cold Marcy’s door? Or the outright refusal to ditch all of Soho hunting him down by just sucking up and embarking on the two-hour walk home? Can a man both suck and also not be sucked up by a lynch mob? Sure, but that’s not entertainment.

Ultimately, AFTER HOURS is an act of personal therapy for Scorsese—though more akin to stretching his hamstrings than actually pushing heavy weight. It’s funny, it’s entertaining, but it’s not very interesting; notably flawed is the lazy depiction of Soho, one of the few great missed opportunities in the director’s career. When ROBOCOP can muster a more genuine portrayal of the punk scene than the director of MEAN STREETS, I can’t help but be disappointed by the turgid studio comedy approach. Okay, there: I don’t understand the effusive AFTER HOURS hype. It was beneath him and it still feels beneath him, too transparent in its function of furthering everyone’s career to stand as a festering manifesto begging to be unleashed. Yes, I will be rewatching it until it hopefully one day changes my mind.

20. SILENCE (2016)

The adult thing to do is pretend that I’m not bored out of my mind by SILENCE because Sean Fennessey told me that it’s actually a secret masterpiece, but the mature thing to do is admit that the spiritual interests of SILENCE have yet to align with mine. Transfixing is the film’s focus on religions whose basis is in the physical and spiritual values of secular items. Is this essentially a movie about a stuff-loving guy in conflict with the anti-materialism his ideology shuns? Kind of! An accentually challenged Andrew Garfield as the Portuguese Padre Rodrigues arrives in a Japanese village with a rosary and a few hastily made straw crosses, but the inhabitants (all Christians in hiding) treat them as second coming of Christ. In these objects, their faith in God is strengthened. “They are desperate for tangible signs of faith” perhaps more faithful to these objects than faith itself. It’s not Christ’s face that Rodrigues sees in the pond’s reflection, it’s Goya’s Christ—and if it is a divine signal, then Jesus just mobilized The Inquisitor’s troops onto him with it. What commences is an hour of Garfield staring at the theatrical torture of his disciples.

If the Portuguese priest does not apostatize, the Japanese caregivers will be executed one by one. They are. Even the fugitive Padres (another played by Adam Driver at his gangliest) become physical objects themselves, and henceforth progenitors of death in their name and presence. As families are forced to watch one another burn alive at the stake for refuting Buddhism, God allows it. Rodrigues—traveling from St. Paul’s College in Macau—is in awe of the unprecedented love the persecuted Japanese have for the Lord, and slowly grows aghast at the lack of a divine intervention in their cleansing. Shinya Tsukamoto as the priests’ interpreter shares that “my love in God is strong. Could that be the same as faith?” Who knows!

I observe the Japanese Christians and can’t think of anything beyond wanting them to step on the fucking tablet already, to stop being ridiculous about this piece of metal and practice their virtuous right to lie to the government. Taking place at a peculiar point in history when Christianity is both a subversive school of thought and the basis of empires, SILENCE isn’t entirely concerned with the historical sociopolitical chicaneries of Christian conversion. From a wary Japan’s perspective, having seen Spain’s slave state in the Philippines after their population was largely converted, purging 300,000 Japanese Christians is a measure to diffuse European influence. It’s barbaric, but understandable. A Christian Japan is, in fact, a selfish dream by design, and rather than embark in international war, the empire battened down its hatches. The 17th century separation of internal communications leaves Padre Rodrigues blissfully ignorant; he truly believes he is a savior, not knowing the role that saviors play in international conquest. SILENCE is a film that rewards knowledge of its context, but it is not remotely a picture about that guilt. Its preferred flavor of guilt is best showcased in a moment when Rodrigues is let down for the umpteenth time by the rapscallion Kichijiro, a consummate coward who will rat out his fellow brother for a scattering of coin (think a more feral incarnation of Johnny Boy). “Father, how could Jesus love a wretch like this?” Rodrigues screeches, but he quickly relents. To be capable of seeing this amount evil in man, is he even worthy of Jesus? What does this level of judgment say about his own character? Therein lies perhaps the ultimate question of Martin Scorsese’s catalog, and maybe the central question of his being. That’s all I’ve got for now. Seven years later, after many more films seen and a few more books read, I’ve more to bring to SILENCE, and until the day I’ve assembled more, I await its voice in the silence.

19. NEW YORK, NEW YORK (1977)

Even if you’re looking for it, it’s impossible to pinpoint the chaos of NEW YORK, NEW YORK’s creation. It may very well be the most muscular cinematic cataclysm ever coughed out by a tortured cast and crew. For a three-hour romantic drama about love as an addiction by an artist in the deepest phase of his drug use, I couldn’t imagine it being produced under any other conditions. Francine manages to kick her habit. Jimmy’s cut off from it and slinks off into the credits, leaving the movie in the dust to refocus on green pastures and healthier ideations of life… Just like Scorsese with NEW YORK, NEW YORK, withdrawing to the safety of prior risks in his big-budget breakthrough. Ever present is the pastiche from the opening credits of ALICE DOESN’T LIVE HERE ANYMORE, directly emulating Vincente Minnelli’s technicolor musicals, and Robert De Niro rolling up all of the MEAN STREETS boys into a single jawbreaker and sucking on it ‘til drool runs down his chin.

