A poor GOD OF WAR ripoff? A worthy trip through the Nine Circles of Hell? Or a messy adaptation of a literary classic? For the last several months, contributor Steven Porfiri has been playing, analyzing, and chatting with those involved in making one of the all-time greatest gaming flops: EA’s 2010 release DANTE’S INFERNO. Our exposé on the game breaks down exactly what made DANTE’S INFERNO one of the 2010s’ strangest relics

For some reason, I’ve always been fascinated by the various iterations of the classic medieval allegory THE DIVINE COMEDY by Dante Alighieri. Like many, I was particularly interested in the first and possibly most well-known of the three epics that make up THE DIVINE COMEDY, INFERNO. When I was around 14, I read an edition of Dante’s INFERNO that had been updated in the parlance of the ultra-modern new millennium, with illustrations that were a contemporary reimagining of Gustave Dore’s classic woodcuts. Later, I would read a more traditional translation that further baked in my interest. I read this particular version while away at a camp for students preparing to undergo the Catholic sacrament of Confirmation, and while Dante’s writings are not Catholic dogma, I think reading about the brutality inflicted upon those that strayed from the straight and narrow while hearing about the infinite love of God gave my high-school sense of reasoning a pounding.

I don’t remember when or where I first heard about the impending release of Visceral Games’ DANTE’S INFERNO; it might’ve been a YouTube video, a bus ad, an article in a gaming magazine—I really can’t recall. But I do know that the moment I became aware of EA and Visceral’s high-combo hack-n-slash gore-a-ganza, it became my mission to learn everything I could about it. Poring over the dev diaries, watching all the trailers I could find, learning all I could, I had to know more about this game. While I was instantly put off by Visceral’s reimagining of the poet Dante as a hulking death machine with an interesting idea of body modification (and even more interesting ideas regarding body armor), I was fascinated by the concept art and what the developers planned to bring to the table. Given the magnitude of the promotional campaign behind DANTE’S INFERNO, it was tough NOT to get even a little hyped.

Hell yeah, brother, it’s about to get theologically alle-GORE-ical up in here

Then the game came out, and despite making Yahtzee smash a wooden box and faking a Christian protest, the best the game could manage was a shrug and a solid “it’s fine” rating. Looking back on the Metacritic scores for DANTE’S INFERNO, it seemed equally matched between positive and middling reviews. I too was disappointed that it didn’t seem to match the infernal fury that was promised by the dev diaries and even a Superbowl ad.

I didn’t end up buying it when it was released. I didn’t have a lot of purchasing power as a kid/teenager; my parents never gave me an allowance apart from a few bucks for doing chores around the house (and that was only sometimes), and even then my parents had a pretty strict Anti-M video game policy (which lasted, as these things do, until one of my younger brothers brought home CALL OF DUTY: MODERN WARFARE 2), so me playing the game when it came out wasn’t exactly feasible. Plus the reviews seemed pretty negative, so, disappointed, I put DANTE’S INFERNO into the corner of my mind for the foreseeable future.

But after watching a booze-soaked Let’s Play of the game, I came to the realization that despite DANTE’S INFERNO being almost a decade old, I could probably purchase it if I wanted because I’m a damn adult now. I even had my old Xbox 360 that, despite all reason, was still chugging along. So 10 years, a trip to Florence, and a minor in Italian Studies later, I sat down to see for myself just what the Hell was up with DANTE’S INFERNO.

Part I: The Beginning of a Divine Comedy

BACKGROUND

Before I even began my descent, I looked into the background of the game, trying to develop a theory for what might’ve lead the developers in the decisions they’d made: DANTE’S INFERNO was slated to come out just before GOD OF WAR 3, and while Kratos was one of the primary demigods of gaming, the upcoming release was seen by all to be the final game in the series. So with the end near, EA was probably hoping to find a property that could hit all the buttons the God of War series did, filling the void it would leave before it even appeared.

Enter Jonathan Knight of Visceral Games, who stepped up with a brutal adaptation of Dante Alighieri’s THE DIVINE COMEDY. Visceral (which up until that point the studio was named EA Redwood Shores) was coming off of the (presumably) wild success of DEAD SPACE, so they knew how to use both gore and horror with an expert hand. Plus, THE DIVINE COMEDY was already a trilogy, and could be spread out over a number of years if need be. This is presumably when someone at EA said “HELL yeah” and giggled to themselves, greenlighting the project and setting in motion a hype campaign that would remain unrivaled in infamy until, well, DEAD SPACE 2.

Parents! They just don’t understand!

According to Steve Desilets, one of the creative leads on DANTE’S INFERNO, the story of the game’s genesis isn’t exactly as conspiratorial as I’d imagined: “The start of INFERNO going way back was Jonathan Knight,” Desilets told me, “who ended up being the [Executive Producer] and Creative Director on Inferno… he and I met on [THE SIMPSONS GAME] that Electronic Arts—we were making it at Electronic Arts Redwood Shores—we were just finishing up the Simpsons Game, and Jonathan had sort of just been ‘made,’ using mob terms, by EA as an EP.”

While working on THE SIMPSONS GAME, Desilets and Knight had developed a successful working partnership together. Desilets described Knight as the creative and business-oriented mind, and himself as a “master prototyper.” The duo discussed making a game together during the end of the development period of THE SIMPSONS GAME and informally decided to work on whatever it was that Knight could come up with after impressing the EA brass. After the eventual release of the game, Desilets took two weeks off while Knight set to work:

“By the time I came back he had come up with an idea, which was, ‘Let’s make a GOD OF WAR clone, but within the universe of Dante Alighieri.’ Dante’s INFERNO tested really well; he performed some research tests and Dante’s INFERNO registered really high as far as recognizability or Q Score of all the people asked. 77% of all the people from a very varied cross-section of people domestically had ever heard of Dante’s INFERNO; even if they didn’t even recognize the term ‘DIVINE COMEDY,’ even if they didn’t know who Dante Alighieri is, they’ve heard of Dante’s INFERNO. It had sort of saturated pop culture beyond its actual meaning. And so he’s like ‘Cool! It’s recognizable, and guess what, it’s totally free! And guess what, it’s about Hell, so that’s kinda cool. But guess what, it’s mostly about a guy walking and looking at things and passing out.’” <laughs> “So we’re gonna have to adjust it for, you know, an action audience.”

A brief tangent, but one that will become important later: for all of its critical success, DEAD SPACE wasn’t the commercial success one (read: me) would expect it to be. As the marketing for DEAD SPACE 2 would imply, horror isn’t the largest market one can appeal to, and according to Desilets, the sales numbers didn’t exactly justify a sequel. It wasn’t until Glen Schofield, former executive producer on DEAD SPACE, became the studio manager at Visceral that the ball got rolling again on a sequel. The critical success of the game and the placement of its former EP were helpful, but it was actually the commercial success of DANTE’S INFERNO that kept the lights on at Visceral and gave the studio the capital to make the sequel at all, in a testament to the complicated inner workings of game development.

GAME DEV TYCOON tried to warn us, but we were fools to not heed its warnings

As someone who has read and studied Dante slightly more than normally, one of the things I picked up on early in-game, as well as even in the dev diaries, was that the team did demonstrate an understanding of the poem and its basic outline and structure; Dante the character is a man who finds himself lost in a highly allegorical dark forest with no clear idea how to proceed forward. As he wanders, he meets the Greek poet Virgil, who informs him that while Dante is still alive, Virgil has been instructed to guide him through the afterlife by his first love, Beatrice, in order to help him find his path. While traveling through Hell, Dante learns what befalls those who are forsaken by God and how their punishments are doled out, and it’s all pretty metal.

But, as it turned out, not metal enough for the brutal landscape of the early 2010s, or at least for the action game that Visceral wanted to make. One of the first things one notices about the cover art for DANTE’S INFERNO is Dante himself. In order to justify the brutal hackin’, slashin’, button-mashin’ gameplay, developers gave Dante a makeover and backstory that would fit the tone and conceit of the game. Dante the Poet became Dante the Crusader. While this portrait of Dante Alighieri stands in stark contrast to historical records, he did in fact have a military history, fighting for the papal-supporting Guelphs in the Tuscan civil war between the Guelphs and Ghibellines.

