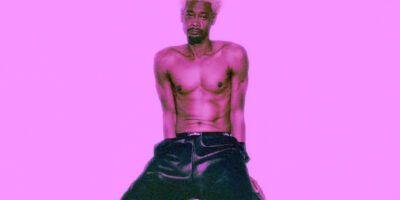

Mo Troper is one of the premiere power pop songwriters of our time. Since his tuneful, fuzzed-out solo debut BELOVED in 2016, the Portland-based musician has been steadily releasing LPs that have added muscle definition and ornate arrangements to his classic throwback hooks and witty-but-withering lyrics. For his latest release, Troper undertook a challenge worthy of lofty songwriters from Elliott Smith to Booker T and The MG’s and R. Stevie Moore alike: recording a full covers album of The Beatles’ REVOLVER, with all of the proceeds going towards Defense Fund PDX and Austin Mutual Aid.

Released in the summer of 1966, REVOLVER saw the Fab Four transition from the reigning pop mop-tops of the first half of their career to the countercultural trailblazers that would solidify them as arguably the most influential and certainly most documented and scrutinized rock band of all time. John Lennon’s comments earlier that year about the group becoming “more popular than Jesus” sparked an apoplectic response from the social and religious Right—the Ku Klux Klan picketed Beatles shows, records were ceremonially burned, and their songs were pulled from radio stations. They would never tour again. As such, the album has developed an enigmatic mystique, and many modern listeners consider it to be the ultimate Beatles LP.

We chatted with Mo and took a conversational, track-by-track walkthrough of REVOLVER, geeking out over Beatles facts and gaining insight into how he translated the Abbey Road studio masterpiece into a lo-fi bedroom pop companion.

The Beatles…The Alpha and Omega of power pop… something a friend once described as “the most insufferable thing white men love talking about.” As a gigantic Beatles fan myself, I’ve considered it recently, and I think I’ve always gravitated towards thinking of REVOLVER as their best record. What is it about REVOLVER that attracts you, or at least made you want to attempt to cover all of it?

Mo Troper: A couple things. Originally I wanted to do RUBBER SOUL, because I think REVOLVER is probably objectively their best album, but it’s not my favorite. It’s probably my second or third favorite. I guess I kind of realized doing RUBBER SOUL would be a little less challenging and more boring because the instrumentation on that record is more uniform.

It’s definitely in that folk-pop kind of lane still.

MT: Totally. And I ended up using no acoustic guitar on this cover album, even though there’s acoustic guitar on REVOLVER itself. I just didn’t feel like I could get away with it on RUBBER SOUL. I didn’t think I could get away with making those arrangements sound as convincing with the equipment I had and what I was using to record. So I ended up doing REVOLVER because there’s a lot of the keyboard stuff and a little more rockin’ stuff—it just seemed like it would be a little more fun and pleasant to listen to.

Not doing RUBBER SOUL means you wouldn’t have to play “Run for Your Life,” too.

MT: That is true! I guess the equivalent for REVOLVER is like “Yellow Submarine”—very different meaning, but a similarly obnoxious song that you wish you could skip entirely. It’s weird, like, REVOLVER is a really weird record. I think a lot of people don’t realize that the “REVOLVER as the best Beatles record” thing is revisionist. I don’t think people thought that until the UK tracklisting was widely available on CD, because it was a pretty unimpressive sequencing in the US. The thing about REVOLVER that is really cool, which was viewed as its weakness in the ’60s, was that it is a very transitional record and literally none of those songs were played live with the exception of “Paperback Writer.” So it was just in this blank spot in ’66. It seemed like there was some disinterest in The Beatles in ’66 still—I know they played these huge stadium tours, but reading Jon Savage’s 1966: The Year The Decade Exploded, he talks a little bit about how the The Beatles don’t seem to be the main story of that year. I think they might be, in retrospect, because they shaped the entire decade or whatever, but it seems that at the time “Paperback Writer” came out and was quickly brushed off the #1 spot by “Sunny Afternoon.” It’s a weird time for that band. I wonder what it would have been like to live through that album and if I would have been like, “Oh, they dried up.”

That’s funny. They really shot themselves in the foot that summer. Lennon said the “We’re more popular than Jesus” quote… I think in some respects—looking at it from the perspective of what it must have been like at the time—they had been on top for almost three years at that point. They had defined the conversation in pop music as the biggest boy band and were really defining their era, and I think people wanted to knock them down a peg.