De Niro is a master of the unwanted goon, sometimes affectionate and more often repugnant; his signature wonder is in how he ensures that his scene partner is always cutting the wrong wire. A reactive, predatory force of nature who hunts in service of the scene and never his own vanity, there’s no one better than Bobby to depict the types of men who ritualistically humiliate waiters like it’s a divine Aztec sacrifice. Jimmy, an up-and-coming sax player with zero charisma to his name, is a guy who would try to convince you he was a potted plant if it meant sucking on your neck. His stamina wears down Francine, played by a frustratingly reserved Liza Minnelli, who spends most of the picture suffering Jimmy’s wrath. A reactive and impulsive beast, too. Jimmy reads Francine’s poems in the middle of the night and dresses her immediately so they can drive to an undisclosed location. It turns out to be a rural chapel, where he intends to marry her during the graveyard shift. When she expresses disappointment over the venue and circumstances, he lays down behind the parked cab that drove them there. When they first met, there was zero spark, just Jimmy persistently negging Franny. And it worked! Pestering the austerity of others ‘til his approach forcibly bleeds through,That’s the early Marty way!

Deep sea diving without an oxygen tank, Martin Scorsese attempts to transpose his improvisatory methodology to the backlot extravaganzas of yesteryear that his pioneered film movement helped bury, but the compounding degrees of hand-biting retaliate against the film itself. The sets are artificial in a way that elicits more memories of SANFORD AND SON than SCARLET STREET, just none of this really works. It takes two full hours for Francine to yell back at Jimmy, and when she does, he promptly evacuates his marriage and the picture. Almost immediately, the movie jumpstarts anew with electric vigor, Minnelli afforded her very own FUNNY GIRL in a phantasmagoric assembly of fantasies. Unfortunately, the movie’s unending insufferableness is essential for the cathartic release of the final, euphoric 40 minutes. When we get to Liza singing the titular track, there’s a close-up push-in on her above the crowd that would be the greatest shot of any other director’s career—this Italian motherfucker cannot miss if his life depended on it. NEW YORK, NEW YORK may last a lumbering eternity, but it creates the great American ballad and then subjugates Scorsese to maybe the worst three consecutive years imaginable. ‘70s New Hollywood was horrifying, such grievous labor abuses disguised as maverick filmmaking, and if you bat anything less than a grand slam then you are sentenced to the professional gulag. Now, if you make one of the most reviled films of the decade, you’re punished with a showrunner gig. And while all this is happening, Marty Scorsese’s professional rock is Steven fucking Prince. Yeah, I’d collapse from pneumonia too.

18. SHUTTER ISLAND (2010)

Like Howard Hughes emerging from THE AVIATOR’s introductory steam as a nude summer child, a seasick Leo ambles in from a ferry out of the fog. Not seasick, gumshoe detective Teddy Daniels notes, but overwhelmed by “a lotta water.” The stakes of CAPE FEAR return upon the call of “Storm’s coming!” We drive headfirst into the Ashecliffe Hospital for the Criminally Insane, Penderecki’s “Symphony No. 3: Passacaglia” shattering your enamel. We’re in sick-nasty genre territory, Val Lewton-core iconography of rats, rain, witchy women, and still corridors. Let’s get it out of the way: this was my first time rewatching SHUTTER ISLAND, a film that exists in a completely foreign narrative dimension when knowing the (in hindsight, intensely forecasted) twist. Teddy Daniels is, would you believe it, an inmate at the very asylum he’s investigating! “Teddy Daniels” isn’t even his name! The arsonist that annihilated his wife? That’s a projection of himself! Turns out he killed his wife after she drowned all three of his kids! Gotcha!

From THE LAST TEMPTATION OF CHRIST to THE IRISHMAN, many Scorseses barrel towards inevitable conclusions, but SHUTTER ISLAND most directly concerns resolutions and answers. By 2010, it’s a little late to be doing his KISS THE GIRLS, and a confusing choice after the freedom of Oscar glory—Scorsese’s right, he really should’ve prioritized SILENCE with the momentum afforded by THE DEPARTED. The horror pivot will always be there to bail you out (of, say, a cash-hemorrhaging SILENCE). It’s a very fine mystery, but a mystery streamlined past its prickliest reprobations. Set aside are the spiritual conflicts of the doctors playing God with their patients, shunning the BRINGING OUT THE DEAD dilemma to plot onward for the big twist. It’s all dashing towards a great unveiling of the ultimate gimmick. Fortunately, it’s one of the most skillful gimmick movies ever made, that very plotting inherent to the rehabilitative philosophy of the film and its experimental brain conditioning.

Scored to Mahler and recalled to SHAME’s Max Von Sydow (enjoying himself too much as a Nazi-defecting doctor), we witness the liberation of Dachau by Teddy’s battalion. The German officers are herded to a barbed wire fence, and a nervous gunshot triggers an all-out mass execution; Robert Richardson’s camera dollies down a firing lane of piling Nazis. There is no justice felt, just a fostered abhorrence to the slaughter. God’s gift: the violence. A matinee thriller about a mind at battle with conquering violence, SHUTTER ISLAND asks which multiple murders broke this guy’s brain the most. Leo is acting so hard that you totally get the full impact of the afternoons his mental illness went Super Saiyan. He can’t take living as a monster even if he’s positioned as the hero in both scenarios. By doctor’s orders, “Teddy” is run through a genre exercise to evaluate his guilt and rectify his schizophrenic violence; however, it’s still the early ‘50s, so if the ruse doesn’t fully cure him, then to the lobotomy station he goes. The doctors of Shutter Island are hopeful for a revelation in the enveloping fantasy. In some medical circles, they call this tactic “RAGING BULL-ing.”

17. THE AGE OF INNOCENCE (1993)

The 1870s bore witness to the Ethiopian-Egyptian War, Romania and Bulgaria achieving independence from the Ottoman Empire, and Sioux resistance battalions warding off the United States Cavalry, and here I am watching some farty chumps in The Gilded Age daydream about necking blondes in vacation houses—these white lives do not matter to me. For the longest time, and for perhaps unfair reasons, I have maintained a consistent bias against THE AGE OF INNOCENCE. Unless they’re stabbing each other or getting slaughtered, I have little-to-no patience for Reconstruction-era nobility. The Romanticism movement was an aggressive, centuries-long act of class terrorism via the arts, and I’d be totally okay striking Edith Wharton’s novel and all of its kin from the cultural record.