While taking liberties with biographies isn’t the biggest of deals, one of the most striking aspects of this Dante isn’t just his massive, hulking physique and bizarre sense of body modification; it’s how much he looks like someone else. Looking at Dante’s design already calls forth echoes of Kratos, but knowing that the game was largely a clone of GOD OF WAR really brings it into clarity. A hulking, angry man with an iconic weapon seems to describe most protagonists, but a concerningly unarmored man with a shock of red to spice up his color scheme? Hmmm…

As atonement for his sins, Dante has decided that the best way to show he’s sorry is to sew a tapestry in the shape of a cross into his chest and stomach. This acts as something of an exposition device, as throughout the game Dante’s sins are elaborated on in specially-animated segments reminiscent of the art from the HELLBOY comics, and these sins seem to be woven into the tapestry on Dante’s skin. It’s sort of like the end of INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS where Christoph Waltz has a swastika carved into his forehead so that everyone recognizes him as a Nazi, and so similarly does Dante choose to have the cruciform bear his sins. From the outset it’s made blindingly clear that this isn’t your Italian professor’s Dante, but it might be strikingly similar to her Inferno.

“Stupido sexy Dante… ”

GAMEPLAY

One of the biggest criticisms lobbed at the game is how much it plays like a God of War title, and you’ll be excited to learn that that not only is this criticism completely warranted, but is, in fact, the much sought-after goal of the Visceral team. According to Desilets, Jonathan Knight “picked the God of War genre because this is what EPs do at EA: they pick a license, or something that provides a lot of narrative structure —‘cause making new IP from scratch takes years to do and write—and no game company like EA is gonna take the time or have interest in that. Not that often, anyway.”

The franchise that best fit the mold for the game, according to Desilets, was God of War, because it had the attributes that Knight wanted in his game. “…It taps into the mythos, y’know. It’s about mythological beings, just like Hell would be. It’s action based, brutal.” As Desilets put it, the team “did some synthesis between IP and genre” in order to provide a structure for the game, and they would eventually bring on some of the key level and combat designers from GOD OF WAR (2005) to fine tune the combat. “The first thing [Knight] said,” Desilets says, “was ‘we’re going to clone GOD OF WAR.’”

“I always thought of it like Jack Skellington ripping open a teddy bear trying to find the meaning of Christmas,” Desilets told me, laughing and giving his best Danny Elfman impression. “And that’s when we found out things like the light attack chain in GOD OF WAR 1 is 155 beats per minute. I noticed there’s a musicality to it. A year later, when we brought in Eric [Williams], who was the lead designer on GOD OF WAR 1 and 2 and former Street Fighter Tournament champion, he verified, ‘Yes, this is the way we do it.’ He verified that everything they do has a musicality, it has a rhythm, it’s all about rhythm and controlling space and your volumes of attack.”

The ensuing hours upon hours spent watching God of War footage frame-by-frame in order to understand the rhythm of the game’s combat and what made it feel so good were not spent in vain. Combat in DANTE’S INFERNO feels good, but as someone who has played GOD OF WAR, it can’t help but feel derivative, like I’ve done it before in a different life. Even though the game gives Dante a ranged attack via holy blasts fired from Beatrice’s crucifix, the overall tempo still feels like GOD OF WAR. This similarity extends into a lot of the emotional elements of the game, as well. While chaining together heavy and light attacks to rack up massive combos is a feature of many other games, there’s something about a rage-filled, deeply-flawed, and incredibly jacked man journeying towards a vague sense of redemption that rings more of God of War than, say, Devil May Cry.

As Dante kills things he collects souls from them that act as currency to level up Dante’s abilities in duel-branching pseudo-morality trees. Improving “Unholy” abilities gives Dante new and improved scythe attacks as well as strengthens the magic he’s able to use. Leveling up your “Holy” abilities likewise unlocks new and improved versions of Dante’s Holy Cross attacks, and can unlock Holy Magic abilities. These branches also require experience in order to unlock new levels of abilities, and these are gained by either absolving or damning enemies in combat. Grabbing certain enemies with the scythe presents this choice, and a quicktime event executes it and the demon in question. On other enemies this can only be done after beating them into submission.

Don’t worry, you’ll get these opportunities a lot

In order to further upgrade your abilities, the player will occasionally stumble upon a shade that has managed to escape torment for the time being. These are all historical figures mentioned specifically in INFERNO because of their various sins, and if the player idles a bit nearby one of these shades, they’ll recount the events that led to their damnation. It’s a neat little bit of information that the player can choose to pay attention to before grabbing the poor soul by the throat and deciding their fate. If the player chooses to damn them, they’ll be brutally executed, making them, I don’t know, super duper dead?

If the player takes pity on them (maybe people shouldn’t be sentenced to eternal damnation for being into butt stuff?), they can absolve their sins and send them to Heaven, which makes things really messy theologically speaking. But in order to usher this soul to Paradise, players have to play the most annoying minigame since BIOSHOCK decided that hacking vending machines required rearranging plumbing. Players have to hit the correct face button when a sin orb (??) passes over it to absolve it, I suppose. Eventually the orbs speed up and hitting a button when there’s nothing there decreases the amount of souls/experience you get, but like in BIOSHOCK, it’s one of the most frustrating things someone could put in an action game by bringing the action to a screeching halt. By collecting three Beatrice Stones somewhat early in the game, the player can bypass this minigame altogether, which is nice, but it also is part of a trend where DANTE’S INFERNO gives players the ability to cut out entire game mechanics. This trend, while seemingly damning of the game’s development, is most likely due to the fraught mandates issued by EA (more on that later).

Listen, buddy, you can absolve Pontius Pilate if you want, but it’s gonna be a real kick in the dick

Ultimately, none of these mechanics do anything to influence the game’s story or how it unfolds. The Unholy/Holy paths only serve to enhance a player’s preferred playstyle and little else. Neither has any effect on the overall story, nor does it matter how many people are redeemed versus how many are damned other than special achievements for doing one or the other on specific characters.

Also present in the game are relics, which augment Dante’s abilities in various ways. Things like Frederick II’s Ring, Ciacco’s Bile, Eyes of St. Lucia, and other baubles named after various sinners and figures are featured in the game because they’re specifically mentioned in the original poem (with the exception of St. Lucia, who was only added to foreshadow the Trials of St. Lucia DLC). One of these, the Rage of Farinata, allows the player to automatically destroy fountains, which is how health and mana are recovered, caches of souls are found, and where more relics are hidden (again, the presence of unlockable items that cut out entire mechanics does not bode well for the rest of the game). Players can equip these relics in combinations that best suit their playstyle, be it high-damaging scythe attacks or, and I’m not kidding, not being hurt by the shitting attacks of the Glutton enemies.

A more useful tool than one would think!

The inclusion of a branching morality/tech tree without any sort of impact, as well as the inclusion of the Beatrice Stones that allowed players to skip the Absolution minigame, and the relics that allow players to skip other mechanics, could probably be chalked up to the fact that the game’s development cycle was cut in half shortly after it was greenlit. “…[after] we were told we have 36 months for development,” Desilets recalls, “a week later Nick Earl came by with some bad news: ‘Actually you’re gonna get 18 months.’ So we went from 36 months to 18 months and I was like ‘Holy shit!’ But we still have to deliver everything we promised.” Needless to say, going from a three-year planning and development runway to a year-and-a-half can really put a damper on some of your most ambitious plans.

Desilets recalls that among the designs scrapped was an entire mechanic that would only be accessible had a player chosen to gone down the Unholy path, unlocking the ability to construct turrets from discarded infernal materials. “…you’d find just discarded piles of flesh because the flesh is stripped off the souls when they come in, the souls go on to be tortured, and the flesh is repurposed to build chairs and clothes and cities and stuff like that,” Desilets explained.

