In 2009 Steven Porfiri was accused of never having played a video game before by someone on a GameFAQs message board, and the insult has haunted him ever since. Now, as the Senior Games Writer for Merry-Go-Round Magazine, he’s finally been given a platform to prove that not only has he been playing video games, he writes about them as well. I Played a Game Once is an inside look into what he is playing, and how it has any bearing whatsoever on our current moment. It’s basically like Carrie Bradshaw’s column but with more discussions about save-scumming.

When the first gameplay trailer for HUMANKIND dropped, the game seemed to be dogged by a single recurring question: “How is this not Civilization?” And this isn’t just snark on my part—the lead developers and creators also seemed concerned with addressing the Carthaginian War Elephant in the room. In an interview with ScreenRant, lead designer William Dyce explained that their advantage over the Civilization series was simply HUMANKIND’s newness, and that the team is able to “apply the design knowledge of today rather than having to essentially make room for decisions that were made in the 80s.”

While the games on the surface look markedly similar, is that just because they have a similar gameplay conceit? Both are nation-building strategy games that put the player in the role of a leader for a nascent real-world civilization that is looking to extend their reach to the world and beyond, pitting them against other leaders with similarly far-reaching dreams. And in order to do so, both games require strategic exploitation of similar yields, such as Food, Industry, Money, and Science, (HUMANKIND refers to them as FIMS). To the passive Steam scroller, there doesn’t seem to be many differences between either gameplay experience.

So in order to answer that question further, I played a couple of Amplitude’s previous 4x installments, ENDLESS LEGEND and ENDLESS SPACE 2. Good news for those that have played Amplitude games previously: there are a ton of echoes of these previous games present in HUMANKIND. Obviously certain things like the FIMS system are a rebranding to match the theme (can’t exactly use “Dust” as currency in a real-world civ-building game), and there are other facets of their games pulled into this one.

They did leave one fantasy faction in there, which was an interesting choice.

Booting up HUMANKIND for the very first time, the game asks if the player is familiar with 4x strategy games, giving them the option to say “no, not even kind of” or “yeah, I’ve played Civ but what’s your deal?” The player can also do their best Nick Offerman and declare that they know more about these games than the game itself, and opt for no hints or additional information. I, a noted dumbass, informed the game that I’d played Civilization before so I had a pretty clear idea on how the game would work. However, while I have played quite a bit of Civ, I’m also very, very bad at Civilization compared to the average fan.

While the game informed me of the numbers I must crunch and the yields to take into account when turning my outpost into a village, I felt myself flailing in my attempts to internalize all this information. The Civilization series makes similar use of helpful advisors, but there’s a running theme of accessibility throughout HUMANKIND, and it seems to be the way it wants to distinguish itself. Hovering over menu options provide brief descriptions on what each button does, production queues are laid out in a user-friendly format, and the game generally feels like it wants you to play it and have a sense of agency in doing so.

Another thing HUMANKIND’s developers want to do is to more accurately represent history, and allow the flow of the game to mimic the general ebb and flow of nations and cultures. The game has a credited Narrative Director, Jeff Spock, in order to help build systems that facilitate this. One of the most prominent ways they do so, and one of the most prominent differences between HUMANKIND and the Civilization series, is the approach to civilization transitions; with the latter, players are stuck with their leaders throughout the game, along with their special abilities, units, and buildings. This prompts a bit of strategy in terms of which leader will shine the most at which particular era. Sure Trajan’s Legion unit is good for early-game warfare and domination, but once everyone’s rolling around with tanks your gladius isn’t gonna help much. By contrast, a player in HUMANKIND starts out as a somewhat nomadic Neolithic tribe. This early stage sees players exploring the map, discovering wonders and resources, and dodging animals like bears and mammoths. Once a player leaves that era, they’re prompted to pick a new civilization or culture for each era they enter, allowing for much more flexible strategizing among players.

Yeah, yeah, once I invent trebuchets I got a couple spicy meatballs for you dorks.

