For those who cannot exist wholly in one world, liminal spaces become a home. This doesn’t really occur to me until I’m walking down the sidewalk with Fime’s Beto Brakmo and Maxine Garcia, thanking them for their time and saying goodbye. In the space of an hour-long conversation, the whole world has turned the color of aged honey, dripping and glowing across the sidewalks and facades of Highland Park, and it is suddenly obvious that this is the place where Fime’s music exists—the brief and bright in-between that halos them and everyone else. Their music is a part of the hours between the familiarity of day and the unknown of night, the dreamy cusp between sleep and waking, the border between states and countries and cultures. They are a band who has taken what is perpetually in motion and made it their home.

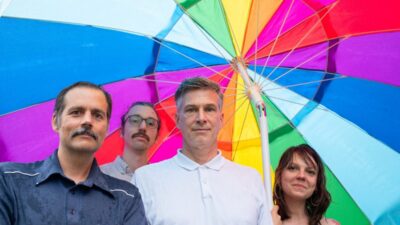

The sun has not begun to set when I first sit down with two of Fime’s three members. Brakmo (guitar/vocals) and Garcia (bass/vocals) have a quiet way about them—friendly, but with the reserve of people who consider what they’re saying before they speak. “We were all friends in high school,” Brakmo starts off telling me, Garcia adding “I knew [guitarist] Chase [Cook] in elementary school.” The trio were originally from the Bay Area, where Cook and Brakmo played in other people’s bands together, and when they all ended up in LA, it wasn’t long before they started their own band.

—

Their most recent release, last year’s EP SPRAWL, was written by the whole trio and packs the emotional weight of a full LP into five tracks. As the name suggests, the sound is expansive but cohesive, staying thematically narrow as it focuses on questions of identity and community. Like the best rock, it’s a work of existential honesty dressed up in the distortion and grunge of shoegaze to make something devastatingly earnest that swells inside you. This aural adrenaline is distilled to its purest form in the EP’s final track, “Boundless,” creating the exact feeling of a roller coaster beginning to drop while suspending it for five minutes and twenty-six seconds that somehow feel no longer than a single inhale.

“Every genre is pretty white, but indie rock is so white and hegemonic. I try not to think of it as a beauty contest, because a lot of the artists I really love fit that archetype, but it’s really hard to get out of the headspace that everything is a competition and that we’re in a beautiful, thin, white woman’s world.”

“Some songs are written together,” Brakmo says of their songwriting process, “but a lot of times, a person will come in with a riff or a verse—one component of a song—and the rest is written together.” Garcia nods. “We rely on each other.” This collaborative spirit is no surprise, given the endearing, High School Pals familiarity they’ve shown throughout our conversation. They have an easy banter, rarely interrupting but quick to build on the other’s ideas, and even quicker to talk each other up when they undersell themselves. It’s a connection that’s sonically palpable in SPRAWL, as they dig into the uncertainty of existing in an interzone.

The opening line of “Nogales”—the EP’s opening track, the title for which stems from two cities that exist on either side of the border between Sonora and Arizona—sets the tone for the rest of the EP: “Born divided / birth to amnesty.” This division of a self is echoed in the music as it switches from a hollowed-out melody to distorted chords, the two sounds fitting together seamlessly as Fime begins to take this liminal space and turn it into a complete world. When talking about this track, Brakmo says “it’s about being an immigrant to America and not quite fitting in to my Mexican side or my American side.” I can’t speak for everyone who comes from mixed heritage, but listening I found it to be a very familiar sentiment, and Nogales itself is the perfect metaphor. The absurdity of the same city in two countries, split by an invisible border. A place in two places. “Sometimes I just feel like this outlier,” Brakmo says. “Not quite Mexican enough to be Mexican, not quite American enough to be American.”

When I ask Garcia if she ever feels like an outsider too, she carefully nods. “I do. Every genre is pretty white, but indie rock is so white and hegemonic. I try not to think of it as a beauty contest, because a lot of the artists I really love fit that archetype, but […] it’s really hard to get out of the headspace that everything is a competition and that we’re in a beautiful, thin, white woman’s world.”

“But,” she adds with a smile, “making art with Beto helps a lot.”