This vaguely Ed Gein aesthetic is a reference to the writings of Wayne Barlow, who provided much of the concept art for DANTE’S INFERNO, as well as concept art for numerous Guillermo del Toro films and even the creatures in AVATAR. Barlow is also a writer, and wrote several volumes describing his interpretation of Hell, and the development team for DANTE’S INFERNO, including Desilets, were interested in incorporating some of these elements into the game.

“You can find these [piles of flesh] and reanimate them with a series of different mechanics. You could have a flesh golem, or a big fleshy turret that would fire, like, acid. So [Dante would] have these strategic elements around the map that he could convert, if he’s on that path, to help him fight battles” said Desilets, referring to the option to have Dante gain more Unholy abilities. “So it was really a tactical/strategic mechanic that’d be placed around the world that if you took that path, you’d have that advantage. It’d at least give you a reason to go back and play a second time on that path so you can use those mounds of flesh that you can’t use if you’re righteous. So that was something I wanted to put in very badly because I thought it would add an interesting choice and a continued repercussion of past choices that would give you a sense of buyer’s remorse to motivate you to replay the game.”

In academic discussions of THE DIVINE COMEDY, scholars often use the names “Dante the Poet” and “Dante the Pilgrim” when distinguishing between which Dante they’re discussing. Dante the Poet is the author of INFERNO, PURGATORIO, PARADISO, whose decisions on who is in what part of the afterlife and why give him a stern, authoritative, and powerful feel. Dante the Pilgrim is the character within the narrative, who is constantly overcome with emotion and pity for the souls he finds, and needs to be taught the justice of the afterlife.

This duality is not at all dissimilar to the way in which DANTE’S INFERNO was made. EA demanded an intense, action-packed game within a tight deadline, and Visceral did their best to comply while also trying to fit their boundless imaginations within its confines to deliver exactly what EA wanted. Consider it Dante the Publisher and Dante the Developer. The halving of the game’s development timeline would lead to many scrapped mechanics and forced redesigns throughout the game, leading to something that can best be described as a shade of Desilets and Knight’s original vision.

Desilets seemed to imply that the 18-month development schedule was daunting, to say the least; “I woulda shit my pants, but we did it! 18 months from start to finish, we got that game out.” Being on the shorter edge of game development for what was more or less a new IP for EA and still managing to ship the game was a point of pride for him that wasn’t without its hardships. “…despite the fact you all pulled together and you shipped a game in record time that made enough money to keep the lights on it doesn’t mean that you had a good time doing it,” he said. “But we still have to deliver everything we promised.”

Part II: Development Hell

STORY

While Dante’s original INFERNO could be accurately described as a poem about a guy looking at stuff and passing out, DANTE’S INFERNO needed to be a much grander, engaging narrative in order to not only appeal to gaming audiences of 2010, but also to be seen as a worthy competitor to the God of War franchise. Speaking with Steve Desilets, Lead Designer on the game, it seemed as though the idea of going to Hell to rescue Beatrice was one of the first things the team, or at least Executive Producer Jonathan Knight, had decided on. Regarding Knight’s motivations for going with this concept, Desilets sums up the attitude in the conference room. “‘Let’s take Dante’s INFERNO: it’s available, it’s recognizable, Hell’s kinda cool. And who doesn’t wanna go and save the princess from Hell? It’s like Mario, but Hell.’”

Beatrice Portinari was the epicenter of all things pure for the historical Dante Alighieri (despite meeting her, like, twice over a nine-year span and ultimately marrying someone else), so why would this Beatrice be in Hell? Perhaps she made a deal with the devil, a deal that hinges on the good behavior of Dante the Crusader, which doesn’t seem like the safest bet. Maybe something like staying true to Beatrice while he’s away. Away where? Why, war of course! When we meet Dante he’s returning home from the Third Crusade, specifically the city of Acre, where he apparently messed up so bad he decided to atone for his sins by sewing a tapestry representing the major ones into his own skin (how the tapestry was made is unclear). What we learn then is that during a riot in Acre he was literally stabbed to Death, who appeared to Dante to inform him that because of his sins he was condemned to Hell. Dante, laboring under the impression that his service in the Holy Land would absolve him of sin, somehow kills Death out of pure indignation and takes Death’s scythe as his own.

To revisit this image, how does Death die? Is everything like that FAMILY GUY episode now?

It’s not metal enough that Beatrice is taken to Hell, so when Dante returns home to Florence, he finds her and his father brutally murdered. Well, his father is brutally murdered, but the game somehow manages to give Beatrice’s corpse this weird sexy undertone. Other than the sword sticking straight out of her stomach, she’s lying on the ground with her breast exposed like “Oh, Dante, didn’t see you there, I’m just being dead and demure.” Her spirit appears to Dante (and, as spirits don’t wear clothes, completely nude) but is quickly whisked away by Lucifer.

From there the backstory is told in flashbacks until it catches up with the beginning of the actual game as Dante’s past transgressions are revealed according to the circle of Hell he advances to. In Lust, the player learns that because Dante banged one of the hostage women of Acre after she offered her body for her and her brother’s freedom, he doomed Beatrice to get sexed up by Lucifer on entirely out-of-place four-poster beds. In Gluttony, we learn Dante… drank a lot, I guess. That’s not much of a revelation, so in the middle of the level (apropos of nothing, as I’ll discuss later) we find out that the brother of the woman Dante slept with was actually her husband, and, being royally pissed about Dante cucking him, guessed where the crusader lived and traveled from what is modern-day Israel to Florence so he could rub out his entire family. Truly, we are playing the wrong person’s game.

“This spaghetti sauce left on my wife… A Tuscan, Florentine in particular…”

Amidst all of this, there’s a weird moment where Dante asks Lucifer, who is showing him these visions, where the shades of the people he’s killed are. Lucifer responds that this isn’t “their Hell”—it’s Dante’s. Whether this is foreshadowing the end of the game or teasing a reveal in a future game where various aspects of the Abrahamic religions are questioned is unclear, but it adds a tinge of mystery to the game that I can’t decide if I like or not.

In the circle of Greed, we find out that Dante’s father was a huge asshole, and by Wrath we’re already aware that Dante’s been a bit of a prick himself, so when we find out that he killed some dudes he shouldn’t have, it’s not the most shocking reveal, nor is it in Heresy, where we find out that he fucked up because he was so sure he’d be absolved by fighting in the Crusades. It’s not until Violence that we find out that not only did Dante’s mother kill herself to escape the cruelty of Dante’s father, but that the riot from the beginning of the game was instigated by Dante and crew murdering the entire city of Acre, an actual historical event known as the Massacre at Ayyadieh. Historically this was understood to have been ordered by Richard I, aka King Richard the Lionheart, who in-game hangs Beatrice’s brother and Dante’s friend Francesco after he takes the rap for it.

During this time Beatrice, seeing that there is no way to Go Home, decides to instead Go Big and consume the Forbidden Fruit, aka pomegranate seeds. This seems like a shout-out to the myth of Hades and Persephone, another story where a maiden was taken to Hell and forced to become the queen of the underworld after eating pomegranate seeds. To celebrate her new role as Lucifer’s queen, there’s a moment where Beatrice intensely tongue-kisses him while Lucifer looks at Dante over her shoulder, and boy oh boy is it weird.

Hmm

This happens between Wrath and Violence, so by the time we hit Fraud, Dante’s backstory is complete, and there’s really no reason for Beatrice to stick around other than to help fill that out. After the frustratingly repetitive Fraud level, Dante tells Beatrice how bad he feels about the whole thing, causing her to revert back to her “pure form.” She’s retrieved by an angel who has some more vague lines about Dante’s destiny and his journey and its divine nature and whisks her away to what we presume is Paradise.

But there’s one more circle to go, Treachery, where Lucifer is theoretically hanging out. Once Dante confronts him, we learn that even though Beatrice’s kidnapping was what set off the whole game, and indeed has served as the true animus of the plot, she never even mattered to begin with! Cue sinister violins, because Lucifer’s whole plan was for Dante to free him from Hell by severing the Chains of Judecca, which the player has been doing almost mindlessly during every transition from one level to the next.

