To a significant portion of modern players, the Metroid series exists more as sacred text for the popular Metroidvania genre than as actual games. Between METROID PRIME 4 restarting from scratch, “y can’t Metroid crawl,” and the metaphorical doghouse the franchise sat in mostly uninterrupted for nearly two decades, the influence of the original 2D games is all many younger players have to go on in anticipation of this surprising, supposedly final new entry in the legendary series.

I count myself among this group; I’ve played some great Metroidvanias, from Image and Form’s STEAMWORLD DIG games, to what I herald as the crown jewel of the genre, Team Cherry’s HOLLOW KNIGHT, in addition to consuming many video essays and other writing on the genre and its genesis. METROID DREAD however, was my first true Metroid game, aside from hopeless attempts at the original long before I understood the mechanics and history of the series enough to want to beat my head against its inscrutable challenge. I went into DREAD with high expectations and a resolve to avoid walkthroughs at all cost; it felt essential to play this landmark game in as pure a manner as I could, to test whether it could uphold or exceed the standards of the genre it birthed.

The result? I came away impressed by the risks DREAD takes and the implementation of its mechanics, but underwhelmed by the game as a premier entry into the vaunted Metroidvania formula. Make no mistake, this is a fun game with numerous high points and excellent flow, but I found myself wishing for something a bit different than what I got more times than a really great game can allow. Perhaps undone by my expectations, I wanted a game that would challenge my mastery of its combat, test my navigation skills, and immerse me in rich atmosphere and background world building. While METROID DREAD succeeded at the first objective, it stumbled on the latter two.

You’ve got to get used to doing a lot of parrying.

DREAD’s combat and movement are its strongest attributes; though many players will wrestle with the ever-expanding list of button combinations, Samus mostly controls fluidly and gracefully. I struggled with the Space Jump, sometimes missing the timing to continue gaining height, and with initiating the Shinespark, a rocket-like advanced maneuver. It and the speed boost are fun to use, which is a shame since the main quest rarely calls for their use beyond finding optional pickups, often hidden behind confusing hidden block puzzles. These are minor quibbles in an otherwise satisfying package, one that sees Samus zipping around the planet ZDR’s maze of corridors, picking up a steady stream of abilities which greatly increase her mobility and combat options. The pacing is brilliant, doling out new toys and gradually accelerating the tempo of the adventure as Samus evolves into an acrobatic, missile-firing menace. These qualities are most notable in the frantic, outstanding boss encounters, challenges that feel insurmountable until you learn the patterns and gain the ability to glide effortlessly around screen-filling attacks, which I found addictively fun through the final battle.

Despite the strength of these encounters, combat in the main game can begin to wear thin. Dread packed the many corridors of its world with a narrow variety of enemies, made even more cumbersome after a mid-game event replaces all enemies with a respawning parasite, sometimes morphing into another enemy after the first iteration has been killed. These occurrences slow the pacing and require nothing more than waiting for the parry cue, a cool move that becomes a chore after hours of repetition. Repetitive combat is a sin many games commit, but it’s less forgivable in a series that was primarily built around isolated, tense exploration. Older games found a balance between leaving Samus alone and putting her in combat scenarios; DREAD lets up only in biome transitions, otherwise inundating the player with rote combat encounters, making the sense of “dread” and isolation on a hostile planet less impactful. It’s harder to get lost in the shoes of a solo explorer if that explorer is constantly forced into encounters.

As was repeated ad nauseum in the lead up to METROID DREAD, the qualities that define this genre owe a direct, substantial debt to the groundbreaking design of the Metroid series, particularly its hallmark nonlinear exploration. I expected Dread to let me get lost, and in turn let me find my way through its world. A well-conceived and well-realized Metroidvania map can still challenge and frustrate, but should provide enough clues and the light touch of a mostly invisible guiding hand to nudge the player in the right direction. That hand has a complex, integral role in Metroidvanias; it must guide unseen, allowing the player to feel as though they are untangling the knot of the map themselves, while providing just enough signposting and guardrails to prevent the player from truly getting stuck. DREAD is unfortunately heavy-handed in this regard, and it ruins the sense of self-guided exploration.