It took years, but they’ve built strong friendships in LA that help as well, and it was this building of a community that informed the songs she wrote for SPRAWL. “[They] were inspired by my relationship to a city and understanding myself in a context of ‘How do I find a community? How do I feel like a part of something when everything and everyone is so individual?'”

SPRAWL is not an effort to answer these questions. (If such a thing is even possible.) Instead, it’s an EP that proves the importance of asking the questions. It gives voice to the insecurities and frustrations that everyone feels and turns the experience into something tangible.

“I don’t know how it happened, but we wrote songs that were very similar,” Garcia says with a small laugh as Brakmo chimes in. “It came together nicely. At the end we were all like, “Yeah—” and then in unison, “‘This makes sense.'” With a wry smile Garcia adds, “I guess we were all going through it at the same time.”

—

For such a cohesive EP, it’s funny that SPRAWL’s central theme is one of uncertainty, but it’s undeniably relevant to our time. “It’s big, unanswered questions,” Brakmo says. “It’s not like ‘here’s a narrative, here’s the beginning and the end.’ It’s expansive and stacked on itself.” Garcia’s track “Solo/Together” captures this feeling well, a six-eight shoegaze benediction in the form of answerless questions. “How do you feel without absolutely knowing? / How do you see without absolutely knowing?”

I begin to ask Garcia how she combats the inherent isolation of living in Los Angeles before becoming suddenly insecure that I might be the only one who’s felt this way, instead pivoting to ask if she even feels that isolation is inherent. There’s a laugh in her voice as she quickly responds, “No, it’s inherent.” She thinks for a moment, then tells me, “I kind of force myself to socialize, and a lot of times it’s really unnatural and I don’t want to, but then I never regret it. I’ve forced myself to realize that everyone feels this way. Everyone is nervous to go out, everyone is thinking ‘I don’t fit in here!’ and nobody feels a part of anything. So you can just go out and not have that pretense that you have to be cooler than you are.”

“The conversation when you’re coming back from a show. Like, we’re all a little exhausted, a little less uptight and tense… There’s just something magical about coming back from somewhere.”

“I think it’s important not to expect anything,” Brakmo adds. “Sometimes I’ll get nervous because I’m thinking I have to go see shows [to do] networking stuff but,” he lets out a small huff of laughter at his own anxiety and continues, “If none of that happens and I went to the show and they were a cool band? Then that was good enough.”

“Just to be there—just to be present—is a way to not be by yourself all the time. There’s energy transferred,” Garcia says. But it goes beyond that for Fime. “That’s been a big part of our ethos, especially for me and Beto, is we prioritize going to our friends’ shows and paying for their merch, and not being like, (here she perfectly mimics the patronizing cadence of every indie-rock dudebro’s mantra) ‘Can you guestlist me?'”

It’s an ethos that is a pillar of the indie rock and DIY community. Without supporting each other, there would be no community. And as the last few decades have seen rock fall out of the mainstream, the genre has become a place where outsiders can thrive, especially in a city like Los Angeles. “What’s exciting about the LA music scene right now [is that] there’s cool DIY venues that are having precedent over the bigger venues,” Brakmo tells me. “A band starting out can play a DIY venue and it has just as much prestige as somewhere like The Echo—which is really nice now. And it seems like the people going to those DIY shows are much more invested in going. There’s a huge difference between going to an established venue and paying some crazy fee versus paying five dollars that are supporting the band directly.”

There’s a youthfulness to the passion of DIY that reminds me of my teen years spent driving into Nashville to see local bands at the dives that allowed under-21s, and I’m not surprised when Brakmo tells me of his and Garcia’s early years spent driving into San Francisco for the same reason. “We were an hour-fifteen outside of San Francisco, so we always had to make the trek out there,” and, Garcia is quick to add, “It was worth it. To drive an hour for culture is worth it.” It’s a whole experience to make that drive, be at a show, and still somehow, the most memorable part can be the drive back. “The conversation when you’re coming back [from a show]—like, we’re all a little exhausted, a little less uptight and tense…” Brakmo trails off briefly—the struggle of trying to quantify something unquantifiable on his face. “There’s just something magical about coming back from somewhere.” It’s the kind of indefinable magic that Fime uses in their music, turning what was once a liminal space into a borderless, boundless expanse.

You can hear Fime’s SPRAWL over on Bandcamp.

Comments