That being said, this crucial rewatch opened itself up to me: I think both Wharton and Scorsese agree with me. A secluded world of riches only a few square miles away from the blistered alleyways of material inequality, where gossip is gospel. On one hand, THE AGE OF INNOCENCE is an intentional grotesquery of its aesthetics: recall the elegant tour of Mrs. Mingott’s hung art collection, landscapes and social scenes ending on a painting of Natives tomahawking a cowering white damsel. The oppressors will constantly find ways to portray themselves as victims. On another hand, that gossip cannot be glazed over, otherwise you’re fucked out of the movie you’ve settled in for. You must engage as a viewer with this trite, meaningless slander as though it were a matter of life and death, you must find these meaningless trifles more impactful than Christian doctrine. If you don’t, it’s a very pretty screensaver.

It’s tough. THE AGE OF INNOCENCE hates THE AGE OF INNOCENCE like I do. Ultimately a tale of two lovers sorely disappointed by the American vision, its staidness and replications. The descriptive prose fades in over recitations of social ritual. Pallid salmon, thrice-roasted beef, roughly chopped cigars as symbols of opulence that are both comforting and enclosing, the feasts persistent and intrusive, surrounding adornments stifling the echoes of the high ceilings but entirely impersonal homes. The clue that these meals aren’t meant to whet our appetites is in recalling the portraiture overheads of Travis Bickle’s Alka-Seltzer and slop. Scorsese’s runtimes are so precise, the repetitions of time spent pummeling both you and the characters with similar force. There must be more for my nose, eyes, fingers, and tongue than these displays of unquestioned status. High society is built so precariously that its harmony could be shattered with a whisper, there’s no way we’re the apex predators. If you give in, it’s a respectable drama. Daniel Day-Lewis cannot play indifference, it isn’t in his nature. The passion in Newland’s perennially wet eyes renders his narration into a teeth-gnashing denial. Every claim of his detachment from Lady Olenska is immediately countered by his bloodless face. The death of the soul is lit only by a setting sun. Oh, to suckle on Michelle Pfeiffer’s wrist, to project your personal angst onto a forbidden lover who’s doing the very same to you. Reading about Japan because it’s a different country, and courting Olenska because she’s practically Japan compared to NYC regality. It’s insulated nonsense, but, fuck, is it hot.

16. THE AVIATOR (2004)

For the days I crave the stylings of Steven Spielberg, I’ve never thought to pop on THE WOLF OF WALL STREET. For longer than is appropriate, studios have interchangeably regarded Marty and Spielberg as hopefuls for developing projects, but it’s never been more unspeakably clear why than with THE AVIATOR. A retelling of Howard Hughes’ few glorious decades in the sweeping delirium of mechanical innovation, the film’s pursuits of grandeur are rankled by its subject’s ornery steadfastness. The film’s not a great fit for Steven, because this is one of the few biopics where the smarmy Louis B. Mayer tells Howard he’ll never make it in this town and is proven resoundingly correct. Purchasing airplanes like candy bars at the checkout line, he’s no underdog. Scorsese’s for-hire exploration of “the eccentric genius” as an aspirational concept and flesh-and-blood debacle is another installment in his critique of the American charlatan, in this case the billionaire CEO whores of capital ready to guzzle senatorial cock while they press “Add to Cart” with Daddy’s overseas drill bit fortunes. In some ways it’s an exhaustive diagnosis of an infamous recluse, but in other ways, Scorsese’s already ambling vision is lost in the auto-pilot of studio filmmaking.

The self-stimulating technical prowess of emulating two-tone technicolor is the work of a master fetishist (the hand-painted greens of a Woodland Hills golf course is certainly a period-accurate affront to the eyes), but it’s a peculiar expressionistic endeavor when placed next to the CGI that aims to realistically portray these turn-of-the-century iron eagles. To follow the philosophy to its logical conclusion, shouldn’t Hughes and Hepburn’s terribly tender flight over Los Angeles be shot with a rear-projection of the Hollywood horizon? Marty’s really having fun with period specifics throughout (Howard’s long box of vanilla ice cream will forever scream to me), but those colors, my God; the pursuit of verisimilitude bumps against blockbuster ambitions in every single second of the picture. It’s a tough beat, the late-90s into the 2000s seeing Scorsese’s “80s-90s Spielberg” arc of chasing institutional legitimacy come to a head. Still, as fraught as they were, the 2000s are a bygone era when auteurs would sneak their signatures into a massive commercial biopic and not just toss dutch angles into a DOCTOR STRANGE. In another director’s run, THE AVIATOR would be their tour de force. In Martin Scorsese’s, it’s a formidable work.

15. RAGING BULL (1980)

There’s a bonding structural element that joins those who despise or cherish RAGING BULL: Scorsese didn’t want to make it. A plodding, desolate portrait of an irredeemable beast told in a black box theater put on by a filmmaker who has no respect for the sport of boxing; RAGING BULL is garbage because obviously Scorsese didn’t want to make it. Brought to him on a hospital bed by his devoted muse, it’s an achingly personal atonement sheathed in the boiled skin of another goon’s spotlight. Through a thorough examination of the constitutional, biological violence of men in idealist Americana, it’s the picture that resurrected a shattered spirit. I remain unsure if Marty ever really finds out what this is about, focused instead on using a schnook meathead’s spotlight for his own rebirth.