When the player first finds one of these chains blocking their path, they don’t really know what it is, why it’s there, or what it’s chained to. They do know that it’s flashing intermittently, and that can only mean one thing in a video game. So the player smashes them, the chain dramatically falls into the abyss, and they can hear Lucifer laughing from nowhere. I think the player, at this point, is supposed to assume that it’s your standard evil villain laughter, mocking Dante’s attempts at progress, but it’s not until the final boss fight that it’s revealed that the chains were holding Lucifer in Hell, and now that there’s no chains, it’s on.

Satan, seen here just waiting to get this shit over with

After the fight, Lucifer tells Dante that even if he’s defeated, Dante still can’t leave because he actually got super killed back in Acre, and as a sinner he’s doomed to remain in Hell. But Dante has a trick of his own up his sleeve, revealing that the souls he accumulated in Hell give him the ability to absolve himself, somehow. It’s not thoroughly explained why the souls the player has used to buff up Dante’s abilities are also able to pull him out of Hell and reseal Lucifer, but that’s exactly what they do. Dante then passes through the center of the world and ends up across the shore from Mount Purgatory. Because Dante has been redeemed or something the tapestry on his chest is now withered and charred, so he easily removes it and heads toward the mountain, spiritually renewed and ready for a sequel. However, for whatever reason, the remains of the tapestry transform into a snake that slithers away as Lucifer laughs in the distance.

Clearly there is a DANTE’S INFERNO II being teed up, as the game doesn’t exactly state that the mountain is Purgatory, but if you’re familiar with THE DIVINE COMEDY, then you’re aware of the structure of the story and can recognize the landmarks. According to Desilets, this was for a few reasons, and interestingly enough, many of the reasons that DANTE’S INFERNO didn’t receive a sequel were the opposite of why DEAD SPACE did.

CHARACTERS

As mentioned previously, one of the most prominent reimaginings is the conception of Dante Alighieri, going from literal poet laureate to battle-hardened former Crusader and proto-tattooer. There’s not much that separates him from Kratos, the battle-hardened, former military commander who also bears the curse of what he’s done on his skin. This definitely doesn’t help the “Like God of War But” comparison, and part of why his backstory and characterization is so “ho-hum” is where it could’ve come from and gone. The decision to make Dante a Crusader is understandable, but as mentioned before, he was historically a military man who fought for the Guelphs against the incursion of the Holy Roman Empire-supporting Ghibellines, notably serving in the battle of Campaldino, a battle which effectively turned the tide of that conflict in Tuscany.

But a more prominent facet of Dante as contemporaries understand him is his exile from Florence. Following the Guelph-Ghibelline conflict, Dante’s Guelphs began fighting amongst themselves and two more factions formed. While both sides initially supported the Pope, Dante and the White Guelphs wanted a restrained papacy when it came to Florentine affairs, and the Black Guelphs wanted Rome to have more influence. This led to some real GAME OF THRONES skullduggery, back when “the game of thrones” was also known as “the events of Tuesday afternoon.”

The Black Guelphs would eventually seize power, framing Dante for corruption. Dante denied the charges and refused to cooperate, causing him to be exiled from Florence forever. While the game mentions the conflict in the form of one of the Damned shades that Dante can either absolve or condemn, it’s a blink-and-you-miss-it reference, as this character is specifically mentioned in the poem. Dante’s exile was a huge deal, and is mentioned in several stanzas of THE DIVINE COMEDY, so it would stand to serve as an excellent source of backstory. It’s unfortunate that GAME OF THRONES only really picked up a few years after the game’s release, as the fascination around sword-and-shield soap operas could’ve really resulted in a very different direction for the character.

As a character, video game Dante is a loud, angry guy with a physically impractical weapon (the developers had a model made and tried to hold it, to no avail), and for a dude that cheated on his lover, surprisingly dedicated. As his entire backstory is laid out for the player, the game seems to blame most of these traits on how he was raised by his father, who admittedly does try to kill him at some point.

“A big part of Dante’s quest is redemption, or it least it should’ve been,” according to Desilets. When asked if there was anything cut out of DANTE’S INFERNO that he would’ve loved to include, Desilets specifically mentioned he would’ve liked a moment in the middle of the game that focuses more on Dante’s need for redemption. “We give him this great moment for him to REALLY convince us he’s realized what he’s done and how sorry he is, and it’s just so two-dimensional.” Desilets here is referring to the moment right before Beatrice gives herself to Lucifer, right before The Tonguing. “Nearly every man who has been in a relationship with another human being has probably fucked up in one way or another and can probably relate to knowing you fucked up and how you need to make things better. I felt like that would’ve been the more mature choice and, quite honestly, would’ve given Dante a little more dimension than it did.”

Even Dante’s final absolution comes across as largely self-serving, as he brandishes the souls he’s been collecting as a weapon that seals Lucifer back into Hell and allows him to pass through to Purgatory. As mentioned before there’s only one ending no matter what tech tree you choose to put the majority of points into or how many sinners you save or damn. In a game that ostensibly features morality, the lack of any consequences due to player choice really makes the themes ring a little hollow.

In-game footage of Dante passing into Purgatory despite remaining a huge asshole

While the Greek poet Virgil is a presence in the game, his is a very muted figure in sharp contrast to the Virgil in the original text. While in both the game and the poem Virgil functions as Dante’s guide, lost is the powerful, authoritative Virgil of the text that often tells the inhabitants of Hell to fuck off and leave Dante alone just cause he’s still alive. In DANTE’S INFERNO, most of Virgil’s conversations are optional and players can ignore him if they so choose. But by doing so, they miss out on additional relics that can only be gained by listening to Virgil’s counsel, many of which are word-for-word lines from the text. There’s a moment in the Dark Forest prequel DLC where Beatrice mentions that she’s sent Virgil to guide Dante, but for all the effect Virgil has on the plot or even gameplay, he may as well not be there altogether.

Other than being a convenient pair of boobs for a game wanting a Mature rating, Beatrice doesn’t have much of a purpose in the game; Lucifer might as well have stolen Dante’s favorite weight set to get him to come galumphing into Hell. Indeed, the treatment of Beatrice would come under fire by Dante scholars, including Teodolinda Barolini, a Columbia professor and former president of the Dante Society of America, who has been quoted as saying “She is not to be saved by him, she is saving him. That’s the whole point!” It’s also weirdly unclear in the game what the relationship status is between Dante and Beatrice. He clearly loves her a great deal and they’re referred to as lovers, but are they married? Going steady? Domestic partnership? Who’s to say?

There’s a lot to-do during the game about the purity of Beatrice as well; after she eats the Forbidden Fruit, Lucifer shouts about the “incorruptible becoming corrupted” before she transforms into her Queen of Hell form. But watching this made me think that if Beatrice was at all as pure as she’s being made out to be, she probably wouldn’t have made a deal with the devil to begin with? I always felt that that was a big no-no among Christians, no matter what the era or setting.

The only other “character” in the game is Lucifer. While there are others, they function more as bosses, and the player doesn’t really hear from them or care about their relationship to Dante until he’s about to eviscerate them horribly. We don’t really care about Cleopatra’s motivations in Lust, but we are concerned that her nipples are mouths from which demon babies emerge. As the Emperor of Dis and Literally the Devil, Lucifer traditionally hasn’t needed much motivation other than “this will really fuck some people up.” Such is the case in DANTE’S INFERNO, where he subtly boasts during the final boss fight that once he’s free he can regain his place in Paradise and destroy everything good in the universe, whatever that means.

Lucifer as the player encounters him at the end of the game has a couple different forms, aside from the shadowy specter that calls you a nerd and fingers your girlfriend while telling your shitty dad to kill you. The first is the traditional Satan described in INFERNO, a colossus with three faces and three pairs of bat wings that beat an icy wind. The second is a smaller version that inexplicably has a MASSIVE swinging penis. No one in the game really mentions it, Dante doesn’t look at it like, “Christ, look at that hog,” and it’s not used to attack him, but it’s just a foot-long dong swingin’ in the icy wind, which makes its size even more impressive.