Even with wide open levels and branching paths, DREAD feels surprisingly linear.

I can recall only one or two points in the game where I felt like I was truly let off the leash to find the next step, when I hoped for far more. Instead, DREAD uses a classic tool in the Metroidvania toolbox to a fault, creating “points of no return” when certain thresholds are crossed. Dread has many of these: collapsing floors, poisonous Enki plants, one way doors, redirected power, impassable temperature zones and more. These points of no return are so frequent that instances where a significant chunk of the total world map is actually available to the player are rare, and “exploration” more often feels like being steered towards an objective than a puzzle to be solved. Samus may be pinging between regions and uncovering new paths constantly, but I rarely felt as though I owned the satisfaction of doing so.

Atmosphere and world building are the other weaknesses of DREAD, not bad by any means but lacking the environmental storytelling touches that DARK SOULS or HOLLOW KNIGHT used so effectively to scaffold their worlds. There are fleeting moments, like the impressive zoom-outs when entering a tram station or the sight of the carcass of an early boss being experimented on, but DREAD does little to prop up its threadbare narrative with atmospheric and environmental detail. There’s not much of a story to speak of either, with nonviolent interaction mostly limited to monologues from a humorless AI, though there is something to be said for allowing the gameplay to shine mostly unimpeded by interruption. Put another way, I knew little about the broader Metroid story going into DREAD, and I know about as much after it. Hell, there’s not even an appearance from the titular Metroids, continuing the LEGEND OF ZELDA tradition of naming Nintendo games after something other than the protagonist.

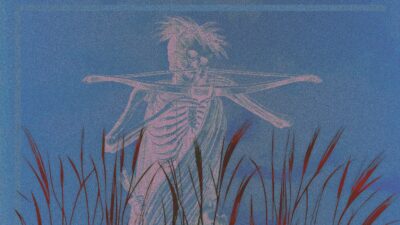

The emphatic exceptions to this rule are the E.M.M.I. (Extraplanetary Multiform Mobile Identifier), stars of the game in their own right and principal suppliers of the promised dread. The eerie, agile robots are a great mechanic skillfully implemented, ramping up the challenge over time so the player never feels comfortable in an E.M.M.I. zone. Cruising through the regular game only to hit an ominous pixelated door always led to a brief pause to steel nerves, before entering cautiously to peel apart the hide and seek puzzle on the other side. These are definitely puzzles more than enemy encounters, particularly when later E.M.M.I. can sense the player basically anywhere. These sections flip the power dynamic, forcing careful movement and often requiring the player to venture bravely into unmapped territory hoping to find a hiding spot before being assailed. These encounters are deliciously tense and the penalty for failure isn’t steep enough to cause much frustration (though getting zapped and rendered immobile from three rooms away might). The imbalanced power and nearly mandatory failures make the eventual acquisition of the Omega Cannon in each zone a moment of high drama, ratcheting up the intensity towards a final showdown that always left me breathing a heavy sigh of relief when conquered.

Encounters with killer robots are never not scary.

The sound design in these zones is immaculate, full of unsettling beeps and far off clanks that make the choice to move feel like an agonizing risk, a quality that compares favorably to the pit-in-your-stomach feeling activating Guardians early in the LEGEND OF ZELDA: BREATH OF THE WILD generated. The inclusion of these robots was a doubly risky choice for Nintendo, as the narrow solutions to each instance runs counter to the otherwise nonlinear structure of these games, and the level of anxiety and challenge goes beyond what I thought the family-focused company would be willing to include at this stage in its history.

METROID DREAD is a game many thought would never be released, so its mere existence is worth experiencing and celebrating. That it includes some notable risks from Nintendo is encouraging, and the overall experience of playing is an inarguably satisfying one. Unfortunately, the years of separation from its predecessors allowed a genre to evolve in its absence, and in doing so Metroid left behind some qualities that made those forebears great, or ceded the throne to others who captured elements of their spirit more effectively. DREAD is thus easy to recommend, but not the masterpiece it could have been.

Comments