Jake La Motta prances in the fog of a smokey ring to an Intermezzo from CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA, instantly succeeding on NEW YORK, NEW YORK’s original mission of rejuvenating the golden age. The movie looks chiseled from stone, to the point where there’s a DEAD MEN DON’T WEAR PLAID quality to De Niro and Pesci terrorizing every mobster and woman they meet through the inky ‘40s. History retold with accurate vulgarity so that our vile behaviors can’t be blamed on modernity alone, a tale told in mutterings, with drama generated from pitch shifts in the indecipherable grunts. Jake and Salvy’s impromptu meeting at the Copacabana is like looking in on an ape exhibit. Cramped apartments, arena dressing rooms indistinguishable from police holding tanks, and boxing rings located in the same nebulous purgatory as the top floor of TWIN PEAKS’ convenience store: there’s an unrealism only found in the cinema that RAGING BULL utilizes to capitulate the rawest interpersonal nerves, De Niro adapting the anxious aggressions of Seymour Cassel in Cassavetes’ most gut-wrenching works with his own morphing physique. Travis Bickle’s sick thoughts transferred into the brutish, mundane activity of an American father.

This is a tough watch. When we’re first privy to Jake LaMotta’s domestic life wife kicking drawers in the bedroom, giggling as he mutters “What’d I do?,” her displeasure is so inconceivable to him that it becomes an absurd lark. Is Jake ever really lost in his rage, or is he an addict to the adrenaline? Jake has a total awareness of the objective scenario he’s in, yet he keeps jabbing at her, like a prize fight. What does Pesci punching him with a ring even prove? The film’s most bristled moments are those that afford acceptances of Jake’s tender mercies. Jake and Vicky’s pre-fight foreplay goes on forever, the sole moment of unbridled eroticism. She kisses his chest, then his stomach, and then his waist, until he springs up to the bathroom to ice his erection so he doesn’t blow it before a fight. She just kisses his neck from behind, framed between images of Christ and Mary on their bedroom walls. To afford The Devil his humanity is to witness what he’s capable of forsaking for his own behalf. One can only hope that creep never got a good night’s rest after watching his own movie.

- THE LAST TEMPTATION OF CHRIST (1988)

I know, I know I’ve let you down

I’ve been a fool to myself

I thought that I could live for no one else

But now, through all the hurt and pain

It’s time for me to respect

The ones you love mean more than anything

So with sadness in my heart

I feel the best thing I could do

Is end it all and leave forever

What’s done is done, it feels so bad

What once was happy now is sad

I’ll never love again, my world is ending

I wish that I could turn back time

‘Cause now the guilt is all mine

Can’t live without the trust from those you love

I know we can’t forget the past

You can’t forget love and pride

Because of that, it’s killing me inside

It all returns to nothing, it all comes

Tumbling down, tumbling down tumbling down

It all returns to nothing, I just keep

Letting me down, letting me down, letting me down

Being Mexican-American means that I am, by doctrine, a defunct Catholic who has—and I’m deeply apologetic for what I’m about to admit—had their spirituality reawakened more by THE END OF EVANGELION than any of the dozens of masses my abuelita forced me to attend. A few weeks ago, I was listening to “It Is Accomplished” on the freeway in the dead heat of the afternoon and I spontaneously burst into sobs. Not to give into the hype (of Scorsese’s landmark masterpiece, not the Holy Lord, come on now), but maybe there’s something there! Christ’s death is a victory! It is not finished, it is accomplished! Congratulations! Get on the crucifix, Shinji!

13. THE COLOR OF MONEY (1986)

When in doubt, Martin Scorsese will just make a movie about himself. When tackling a for-hire subject he’s little interest in (Howard Hughes’ upward failures, technical boxing, any part of billiards), he dilutes them into their most attractive and primal aggressions (directors as dictators, jabs as humbling mortar blasts, and—in perhaps the most animalistic portrayal in the director’s oeuvre—stripes and solids as colliding atoms). Every insert of rocketing billiard balls runs counter to how anyone who’s played a midnight match knows how the game feels, but THE COLOR OF MONEY isn’t about hobbyists. It isn’t even about athletes. Its opening moments hover over a cigarette left to flame out, Robbie’s semi-Broadway, partway electric bass country funk gliding us into an autobiographical treatise on pacing yourself. THE COLOR OF MONEY is less about hustling pool sharks and more about choosing when to present as best and when to assume the student position. Do you showboat for an instant $150 payout, or do you respect the art and savor the work by stretching out the game to $5? Replete with the bored, toe-tapping, digit-spinner approach to adapting a for-hire screenplay, Eddie’s appeal for an honest game seems to be coming from the artist to himself: “I just want your best game, I think the money’s what’s been throwing you off.” Folks, it’s literally just a movie about how Marty makes movies, an almost Randian, objectivist text on peacocking and stature, and I say “almost” because it’s mostly a movie about staring at Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio.

Billed as a Newman and Cruise double-header, the real thrill is watching the two bounce off Mastrantonio—they’re perfectly fine with each other, but it’s two suns (Eddie and Vincent) glowing off one another. It’s a blinding light, Vince adoring the mentorship but strained by the tight leash even after so many games together. But with her, it’s two lions negging and nipping their tamer. Eddie handles Vincent’s intimates through Carmen, for one because he’s more interested in her dimensionality, but by casting her as his manager, it lets him work his charm as non-gayly as possible: second to SLAP SHOT, it’s the best movie George Roy Hill ever directly or indirectly conceived, Y TU MAMÁ TAMBÍEN in the forgotten halls of barfly glory. There’s a confident bravado critical for a vanity project you’ve been brought on to realize for the producing star, but it’s finally a movie as nervy as Scorsese himself, on a constant swivel like him, with its eyes darting back and forth and up and down like his. When you see Newman in aviators consuming a third of the frame, while Cruise and Mastrantonio fill the other two, you know in your bones that you’re just watching a training session for GOODFELLAS and CASINO. God bless the opportunity to be present for the rehearsals.

