What Andrei Tarkovsky wanted from his viewers was patience—a simple kind of attention not catalyzed by an agenda. Tarkovsky hated when fan mail would call his films inaccessible or elitist; the latter comments hurt especially because he thought of his films as being for common people. In one of the opening scenes in his 1974 film MIRROR, for which he received plenty of negative fan mail, a man takes a moment, after having fallen to the ground, to appreciate the vegetation around him. “Has it ever occurred to you that the plants are feeling and being aware,” the man says, “perceiving even… They are in no hurry. While we rush around and speak in platitudes. It’s because we don’t trust our inner natures. That’s all our doubt, haste, and lack of time to stop and think.” This musing is Tarkovsky’s most direct conversation with his audience. He’s asking his viewer to take their time with the movie, to think of it more like poetry: not to be “understood,” in any conventional sense, but to be felt and, just as importantly, to not conflate accessibility to the amount of time a viewer spends on “figuring out” the film. This is a peculiar position coming from the director of some of the most complex, convoluted, and philosophically dense films ever committed to celluloid. It is true, however, that Tarkovsky’s films are at their most digestible when they are each mediated on and deeply considered, which is why I, in anticipation and preparation of Janus’ new restoration of MIRROR, force-fed myself four Tarkovsky films in less than 24 hours.

I had to satiate a cinematic tick of mine wherein I must watch a director’s films chronologically before I can watch any of their films individually—which is dumb, but it pays the bills (it doesn’t). So I needed to watch the three films that preceded MIRROR all in time before its new restoration was watchable via the Lincoln Center’s virtual cinema. My mistake was that I thought that January 29th was the only date the film would be available, so I went ahead and ruined a few days of my life by spending over 10 hours trying to decipher and crack codes Tarkovsky never wanted me to crack. The idea felt a lot like a stunt from JACKASS, subjecting myself to cinematic torture for the sake of spectacle. And for my next stunt I’ll snort Sriracha off my Criterion Blu-Ray of A BRIGHTER SUMMER DAY.

The stage was set: I had a candle lit, I ate a healthy lunch, I stretched, I told my girlfriend I loved her and that I was sorry in advance for the person she’d have to live with for the next 24 hours. So began the quest. With mind and body prepared, I watched IVAN’S CHILDHOOD, a post-Stalin anti-war film that follows a young orphaned boy, Ivan, who weasels his way into being a front line spy for the Soviet Army during the Second World War. Heavy subject matter? No problem! A cinch I figured. And truly, the film, beyond its surrealist imagery and editing style, wasn’t “too” heavy, and was by all accounts accessible. My mind didn’t transcend my body, I wasn’t paralyzed by philosophical sudokus, and I actually, if you can believe it, enjoyed myself—as much as you can in a film that depicts the brutality of war.

IVAN’S CHILDHOOD introduces some of Tarkosvky’s signature traits: non-linear narratives, juxtaposed realities, bleak and honest depictions of the state of the world, and Russian history. Most notably is how the film makes the viewer an active participant. The film cuts so quickly from dreams to present reality to the future that the viewer needs a moment to catch up, to make sense of where they are in the story. Tarkovsky asks that the viewer fill in the blanks and figure out how Ivan went from A to C—in a way asking that the viewer co-author their experience. The hyper-expressionist styling baits viewers along, willing them to push past initial feelings of confusion, eventually helping them get used to the fractured edits, and furthermore helping them engage with this narrative style. I made it out of the film alive. I took a nice stroll around my apartment and patted myself on the back for making it through. “Well, it was heavy, but I really enjoyed it,” I told my girlfriend when she asked how it went. Then I took a moment to consider how I really felt after watching a truly sorrowful film: this whole experience is going to feel terrible.