MT: That’s the impression that I get, too. Which sucks—even those press conferences that were ostensibly about REVOLVER ended up being about the whole “bigger than Jesus” thing, but you actually can’t find a lot of dialogue about that album from the era, as far as I know. I know that Crawdaddy printed a pretty negative review. People really didn’t understand how much of an achievement that album was at the time.

The Ray Davies piece that I was looking into was really funny.

MT: Totally devastating!

It’s just so funny from the perspective of The Kinks starting to overtake The Beatles as a popular act—Ray has this huge chip on his shoulder. In some ways, he’s right, The Kinks introduced Eastern music and raga to pop music before The Beatles did, and Ray clocks that they were a little behind them. It’s fascinating to read that now knowing everything we know in hindsight. Tying it back to ’66 and now and the conversation between 2021 and 1966, there’s definitely a moment culturally right now that I feel is very in tune with that summer. You have civil rights riots happening throughout 1966 and 2020, the Klan is protesting Beatles concerts, stations are banning them left and right, and these people and institutions are trying to take down this signifier of the New Left, these pop stars trying to introduce a new cultural dialogue at the time. Relistening to all of those songs through, that lens has been really fascinating to me. I think that’s a perfect tie-in, too—having all of the proceeds of this album go towards mutual aid funds, there’s a very altruistic reason that you’re sharing this with everybody.

MT: I don’t think I could have, in good conscience, taken proceeds from a covers album—that seems very weird to me. And there was also no overheard, really. It’s not like I went to record drums in some nice-ass studio. It just felt like the thing that made the most sense.

How long have you had this project in the can?

MT: I recorded “And Your Bird Can Sing” last year and then basically just felt like I should do the whole thing. I wanted to stay limber. I wasn’t really doing anything. I had no reason to be playing music or recording music, so I wanted to have something to keep me busy.

It’s a cool quarantine album project, for sure.

MT: Thanks! I guess it does qualify as my “quarantine album.”

Taking everything track by track, starting off with “Taxman”… the best Libertarian rock song of all time?

MT: *laughs* Not a very relatable song, or a song that has aged particularly well. Musically, it’s a cool groove.

It’s a fun album opener.

MT: Sure. That is, like, bottom-tier Beatles for me.

Because of the content, “Taxman” is something I struggle with as a Beatles fan. Songs that ape that groove are usually better in my estimation than “Taxman” actually is. The most interesting thing to me about “Taxman” is, outside the fact that a 90% progressive tax sounds absolutely sick and there shouldn’t be anthemic songs denouncing that, that I do think sonically a big thread on REVOLVER is George Harrison coming into his own as a songwriter. The fact that they gave him the opening track on the album is insane!

MT: It’s crazy, yeah.

Lennon-McCartney were still holding him back a bit. He submitted “Isn’t It A Pity” for inclusion and they rejected it.

MT: That is so wild! I didn’t know about that until about a year ago. That is fucking nuts, I can’t even imagine that song being on REVOLVER.

One thing I like about “Taxman” is that solo McCartney does on it. McCartney always loved to kind of one-up everybody with a guitar solo every once in a while.

MT: I know—so showboaty!

That’s one thing I love about The Beatles, is that they all seem to want to best eachother.

MT: Sure, yeah. It is all four of them in the process of turning into what they became as individual solo musicians.

And it’s the first LP where they’re fully a studio band.

MT: I think it’s the first time where you hear Ringo playing those kinds of backwards fills. McCartney, obviously, comes to the forefront as a guitarist. There’s some John stuff that I think foreshadows the kind of lysergic nostalgia that he tapped into on “Strawberry Fields.” “When I was a boy / everything was right” is kind of a prelude to “Strawberry Fields.” It is very fascinating. RUBBER SOUL is a great album, obviously, but it’s harder to identify each member of the band on that album. On REVOLVER, you just sort of know who’s playing what guitar part, all that stuff is very identifiable.