In Civilization one leader means a very specific strategy, and oftentimes there are milestones a player has to hit in order to maintain their path to victory. A Science-focused Civ has to build specific Wonders when they become available and maintain their cities in a very specific way if they want to be the first to send out a probe to Alpha Centauri. But HUMANKIND allows for players to decide what they want to prioritize in a specific era, and provides specific buildings, units, and abilities to do so. My first choice was the aesthetically-inclined Olmecs who, in addition to boosting my territory-controlling Influence points, were also capable of building Olmec Heads to boost my food production and swiftly grow my cities. They also provided a powerful ranged unit, which I felt I might need at some point or another. The idea of changing your culture to suit your needs felt somewhat similar to the politics at play in other Amplitude games such as ENDLESS SPACE 2, where the rise of certain governmental factions can influence what sort of policies your government can pass.

Each culture in a particular era is optimized toward a specific playstyle. Certain cultures are optimized for war, others for building their population, others are for general expansion, and others for technological discoveries. These specialties will influence how a player gains the points necessary to advance to the next era. Accomplishing a feat in line with a nation or people’s archetype or affinity yields more fame. In turn, each of these feats earns the nation a Fame Star, and when seven are collected the nation advances. Thus it behooves the player to choose a nation that will help them gain an advantage over their opponents while building off of their previously established infrastructure. In order to begin building my Science resources I eventually selected the Korean Joseon culture, and attempted to build as much scientific infrastructure as I could. Once I switched to the territory-expanding Russians (not the Soviets, they came later), I figured it would help me sweep a competing civilization off the nearby continent.

This player went from the Mongols to the Huns, probably because of their shared advancement in the field of horse.

One of the things that will occasionally crop up in a 4x turn-based strategy game like Civilization is that around the late-mid game the action will kind of slow down. City planning gives way to managing production queues, the units you’ve built are just told to hang out wherever you put them for 500 years (unless they’re on auto-explore, but I’m too much of a simpleton to do that), and your enemies are simply monitored for movement. Indeed, this review process took much longer than I expected because I just did not want to sit through several turns of telling my halberdiers to chill out while I built an infrastructure queue in my capital city. However, in this regard it mimicked history very closely, as what was the start of World War I if not a bunch of leaders looking for a reason to try out all the sick murder tech they’d been building? And with that I was introduced to another major difference between Humankind and Civilization, which was how combat was handled.

An era of peace! All is quiet in Germany.

For players of games like ENDLESS LEGEND, the combat in HUMANKIND will feel very familiar. Multiple units can stack up to form one army which acts as a singular unit on the map. Upon entering conflict, players decide where to deploy their individual units and can make use of environmental modifiers such as high ground, forests, and swamps on land, as well as fogbanks and coral reefs during naval encounters. Displaying a striking fidelity to real-life combat, conflicts in HUMANKIND usually end after all units on one side have been destroyed. But if a player is engaged in combat they must not only stay alive, but protect the command post that spawns as well. In this way, if a player can’t retreat they can simply abandon their flag to the encroaching enemy. This mechanic adds another layer of strategy to gameplay, but having to send my units back to my command post after they’d been decimated felt obnoxious when I could simply dig in and defend.

Players can also initiate automatic combat, where the AI takes over immediately and it’s all done in an instant. Players should be wary of this option, however, as I tried it once and apparently during the instant battle took place the computer saw fit to bring in units from all over the map to take part in what I assumed was going to be a swift death for my poor Saboteur up against six or some Mongolian Archers. So with most of my units destroyed trying to save a rather unimportant unit (RIP but them’s the breaks), players should beware the AI’s decisions when it comes to managing their forces.

You don’t ever wanna let them get the high ground.

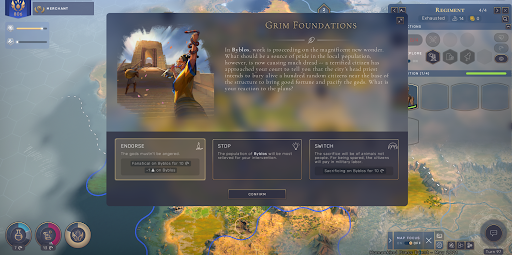

But if you’re a pacifist player, HUMANKIND does have another way to break up the monotony: National events will require your attention, and the choices the player makes alters the ideology of the nation. Certain choices will also have short-term buffs and penalties on their cities and their nation in general, and can even trigger other events down the road. These events will spring up depending on certain in-game milestones, such as meeting other nations, developing religious minorities, engaging in warfare, and pollution levels, so even if the horns of war are not sounding, there should be things that will require your attention.