I took the opportunity to bring this up with Steve Desilets, who helped design numerous characters, and scripted boss fights. According to Desilets, the idea to give Lucifer a five-dollar footlong came from Jonathan Knight. Knight “was attributing ‘masculinity’ with ‘evil’, and wanted to use Lucifer’s male genitalia to reinforce this concept.” From Desilets’ account, it doesn’t seem like this was one of the most well-received decisions, and said the team itself found the idea “snicker-inducing.” He further went on to relate a story where some developers had used the “ribbon tech,” presumably used to dictate the physics of the tapestry flowing from Dante, to make it so that Lucifer’s penis dragged 12 feet behind him at all times. Again, very impressive given the climate of the circle of Treachery.

Here’s a link to the NSFW character model, but due to the site’s aversion to swingin’ hogs here’s the Beelzeboss character from TENACIOUS D AND THE PICK OF DESTINY

DESIGN

If there’s anything we learned from games like AGONY, it’s that sometimes when developers go all-in on horrifying brutality, it tends to fall quite a bit short. It’s the level design equivalent of being 17 and groping pasta in the dark while someone goes “And these are the witch’s BrAaAiinsss!!” Such is the case with DANTE’S INFERNO, where the sense of creative brutality and horror was the main facet of the game’s hype campaign. To be fair, there are parts where there’s a real sense of creativity and morbid glee that can be felt in some of the designs, even if they are a little mid-2000s X-TREME by today’s tastes. Some of the most intriguing designs sprang from the work of artist Wayne Barlow, who did concept art for DANTE’S INFERNO as well as AVATAR, HELLBOY, and PACIFIC RIM. Steve Desilets lauds Barlow’s contributions to the game’s art, in particular mentioning Barlow’s punch-ups to the Glutton enemy, which Desilets describes as a “shit demon” and “that big, fat, gross, hands-were-teeth character.” Though certain aspects like turning the boatman Charon into an actual Boat Man can be a little jarring, certain levels like the city of Dis and parts of the circle of Greed make for solid experiences. Even parts of Gluttony are at least varied and different even if it took the one fart joke in INFERNO as permission to base the whole level around it.

“But first each pressed his tongue / between his teeth as signal for their leader / And he had made a trumpet of his ass.” -Inferno, Canto 21

What’s heart-wrenching about these levels is that many of the better designs end so quickly. Part of it is due to the many different circles, levels, and pockets of punishment present in the original INFERNO, so much so that developing each into their own coherent level could be a daunting task (a daunting inferno, if you will). This was more than likely exacerbated by the game’s development schedule being cut in half from three years to a year-and-a-half, and even explains a lot of character choices.

Regardless of the circumstances, there’s a feeling of “is that it?” when progressing through each level, and playing through it you can kind of feel a point in each level where it seems like the developers said, “Well, that’s enough of that shit, let’s get something else in there.” One particular moment that stands out is in Gluttony, where the player is brought to what feels like an alternate dimension within Hell known as The Hall of Gluttons. Here, they’re introduced to the tank-like Glutton enemy and Lucifer just kinda calls Dante a punk bitch for a little while. The transition from the organic, almost Geiger-esque biology of Gluttony to the stark, stone puzzle segment that is the Hall of Gluttons is incredibly jarring, and almost unfair.

In the original INFERNO, the cantos of Fraud contain some of the most brutal and horrifying imagery of the whole poem, as Dante and Virgil travel through the pockets of the Malebolge and examine the various aspects of fraudulent behavior; thieves are chased by and transformed into snakes, fortune-tellers have their heads snapped backwards, and sowers of discord are mutilated and split asunder by demons. In DANTE’S INFERNO, the circle of Fraud is just a series of arena battles with a specific combat objective like staying in the air for eight seconds, winning before your automatically-depleting health meter runs out, or defeating all enemies in a single combo. It’s even more of a letdown than the Hall of Gluttons example, because immediately preceding this circle is Violence, which contains the Phlegython, the river of boiling blood, the Forest of the Suicides, and the Burning Sands of the Sodomites—all showstoppers in their own right.

The level design in Fraud was also a common point of interest in many reviews, most of which were dissatisfied by the shift in gameplay that made it appear the designers had run out of steam. I would find out later that they had instead run out of time, and after speaking with Desilets, I learned that Fraud was another facet of the game that fell victim to Visceral’s development schedule, rent in half like a sower of discord in the Malebolge. There’s a lot of imagery to be adapted, and while they were mostly incredibly brief, each pocket was at least present. Each circle of the Malebolge is punctuated and differentiated by a statue representing the individual punishment, but the ensuing fights don’t have anything to do with the themes, other than the taunts that the newly-crowned Queen of Hell Beatrice shouts at Dante.

All of her taunts are stuff like “YOU’RE a prostitute… cause you suck!”

The inclusion of plot-inessential nods to the original poem were particularly bittersweet for me. As I said, INFERNO is a much denser text than its page count belies, and the effort to fit every bit of imagery and allegory into a video game adaptation that translates each one into a useful and enjoyable mechanic or concept must have been quite a task—some were better than others. In Greed, there’s a puzzle where a statue shoots light onto piles of dust, turning them into bejeweled platforms of varying heights. Once the puzzle is solved and the player passes the statue, there’s a mysterious voice saying “Pape Satan, pape Satan, aleppe.” This statue is identified as Plutus, the god of wealth, who in INFERNO serves as the demonic guard to the circle of Greed. Upon seeing Dante and Virgil approach, Plutus utters that phrase as a sort of warning (the actual meaning of the phrase is still hotly contested among academics). This part of the game happens right in the middle of Greed, but other than the puzzle there’s no real interaction with Plutus. Other elements, like the minotaur and the centaurs in Violence and Geryon in Fraud, are similarly represented as statues that don’t have much purpose other than a callback to the text. Again, I would rather they be in there as nods than not in at all, but it’s interesting to note their existence in-game as a sign that the developers were familiar with the text, but for whatever reason couldn’t fit each mythical figure in the adaptation.

As a teenager who hadn’t yet played the game, I assumed that one of the main reasons the game didn’t do well critically owed to the fact that the game didn’t properly translate many of the aspects of the original work. But looking deeper into the development of the game and its contents, it seems that the developers had more of a handle on the source material than I previously gave them credit for. As a stark example, the presentation of Cerberus as a horrifying worm creature that emerges from the depths of some great horrible face (and not the traditional three-headed dog) seems like a creative liberty designed for X-treme sensibilities. However, as one reviewer noted, the text does not say that this Cerberus is a dog, but Virgil does describe the creature (in-game and in-text) as “that great worm.” And as discussed, there were plenty of references and inclusions from the text that made it into the game, so it wasn’t lack of reading comprehension that hobbled the game’s eventual critical reception.

If you point a gun at my head, I’ll admit that DANTE’S INFERNO is an alright game, but there’s something about cutting the development process of anything by half that hampers the quality of the final product. When I asked Desilets about the things he wished had made the final cut, more engaging gameplay concepts and mechanics that were to be integrated into the story were mentioned. Yet as the team’s deadline approached, last-minute adjustments turned fair compromises into hasty revisions.

Desilets remains resolutely proud of the way the team had developed the combat, and mentioned that he felt bad for the combat developers once the reviews began coming out, specifically mentioning Lead Combat Designer Vince Napoli’s contributions to the game’s combat mechanics, working around the clock to push the boundaries of combat and make sure that it felt good. Napoli (who would go on to work on the combat for 2018’s GOD OF WAR and is now at Crystal Dynamics) and his team were reportedly disappointed with the reviews:

“…when [the combat team] saw 73 [percent] critiques, those critiques were 73 not because combat felt bad, they had done their job, they had done really, really well and it wasn’t easy. So they saw 73 and they were like ‘Fuck!’ But even on a 73 some of [the reviews] would say ‘combat feels okay. Combat feels good.’ So I felt bad for everyone that worked on combat… you can’t really spend too much time feeling bad about that.”

I had made peace with the choice to cloak the adaptation of Alighieri’s poem in an action aesthetic early on in my playthrough of DANTE’S INFERNO, so not too much of it bothered me (other than the general fridging of Beatrice and sidelining of Virgil). To be fair, it’s a lot easier to adapt INFERNO into an action game in a year-and-a-half after taking such liberties with the story, and in that sense making those changes seems to be an acceptable amount of risk if one wants to appeal to a consumer base that loves gory hack n’ slash games, isn’t entirely familiar with original text, and isn’t concerned with thinking about it too much.