The Beatles are just the ultimate “feel” band, and each member has such a specific feel, a signature style of playing that really comes out. REVOLVER being this peak Beatles album is in part because they’re still functioning as a four-person unit, as a rock band. Even if they’re incorporating all of these studio elements, at the end of the day these are basically still pop-rock songs, but there’s just something about the riffs… I think doing acid literally changed them. There’s this crazy, druggy, cool, acid-fried vibe to the record that really broadens out all of the playing and everyone’s contributions. I love that anecdote about Lennon and Harrison taking acid for the first time and cajoling McCartney and Starr to drop acid with them so that all four of them were on the same page—because Lennon and Harrison couldn’t relate to Paul and Ringo anymore since they hadn’t taken acid.

MT: When I lived in LA between 2016 and 2017, I went to a thing at the Grammy Museum where they played an original UK mono pressing of REVOLVER from start to finish. It was really cool. That is the other thing about REVOLVER—it hasn’t been as de-mystified in the same way that an album like SGT. PEPPER’S has been. Even the stuff on ANTHOLOGY— I’m pretty sure there’s alternate versions of “Got to Get You Into My Life,” “And Your Bird Can Sing,” and “I’m Only Sleeping,” and the arrangements are so radically different. How did they get from the weird version of “Got to Get You Into My Life” that was like only organ and drums to the fake Stax version that was on the album? Now that there’s been the Deluxe versions of SGT. PEPPER’S, WHITE ALBUM, and ABBEY ROAD, you can kind of see the development on their other masterpieces. It’s weird to me that there’s a real lack of that with REVOLVER. I think that’s another thing that makes it an appealing album to de-and-then-re-construct. I think with the harmonies, especially on REVOLVER, there is some truly weird shit going on. “Good Day Sunshine” has some of the most complicated harmonies that band has ever done. The “well well well you’re feeling fine” part of “Doctor Robert” has a very strange harmony that is George’s—if you isolate it, it sounds like a completely different melody. I think there’s less of those types of “mysteries” with other Beatles albums—either because the ones before REVOLVER are simpler, but also because the ones after have been so thoroughly deconstructed and dissected.

There’s an aura to REVOLVER, as corny as it sounds. Even more so than WHITE ALBUM—in a way, I feel like WHITE ALBUM was them trying to get back to the REVOLVER style of writing and recording as a band—the difference is that by WHITE ALBUM they all hated each other, and on REVOLVER they’re completely in sync. It’s kind of a mirror image of REVOLVER in terms of their own process in recording.

MT: Totally. I think that is super interesting.

Bringing it back to what you were saying about being able to pick out the sonic trademarks of the Beatles as solo musicians, and tying that to “Taxman”—a lot of the George Harrison signatures are all over that track melodically, even despite the fact that it’s so simple and it was fairly early in his own writing as a songwriter.

MT: And he was young as fuck! I think he was like 23?

Harrison is such a MVP on the album—so many of his parts are so tasteful. And he was the youngest member of the band, and to have to come out of the shadow of Lennon and McCartney had to have been super intimidating.

Speaking of a song with NO playing from George, or John, or Ringo (besides vocals): “Eleanor Rigby.” Probably one of the most evocative pop songs ever written. You did a really cool, keyboard-only version of the song. I mean, what else could you do, in the middle of a pandemic, and without George Martin and the huge recording budget The Beatles had. Your bedroom-pop “Eleanor Rigby” is great, and it made me realize how important the precise choices that McCartney makes singing, lyrically, all the way down—that song wouldn’t be as emotionally effective as it is without that very specific diction.

MT: Definitely! I would say that was probably the most challenging song to figure out how to do. I spent a really long time arranging it for MIDI strings, and I just could not go forward with that. It was the second song, and I feel like going from “Taxman” into this really castrated version of “Eleanor Rigby” would be a little too scary. So I ended up just doing a keyboard version. It was hard to settle for it, because the arrangement kind of is the song.

That’s one song where I really can’t divorce the song from the scene in YELLOW SUBMARINE.

MT: Me neither!

Seeing that scene as a kid and hearing that song along with it—I wasn’t scared, but it’s scary! It’s a scary song.

MT: It’s a really scary scene, too! It’s easily the darkest scene in that film, and sort of the weird, Upton Sinclair-style Industrial Revolution vibe is not something that you really encounter or know how to make sense of as a kid. There is something really depressing about that scene. That’s obviously my adult brain thinking about that scene, but when I was a kid I felt the same way. It’s inexplicably scary and depressing. It’s fucked up that it happens so early, too. It’s supposed to be Liverpool? And then Ringo is like kicking a stone around.