12. ALICE DOESN’T LIVE HERE ANYMORE (1974)

The women of Scorsese’s cinema have been the source of bad faith scorn for half a century, and though reducing ALICE DOESN’T LIVE HERE ANYMORE to a “see, this one stars a broad” riposte, is… Well, this is the one that stars a broad! Ellen Burstyn’s Alice is a manic oddball: crass, judgmental, impulsive, cripplingly self-aware, and drunkly romantic when she’s not narrowly pragmatic. Life hits her hard, but she’s hitting back with such force that even her dearest associates are fielding the blowback. She’s a singer but not a star. She’s got an honest voice that can bring a bar to a whisper, but the whole act—from the numbers and attire to the sheer expectation of bars still hiring resident pianists— is a relic of 1962. It’s her only reference for functional adult living since shacking up with a truck driver who could kiss real good. She was molded to live with men, and that’s a tough regiment to break out of, especially as she leans harder and harder on her teeny-bopper smartass son, Tommy. She feeds off the crumbs of personal gratification, even if the shame of “having to make it” punishes her after.

Left with $1.59 from $2,000 after her late husband’s sudden funeral expenses, she should absolutely be trying to fetch some more money at her yard sale, but when Alice glances at an old woman sadly parting ways with a shawl out of her price range, she gifts it before even thinking to name a lower price. Tommy lived in a Mott the Hoople LP 24/7, while Alice tiptoed on eggshells to defuse a husband who hated spending his waking life with her. In comparison to their past lives, the motel-to-motel penny-pinching interspersed with swanky cheeseburger dinners is a southwestern Rumspringa. Oh, but how much more difficult that personal liberation is when you’re a woman. And even in the weird capital of the world, Tuscon, there’s always Monterey. Tommy is babied, but never shielded from his harsh reality: you could chalk it up to Alice weighing the benefits of wisening up your kid to teach them empathy early, but it’s just as likely that it never crossed her mind to shield him. In one of the great double-edged swords of our time, the more you make fun of your snarky kid, the more they learn to be more annoying, and the more incomprehensible their gorilla jokes become.

Most, if not all, of Scorsese’s walk-on characters of all genders contain these multitudes, regardless of runtime. Florence, Dianne Lad’s Oscar-nominated turn as a veteran waitress, is told off by Alice in a misplaced projection of her displeasure with the controlling men in her life, and in a simple refrain that silently bonds the two women, Flo responds “I’ve been dumped on by kings in my time.” Crumpled, Alice thinks, “Shit, join the club.” Through the unifying post-traumatic stress of waitressing, they form a bond as warm as Alice’s with Bea, her neighbor and confidante back in New Mexico. God, Leila Goldoni makes me crumble with the heartbreak of her “Who’s going to make me laugh?” as Alice begrudgingly puts her station wagon into gear to embark into the great unknown; it’s Bea who’s likely to most often utter the title of the film, swallowing tears each time.

Moments after this tearjerking, we laugh our asses off at the first of many road trip montages where Tommy irritates the fuck out of his poor mother. Scorsese and Burstyn gorgeously manage tone, which makes the speed-ramped slapstick bits with Vera, the unnaturally awkward server single handedly thrusting a local diner into pure chaos, that much more glaring. The opening Sirkian titles are his first most outwardly postmodern statement, and then he wilds out immediately with his replication of Judy Garland’s Kansas; it’s the type of nakedly stylistic choice that stems from working with studio money for the first time (and maybe the last). It sort of sticks out like a sore thumb in the grand scheme of things. ALICE DOESN’T LIVE HERE ANYMORE is a phenomenally human movie stifled by movie star performances, its Cassavetes-indebted rendition of hope bumping into a backlot’s version of it. But the actorly presentation of the characters may be to our viewing benefit, this already stressful odyssey of American neorealism lightened by a studio-mandated effervescence that translated to nine-season, 202-episode sitcom adaptation. ALICE DOESN’T LIVE HERE ANYMORE is always a bit more somber than you expected, and lovelier than you remembered, too. As Scorsese’s movies continue expanding into obsessions and obsessives, you don’t need a Bechdel test to ascertain this director’s personal breadth. His films, almost every single one an anthropological insight into the ritualistic machinations of the cult of patriarchy, say more about the American feminine experience than any manifesto written against him.

11. THE KING OF COMEDY (1983)

Oh my God, it’s just like JOKER!

10. CAPE FEAR (1991)

As it turns out, most of the Blockbuster Video normie essentials of the ‘90s are actually batshit insane. Tied with Hawks as the best “one for them” director of all time, Martin Scorsese’s indelible remake of J. Lee Thompson’s already sleazy CAPE FEAR is double-fried chicken with all the giblets; the coleslaw’s extra wet, the beans are bleeding red, and the cream in the hot fudge sundae is curdling. One of two films produced under a six-year Universal deal, it’s an excuse to let Thelma Schoonmaker unleash her most psychopathic tendencies while allowing De Niro to embody the city-leveling faculty of Godzilla. Serial rapist Max Cady read up on The Bible, Marx, and law texts in the clinker for 14 years after his lawyer, Sam Bowden (Nick Nolte), withheld evidence of a teenage victim’s “promiscuity.” When Sam confides in his colleagues, they practically shun him on sight. Folks really value the rulebooks, even when breaking them is the right thing to do. Upon his release, he immediately starts stalking the Bowdens: the emasculated husband, the sultry wife (Jessica Lange), their nubile 14-year-old daughter (Juliette Lewis).