The real legacy of DANTE’S INFERNO is the way Visceral and EA attempted to make up for the potential loss by pouring loads of capital into what could be very politely described as a relentlessly aggressive marketing campaign. When asked, Desilets denied having much of a role in the campaign, due to heavy development tasks, but acknowledged its notoriety: “I’ll say this,” he told me, “it was creative.”

Part III: Divine Judgment

RECEPTION

DANTE’S INFERNO, at the time, seemed to largely scratch a collection of itches, and given the enormous hype campaign to promote it, it damn well should’ve. The first month of its release it sold around 240,000 copies for the Xbox 360 and 220,000 for the PS3. In comparison, the highly-anticipated GOD OF WAR 3 sold over a million copies in the first month of its release, so while DANTE’S INFERNO was more widely available, with combined sales it failed to make half the numbers of the game it sought to emulate. However, the original GOD OF WAR sold around the same numbers upon its release in 2005. Critically speaking DANTE’S INFERNO was received with mixed reviews and failed to garner the “universal acclaim” achieved by the God of War Franchise. According to Metacritic it had almost as many middling reviews as it did positive, with a small percentage of reviews outright panning it. Most critics latched onto the gameplay as a solid reiteration of combo slashers, that while fun, didn’t exactly bring anything new and worthwhile to the table. Obsessed as I was with learning everything I could about the game and its development, when it didn’t exactly blow up the spot I mostly wrote it off.

Critics were split on the game’s imagining of Hell and its relationship to the original poem. While most applauded level design aspects such as the way the developers employed moving textures of sinners trapped within the walls of Hell and the rivers of blood, many of those critics bemoaned the repetitive nature of the design and felt that the last third of the game lacked all the imagination that initially hooked them. While in today’s post-AGONY paradigm it’s easy to write off edgelord aesthetics as simply that, these reviews demonstrate the paradox of designing games that include realizations of places that are supposed to be horrible enough to scare people onto the straight and narrow path, which is that a lot of people might just dismiss them for trying too hard. Unfortunately for these developers, these visualizations might not age particularly well, whether over the years or over the hours of gameplay.

Most AGONY reviewers concurred that after the 50th toothed-vagina-face demon going “ooga booga” from atop a pile of entrails, they had a pretty good idea what the game was trying to do.

Some of the more damning reviews touched on the spaghetti-in-the-dark aspects of the game, but the more positive ones took it in stride along with the similarity of the gameplay mechanics to God of War, actually listing those similarities as points in the game’s favor. Nick Chester of Destructoid said in the site’s review that if any piece of art is going to emulate another in the way that DANTE’S INFERNO does that they should do as well as their influence, if not better, and that “In that respect, DANTE’S INFERNO impresses.” More often than not the game is referred to as a God of War “clone,” but seems to still be pretty fun. And to be fair to the video game journalistic scene of 2010, despite what my experiences with the game were, being fun should be a pretty big component of what a game does.

As it turns out, “Like God of War but meh” was not enough of a ringing endorsement for EA to put their full weight behind a PURGATORIO and PARADISO follow-up to begin with, but the ensuing upheaval of the team meant that Dante would be stuck in Limbo forever.

PROMOTION

The hype campaign for DANTE’S INFERNO is about as legendary and devilish as the poem itself, and as others have commented, warrants an entire PR and advertising case study on its own. Electronic Arts hired Wieden + Kennedy—an ad agency that at the time had a hankering for viral marketing and in 2010 would win AdWeek’s Agency of the Year award—to push the game for around $20,000 per month. You may remember the commercial during the Super Bowl, which was a 30-second clip of Dante plunging into Hell that featured no in-game footage, but did feature Bill Withers’ “Ain’t No Sunshine.” There was also a DANTE’S INFERNO Facebook game which offered freemium-style gameplay to recreate the major points and locations of the game. But the firm also had concocted a series of stunts and contests for each level of Hell that were deployed at various points prior to the game’s release.

This got me hyped beyond all reason

After the game was announced, the content aggregate site Digg announced that they’d partnered up with EA to advertise DANTE’S INFERNO by offering up their own source code as ad space. Lo and behold that when the code for the site was viewed, there was an ASCII art image of one of the demonic unbaptized babies that would be found in the Limbo level of the game. Curious minds would soon find that several video game journalism outlets also had their source code renovated under their noses to promote the game. Passwords found in the code would lead to downloads of concept art, wallpaper, and other digital freebies from Visceral and EA. This would prove to be the most benign and least obnoxious stage of the campaign.

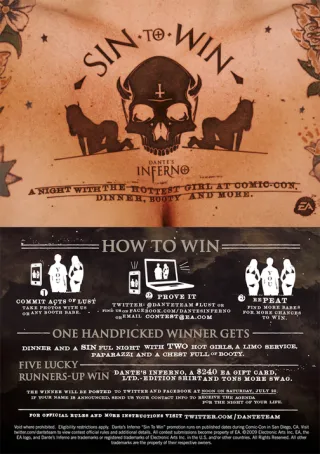

At San Diego Comic-Con fans were encouraged to “commit acts of lust” and record them on camera. While this sounds more like an entirely different convention, fans were told to take pictures with various “booth babes” at the convention and either post the pictures to Twitter with a special hashtag, or email them to a specific email address. Fans were encouraged to do this as much as possible in order to maximize their chances of winning a “sinful” night out with two models including dinner and a limo, ending the night with them in a penthouse that EA and W+K made sure to mention included a jacuzzi. This winner would also receive a chest full of limited-edition swag. In one of the best cases of ironic justice, a writer from the site Gaymer won the prize for posing next to a male booth “babe.” The writer would go on to write a scathing open letter about the contest. “While I’m not sure if it was intentional or not,” he wrote, “this stunt projected a view of your target demographic as lustful heterosexual males, when in reality a larger and larger portion of the gaming population are women and LGBT people.”

Here’s a slightly better picture with clearer depiction of the contest rules, but I thought it was important to note the integration of a woman’s chest and cleavage into the ad copy

This wasn’t the only bit of shenanigans EA would get up to at a major convention. At E3 that year, protesters picketed outside the convention center condemning DANTE’S INFERNO and EA (“EA = ELECTRONIC ANTICHRIST” read an actual sign). It would later come out that these protesters were paid by Wieden + Kennedy to drum up controversy surrounding the game. In another twist of irony, the news of the fake protest caused an actual protest amongst Christian bloggers, particularly from the premiere source of video game criticism that pledged fealty to the Holy See at the time, CatholicVideoGamers. “Gamers of all varieties will buy this product if it’s, well, actually a good game,” they wrote, “So instead of engaging in a shamelessly anti-Christian stunt to promote your poor excuse of a product, maybe you ought to work on making this game, you know, something better than a blatant GOD OF WAR rip-off and make it, ya know, something worthwhile?” Oof!

To be fair, this is selling fundamentalist Christians kinda short in terms of protest slogans

Gluttony would end up being a little trickier, as sending food and drink to people is just kinda nice. In order to get around this, the marketing company would end up sending a cake in the shape of various limbs to the editor of Joystiq. But a simple leg cake would not do for a company named Visceral, oh no; the cake was also made entirely of meat. Kind of like how the Glutton enemies would consume shades and Dante, EA decided it’d be devilishly funny to offer Joystiq the same opportunity.