I didn’t know until I was researching this interview, but apparently George Martin was influenced by the PSYCHO score when he did the arrangement. You can totally hear that—that very staccato, sharp string sound. There’s a great story about them bringing in the chamber ensemble for the arrangement, and Geoff Emerick kept putting the mics very close to the stuffy, older musicians playing the strings to get a hotter sound.

MT: I guess that’s the other thing about that album that’s very transitional—recording engineers still wearing lab coats and shit. That’s the first album with Geoff Emerick. He was kind of a renegade, doing the close-mic drones and stuff.

And he was only 19 when he engineered REVOLVER.

MT: That is so fucked up. I’m trying to think of what I was doing when I was 19.

That’s what I love about a lot of that mid-period Beatles production—they’re trying out so much shit, and really throwing everything at the wall and seeing what sticks. I love the anecdotes of them describing production in very esoteric terms and forcing Geoff and George to figure it out.

MT: The classic is John on “Tomorrow Never Knows” saying that he wanted to sound like a Tibetan monk on a cliff, so they were just like, “Ah, cool! Let’s reverse the Leslie.” Like, being able to translate that is such a weird gift in itself.

It’s definitely this fun dichotomy between the drug-fueled, trippy band and the straight producer.

Next up is “I’m Only Sleeping”—y’know, a song about lying around sleeping all day. I think we’re both depressive boys, we get it. Very prototypical Lennon song, and it’s got that cool backwards guitar solo—how was recording that?

MT: It was cool! I ended up basically just doing another backwards guitar solo. I watched a YouTube video of someone playing the backwards guitar solo forwards, and just like… I feel very committed to making very reverent covers, but that was just a whole new level of shit I had to undertake. I really love the backwards solos on that song and I’m satisfied with how that arrangement turned out. I think it’s overall pretty reverent.

“Reverent” is a great word for the album in general—I think you really nailed a lot of the arrangements, a lot of the “feel”—even if you were more technically limited. It took Harrison several hours to record that guitar solo, so it wasn’t without effort! I love that you included the yawn, too. I love “Yawn, Paul.” On Beatles albums, you can always hear Lennon shouting out commands to them. You can hear the seams and the dynamics of the band a little bit, which is always a fun part of those old productions—that they include Easter eggs like that.

Going into “Love You To”—another very production-forward song, on top of being another prototypical George Harrison song. After introducing the sitar on “Norwegian Wood,” they’re fully going into this tabla/raga/“world music” thing. How did you end up replicating the drone and sitar on the original?

MT: It ended up just being all guitar on this arrangement. I’m pretty sure all the strings on the guitar were tuned to C or G. It’s basically just two notes. That was another one like “Eleanor Rigby” where I could have done a MIDI sitar or something, but I felt that would have been especially tasteless. I ended up just doing a “rock” sounding thing. That’s a delicate one—I think it’s a good song, I’m not crazy about any of the full sitar stuff that George did.

I think “Within You, Without You” is a little better.

MT: I agree. I think “Within You, Without You” is more viby. There is something a little jarring about the sequencing of REVOLVER. People don’t really talk about how the first four songs on REVOLVER are all in minor keys, which is like… I can’t think of any other Beatles album that that’s the case for. When people talk about REVOLVER being a “darker” album, I think that’s something that contributes to that vibe.

There’s a weird tritone vibe to REVOLVER… Hail Satan, y’know.

MT: Sure. “Eleanor Rigby”’s vocal melody is in the same mode as “Scarborough Fair,” so it’s got this not quite major or minor, modal tone. And then, obviously, with the Indian-inspired solo in “Taxman,” I think you’re right—on the first side of REVOLVER that’s pretty pervasive.

MT: And then things suddenly get way sweeter with “Here, There, and Everywhere” which is so triumphantly major key.

That’s a great transition into “Here, There, and Everywhere”—that song is really an early example of—when I alluded to The Beatles having a conversation with their contemporaries in their own songwriting, that’s a huge example. The legend of that song is that Lennon-McCartney wrote that after attending a listening party for PET SOUNDS. The intro to that song has the very PET SOUNDS-y kind of vocal harmonies. This romantic, nostalgic, wistful, “Waterloo Sunset” kind of vibe to that was shared with The Beach Boys and The Lovin’ Spoonful singles at the time. Considering Brian was chiefly influenced by RUBBER SOUL when he wrote PET SOUNDS, for them to in turn write a song that was inspired by PET SOUNDS is this nice full-circle moment.

