There are a two things I want to be clear about from the very beginning:

The first is that I am not Ethel Cain. As a trans woman, I connect deeply to her work, but I also recognize the vast number of ways in which our lives could not be more different. Just for starters, I grew up and currently live in a suburb of Los Angeles, California, a city that Ethel Cain “will never be caught dead living in” according to her recent New York Times profile, preferring to rent out an abandoned church in the middle of nowhere in rural Indiana or Alabama.

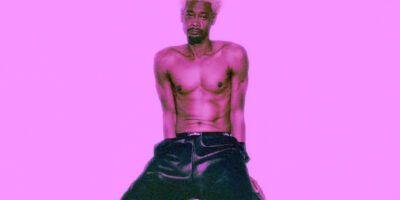

The second is that “Ethel Cain” is not just a pseudonym for Hayden Silas Anhedonia, who just released her debut full-length album, PREACHER’S DAUGHTER; Ethel Cain is half invented persona and half artistic vessel—a way for Hayden to create some separation between her real experiences and her art, while also imparting her memories, obsessions, fantasies, fears, hopes and dreams into this fictional character whose history runs parallel and intertwined with her own. I will try to be clear throughout this essay about when I am referring to the real person Hayden or the persona/character of Ethel, but the boundary between where one begins and the other ends is intentionally blurry, even for Hayden herself.

Ethel Cain is not just a fictional character standing in for Hayden—she represents something much deeper and more personal, seeing “Tremors of her past and the promise of her future” in this girl’s life story as it appeared in her own imagination. “That’s who I saw her as,” Hayden said in an interview with The Line of Best Fit, “and she spoke to me in a way that nothing else has ever spoken to me before.” But that doesn’t mean everything implied by the lyrics of PREACHER’S DAUGHTER is directly confessional of Hayden’s real life experiences. As she put it, “everything that happened to her is something that has happened to me, but I’ve kind of twisted it.”

—

So now with all that throat clearing out of the way, let me cut to the chase and tell you why I’m here writing about this album.

From the moment I first heard PREACHER’S DAUGHTER, it became the frontrunner for my album of the year—-the most rapturous reaction I’ve had to any piece of new music since Fiona Apple’s FETCH THE BOLT CUTTERS. I cannot stop listening to it, but much more importantly than that: this album struck an emotional chord within me that was so deep and so personal that I felt, for lack of a less corny word, seen. Understood. Loved—not by another person, but by the grace of God.

One thing that I should clarify, especially after that last part, is that I’m not really a religious person in either upbringing or practice. My parents were both raised Catholic, and even though I went to religious private schools for most of my young life up until high school, religion was hardly indoctrinated into me the way it was for someone like Ethel Cain. My parents gave up on taking us to church regularly somewhere around the age of 10, once their own parents grew too old to care that their grandchildren weren’t getting a proper Catholic education. It was a decision made because they didn’t want to get up early on Sundays more than it was any kind of definitive moral choice about whether I should be exposed to religion.

But despite that lack of hardcore instillation, there has always been a streak of spirtuality in myself that I’ve struggled to understand. I find myself returning to religious stories over and over and trying to reframe them to understand my own experiences. I’ve always been fascinated with art that grapples with the creator’s relationship with religion or faith, and themes and terminology from religion often end up in my own writing, even when I don’t initially intend on putting it there (my coming out letter was titled “Like Manna From Heaven”). I have almost never prayed in a formal “Dear God” kind of way. I don’t practice any religious teachings or wear a cross around my neck, and being trans and queer has given me a distrust and distaste for most formal organized religion, especially in this country. But every once and a while—especially when I am at my most vulnerable and desperate—I find myself calling out to a higher power. Cursing the cruelty of fate as if someone was listening, almost involuntarily pleading to a god that I don’t even think I believe in.