When offered a payout from Nolte, Cady notes that the amount accounts for $10/day, and that’s not even minimum wage. You really think you’re gonna thwart this guy with yokel math? Max Cady will outlearn, out-read, outthink, and out-philosophize you: herein lies the white trash key to outlasting you all. Welcome to Max Cady’s class war. He got $30k from his mama’s ranch so he can buy LaCoste to impersonate drama teachers and have your daughter suck on his thumb. That flirtation between De Niro and Lewis is one of the most evil scenes of all time, a completely diabolical choice to not only foster chemistry between the two, but relish in it. That scene reaches a new level when Lewis steps over De Niro’s line and they both just roll with it as nervous, bonding banter. Your whole body shutters when Cady’s fingers glaze over her retainer. Jesus Christ, it’s really not fun to write. Max prepared a whole script every year he was in the clinker, and the form matches the extent of Cady’s treacherous preparation. Perhaps the most virtuosic segment of CAPE FEAR is one in which Marty projects fireworks on the Bowdens’ home windows, transitioning to a split diopter two-shot of Nolte brushing his teeth while Jessica Lange carries on with herself, to a slow pan over their married bodies making love while the image goes in and out of monochrome, overexposed flares, back to black-and-white, back to color, and then immediately washed out with a blinding yellow blackout to match the fireworks in the backyard that, surprise, Max Cady is lounging in front of. Breathtaking.

When Dani’s parents kick off another round of screaming, she slams her door and drowns them out with Guns N’ Roses’ “Patience,” the sequestered impasses of the American nuclear family injected with the purely destructive adrenaline of RAGING BULL’s artillery of punches. Schoonmaker’s legendary remark that “the movies aren’t violent ’til I edit them” most applies here. In its bludgeoning conclusion, De Niro may have tied up the Bowdens, but he’s suffered Toxic Avenger-grade burns. It doesn’t stop the camera from audibly “thwip”-ing between Cady’s distorted mug speaking directly into the lens and roleplaying with Nolte, who’s torn between faith in his legal oath and to the self-righteous justice for a victim who’d be demolished by that very oath. How do you actually defend a life? Scorsese is cranking the nastiness to nutty levels of bad taste, but being a Universal picture, Cady is defeated by his captive family—beaten to a pulp and handcuffed to a drowning chunk of debris. Before Sam can finish pondering if blood can be wiped from his hands, huh, the blood completely wipes from his hands. No matter the circumstances that brought you there, and no matter the orbiting consequences that may land at your feet, if you’ve dedicated your life to exterminating evil, then sometimes the guilt does wash away. Come back soon now, ya hear?

9. KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON (2023)

Frothing with white-hot rage, the type that clouds around your heart in perpetuity, KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON is one of the few pieces of art that I’ve felt capture my own sense of constant anger—an anger that nears an all-consuming hatred that’s equalized itself into my sense of self. The whole of its perspective is in its opening burial of a sacred pipe by a discerning Osage council dreading the inevitable. The white devil will come for the newly erupted oil, for our culture, for our bodies, so we may as well blow some bands. The Osage knew exactly what was happening to them—they weren’t blindsided. The scene I can’t shake is the killing of Anna Brown, repeating “You brought me here to kill me,” as her drunken hand is led into death’s ravine. Her awareness is punished, her corpse defiled with cleavers by the Fairfax medical specialists. It’s omitted from the film, but David Grann’s book details how her skull was missing for almost a century. The undertaker had kept it until 1921, when it was given to bureau agents for analysis, and then ended up in the hands of an unspecified John Doe.

There is no mystery in this true crime tall tale. William Hale, standing in as don of the white master race, is resolute that he could spend the Osage wealth with more savvy—more grace—than the savages could. It’s equal parts delusion and snake oil-hawking, a lie so ingrained that even the liars have begun to believe it. In the words of Lord Curzon, “To feel that somewhere among these millions you have left a little justice or happiness or prosperity, a sense of manliness or moral dignity, a spring of patriotism, a dawn of intellectual enlightenment, or a stirring of duty where it did not before exist—that is enough, that is the Englishman’s justification in India.” There’s the question of what convinced Martin Scorsese he was a capably representative filmmaker to recite this history. Guilt isn’t the basis of his sympathies: it doesn’t take gymnastics to identify Scorsese’s publicly forlorn relationship with a dying cinema and correlate it with a story of the old culture being violently erased for a new one.

In the film’s final triumph, Marty performs the SCHINDLER’S LIST boogie, pulling out from three hours of traditionalist storytelling to let a mocking theatre troupe condense years of anguish into a diminutive segment of FBI propaganda. It’s a perfectly constructed radio play for those who complain about KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON’s runtime; the American Indigenous were systematically exterminated over the course of 600 years, so if someone could write me a guide of how to break up this 206-minute movie into a mini-series, I’d really appreciate it. Scorsese himself cameos as the radio play’s producer, the Lucky Strike-sponsored programming impeded by the real world of Apple-backed programming. He tearfully reads aloud Mollie Burkhart’s obituary, noting that all the events we’d just seen unfold were not mentioned. Thankfully, we pull out one more layer as the present-day Osage take claim of the motion picture.

It’s all as hopeless as it is retributive, but there’s a heavier pour of the former. Turns out the cinema does have its limits. We can adjudicate history but the image can never right the wrongs. “White guilt” is far too simple a concept. Instead, perhaps the guilt of a life dedicated to cinema, finding that the medium’s innate moral obtuseness has never provided a total social net positive. The artist has never seen themselves as savior of the people—that’s not what they explored cinema for—but it’s nonetheless sobering learning that the option never existed. The movies cannot solve a single thing. Coming from the man who’s made it known that movies were his everything, my knees buckle. Naturally, the follow-up question is a chiefly more dire one: what does? How do we trample? What is the eye that repents for this gouged eye? Mollie Burkhart directly pleads to the President of the United States and receives a blank-stared “Thank you.” Later, her remaining sister is obliterated in a bomb blast below her mattress. The only proportionate reparation is a mandated mass suicide of the millions of perpetrators’ bloodlines, so Scorsese instead martyrs the collective memory of the still-living, besmirched Osage.

