Anika Pyle, like the rest of us, is consumed by uncertainties. To say she’s unsure about everything would probably be fair, but only insomuch as an entire generation is unsure of everything—the past, the future, the ability to control anything. Pyle has spent the better part of a decade exploring that uncertainty, and she’s quick to succinctly sum up some of that universal anxiety at the top of WILD RIVER, her first album under her own name: “Fear is the corners of yourself where you have brushed the tiny failures or abuses, or ‘cannots’ or ‘should nots’ or ‘never coulds,’ and let them collect dust until it’s time to clean house.”

It’s one of several dozen daggers she delivers across WILD RIVER, an album that mixes spoken word poetry with sparse, damning songwriting to create one of the most intimate portrayals of millennial existentialism to date. While its most intense narrative moments focus in on Pyle’s immediate internalizations on the recent loss of her father, the album as a whole, some of which was written in the wake of his passing and some of which predated it, represents an echoing cacophony of grief, anxiety, fear, and sometimes hope, reverberating in the moments after youth has finally passed you by.

Whether her name is familiar or not, Anika Pyle has been omnipresent in rock and DIY for the better part of a decade now, with the kind of resume that borders on prolific. She fronted the exuberant summer bummer band Chumped early in the 2010s, whose beloved fusion of explosive pop punk riffs and lustral hooks burned bright and fast before they called it quits in 2015. Quickly, she and drummer Dan Frelly formed Katie Ellen, a blend of the direct and cheeky rock the two had been creating with Chumped but one that often took on a plainer, in its best moments softer, edge to complement Pyle’s striking vocals and heartening, journeyman lyrics.

With sparser instrumentation and blunt prose, she uses WILD RIVER to focus herself while time marches ever onward. After ruminating on fear, she concludes the opening title track with a sliver of revealing hope: “I wanted to be the kind of lady / Twirls the room ’round her finger / Fun-loving, fun-loving, fun-loving / But I like to clean the kitchen at parties / I like to stay in on the weekends / I thought I’d be something special.” Hope, I need not remind you, is a dangerous thing.

—

Pyle, over the course of several different bands, labels, and sounds, has established herself as the rare generational voice whose body of work and career path have tandemly captured the experience and feeling of being a Millenial in real time. “Ultimately I’m just telling you my experience of being 24-to-31 through music,” Pyle says when we meet via Zoom. “if you’re having a similar experience I think you’re making the same connections I did.”

In working through this theory, of presenting Pyle’s own works as a microcosm of millennial adulthood, it becomes helpful that her career has unfolded in three clean acts. First came Chumped, a totem for quick, uncertain, reckless self-discovery. That earnest, tired vigor of being in your early 20s is not only the reason the band’s burnout energy resonates brilliantly today (it remains Pyle’s most known project), but ironically is the reason the band fizzled out. The lightning in a bottle is perhaps best summed up by Pyle herself on the TEENAGE RETIREMENT standout “Name That Thing,” where she smiles through it all, singing “And we drank and we talked shit and I was happy / Tried so desperately to hold on to the feeling / Of being young, and being sure, and being lucky / ’Cause I get down, and it’s so easy to feel nothing.”

“I’ve relished the chance to talk about the record because in doing that I’ve realized there is so much about my own grief process I had ignored and didn’t engage with.”

“Chumped did burn out really quickly. It imploded on itself…” Pyle says, before stopping herself. “Well, that’s the glass half-empty analysis. The glass half-full analysis is that we quit while we were ahead, and that’s true. But I kept going.”

Katie Ellen, which rose quickly from the ashes, was an honest continuation of Chumped’s volatile exploration of youth, with hints of that implosion resonating, but it also represented Pyle’s own bullish attempt to make a career in music. “The Katie Ellen experience probably feels very short for the listener but was very long for me. There was such a period of coming down.”

“Katie Ellen is such an interesting project because it’s very much the bridge from Chumped, which I felt was something that I couldn’t quite exactly be myself with— I was so much myself in certain ways, but I was 22 or 23 when it started, so it was this huge figuring out who you are period. Katie Ellen I really wanted to be who I was but I hadn’t done the internal processing to figure out “Who is she?” It was called Katie Ellen for a reason. I didn’t know who I was. I needed to figure my shit out under the guise of somebody else—a grand artistic ‘acting as if’ exercise.”

That feeling is in the music. As she describes it, there’s “a late 20s figuring-it-out quality” to Katie Ellen. “The emotional tone changes quite a bit,” she reflects. “But there’s a lot of power in those songs, probably demonstrated most in ‘Sad Girls Club’ which became sort of an anthem for me as a neurodivergent person who wanted to champion the power that you can have.“

It’s perhaps telling that the lingering chorus of “Sad Girls Club” laments that “sad girls don’t make good wives,” a blunter, more forceful and final sentiment than the “fun-loving” and kitchen-cleaning future Pyle sings about at the end of “Wild River.” Now recording under her own name, you can hear all of the journey simply in the timber of her voice—a wary, tired, but hopeful artist hoping to use music as a way to find one’s self and to reckon with the past. WILD RIVER feels like the tonal culmination of the shared experiences among people in their late 20s and early 30s—the loss of a parent or loved one, the realization that our hopes and desires have yet to materialize. “I’ve been practicing some radical acceptance in looking at each of these projects and accepting my multifaceted, creative output as patches on a quilt,” she offers.

