The story of the Yakuza series’ rise in North America is an interesting one. Originally released on the PlayStation 3, the first three or four games failed to really crack the mainstream, but did develop the cult-like following that certain games need to sustain themselves. Around YAKUZA 5, the game started getting more and more attention, until finally the wildly popular prequel YAKUZA 0 was released. Some of those fans were popular streamers and Let’s Players, who began showing off the brutality and eccentricity of the series, getting others more and more interested. With the North American release of the remake of the original YAKUZA, known as YAKUZA KIWAMI (“Kiwami means extreme!”) the series was finally laid bare as an exciting and oftentimes bizarre Japanese tourism simulator alongside a minigame collection, brawler, and winding crime story.

YAKUZA 6: THE SONG OF LIFE was not exactly a solid bookend to the story of Kazuma Kiryu. While closing the door on the aging ex/current/former/disgraced/ascendant Yakuza member and his time in Japan’s criminal underworld, it absolutely left open the possibility that Kiryu would return in some regard. So when trailers started appearing featuring Ichiban Kasuga (or Kasuga Ichiban if that’s how you wanna do it) the general community was somewhat taken aback. And if that was a surprise, it was nothing compared to the introduction of YAKUZA: LIKE A DRAGON’S JRPG turn-based battle mechanics that would replace the tried-and-true button-mashing. What started out as an April Fool’s joke that developers started running with became one of the biggest variables to the success of the game. While the reason the developers went with it was because of the fan reaction, still others wondered if it would feel like a Yakuza game.

Your combos are gone but you can still beat up anime fans with a pipe

I cannot imagine the tenuous dance Toshihiro Nigoshi and the rest of the developers have been doing to give YAKUZA: LIKE A DRAGON the care it needs to feel faithful to the game’s longtime fans as well as the curious gamers who were attracted to the madcap chaotic energy showcased in Let’s Plays, while still making it feel fresh and new and separate from previous iterations. Nigoshi has become somewhat notorious for having a devil may care attitude toward what goes into the games, but I imagine it’s still a tense situation for the Ryu Ga Gotoku team.