MT: I love that story about them being so inspired by the preview of PET SOUNDS that they wrote a song for REVOLVER—that’s such a great story. It’s such a beautiful song. It’s crazy that “Here, There, and Everywhere” and “For No One” are on the same album and by the same person, and about the same person. It’s such a rare McCartney song that is completely unadorned. It lacks that master of ceremonies vibe that I feel like he’s so well known for even with his ballads.

The pomp and circumstance.

MT: Yeah! Like, even on the early ballads like “Yesterday” it’s hard to know whether he actually means it. I think with stuff like “Honey Pie,” it’s like he clearly doesn’t mean it, he’s not writing from an emotional place at all anymore. The love songs on REVOLVER are so interesting for that reason. I know that Elliott Smith used to cover “For No One”—it’s like Emo McCartney, in a way he never was before or after REVOLVER.

In a way, Lennon started dominating that side of the band, lyrically at least, and even conceptually. Lennon got way more barbaric, for lack of a better word—very in tune with his emotions. McCartney was doing a lot more pastiche. When McCartney can get cutesy, he can get really cutesy! That treacly vibe—even though obviously he’s a master. Even in McCartney’s goofiest songs, there’s a level of craft going on that makes it where I can’t even completely hate it no matter how annoying he’s attempting to be.

MT: Everything I say that sounds disparaging about The Beatles is not actually disparaging—to hate The Beatles is to love The Beatles.

For sure—being as into them and as deeply into them as I have been for over half my life, you realize that they were assholes. I think every member of The Beatles is a different stripe of asshole in their own way, but they’re fascinating individuals. I think that’s why people have rankings of which one is the best. That’s why their whole mythos and everything about them has translated and lasted so long. You can really deep dive into it, and it’s rewarding, and they’re so well documented. One thing I remember about getting into The Beatles in high school is how each one of the Wikipedia pages for their songs was like exhaustively toiled over. You could learn so much just through browsing Wikipedia. They’re probably the most extensively written about and researched rock band of the era.

Anyway, “Here, There, and Everywhere” is Art Garfunkel’s favorite pop song, and I just think that’s nice.

MT: That is really nice!

And speaking of Very Nice, we have “Yellow Submarine”! Tyler from Diners contributes vocals to your version, which is super fun. “Yellow Submarine” is a bit of a novelty, children’s folk-pop Donovan song. Maybe a precursor to “The Mollusk” by Ween. It’s insane to me that “Yellow Submarine” was the double A-side they released that summer with “Eleanor Rigby”—and that was the first time they released album cuts as a double A-side single on the radio.

MT: God, that’s crazy. A couple things about “Yellow Submarine”—I never understood the underwater thing. I think it’s some kind of thing in the UK, this maybe sort of Edwardian fascination with BIOSHOCK-type aesthetics that was present in comic books and science fiction for people in The Beatles’ parents’ generation.

If Tales of the Black Freighter from WATCHMEN is anything to go off of, there must have been some kind of nautical pulp fiction thing in Britain.

MT: I don’t know too much about it, but that’s the one thing about that song. People think it’s kind of nonsensical, or there’s no real context for it. People always go, “they must have been really smoking something, because they wrote a song about a submarine”—but it seems like there’s some kind of missing context for it. It’s still a pretty stupid song. *laughs*

They loved throwing all this weird shit at Ringo, and they loved doing nautical Ringo songs.

MT: Yeah, very weird. Tyler was in that band Okilly Dokilly—the Ned Flanders themed metalcore band—and they would cover “Yellow Submarine” live, so that’s the connection. I originally wanted Tyler to do “Good Day Sunshine” because I thought they would do a great job and it was sort of a more “real” song, but then they sort of insisted on doing “Yellow Submarine.”

Tyler just did our Dime in the JQBX event—so the synergy here at Merry-Go-Round Magazine is really on the ball.

MT: I love that, and I love Tyler! Diners toured with us like two years ago and it was awesome.

It’s crazy to think that the summer The Beatles are inciting Klan riots and having their songs pulled from the radio, the song they were pulling from the radio was “Yellow Submarine.” *laughs*

MT: *laughs* That is really funny! Jesus.

Things were just as weird then as they are now, I guess. That’s the story of humanity.