One of the great joys of working through Scorsese’s filmography is keeping track of which questions he’s satisfied with the answers to, and those he keeps swirling in his head. Most exciting about FLOWER MOON is that, in his 80s, Martin Scorsese has asked a brand new question. Most tragic is his openness over how little time there is left to answer it. This is not the work of someone who’s prepared to finish anytime soon.

8. THE DEPARTED (2006)

THE DEPARTED better matches the descriptions I’ve read of AFTER HOURS: labyrinthine, borderline goofy farce that guides bureaucratic lackeys through the equally entrenched and meaningless social rites of the American urban playground. It’s pound-for-pound one of the best dark comedies ever made, savage crime buffoonery anchored by an endless series of life-or-death gags. The oft-derided green-screened rat that concludes the picture is beyond unsubtle, it’s the Merry Melodies fanfare bringing the bloody affair to a close. Sylvester the Cat found flattened in a gravel alley; Daffy Duck has been shot in the face point blank by Elmer Fudd. How else do you reckon with Vera Farmiga fiddling with a banana while casting affirmations to her boyfriend and his broken penis? Or Jack Nicholson’s blood-gurgling death that inexplicably ends with his arms outstretched on a bulldozer crucifix? Baldwin, in the first trimester of his alcoholic bloat, soaks his face in ice water at his work desk for no explainable reason. A second rat is found in Frank Costello’s Boston gang of middle-aged hooligans and the primary grievance is that the guy who hid his body can’t fathom how dirty he had to get digging in the mud just for the police to find the corpse so quickly. Martin Scorsese has been open about his desire to direct all second unit photography himself, meaning that for at least 15 sustained minutes—in his 60s—he was staring at an insert of a foot-long dildo.

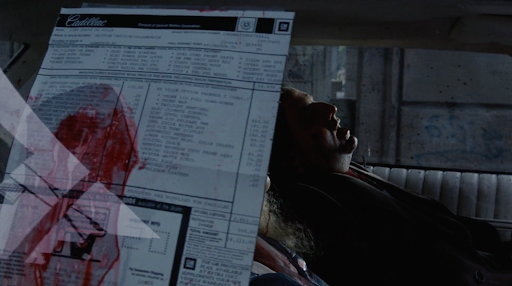

When directly compared to Andrew Las Wai-Keung and Alan Mak’s chilly and folkloric INFERNAL AFFAIRS, the Northeastern flop sweat is more pronouncedly gritty, the fates much less sacred, and the interdisciplinary warfare so much grimier and tactically incoherent. Characters engage with the plot as though they are actively trying to get murdered, and they do! There is no cool, no collection, and even less introspection. I’ve watched THE DEPARTED nearly a dozen times and I’m still at loss as to why Matt Damon’s lunkheaded Sullivan remains so loyal to Frank Costello: from what I can gather, it’s the cop salary that’s paying for that premium condo. Nicholson’s Costello, adorned in Beetlejuice fits and Joker suits, holds claim to a criminal empire constituted of seven walking coronary failures and a loft that looks chintzier and cheaper than his own mole’s. His early days are spent extorting $45 from corner markets that sell month-old bologna, and it certainly never seems like those small-fry days are ever put behind him. He claims early that “I want my environment to be a product of me,” and so Scorsese abides with one of his uneasiest structures, off-kilter because it’s following CASINO’s “and-then’ing” but within a BOXCAR BERTHA straight-and-narrow adult programmer. THE DEPARTED is about the American police officer as inherently violent psychopath, taught to weep for their assigned psychiatrist after discharging their weapon by the TV shows that urged them into the position in the first place. Damon is otherworldly, clearly teaching DiCaprio how to play Ernest Burkhart in 17 years, his square skull maximized by the indignity of Michael Ballhaus’ television-adjacent photography. There’s no glitz, no glory, and certainly no justice in what amounts to a vision of America nearly bleaker than TAXI DRIVER. And yet, perversely, it is one of Scorsese’s greatest entertainments, a film that provides the same comforts as a syndicated SEINFELD re-run. It’s about as funny, too. Sweet dreams.

7. MEAN STREETS (1973)

Shot by the Corman crew of BOXCAR BERTHA in a shocking combo of Los Angeles interiors and New York City exteriors, MEAN STREETS stamped Scorsese’s mark as a quintessential 20th century American artist. The sullen authenticity of ON THE BOWERY utilized to subvert the paperback spectacles of the Northeast Mafia, authored by creative collaborators who keep returning to the core influences of Abbott and Costello, rock’n’roll, and the ways movies would influence your own understanding of yourself. Scorsese bartered over more and more shooting days in New York, and it’s those desperately fought-for travel dates that fuel the kaleidoscopic, manic montage of the interactions, faces, moments, and places that foment in childhood and never quite adhere to logic as your recollection matures. MEAN STREETS is a miraculous collage of formative visions living in the purgatory of childish wonder and wisened decontextualization of all those tough guys in suits you wanted to be. Growth is learning that they were absolute loser, penny-rate, gangster mooks, but adulthood is learning about the communal expectations that cast them astray.