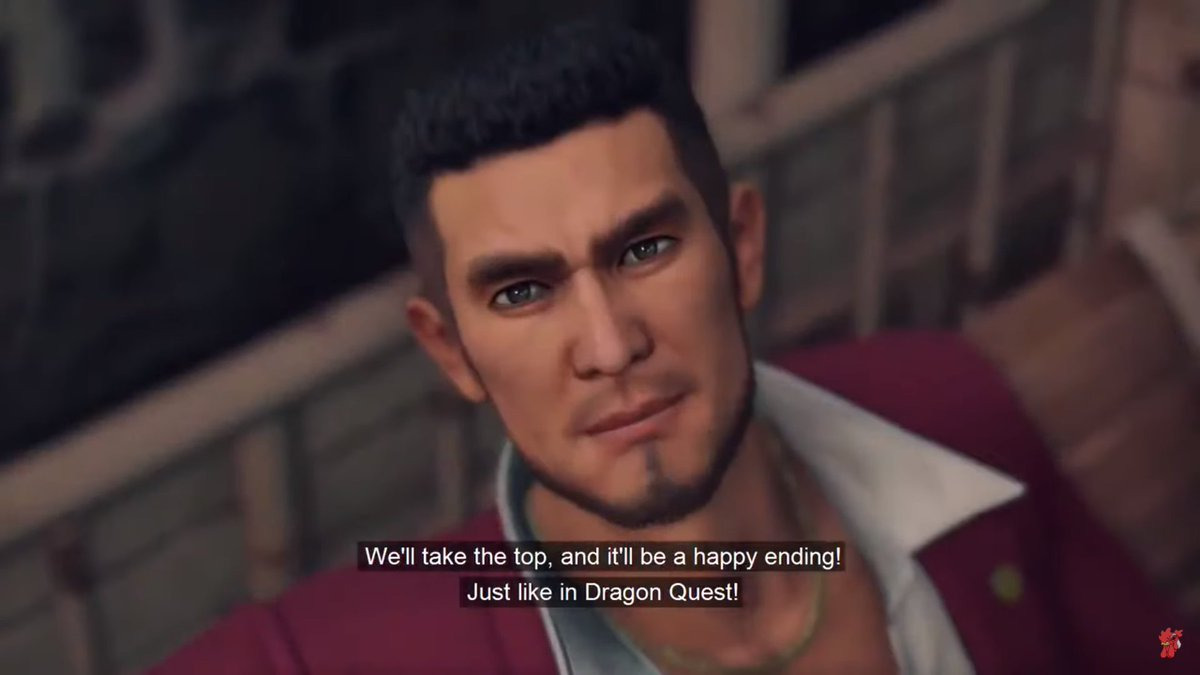

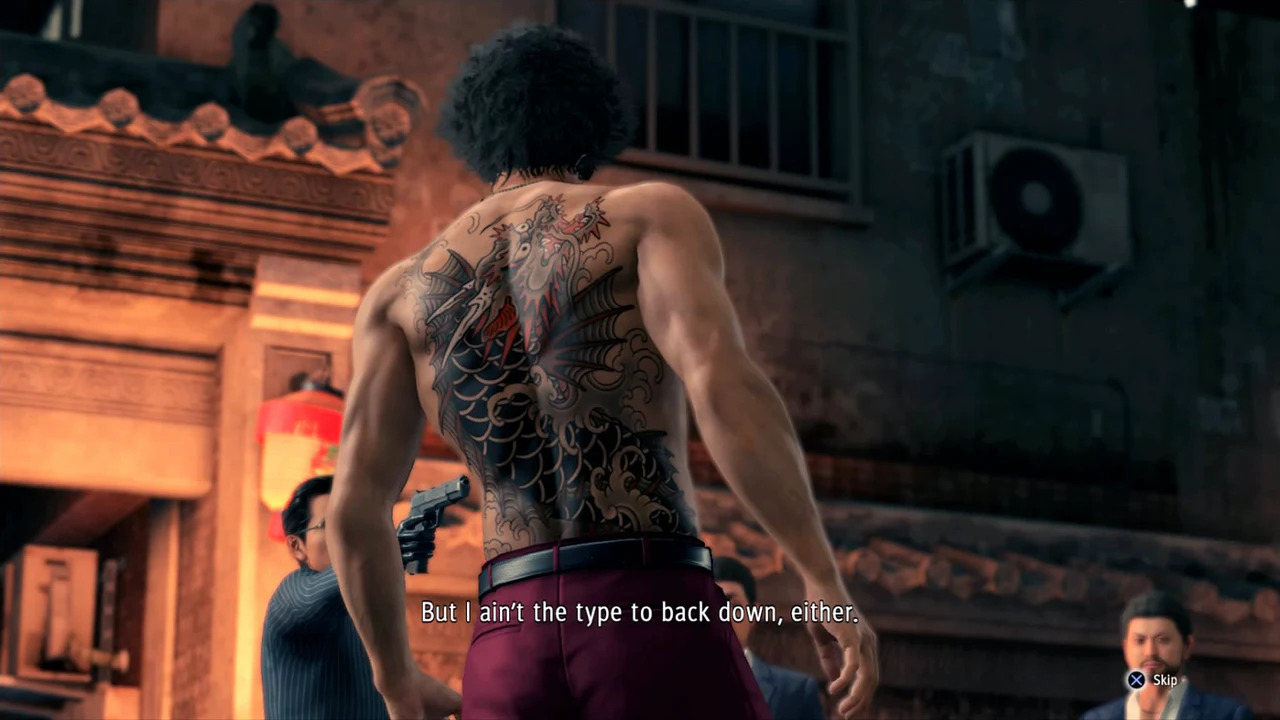

Gone is Kazuma Kiryu, along with the district of Kamurocho, traded in for the wild-haired Ichiban Kasuga and the riverside city of Yokohama; the difference between the new protagonist and the new city (which in some cases is its own character altogether) is apparent. Ichiban is obsessed with the Dragon Quest series, and sees life through that very specific lens. He’s also a huge goofball, and kind of an idiot at times, a far cry from the stoic and usually level-headed Kiryu. Like Kiryu he’s an orphan as well, growing up alone at the Shangri-La soapland in Kamurocho, the same one that featured heavily in the first YAKUZA game. He also found a father figure in a high-ranking member of the Yakuza who essentially saved his life. And like Kiryu, he is sent to prison to cover for someone else, and is further betrayed by this father figure once he gets out.

You could say he’s the whole…character you’d expect from a Yakuza game

So there are familiar story beats here, but THE FORCE AWAKENS tried this once already, and it didn’t seem to help the film much in the long run. Still, the real adjustment is to the new fighting mechanics. Earlier Yakuza games were focused on landing small combos, occasionally switching between fighting styles depending on the situation, and unleashing brutal heat moves on riled-up gangsters. I’ve written before on how deeply satisfying this combat can be, so I was among those concerned about what would happen to the often-frenetic pacing of combat if it was entirely switched out for a more pensive, turn-based JRPG style. As one might imagine this isn’t a realistic style of fighting, especially for cutthroat criminals, but it’s explained away as somewhat of a delusion Ichiban experiences when he gets into fights, translating them into something similar to Dragon Quest, which seems mentally more palatable for him.

Yeah, whatever, NERD

The RPG mechanics are supplemented by a robust Job system, which figures into the main story’s themes of poverty and homelessness. Jobs act as a class system, with the player able to select different classes/abilities for themselves as well as other members of their party. The jobs offered include things like Musician, Host, Hostess, Chef, Breaker (a break-dancing class that gives the character baggy clothes and a sick bucket hat), as well as Bodyguard, Idol, and Night Queen, which is literally just a dominatrix. Like classes in an RPG, each Job has their own strengths and weaknesses as well as ways to play them, and it’s up to the player to mix and match to find the right playstyle they’re looking for.