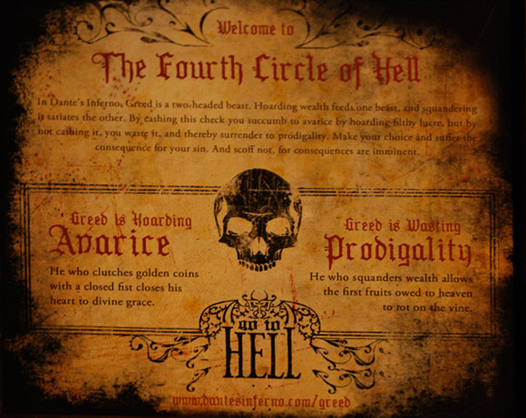

Starting around September 2009 checks were mailed out to several prominent gaming critics. Foreboding checks for $200 were sent in equally foreboding boxes with the explanation that they can either cash the check and be greedy, or refuse to spend the checks and be wasteful. In the game as in the original poem, these were distinctions among those condemned to the circle of Greed. “The checks are as real as the consequences that follow” the boxes warned. It’s unknown how many outlets spent the checks or how many ignored them, but certain outlets made a point of mentioning that their checks were donated to charity, while others like Kotaku posted videos of them lighting their checks on fire. These outlets also leveled criticism regarding the practice of openly bribing gaming journalists for better reviews as well as the eye-rolling aplomb the stunt presented itself with.

“Hoarding Filthy Lucre” sounds like something I have to pay a woman in a leather suit to say to me

In another critic-targeting stunt, EA sent out small wooden boxes to another group of critics, including Zero Punctuation’s Ben “Yahtzee” Croshaw. The box, when opened, would play Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up,” because 2009 was a much simpler time and RickRolling was still fucking hilarious. The box, when closed, would not stop playing the music. The only way to stop it was to destroy the box using the included hammer and safety glasses. Once destroyed they would find a note inside condemning them for giving into the sin of Wrath.

The late 2000s, as one may recall, was when companies began to experiment with motion controls, most notably brought on by the advent of the Nintendo Wii. One day an announcement was made regarding a new way to get kids interested in The Lord and give families a way to go to church every day: MASS: WE PRAY was a game that among other things featured a massive crucifix-shaped motion-controller and offered all the thrills and salvation of your standard Catholic Mass, complete with kneeling, sprinkling holy water, and rosary-ing, probably (it’s been a while for me). This made the rounds on gaming outlets and content aggregates like Digg until it was revealed a few days later that the whole thing was made up by who else, but EA. In fact, if anyone tried to go to the website to purchase the game they’d be shown a short clip of them being denounced as a heretic and then sent to a site to either pre-order DANTE’S INFERNO or use an app to “damn” their friends via Facebook. I get what they were trying to do but if MASS: WE PRAY was “denounced” as Heresy, it has very concerning implications for the rash of Biblical games released in the early ‘90s, though I have a feeling this isn’t official Catholic dogma.

Pictured: The absolute depths of Sin

Finally a commercial began airing on various networks promising men (specifically men) tips on how to start dating or win the affections of their friends’ girlfriends. The company known as “Hawk Panther” would lead men to a page that would very suddenly tell them that for attempting to steal the significant other of their best friends they were guilty of the sin of Treachery, then encouraged them to buy the game.

There were also pretty benign things such as the Facebook game, as well as a series of developer diaries where those that worked on the game would discuss each level and what went into bringing it to life. But it was by far the stunts that aroused the most ire, and experts are still split on whether it worked. The sense of unwarranted severity and general crassness of the activations would put a bad taste in the mouth of reviewers and critics, who in articles would mention the game’s lack of imaginative gameplay and stark similarity to God of War. On the other hand, the game was being talked about and generating buzz, and as the saying goes, bad press is better than no press at all. Indeed, in an interview with Ars Technica, Jonathan Knight would reiterate that the similarities to any other game were a sign that the developers had done their job in making a game that was ultimately satisfying and fun to play, a point that Steve Desilets echoed. Knight also defended the the game’s creative liberties with the source material by giving anecdotal evidence of gamers, intrigued by the brutal nature of the game, that were picking up more and more copies of the original poem. But again, ultimately no matter how popular the game was, no matter which outlet was covering the controversy, it comes once again down to the fact that this article is only describing DANTE’S INFERNO, and not PURGATORIO or PARADISO.

AFTERMATH

After the game’s initial release it was supported by a few DLC releases. Many of these were additional costumes, including one giving Dante his “classical poet” appearance and another that gave Dante a massive afro and leisure suit entitled “Disco Inferno.” These also came with additional souls and a few new relics depending on which pack one bought. Visceral also released new story content, a prologue known as “The Dark Forest,” alluding to the forest Dante navigates before reaching Hell in the original poem. The DLC has Dante navigating the titular forest on his way from Acre to Florence, attempting to intercept his assassin from Acre before he can get back to Dante’s villa and kill his family. The Dark Forest introduced two new enemy types and incorporated the allegorical beasts that Dante encounters in the original Inferno: a lion, a leopard, and a wolf. It’s essentially another level and introduces the new enemies, as well as the concept of Virgil being sent by Beatrice. The DLC mentions St. Lucia as well, in preparation for the next major DLC release.

Most Biblical contemporaries refer to her as St. Lucy but it really doesn’t have the same “Giant Scythe and Angel Wings” vibe

“The Trials of St. Lucia” gave players the ability to create arena levels similar to that of the Fraud level. The DLC shipped with about 20 “story” missions built by the developers that introduced players to the mechanics available to them. Players could select the arena they wanted, and could then load it up with monsters from the game in order to challenge other players online. In order to preserve the 60 frames-per-second rate the developers worked to maintain, players could only introduce a certain amount of enemies and traps to the arena at a time, in order to avoid bogging down the processors with 50 unbaptized babies.

Visceral also developed a brand-new playable character for Trials, the titular St. Lucia. Reimagined as an avenging angel with a scythe and Dante’s guardian angel, developers worked to develop an entirely new feel for her. Faster than Dante, she would float around the level, and could even glide for short distances for more aerial attack opportunities. She was also given limited optic blasts, because having no eyes means room for laser eyes. Her main drawback was that she had less health than Dante, and it would deplete faster than his.

The game found a decent audience, which proved to be a double-edged sword for the community, as for every meticulously thought-out and considered arena, there would be five levels with one enemy. This was because there were quite a few achievements in DANTE’S INFERNO that were attached to positive performances in these levels, and so naturally there developed a market of incredibly simple challenges designed to help players go platinum for the game. This interest would last until around the end of 2016, as players would take to forums to ask why they couldn’t access the servers. Explanations of poor server quality gave way to the news that the servers had officially been taken offline, ruining the platinum potentials of newcomers. All-in-all the DLC lasted around six years, which would prove to be a longer lifespan than the sequel to INFERNO, which as we know never made it out of development.

If you still need someone to give you a five-star rating on your arena I’ve got some bad news

According to Steve Desilets’ account, towards the end of the development process the INFERNO team was growing restless. Creative decisions were questioned, infighting was common, and the hours the team worked grew later and later. After the game shipped, most of the team started work on PURGATORIO, and by Desilets’ reckoning, it lasted for about six months.

“[The team] had some novel mechanics in mind, they had some amazing art tech being developed by this guy, Eric Holden, who was the main art tech wizard that we had on INFERNO. He was a guy who could make magic on the screen happen so fast. There was like, living vines that you could control, all these really cool ideas that they were starting to push out, but PURGATORIO was ripped to pieces from the inside-out.”

The internal divisions seemed to come with the team, and as a result, no one wanted the creative lead position for the game, and by Desilets’ account those that were interested were too inexperienced to lead. With himself off the project and Jonathan Knight taking a restrained leadership role, Desilets began to develop another prototype with Knight. Known as BIG WAR, it was a third-person shooter with customizable action-figure characters, described as TOY STORY mixed with GEARS OF WAR. The prototype would eventually grow to impress the highest levels of EA management with its sheer playability and fun, and it was eventually decided that with the PURGATORIO team fraying and the less-than-enthused critical reception for INFERNO, resources would be better put to use developing BIG WAR.

Then, in late 2010, Jonathan Knight left EA, leaving Desilets as project lead. Desilets would also leave soon thereafter, both to develop games on Facebook. Development continued for about two years afterward until it was finally shut down. Desilets attributes this to the game aiming too high for the gaming industry, as BIG WAR would’ve been the first multiplayer game able to be played across any platform simultaneously. But, as recent dust-ups with Sony have shown, the industry still isn’t quite ready for such a paradigm shift.