—

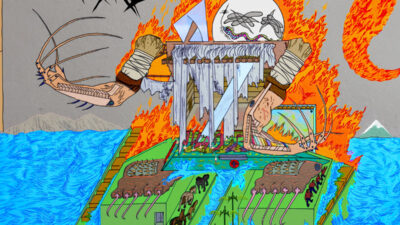

WILD RIVER is, even by her own lofty songwriting standards, a focused and cutting reexamination of self and grief. With its hushed atmosphere and sprinkled-in spoken word poetry, it’s a sonic reset for Pyle, but one set to match the emotional reckoning of the sudden loss of her father in October of 2019. As she puts in the liner notes, “Essentially, WILD RIVER is about learning to let go and move forward from grief steadfastly with love, despite the essentially cruel and random nature of the universe.”

Most of the songs on WILD RIVER were poems before they were songs, and knowing that you can hear that transformation in subsequent listens. Pyle shifts her soaring sharp observational wit into plainspoken contemplation of our existence, the poetry and song in constant conversation with one another. On closer “Windy City,” the two ideas collide into one, as Pyle delivers one final poem, stating “The relentless shame and utter idiocy of being human,” while she sings “no one knows me like you do” beneath. “We still seek joy and find it,” she concludes.

“I’m kinda here in the shadows like ‘hey, I still make music!’ and dealing with the reality of what my life was in the aftermath.”

Hearing Pyle delve into minute, complicated memories of her father and her own grief gives WILD RIVER a feeling of surreal urgency that’s difficult to describe, at once cutting yet refreshingly cathartic. On “Mexican Restaurant Where I Last Saw My Father,” Pyle lists off an assortment of memories before asking earnestly “When was the last time my father saw me cry?” On “Orange Flowers,” she lists his hopes and aspirations amidst contemplations of what comes next. Like Mount Eerie’s A CROW LOOKED AT ME or Nick Cave’s SKELETON TREE, WILD RIVER is among the best direct plunges into contemplating death and love as we’ve heard in recent years.

It’s dark, and there’s no getting around that, although Pyle is refreshingly self-aware of what a journey the album is as we discuss it. WILD RIVER coming out on the heels of a massive global pandemic means her words likely come as a source of strength, albeit under slightly more intense circumstances than the way Chumped and Katie Ellen’s words did. “I’ve relished the chance to talk about the record because in doing that I’ve realized there is so much about my own grief process I had ignored and didn’t engage with,” she says. “A part of the intention of making the record was holding space for people who had experienced the loss of a parent, or had experienced deep loss in general.”

—

WILD RIVER, by most metrics, feels like a success. Still, as a fan of Pyle’s, it’s hard to look at her brilliant career and not feel a sense of longing for both what Chumped could have been and for what Katie Ellen never quite became—perhaps that’s just another lesson in growth, allowing ourselves the retrospect to move forward. “It’s what happens in the aftermath of (when) a band that is constantly being tagged as the next big thing shoots itself in the foot,” Pyle says with a shrug. “Or what a loss of potential is. And I’m kinda here in the shadows like ‘Hey, I still make music!’ and dealing with the reality of what my life was in the aftermath… This all kind of forced me into making a solo record which was partially what I saw Katie Ellen as, but I wasn’t quite there yet.”

WILD RIVER isn’t just a sonic reset for Pyle, but also a career reset. I ask if that’s hard to reckon with. “From a capitalist standpoint, it lends itself to a lot of comparison of my peers,” she says. “It feels like I’m behind in some ways, even if that’s neither here nor there.”

“The other day Jake (Ewald) from Slaughter Beach, Dog said ‘every song you’ve ever written has gotten you to this point, even the ones you wrote when you were five years old,’” she recalls anecdotally. “‘Just because you might not have a salary from Anika Pyle doesn’t mean your work is not valid.’ And that was nice to hear, just from a peer who in some other circumstance I might be looking at and being like ‘Why am I not Jake from Slaughter Beach, Dog!’”

But the truth is Pyle is peerless, a songwriter who’s in a class all unto herself in DIY and indie rock. WILD RIVER only reaffirms her brilliance, the kind of in-the-moment record that very few artists have ever attempted, much less succeeded at, with such vividness and emotional depth. Sure it’s not a Slaughter Beach, Dog record, or even a Chumped record, but there’s an honesty to it that hopefully extends far beyond the broken economics of music industry success. That honesty, not just on WILD RIVER but across all of Pyle’s work, feels universal for a generation that’s constantly grieving and searching. I certainly believe that, and it sounds like Pyle does too.

In a SPIN profile tracking Chumped’s final shows, Pyle was quoted hypothesizing that “part of the process of closure on something is understanding the significance and validity of a specific record or time, and [making] peace with the fact that it changes.” It’s rewarding to hear WILD RIVER exist years later as a document of that sentiment, a way to make peace with change—accepting change is, after all, a generational life lesson. Hopefully Pyle will continue being the voice of this generation for years to come.

You can check out WILD RIVER over on Bandcamp, and tickets are available here to watch her perform songs from the record via live stream on 5/29 at 7 p.m. EST!

Photo Credit: Autumn Spadaro

Comments