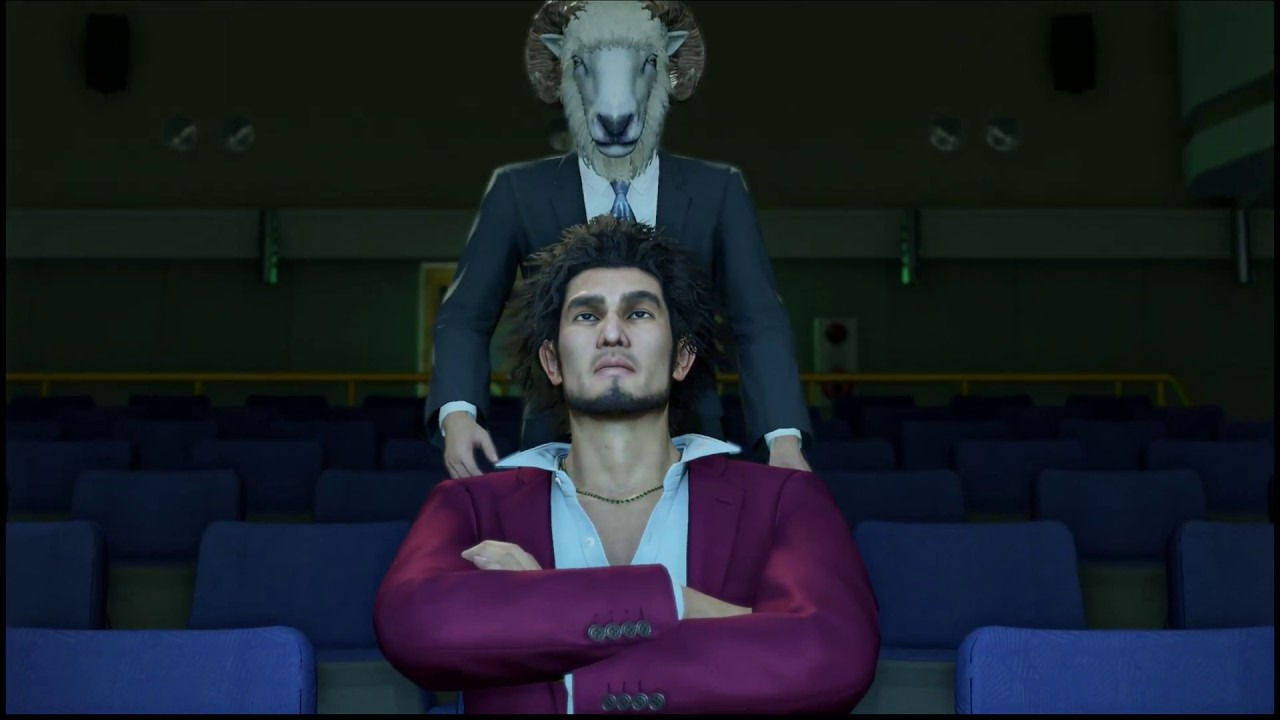

For those concerned about the integrity of the game’s overall tone, it’s important to remember that Yakuza’s tone is at its best when it’s all over the place, and this extends to the battle system. While players can unleash devastating attacks that include smashing enemies with baseball bats, breaking ashtrays over their heads, grilling their faces over stovetops, and slicing them with katanas, you can also engage in attacks where you sing a song of peace so good it lowers the attack power of enemy combatants. It’s also important to remember that this is a game where you can call an army of crayfish to assault your foe, or a yakuza leader dressed as a baby if you’re so inclined. There are moments in-game that shift the tone so neck-breakingly quickly that all you can is lean back and go “That’s a Yakuza, baby.”

Me about to tell you this is where Viggo broke his toe

Unfortunately, not all of LIKE A DRAGON’S faithfulness to the games that came before are positive. Fans of Yakuza are familiar with the dark and gritty crime narratives, but the complex layering of clans and gangs and cops that make up the story sometimes only serve to obfuscate it and hamper the overall pacing. Pacing is somewhat of a problem in Yakuza games, and LIKE A DRAGON suffers from the same issues. As Ichiban’s character is much more affable and lighthearted than Kiryu, the cutscenes have more opportunities for comedic diversions, but the overall crime drama concerning betrayal, exile, and rushing to prevent an all-out gang war feels somewhat par for the tonal course as far as Yakuza goes,as does the way the narrative moves or doesn’t move. The story is split into 15 chapters, and certain aspects of the game don’t unlock until at least halfway through the story, which can add to the somewhat plodding feeling of the overall plot. But again, that’s a Yakuza, baby.

All I really know is that whenever this happens shit is going DOWN

YAKUZA: LIKE A DRAGON is an ambitious take on a tried and true formula, but it would’ve been nice if there were certain areas that saw more polish and perhaps innovation. Those new mechanics bring an alternate perspective to the series just in time to introduce its charms to a wider audience. It’s still a blast, and a delight to play and offers all of the things that’s catapulted the Yakuza franchise into more mainstream recognition.

Comments