This sense of micromanaging aspects of your empire is drawn from previous Amplitude games, just given a more true-to-history reworking. In addition to the relatively short-term effects on your people, your choices will also shape your ideology, and as your ideology develops it’ll also determine how other nations perceive you in-game. As one might imagine, the more aligned you are with another nation, the more likely they are to trust you and be less aggressive towards you.

Can’t a couple of pals bond over the shared tradition of mass sacrifice?

This is another example of the more fluid strategies inherent in HUMANKIND over Civilization; there are certain leaders in Civ that are notorious for specific behaviors (even outside of Ghandi’s predilection for nuclear war), and part of the strategy of Civ involves working around these idiosyncrasies. However, as time goes on in HUMANKIND, there’s a bit more incentive to follow the crowd in order to maintain friendly relations. Or not, if you do plan on steamrolling them.

The diplomacy mechanics are another aspect of HUMANKIND that the developers are particularly proud of. For them it also has to do with enhancing the game’s sense of narrative as it progresses. Dyce and Spock use a heist film as an analogy when it comes to the importance of building tension between players:

“…imagine a heist movie shot from the perspective of the bank manager. And so you follow this chap for an hour and a half and then at the end of the film, he realises there’s no money left in the vault. And that’s it. That’s kind of the strategy game experience where your neighbour builds tanks for an hour and a half and then suddenly declares war on you and just rolls over you. That happens quite a lot.”

In any given diplomacy screen between the player and an AI nation, there are a series of lists and options the player can use to track how that nation feels about them including their War Support, what grievances the nation has against the player (and vice versa), as well as their general personality, items they have to trade, and what deals the player can make with them.

According to the developers the idea was to make it so that diplomacy would be a way to prepare for this incoming bank heist, but in my experience it wasn’t so much statecraft as it was hand-waving away fist-waving leaders while promptly getting my ass handed to me by a verified Zergling Rush of Mongolian Archers any time I tried to encroach upon one of my neighbors. I never really grasped the complexities, I don’t think, but again I am not the most well-trained of players.

And while I am very hard on myself, one of the things I couldn’t help but notice while playing HUMANKIND was how light-hearted and friendly it was. In addition to describing the various civics enacted and other events, the game’s narrator would chime in to explain certain aspects of the game and comment on my progress as if to congratulate me for building 30 farm districts.

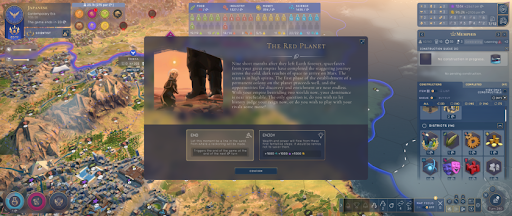

In HUMANKIND the Science victory involves establishing a colony on Mars, and you can either end the game this way or continue and go full Elon Musk.

But what truly grabbed me was after I had been narrowly defeated in a come-from-behind upset. Another player had gotten more Fame than me by turn 300, which in a regular game means it’s all over. Instead of chastising me for my miserable failure, HUMANKIND instead gave me a long list of my successes, including my contributions to science, and my dedication to preserving the environment (As the furthest advanced scientifically I was also the biggest polluter, and I didn’t wanna know what would happen as my pollution levels increased). But it was nice to not be told that no one would remember the works of my people as the bones of their final descendents crumbled into dust.

HUMANKIND prides itself on being a new take on the concept that Civilization pioneered. There are ways that it surpasses Civ and there are ways that it falls into the traps of its predecessor—it definitely has the feel of previous Amplitude 4X titles, and fans of those titles might find a warm familiarity in the way the game mechanics are laid out and the way strategies present themselves. For those who haven’t played an Amplitude title, HUMANKIND represents an alternate take on the historical nation-building concept. Don’t expect to have your mind necessarily blown, but its insistence on a more active narrative-weaving experience along with a fresh sense of optimism make HUMANKIND a fascinating new challenger in the space.

Comments