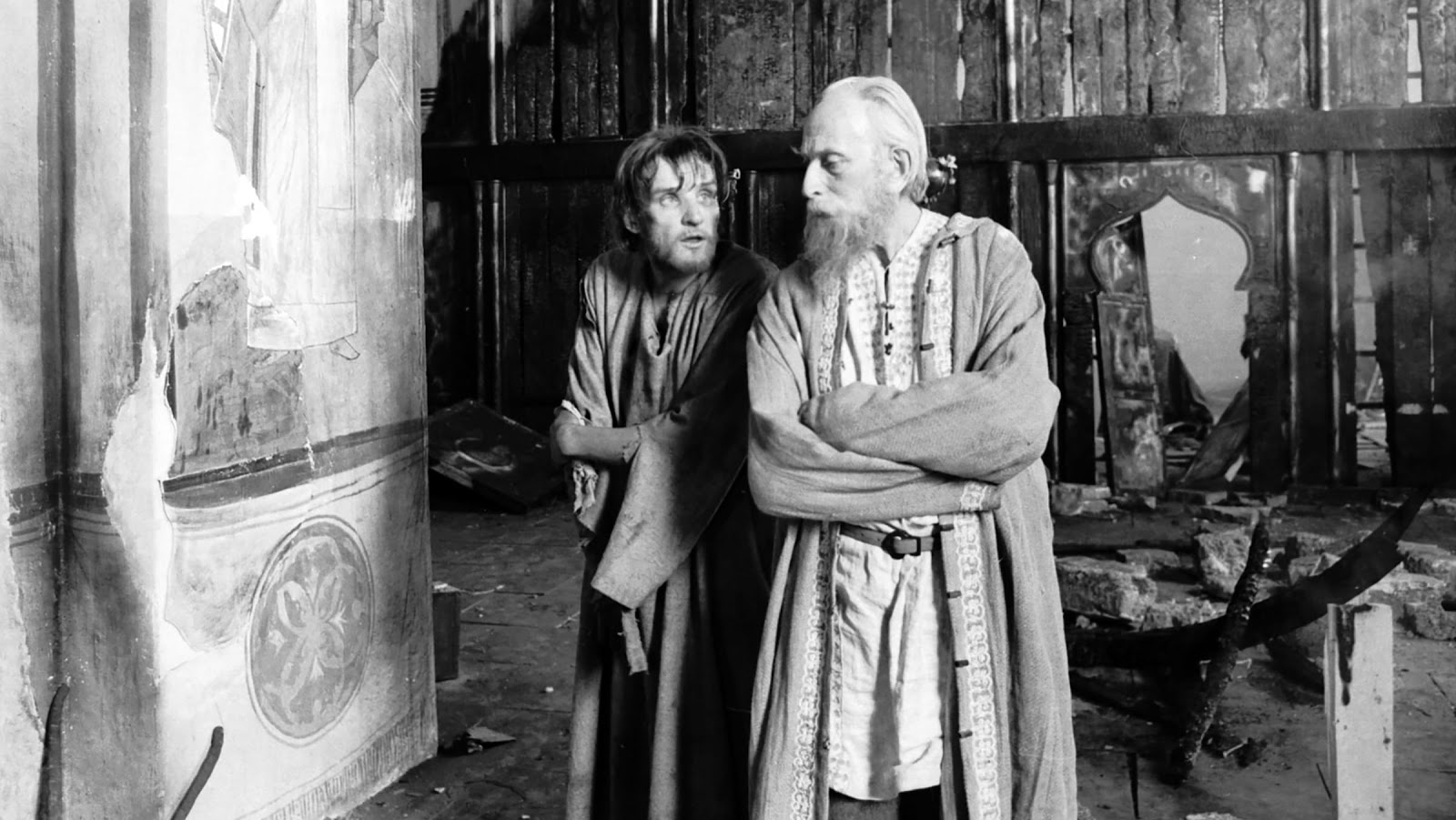

Which of course queued me up something perfect to, a few hours later, hit play on Tarkovsky’s 1966 three-hour historical biography ANDREI RUBLEV, about the titular 15th-century Russian icon painter. A long movie has never been a deterrent for me; more than anything I always hope the director will actually use the length of the film to some effect and not just tell a really long story—hoping they will use time to manipulate the viewer’s experience, whether it be to really ground them in the story, or to make them forget about the beginning of the movie, so that when it’s brought up later, it will actually feel like it happened a long time ago. Plus, time is kind of Tarkovsky’s whole thing. That and horses. He loves horses. ANDREI RUBLEV, more than anything, is a conversation Tarkovsky is having with himself about how it’s possible to make art in such a grim world, a world that is simultaneously responsible for inspiring the art and ruining it. In a world made difficult by government oppression, political strife, and famine, Tarkovsky reminds us of the wonder of introspection. There is a moment, right after a political militia attacks a village, burns down its homes, and kills the majority of its population, where Rublev talks with the ghost of another icon painter. He asks the ghost how long this will go on for, gesturing to the aftermath of the violence. The ghost looks around and says, “I don’t know. Forever, most likely.” The ghost takes in the surviving art on the walls and remarks, “Yet how beautiful all this is.” Tarkovsky had faith that, in the wake of violence, salvation lied in our ability to continue making art. Art, for him, in this way, was political.