I’m lucky enough to be able to say that my friends and family have mostly been very accepting of my transition, but that was initially not the case for Hayden. Growing up in a small town of about 1,500 people in the panhandle of Florida, she describes the whole hyper-religious community treating her like a “satanic witch,” especially once she told her mother that she liked boys at 16 and was promptly sent to religious therapy. Although my own fears kept me from coming out about my gender and sexuality until later in life than was the case for her, deep down, on some level, I knew that my family would probably not abandon or abuse me for being myself—a luxury I kept in my back pocket that Hayden never had. As she puts it, the religious therapist she saw as a teenager after coming out to her mom as gay was “the first person to tell me I wasn’t going to hell. I don’t think she understood the assignment.”

Hayden says she is in a much better place with her family now than she was during that most turbulent period of her adolescence, but it’s impossible to miss the crushing weight of her hyper-religious past still weighing on her shoulders. It’s present in PREACHER’S DAUGHTER’s very first song, “Family Tree (Intro)” with lyrics like “The fate’s already fucked me sideways / Swinging by my neck from the family tree / He’ll laugh and say, ‘You know I raised you bеtter than this’ / Then leavе me hanging so they all can laugh at me.” There are words on the song “Hard Times” that speak to themes of childhood sexual assault, abuse disguised as love, and inherited generational trauma. She sings about being “Nine going on 18” in the first verse, and the song’s forlorn chorus repeats “I’m tired of you / Still tied to me / Too tired to move / Too tired to leave,” over and over.

It’s not hard to understand why, later in life, in the middle of a drug-induced breakdown not long before she finally came out as trans, she shaved her head and tried to tell herself the lie “I’m going to be a boy, and my family is going to love me, and I’m going to make them proud.” It didn’t stick.

—

The Southern gothic style to the storytelling and presentation of PREACHER’S DAUGHTER feels incredibly natural to Hayden, which makes all the sense in the world when you put the pieces of her story together. Of course, the woman who was deeply familiar with the tradition and repression of the religious south would learn to blend the writing of great Southern authors like Flannery O’Connor, with the darkness of the horror movies and true crime she was obsessed with as a teen—folding it all into these stories of “over-the-top American melodrama” and packaging it into a conveniently tumblr-ready aesthetic. But the homemade white dress and Jesus portrait on the wall from the album cover doesn’t feel like an internet put-on or Halloween costume, nor is her use of this iconography an attempt to paint this album a satirical, scathing rejection of American Christianity and the South.

Even as she expresses the rage, loneliness and suffocation of her youth under the thumb of systemic abuse, PREACHER’S DAUGHTER never feels like a complete rebuke of the vision of America that was instilled in her as a young child, nor a romanticization of it. Rather, it serves as an act of personal reclamation. It’s a way for her to chase the dreams she had as a young girl who didn’t yet know who she was one, and how to express herself to the world, even though she knows those dreams aren’t always necessarily good for her. As she puts it in the same interview with The Line Of Best Fit, Ethel Cain, “is the person I could see myself becoming, and she is the person I don’t want to be. She’s very much going down this fork in the road, and I need to go the other way.”

—

I could talk for many more paragraphs about Hayden’s fascinating personal history, as well as the growing lore of the worlds she creates in her storytelling as Ethel Cain (she has plans for screenplays and books in addition to her music). I could rant at length about how brilliantly the production toes the line between the slickness and grand scale of arena-ready pop rock (“American Teenager” is the best song FEARLESS/SPEAK NOW-era Taylor Swift never wrote) and the heaviness and dirge-like gloom that defines artists like Zola Jesus or Chelsea Wolfe (“Ptolomaea” is an absolute killer). I could gush about the towering guitar solo at the end of “House In Nebraska,” which is so anthemic and epic, yet distorted and muffled at the same time, that it sounds like Midwife performing the national anthem at the Super Bowl. I could rave about Ethel’s voice, a seemingly supernatural gift that is given full room to expand and fill every space she creates with these slow moving arrangements and atmospheres.

I could go on all day long about this album.

But the thing that moves me most about PREACHER’S DAUGHTER is the way it captures the intimacies of a particular kind of trans experience—one that I know all too well.