“She Said She Said” is one of the best rock songs on REVOLVER, a riff that absolutely rips—cool lyrics about tripping on acid with Peter Fonda and him getting all Mephisto on your ass. I really love your version—has some great Velvet Crush kind of vibes, and it gets into that power pop “zone.” Another great Harrison tone on REVOLVER. Has that Beatles/Byrds sound exchange going on—probably intentionally Byrds-y considering the acid trip that inspired the song was with The Byrds. Crosby was showing them how to do Eastern scales on guitar, so I think Crosby has an influence on a lot of the weird riffs and tonal shifts on the album overall.

MT: The thing about the leads on REVOLVER, and “She Said, She Said” in particular is that they’re not especially intuitive to play. There were some riffs where I wasn’t really sure what position George was playing them in, or if the guitars were even in the standard turning. It feels like the Donovan fingerpicking on WHITE ALBUM, where there’s a consistent external influence—so that makes sense. It seems like they were clearly trying to go for this Eastern thing throughout that album, and there’s weird blue notes and chromatic notes from the guitar and the bass that you wouldn’t really learn unless you were actually studying The Beatles.

They’re marrying these new things and techniques they’re learning with that classic HARD DAY’S NIGHT chimey sound that initially influenced The Byrds—they invented the Rickenbacker chime, and then completely reshape it and shift it, transforming it and evolving it. And it’s just a great rock song.

We’ve got that vaudevillian McCartney on “Good Day Sunshine”—sunny/funny McCartney, a very evergreen McCartney writing mode. A lot of McCartney tracks on REVOLVER have that fun sunshine-pop vibe to them—maybe some Lovin’ Spoonful or Kinks trace there. Lots of key changes and meter trickery, too.

MT: A very challenging song on keyboard. Like I said, some of the most challenging vocal harmonies—at the end, it modulates the key changes a half-step so it goes from E Major to F Major at the very end, so all the harmonies shift up a half-step, which is really disorienting. In some ways it foreshadows “Penny Lane,” which changes keys like eight times. In some ways, I wish I could’ve heard it when it came out, because I wonder if it would have had a jarring effect… now, it’s just so canonized. People don’t think about it as an unusual piece of music, when it is. It has a lot of merit musically. It was a very cool song to deconstruct.

The Beatles have always had kind of a perfect “Sunday morning music” vibe on a lot of their tracks, and there’s really nothing better in that lane of pop music than “Good Day Sunshine.”

Sequencing-wise, in the middle of REVOLVER they start doing really “up” rock songs and really fun pop songs. “And Your Bird Can Sing” has another monster riff, kind of inventing Thin Lizzy with the dual guitar harmonies. Another super fun song and fun Lennon rock song.

MT: I think that song is also quintessential proto-power pop. “And Your Bird Can Sing” and “Ticket to Ride” are really the two things I would point to as being the blueprint for a band like The Raspberries or something.

Driving, riffy pop-rock music that has a very contemporaneous sunshine-pop kind of vibe to it.

MT: I love that song, I think it’s great. I think it’s the start of Lennon’s weird obscure diss track mode—“Baby You’re A Rich Man” feels like a similar conceit. Also, like, “Glass Onion,” or, like, “The Ballad of John and Yoko”… he just seemed to develop this way of talking shit suddenly. I’m pretty sure it’s also the last time he used his Rickenbacker 325 on record. I think that he completely switched to the Epiphone Casino after “And Your Bird Can Sing.” That’s like a cool gear thing I guess.

I am a gigantic nerd for that. When I went to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame a decade ago, they had both Lennon and Harrison’s Ricks from BEATLES FOR SALE on display and I was freaking out. It’s funny, because “She Said, She Said” also has that Lennon diss track vibe to it. There’s that Lennon mode of songwriting where he’s just being a backhanded asshole. It’s very noticeable that he’s starting to develop that lane on REVOLVER. One thing about those kinds of Lennon songs was that—when he was a little more assured as a songwriter and overtly in control of his production, his songs tend to get in the weeds a bit. “And Your Bird Can Sing” and “She Said, She Said” both have rock solid arrangements due to the band being so in sync. When he was still relying on the Lennon-McCartney songwriting partnership and bouncing ideas off the band, everything they did got elevated because they were all bringing out the best in each other.

