At first glance, WORLD WONDERS and THE FOX EXPERIMENT may have little in common besides their concurrent releases. One is a polyomino game filled with beautiful wooden miniatures, the other is a thematic dice chucker about breeding friendly foxes from the designer of WINGSPAN. The one thing I found them to have in common is that neither game appeared to be selling itself on their mechanics, which is ultimately what will keep me coming back to a game. However, both games surprised me by tackling the familiar waters of open drafting and “take and make” with surprisingly vintage sensibilities. They are not old-school Euros by any stretch, yet some tension and deliberate interaction in the drafting phase was a breath of fresh air.

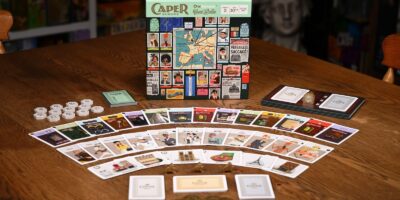

When I talk about “Old School Euros,” I’m referring to a more interactive design school from the ‘90s and early 2000s. Key aspects include a shared space that the players affect, a clean, elegant rule set with little room for exceptions, and direct interactions like area majority (think the area control of RISK except multiple people can inhabit the same space) and auctions. These trends have fallen by the wayside; Euros nowadays are centered around individual player boards, unique player abilities, and little-to-no direct competition. For example, CARCASSONE and WORLD WONDERS both involve placing tiles, but CARCASSONE revolves around constructing a communal countryside as opposed to individually building out a city on your board in the latter.

“Take and make” is a term coined for lighter modern Euros that involve drafting a tile, card, or other items from a pool to use on their board or area; CASCADIA, CALICO, GIZMOS, BARENPARK, CANVAS, and TREKKING THROUGH HISTORY all fit this category, as do WONDERS and FOX. In WORLD WONDERS, you’re spending gold to take Tetris shapes from the market and make a beautiful city, scoring for surrounding buildings, touching various points on your board, and having a diversity of resources. In FOX EXPERIMENT, you draft foxes and roll dice to breed a friendly offspring, which becomes available for drafting in the next round.

This system of open drafting is not antithetical to an interactive game. I’ve already discussed the playmat changing the value of cards in TREKKING THROUGH HISTORY. The complex draft of AZUL, where tiles move from pre-constructed lots to a central pool, creates a delicious opportunity to screw over opponents since the tiles move in a predictable pattern. Similarly, COLORETTO allows players to either add a card to one of three set pools or take one set themselves, meaning they might choose to push their luck and add to a pile only for someone else to take it. However, most interaction in “take and make” games boils down to taking something someone else wants, also known as hate drafting, which can be intentional but is often inadvertent and thus unsatisfying. It gets even worse when the item you took gets replaced by something even better for your opponents.

Hate drafting is more prevalent in WONDERS and FOX EXPERIMENT compared to other take and makes, because the market does not refill like it does in similar titles. In CASCADIA, when you take a habitat tile and animal token, they are immediately replaced. That is not the case in either WONDERS or FOX EXPERIMENT. Once someone takes a tile in WONDERS, there’s no accessing that same shape until the next round. Similarly, it’s first come, first serve with the foxes and their associated dice; if you go last in turn order, you’re crossing your fingers that the trait dice you need are still there when it’s your turn.

Speaking of turn order, I prefer games to go beyond the clockwise orientation, and FOX EXPERIMENTS and WORLD WONDERS have composed interesting mutations. In FOX EXPERIMENTS, players need to select three items in the drafting phase: two foxes, one of each gender, and the turn order for the next round, along with a randomly set-up bonus. These can be taken in any order; one player might decide to grab the one great male fox on the first go-around, while their successor might decide to grab the first player token in the hopes of grabbing a spectacular pup next round. I can’t think of any other examples of having to grab multiple items in a player-determined order like this. It forces you to pay attention to what other people have already selected and how much value you think you can get later compared to now.

For example, if the other players all select a female fox before you, then you can delay that selection until later. There are always more turn markers than players, and players can choose to forgo any sort of bonus token to guarantee to get first picking in the next round. The game possesses a steep progression, so it’s likely the foxes bred for drafting will be better each round. Is it worth getting that first-player marker and settling for a worse fox this next round because you’ll be able to select one that is that much better in the future? This constant flow of changing values is at the core of many of my favorite games, and this three-stage drafting process was a welcome surprise. It further illuminated how AFTER US, whose card moving system is not that different from the die-rolling and pattern creation of FOX EXPERIMENT, needed a slightly more interesting card acquisition system to sing for me like FOX did.

It’d normally irritate me that only one of each shape is available each round in WORLD WONDERS, or that you might need a certain building type that never comes out. However, there’s the option of buying the first or second-player marker, so you can stop leaving matters up to luck and practically guarantee you get what you want. The titular wonders are intrinsic to this system as well; each of them needs to be built next to certain objects, and they bestow various points and resources onto their owner, in addition to having larger shapes that help with filling your board. Their genius lies in their cost. Rather than having a fixed cost, they require a player to spend all their remaining gold, taking them out of the running until the next round.

A whole new element of pushing your limits is born out of this mechanism. The ideal situation is spending all but one of your gold for maximum efficiency, but giving more time for your opponents to swoop in and take the pyramids or Machu Picchu right out from under your nose. Unlike normal buildings, the wonders immediately refresh, but their unique shapes and requirements mean it’s unlikely a new offering will fit into your existing plans. Is it worth grabbing that wonder earlier, forcing you to spend more gold, or pushing your luck because you’re pretty confident that nobody else can take it because they do not have the requirements? In a game where you’re largely focused on your own board, these wonders become an important battleground that forces you to pay attention to your opponents to gauge how much of a threat they are of thwarting your plans.

The core frustration of old-school Euro fans with modern trends is two-fold. First, it’s hard to tell how and what your opponents are doing, which can be a problem with all the buildings in WONDERS and all the dice in FOX. Second, even if you can tell, there’s little reason to because you cannot affect them. On this account, WONDERS and FOX bridge the gap between old and new by adding much-needed tension and competition to open drafting systems. Both have gotten attention for things outside of their core mechanisms, but both deserve more praise for doing work to actually refresh the increasingly stale “take and make” model.

Comments