Pictured: Sony

As it would turn out, the greatest victim in the story of DANTE’S INFERNO other than the grades of a couple-hundred English Lit students would be Visceral itself. With PURGATORIO finally laid to rest, Visceral refocused and put out DEAD SPACE 2 in 2011, and then DEAD SPACE 3 in 2013, around the time when BIG WAR was also purportedly shelved. While each release received generally favorable reviews, they also each developed a trend of decreased sales. Later that year, Electronic Arts’ VP, Patrick Soderlund, would say in an interview that they would not be working on a DEAD SPACE 4.

After two more action shooters in the form of BATTLEFIELD 3: ENDGAME and ARMY OF TWO: THE DEVIL’S CARTEL, Visceral would release BATTLEFIELD HARDLINE, an outlier in the Battlefield franchise with a heist-style cops-and-robbers gameplay rather than massive military deathmatches. The game didn’t exactly flop (similar to the performance of DANTE’S INFERNO), but it would prove to be the final game Visceral released before the studio closed with the cancellation of Project Ragtag. This might be familiar to some, as Ragtag was going to essentially be HARDLINE but set in the Star Wars universe, following Disney’s acquisition of Lucasarts and EA’s release of STAR WARS BATTLEFRONT in 2015. Players would’ve been able to control several different characters planning and executing various heists, which would take place soon after STAR WARS IV: A NEW HOPE.

Unfortunately for Ragtag, conflicts over the game’s “lofty” goals, creative direction, linear vs. nonlinear storyline, and many other issues caused EA to cease development at Visceral, and the studio was shut down later in 2017. Development was then reportedly shifted to EA studios in Vancouver, but as recently as this year, there have been reports that Project Ragtag is officially no more.

Great disturbance, thousand voices crying out in anguish, yadda yadda

After leaving Visceral in 2010, Steve Desilets worked with various studios to develop games for Facebook, including Zynga. He cites the allure of these games being that they’re simple, fun games with a broad audience that are less stressful to develop than the hardcore action-based titles he’d worked on previously. After working at Amazon Studios in Seattle, Desilets left to start his own independent gaming company, Sockeye Studios, where he currently works.

Jonathan Knight now works as a studio head at WB Games’ San Francisco division. His most recent gaming credits consist of the WESTWORLD mobile game that was discontinued after being sued by Bethesda Softworks for bearing a striking similarity in gameplay and art design to their mobile game FALLOUT SHELTER. He’s also been recently credited as a writer for a series of impressive fan-made shorts that envision Dante’s return, DANTE’S REDEMPTION, created by developer Tal Peleg.

Peleg, who claims to have briefly worked for Visceral, has been working on EA’s most recent effort, ANTHEM, as a developer at Bioware, and has also worked for Naughty Dog. Most are familiar with how Electronic Arts has fared after DANTE’S INFERNO; keepin’ on keepin’ on with yearly sports game releases like Madden and FIFA, a couple of STAR WARS BATTLEFRONTs, TITANFALL, TITANFALL 2, and then APEX LEGENDS, always trying to see what the hot ticket is and always managing to stoke ire by either ruining it completely or attaching loads of microtransactions.

Writing this article took so long that in order to comply with Ethical Gaming Journalism I legally have to include this picture as a counterpoint.

Wieden+Kennedy were doing very well before DANTE’S INFERNO and have been doing very well afterwards, being the company that brought to life Old Spice’s “The Man Your Man Could Smell Like” campaign, as well as extensive work for Nike and being the source of Bud Light’s “Dilly Dilly” ad campaign. The company’s prowess would seem to shift the blame of DANTE’S performance onto the game itself. While the advertising for the game capitalized on the concept of “all press is good press,” and the hype was just enough to keep servers at Visceral humming, the “success” of the campaign truly depends on who is answering the question. Because again, while I have written several thousand words on DANTE’S INFERNO in the Year of Our Lord 2019, including its ad campaign, gameplay, and reception, I’m not sitting here writing an article about any of the game’s sequels.

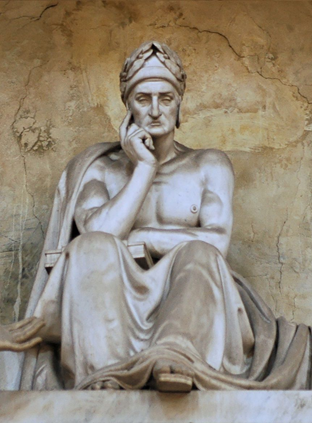

Dante Alighieri is still super dead and interred in the Basilica de San Francesco in Ravenna. Contemporary Florentines have done their best to walk back their condemnation of Dante, asking the city of Ravenna if they could please give them his remains, and even building a tomb for him in 1829 at the Basilica de Santa Croce if they should ever say yes. They have not, even though in 2008 Florence formally rescinded the threat of burning Dante at the stake if he ever returned, as was his sentence in 1302. He’s one of Italy’s most-celebrated minds, and his impact on Catholic culture and tradition has been immeasurable.

In this depiction of Dante from his empty tomb in Florence, we see the poet looking as jacked as the game depicts him, and also leaving the entire city on read

I think what mainly caused me to want to revisit DANTE’S INFERNO after 10 years was a desire to know “what happened,” for lack of a better term and to steal a bit from YouTuber Matt McMuscles, whose Let’s Play also was a contributing factor. It seemed that the team at Visceral had a better foundation and appreciation for the source material, and I think it was my own naivete that made me think that as long as they had an understanding of the source material and could properly incorporate it, they’d be fine. But what it seems to me is that the moment the DANTE’S INFERNO team was told that they had 18 months instead of three years, EA had basically blown their own kneecaps off.

Critics didn’t seem to mind too much that DANTE’S INFERNO played like GOD OF WAR—they minded that that was all there seemed to be to it. While it was no small feat to get the game out in that timeline, and the fact that it achieved commercial success notwithstanding, it seems to represent a sacrifice of not only thinking through the story elements, but also any other game mechanics that would’ve made the game stand out. And it would seem like EA’s hesitation to really nurse any creative venture also played a part as the fraying of the team dynamic and the presence of something newer, shinier, and more promising lead to the franchise’s shelving. What interested me most about the discontinuation was that despite the critical panning and in fact possibly thanks to the over-the-top marketing was that DANTE’S INFERNO did do well commercially. Despite how over-the-top, ridiculous, and even eye-rolling the marketing campaign was, Wieden + Kennedy, along with Jonathan Knight and EA’s marketing, helped sell enough copies to keep Visceral afloat and developing for another seven years. As this piece has come out it’s attracted fans that fondly remember the game and have taken umbrage at our ad copy referring to it as a “flop.”

DANTE’S INFERNO represents a sociological turning point in a way, and many of today’s gamers are holdovers from that era in video games and in culture. It came out in a time where there wasn’t nearly as much blowback for edginess for edginess’ sake, and it attempted to push the envelope into a direction where there wasn’t much more room left. Right on the cusp of the “are video games art” conversation, if it were released today DANTE’S INFERNO would fare much, much worse.The game’s sense of being aware of its own “epicness” and “brutality” feel dated at this point. Even the gameplay structure feels dated, as the dedication to recreating GOD OF WAR means that the game is trapped in the mid-2000s.

I’ve heard this sentiment echoed by a few developers and even filmmakers on Twitter, but the story of DANTE’S INFERNO really illustrates how much of a goddamned miracle it is that anything gets made, ever. So many factors need to align, and with such large, collectively-made products, there are so many chances for things to go askew. Maybe if the game had generated stronger critical buzz, maybe if development time hadn’t been cut to make it compete with GOD OF WAR 3, maybe if someone had convinced Knight not to give Lucifer a massive dong, I’d be writing about PARADSIO: THE GAME. We’ll never really know. And knowing why I won’t know honestly gives me a sense of peace.

**A previous version of this article cited Desilets and Knight as having met on THE SIMPSONS HIT & RUN. This has been corrected above, as the two met on 2007’s THE SIMPSONS GAME.

[…] INFERNO one of the 2010s’ strangest relics. Catch up on the beginnings of this Divine Comedy here if you haven’t […]