It was around this point in the film that I realized I had been grinding my teeth for two-and-a-half hours: a casual response to the grim reality and molasses pacing of the film. Beyond a hint of dissociation, I had begun to lose patience with the film and, as a result, was struggling to pay attention. These deeper truths in the film wouldn’t hit me until afterward, and the film, for all its beauty and profundities, wasn’t quite clicking for me. I chalked up this impatience to the marathon watching and let Tarkosvky off the hook. I still needed a break though. I figured the film would land on more receptive and attentive ears if I just took a little break. I got up and immediately banged my knee against a solid glass table and felt nothing, which was odd because usually that hurt.

Eventually, I finished the film and realized the weight of the grave error I had embarked on. My jaw hurt, I had a random pain in my shoulder, and my exhaustion had peaked. The break I took did nothing. I began to seriously doubt that this experience would actually amount to anything, let alone grant me some unique access to this body of work. To combat these feelings, I thought it best to fight back with knowledge: I started reading every article I could find on Anrdei Rublev and watched every video essay ever made about the film (if I can’t access the “meaning” of the film the old fashioned way, then I’ll beat it to death with analysis). I tried to go to sleep after my Rublev research, but couldn’t. The mental gymnastics wouldn’t stop. Andrei Rublev is really Andrei Tarkovsky. Whoa. The violent feudal government was a lot like the autocratic dictatorship under Stalin’s rule. Why doesn’t my knee hurt? I hit it really fucking hard. My girlfriend was watching the Showtime series SHAMELESS in bed and when I heard the modern lexicon after reading 15th century subtitles all night, my brain started to crack. I wrote a note down in a sleepish haze that said, “This modern slang is the new poetry. I can’t believe how beautiful these characters speak,” right after a character on the show had said something to the effect of, “If God didn’t want us shoving things up our ass, then he would have given our ass a gag reflex.” Eventually I drifted off to sleep.

I woke up at 7 A.M., made a quick breakfast, tried to put sentences together when my roommate asked how I was doing, then started up SOLARIS (1972) by 8 A.M.. I was in a terrible mood. I had already felt confident in a premature conclusion that Tarkovsky was inaccessible and that his films could only be understood through extracurricular reading, which rendered the film elitist shit. I couldn’t help but wonder, though, if the torture of the experience wasn’t actually what Tarkosvky might have wanted me to feel—what a sicko. Perhaps the exhaustion of considering the deeper questions of his films was the type of “access” he wanted, because I was viscerally feeling them. The truth is that I would hardly call what I was doing in those moments “considering the deeper questions.” More than anything, I was just desperately trying to make sense of things as my body and mind continued to disintegrate. Each film was becoming a challenge. Each film became a “me” vs “it.” Somewhere mangled up in the exhaustion of the experience, the content of the films, and the post-film analysis, I could still smell a tiny scent of payoff. I went ahead and finished SOLARIS, a film ultimately about the narcissism of man and on what terms humans define their existence, which felt a little like Tarkovsky trying to wring me by the throat and ask that I stop ruining his films. But I kept on trucking and finished the dang thing.

Finally, as the sun began to set, the moment arrived. I was bruised, battered, grumpy, and weak. It was time, finally, to watch MIRROR. I had finally taken Tylenol so my migraine and shoulder pain weren’t fighting for my attention. I was at peak exhaustion and could not have loathed Tarkovsky more. I hated that his films came to life after they’d ended and only once I spent hours reading about them. So, with shaky confidence and a feeble hand, I clicked play.