As a bisexual trans woman, trying to untangle myself and my sense of identity from the hateful, outdated, and frankly incorrect frameworks for gender and sexuality that were passed on to me has been a very difficult and complicated process that took many years, and, in truth, it’s something I am still working through. My upbringing was relatively tolerant and progessive by almost any metric, but, even still, just growing up as queer in America wherever you are, you absorb so much poison, so many lies designed to confused you and keep you from realizing that there are so many people who feel exactly like you do.

I always knew with some certainty that I was attracted to women, but I was also increasingly unable to avoid the fact that I was also attracted to men, and the harmful ideas the world had instilled in me were telling me that those two things couldn’t both be true, and that I should feel shame for feeling that way. That’s before even getting to my own gender, something I told myself for years that I shouldn’t even try to address because the only way for me to be desirable to others and to be accepted by the world was to be a man. This all made coming to terms with my sexuality that much harder, because, even after I accepted that there was nothing wrong being attracted to men and overcame my internalized homophobia, I still felt shame and discomfort around sexual experiences with men because I was still not being seen for who I really was, I was still afraid to be the woman I knew I was on the inside.

And so for those years of high school and college, I tried to tell myself the lie that I was going to be a boy and my family is going to love me and I’m going to make them proud. It didn’t stick.

—

It was a vulnerable experience to finally come out as trans, to share my story with the world about my gender and my long path to self-acceptance. But to this day, there is nothing that makes me feel as vulnerable and exposed as putting myself out there for male romantic attention. Whether it be daring to actually flirt with a boy I think is cute, or even just letting myself daydream of what it might be like if I had real boyfriend and not just some one-time hookup, my stomach begins churning with a mix of nervous butterflies and a deep seated sense of dread, as my worst internal monologue tells me “turn back now, it’s not like any boy will ever love you.”

This tortured dynamic—of wanting something you cannot help but want but being afraid to let yourself want it because of how Girls Like Us are usually treated—is a feeling that I know Hayden understands well, because this whole album is full of songwriting that speaks so clearly and directly to that experience. One of the most obvious examples is the eight minute power ballad “A House in Nebraska,” which tells the story of a pair of doomed lovers who “Found each other on a dirty mattress on the second floor” of the titular house in Nebraska, before he eventually leaves Ethel and their small town behind. Ethel still gets calls from the boy’s mom “Asking if she’s doing well,” but she’s devastated inside, abandoned by “The only person I was never scared to tell I hurt.” Despite that moment of intimacy and connection that they shared, that she thought was love, she was rejected for unspoken reasons that are implied by lyrics like “And it hurts to miss you / But it’s worse to know / That I’m the reason / You won’t come home.”

The heartbreak of that song is contrasted later in the album with “Gibson Girl,” the raunchy lead single that sounds like Ethel Cain’s answer to The Weeknd’s song “Initiation,” with the character of Ethel finding herself engaging in sex work for the man she’s run a way from home with earlier in the album. The song’s title comes from the artist Charles Gibson, whose pen and ink illustrations of the so-called “Gibson Girls” represented the idealized vision of feminine beauty in late 19th and early 20th century America, an example of how Ethel Cain’s music aims to repurpose the iconography of patriarchal American society to her own ends.

What I love so much about “Gibson Girl” is that it’s neither a moralistic cautionary tale about how “Sex Work = Bad and Dangeous,” nor does it fully romanticize the situation either. She feels empowered by being able to use her sexuality and the way men desire her to get what she wants, rather than being victimized by it. But it’s also clear that this lifestyle she’s been seduced by is probably not very healthy, and that these men do not have her best interests at heart. It’s an experience trans women who date men are all familiar with: you know that the man whose Grindr profile is labeled “DL [down low] seeking trans women”—the kind of guy who is embarrassed to be seen with you in public but wants to fetishize you in private—is not worthy of your affection. But sometimes you are so desperate to be intimate with someone, to have anyone at all desire you, that you settle for what you can get because you’ve been taught to think that’s what you deserve. It’s best captured by the line in the song “And if you hate me / Please don’t tell me / Just let the lights bleed / All over me.”