The handheld camerawork (more a financial and logistical limitation than a full-throated aesthetic choice) imbues a rawness that never left. In the director’s own words, “the camera tracking implies more violence than there really is.” His camera peers through the cracks, nooks, across-the-bar POVs of a lifelong observer, and Charlie, a personal cypher played by Harvey Keitel, is the self-loathing artist’s tortured fantasy. No, you’re not going crazy: that really is Scorsese’s voice recording some of Charlie’s voiceovers. Charlie spends the entirety of MEAN STREETS fearing the pain of Hell; the fire ripping apart your molecular bindings is nothing compared to an eternity of spiritual atonement. Stuck on a meaningless, endless treadmill of stealing a buck may one day set you on a path to helping others… That’s what you keep telling yourself to convince yourself Hell is worth fearing? Pray harder, Charlie boy. The Arriflex body brace tracking shot fixed on Keitel’s mug as he stumbles through a spartan barfly rager is a concise microcosm of the sensorial triumphs of MEAN STREETS: the daze of secular distractions, the confusion of sober dogmas.

Had Ellen Burstyn never extended Scorsese the olive branch for the post-EXORCIST character drama she had loaded in the barrel—and he returned to his position as Corman journeyman—with the marvelously complete MEAN STREETS he’d still be one of the most important directors of the 1970s. If not for the entirety of the achievement, then certainly for the opening credits, one of the Top 10 Movie Moments ever captured. It’s rare for a performance to work my tear ducts, and rarer for a story’s well-trodden, manipulative beats to make me cry, but I’ve become a sucker for ebullient craftsmanship: the audacity of cinema, the radically contextualized synchronicity of visual and audio doling out what even a bullet to the gut couldn’t give you. “Be My Baby” blares over the speakers as the camera enters a projector of 8mm memories and I am floating. He did it. I am bearing witness to a visual creation that cannot be replicated in any other medium. And through that image-making, I have met someone in their entirety. He’s done it, he really did it, and it’s been barely five minutes. As Michael Powell described it, “with MEAN STREETS he is in direct contact with his audience, from the beginning to the end.” What’s this guy’s fucking name?

6. BRINGING OUT THE DEAD (1999)

With a title sequence in anti-piracy font and Van Morrison’s harmonica screaming over an ambulance siren that’s overlapping with Elmer Bernstein, BRINGING OUT THE DEAD—a shotgun blast to the optic canal—is the uncontested, undervalued, sleeper masterpiece of the Scorsese canon. After the KUNDUN cleanse, the fetid discharges of NYC beckoned once more. For paramedic Frank Pierce, months have gone by having saved no one, Earthlings slipping through his fingers like sand. An epidemic of Red Death overdoses plague the city, described as a mix of “heroin and an amino acid,” requiring 10 times the usual amount of NARCAN. Shoveling through the film grain, and Goodman sweating all over the pale corpse of another heart attack man, it’s Marty at the peak of his hometown scorn. Shaking mad at how it fails the housed, unhoused, ghosts, and the living, the director who introduced “New York, New York” to popular culture condemns the foundational pitfalls of Robert Moses’ grand experiment. “You cannot be near the newly dead without feeling it,” Frank remarks in a voiceover, and Schoonmaker shows us a single-file line of unhoused New Yorkers in slumber.

On the road, it moves like a Safdie Brothers picture directed by an Old Testament God, but in the hospital, where a patient’s bloodied foot in the way of the automatic door is crushed after every new stiff enters or exits, the film plays like a pitch-black sitcom. It’s difficult to discuss any of it without just listing a series of increasingly outlandish, and somehow profoundly moving, set pieces. At a point, you have to let it flow through you: my point is when Cage’s wise guy supervisor barks like a Pomeranian. The tone never balances, forever altering its state from minute-to-minute like atoms fusing and unfusing for an unsustainable 120 minutes. It’s a whole movie of GOODFELLAS’ final 20 minutes; he’s never made anything with this voltage before or since. Cage communicates every fluttering thought on his sleepless face, performing straight Kabuki theatre. There is FACE/OFF maximalism stored up in his tendons that ensures we feel every skittish drip of guilty sweat. Opening up his heart has destroyed the borders that kept him from drinking the pain of his existence into submission, and as he indulges in increasingly extreme vices (from pranking his revolving partners to swallowing homemade pills), the druggy excavation of fallen souls trapped in the historic city’s cobblestone fails to cease. Angels come in many forms. Blast some R.E.M. and stop a blood-soaked, dreadhead, stark-raving mad Marc Anthony from slitting his own throat with a busted Rolling Rock bottle: you become the job.

5. THE WOLF OF WALL STREET (2013)

Don’t get it twisted: if you believe in your heart of hearts that THE WOLF OF WALL STREET endorses its players and their actions, then you may have diagnosable brain damage. I hope you have access to the medical care that you need, and that your caregivers keep you away from heavy machinery and firearms. One of Jordan Belfort’s first team meetings sees him relishing in the hunt of MOBY DICK, one of the great misread novels of all time. You go down with the whale, always, but reading comprehension has never been a mandate for The American Dream. The Forbes attack piece that dubs Jordan the titular “wolf of Wall Street?” It drives up his applications: the reception desk is flooded with resumes. The final third where the feds have everyone made washes the film out like days-old beef wrapped in newspaper, in stark contrast to the preceding two hours of maximized color saturation wherein every rosy cheek runs a crimson river: the movie in a perpetual flush, all the skin shining like plastic.

Scorsese has such vehement disrespect for his subjects, and can be more carefree because of it. The seams aren’t just coming undone, sometimes they’ve been omitted altogether. Note the obvious zipline of the introduction’s human projectile, the dogshit photoshop of Leo’s tiny face onto that massive head (photos of him as a child exist!), the cross dissolve of Jordan exiting his car to three seconds later where he’s walking a bit closer to the front door of the penny stock broker, and, my God, the cross-shot continuity deliberately tossed to the wind. THE WOLF OF WALL STREET is driven by a JACKASS-level virtuosity, Scorsese and a rubber-faced DiCaprio stretching their conceptions of shock cinema in the confines of American studio filmmaking. Why? To keep themselves interested.