Over the course of the film I proceeded to transform in a thin pane of glass. Tarkosvky emerged from the screen, his mustache sharp as ever, his leather jacket crisp. He stood over me and dug his heel, stomping down and shattering me to pieces. As soon as the credits began to roll, I slowly made my way to the kitchen, packed a bowl full of cold spaghetti leftovers, went into my room, and started to eat, my gaze fixated on the corner of my bed. When my girlfriend asked how I was, I almost cried. I was beyond exhausted and mentally nauseous. The film was incredible, or at least I could tell that it was, and that’s what ultimately became the most upsetting realization: I had ruined these films for myself. Which, sure, that was the point of this dumb idea, but MIRROR was a coda that felt catered to combat what I had set out specifically to do. I think beyond the joke of the idea to binge his films, I had a genuine curiosity if not a complete immersion in his brand of dense, philosophical cinema might actually be revealing of something deeper, which I think is finally what happened with MIRROR. It was too little too late by then.

The film navigates the collected memories of a dying poet, edited in a way that are as non-linear and fractured as memories feel to recount, akin to a Picasso portrait painted from multiple perspectives all happening at the same time from a singular point of view. Memory in this film is a collapse of time; the past is brought to the present. The memories present themselves as a black-and-white vignettes, sepia shorts, and newsreels showing the aftermath of WWII. Russian history for Tarkovsky wasn’t a thing of the past. Soviet rule continued and, though not as repressive as it had been under Stalin’s rule, was still restricting. To get a film made, like all of his previous films, Tarkovsky had to appeal to Goskino, the State Commission for Cinematography, which wouldn’t let him make films that were outspokenly anti-Socialist—at least, of the brand of Socialism they practiced.

As the film unraveled I was still so grumpy and weary that most of this went over my head. I finished my cold bowl of spaghetti and began doing the research that had come to fill all lapses between films. Before I went too far down the Tarkovsky dark web, I thought about the passage that opened the film. I began to think that perhaps I’d stand to benefit from subtracting that extra workload from the experience of the film and supplementing it instead with a patient considering of the film and how it made me feel—to let the images most burned in my mind stay without the burden of meaning weighing heavy on them. Like poetry, the film has a potential afterlife as long as the experience isn’t only about “understanding,” but instead attentiveness and patience. I think this is the crux of what angered Tarkosvky the most about reactions to MIRROR: he was operating in a medium that wasn’t synonymous with the poetic work he made. He so badly wanted viewers to walk away having really felt the film, even if that meant they were at odds with it because perhaps Tarkosvky was also at odds with it, wanting the viewers to feel at odds with the frustrations of trying to recount the haunting images of life that we cling on to for fear of forgetting or misunderstanding. He wanted the viewers to feel how present and long lasting the scars of life post WWII were, and that empathy could unite them in this.

This doesn’t of course give Tarkovsky a free pass to make a bad film and blame the viewers for just not “getting” it, nor does it free him from making an inaccessible film and blame the viewers for not “feeling” it. I once asked a friend how to know if a poem is confusing in a good way or bad way. He roughly explained that sometimes a poem is confusing because it wants to heighten the effect of a sudden clarity, but also, sometimes a poem is confusing because something about the poem is not working, but that can also change over time. Poems may not really be about understanding at all, but are more about mental processes, the act of engagement, and the thought provoked. Tarkovsky’s films and poetry are alike in this way. Slow down. Our reactions are valid, yes, but they should be considered. We should also have faith in our initial reactions because those have the potential to lead us to more profound aspects of the art we engage with.

Over time we change, as does our knowledge of the world we interact with. So, too, then do our interactions with art. Perhaps Tarkovsky wasn’t right for you in that moment, but if you have a lingering feeling pulling you back to the film, try it again. Also, it should go without saying, please don’t watch more than one of his films a week. I’ve lost weight, my teeth are a centimeter shorter, I have nightmares of images from the films, all I can talk about anymore is Tarkovsky, and ultimately, I shat all over what otherwise might have been moments of cinematic harmony, or maybe in Tarkosvky’s case, harmonious dissonance.

Janus Films’ 4K restoration of MIRROR is now available to rent via Lincoln Center’s Virtual Cinema.

Comments