Ethel Cain isn’t the first or last heterosexual or bisexual trans woman to write about this conflicted set of feelings. Recent work, like Jamie Hood’s book HOW TO BE A GOOD GIRL, or Merry-Go-Round Magazine writer Jessie Herb’s essay in the LA Times “I’m a trans woman. And for once, I wasn’t fetishized,” are both great examples of other work that explores the heartbreak and self-lothing that often comes with trying to engage in relationships with cis men that often treat you as a disgusting monster, a depersonalized fetish object, or simply just not very desirable. But what PREACHER’S DAUGHTER achieves, which feels like a true miracle, is it manages to sneak this psychologically complex and incredibly specific depiction of trans womanhood into a remarkably broad and accessible album that can and should reach massive audiences beyond just trans people like myself.

—

A year or so since I first came out, I am growing increasingly confident in my identity and embracing and taking pride in my transness, but I can’t lie and say there haven’t been so many nights when I have desperately wished I could be a “normal girl,” even though I know how harmful it is to think in those cisnormative terms. When you essentially lose large swathes of your childhood committed to a game that you never wanted to play, it’s really hard not to look backward and regret time wasted, to not wish you had transitioned earlier, or wish you had been born into the stability and certainty of being cisgender in a society that still assumes and tries to enforce cis as the norm. I’m never going to get to pick out a dress and go to senior prom as myself. I’m never going to have so many of those stereotypical experiences and milestones of teenage girlhood that so many other girls take for granted. Instead, I had to watch from a distance as a male puberty changed my body in ways I hated, reinforcing the idea that those experiences would never and could never be mine.

The pull that this imaginary life of cisgender teenage womanhood has over me is one of the many things Ethel Cain is writing about on PREACHER’S DAUGHTER, using the fictional All-American girl she has created as a vehicle to continue the legacy of trans artists who “construct ideal versions of ourselves through our music, and then from there, we work our way towards it,” But, for as much as this album is about reclaiming the romanticized version of her womanhood she can’t help but want, it’s also about her recognizing the darkness of the world she came from, the psychological toll that living under a patriarchal society ruled by paranoid religious persecution takes on any woman, let alone a trans woman. As she put it, “I want her to be this girl, little girl, who’s trying to be a woman under this catastrophic weight of being the perfect daughter and friend and lover in this crazy country that is just chewing people up and spitting them out. I wanted her to be the poster child for what I feel is the casualty of being an All-American girl.” PREACHER’S DAUGHTER is an album about how cisnormative-heteronormative American society is killing you, but God it would still be really nice if you could have that comfort, stability, and safety those norms are meant to promise.

The album leans heavily into obvious tropes from all kinds of classic American storytelling—the BONNIE AND CLYDE esque lovers on the run, the small town girl with dreams of a bigger world who is ”Putting too much faith in the make-believe / And another high school football team.” A girl riding on the back of her man’s motorcycle, a pair of star-crossed lovers on a cross-country roadtrip through the West, hoping that once they reach the Pacific Ocean they might be able to find that thing they’re looking for. Knights on white horses, soul cleansing baptisms in the river. “It was me and you against the world / You my man and I your girl.”

None of this is subtle, and all of this capital A Americana is played to the cheap seats as big and soaring as possible—it opens herself up to being criticized for relying on cliches or biting off more than she could chew on her first record. It’s an admittedly tall task to make a 75-minute record about such weighty themes about God, and Love, and Sex, and Family, and Abuse, and America, all on your first ever full length project. But despite my obvious biases, she pulls it off remarkably well. For an album that spends much of its long runtime wading through the events of a dark and traumatic past, PREACHER’S DAUGHTER feels incredibly empowering, especially in the way she uses the same iconography and musical languages passed down from artists as iconic and essentially American as Bruce Springsteen and Dolly Parton to tell a story about transness that is simply never told on a scale this big in this country. Until now.

Trans women are told we aren’t allowed to have fairy tale endings or princess romances. That there are no handsome boys in pickup trucks waiting to ask us to the dance; we’re told the American Dream we’ve been sold our whole lives is a club that we’ll never be invited to. That’s what makes it so thrilling to hear a song like “American Teenager,” which takes those things and makes them feel possible and achievable for us, even if the song is a bittersweet fantasy of an adolescence Ethel didn’t actually get to have. Just thinking about the idea of a trans kid somewhere out there right now, particularly in one of the many states that have tried to implement horrific laws to outlaw healthcare for trans children, and imagining them listening to “American Teenager” as they dance around their room and feel a little bit less alone is enough to move me to tears. Even if you aren’t transgender, even if you didn’t pick up these nuances listening to this album, you can *feel* it in her voice how much it means to her to be reclaiming these narratives, to finally be the author of her story. And there’s no substitute for that kind of ineffable passion. It’s the thing that makes my hair stand on end every time I go back for another listen.

—

To briefly play devil’s advocate at the end of this sermon I’ve been on for the last few thousand words: I totally understand why some trans people will not be as into this album as I am, or why they might rub up against the idea of me anointing a skinny white woman with a remarkably cis-passing voice who sings a lot about heterosexual relationships and God as “the first true American transgender pop star”—as if the goal of trans art should be assimilation into the American status quo (not to mention the fact that Ethel vehemently denies the categorization of herself as pop artist at all). But I think Ethel Cain is far from your typical ideal assimilationist image of transfemininity or music stardom, and the way she honestly embraces the parts of her upbringing that are essential to who she is, while also rejecting those structures that repressed and abused her, feels incredibly unique and powerful to me.

As she said herself: “Everybody’s always been told that if you’re LGBT of some kind, you reject your small town, you move to a big city and completely change your whole life and live somewhere big, beautiful and vibrant. I love that for other people, but for me, I never really wanted to leave home, you know? I was always told that was what you had to do, so I tried to do it for a year—I moved an hour away from home, and it was too much. I wanted to be home. I love my family. I love the way I grew up. I love running around in mud puddles and being a little country tomboy. I never saw any trans narratives like that. I want to offer other options to trans girls and women who don’t really want to change too much—they just want to continue living the life they always have. I’m excited to see them living more truthfully to themselves, telling their stories about the world as it appears to them.”

I am not Ethel Cain. I’m not the preacher’s daughter. I don’t know what it’s like to grow up as a trans kid in an environment as suffocating and isolating as she did, nor have I experienced anything close to the same strained relationship with her family and generational cycles of abuse. But when I listen to PREACHER’S DAUGHTER and think back on the times when I felt lonely and lost in this world, I feel something so deep within my soul that putting it into words is difficult. I feel the companionship of knowing that the pain I feel is not my own. I feel the strength of knowing I can overcome my past and write my own future. I feel the magic of trans sisterhood, of knowing that every day there are more of us and that each time one of us finds the courage to be ourselves that there is more love and light in the world as a result. I feel the beauty of the natural world opening itself up to me, the Amber Waves of Grain and Purple Mountain Majesties removed from their patriotic context and allowed to stand for something much greater. I feel the universe telling me that the manmade structures of abuse and control designed to hurt me are no match for the love within my heart. I feel God, if that’s the word you want to use for it.

When Ethel Cain sings “What I wouldn’t give to be in church this Sunday” as a beautiful organ part kicks in on the penultimate track “Sun Bleached Flies,” there’s clearly nothing ironic or winking about the sentiment—she means every word, even though Ethel still doesn’t describe herself as religious and refers to her upbringing as cult-like. She can’t change who she is and where she came from, but through her art she can begin to see that story in a new light, and that newfound sense of peace she arrives at by the end of the album feels nothing short of revelatory.

That line is immediately cut by the harsh truth of the ones that follow it: “God loves you, but not enough to save you / So, baby girl, good luck taking care of yourself.” It’s a bittersweet reminder that the safety, community and stability meant to be offered by church pews is still a luxury not available to most trans people as religious groups and politicians increasingly target us with laws trying to drive us out of society and towards repression and self-loathing. It doesn’t mean salvation is out of reach—it just means we have to go looking for it in different places.

Comments