MT: I think that John was probably the worst arranger in the band. I get the sense that a lot of his songs were sort of skeletons that were then fleshed out by either George Martin or Paul McCartney, usually. I know that Paul McCartney didn’t play on “She Said, She Said” and I get the feeling that Ringo had a pretty heavy involvement in the arrangement there because of how fundamental and essential those drums are to the arrangement of the song. And then, “And Your Bird Can Sing” is very clearly a McCartney arrangement, I think. I know some people think McCartney played both of the harmonized guitar parts. There’s a lot of interplay between the guitar lead and the bass line, so that would make a lot of sense.

It’s almost a Rundgren kind of vibe, that makes sense.

MT: Yeah, totally. Definitely. I feel like Rundgren’s “Couldn’t I Just Tell You” does a lot of guitaromnies before they were in vogue.

Just that style of late ‘60s/early ‘70s vibe of proto-bedroom pop that McCartney was doing and Rundgren was doing and Stevie Wonder and Emitt Rhodes. Even though that’s a Lennon song—it’s still prototypical of that style.

Going into “For No One,” you mentioned it before, but a truly classic McCartney baroque-pop ballad. I really liked how you transposed the French horn solo to keys. Kind of a proggy vibe that I liked. Talk about that a bit.

MT: I mean, what can you say? A great song, one of the most beautiful songs. I was talking to my friend Nathan from Cool Original recently, and he was telling me about this Tweet that said “‘You’ is the cowards’ ‘I’ in songwriting.” I thought that was kind of weird, because this is a pretty obvious example of an autobiographical song that’s written in the second person. Like if he was singing “I wake up…” it would be pretty corny. *laughs* It’s a great example of a song written in the second person that’s impossible to imagine being written in the first person, and it makes a lot of sense that Elliott Smith covered this song, because Elliott Smith was also a master of that device. It’s so hard to discern what songs are Elliott Smith’s or which is like a character song. I think this song is pretty revolutionary in that respect—a crazy literate lyric from McCartney, who doesn’t really get enough credit as a great lyricist, because sometimes he’s terrible. I think this is some of his best lyrics.

McCartney can either toss something off because he’s having fun, or he can actually try. He has like “try mode” and “fun mode.”

MT: Party mode.

For sure! It’s interesting that you bring up how it’s in the second person and so literate, though. In a way, it’s a precursor to “She’s Leaving Home,” a similar character portrait and kind of evocative lyrically in the same way as “For No One.”

MT: One other thing that’s interesting about “For No One” is that it’s literally the exact same chord progression as the chorus to “Hello Goodbye”—literally the same chords.

Another song that we mentioned a little earlier. “Doctor Robert” is an evergreen Lennon song, kind of a prototypical The Band “medicine man as dealer” vibe. Some more tasteful lead guitar from George.

MT: It’s definitely a weird deep cut—I think this section of REVOLVER in general is weird deep cut territory. There’s a lyric in “Doctor Robert” I had never known: “My friend works for the national health / he pays money just to see himself.” I’m not sure if that’s the lyric, and I tried to corroborate, but Genius and all these sites had different lyrics for that part of the song. Some had “he’ll pay money,” some had “she’ll pay money just to see herself”—that’s one sort of mystery. I’m not sure if there’s a lyric insert that came with the album or not and had misprinted lyrics, or what the actual lyrics are. It made me feel nuts, like, “How the fuck can I not figure this out… this isn’t a DIY band…”

Could have been a Northern Songs thing. That reminds me—I was looking up all of the old sheet music covers they did for every track on REVOLVER—they all have these cute, cartoony, Age of Aquarius kind of images of the sun—I just really like that vibe and wanted to bring it up.

Another incredible early George track. I definitely think Lennon and McCartney were a little intimidated by George Harrison, and how he was developing as a preternaturally talented songwriter. Despite that, Lennon and McCartney both elevated George’s songs—McCartney’s piano on “I Want to Tell You” adds so much to the track, and coupled with George’s guitar parts it makes for a really fun track—really cool, noodly guitar riffs and licks all over the track.

MT: I think that that song is a very underrated song on REVOLVER and in The Beatles catalogue in general. Speaking of Elliott Smith, I think it’s totally the aesthetic of FIGURE 8 embodied in this song. A lot of the chord changes are very reminiscent of solo George stuff—really complex, guitar-head chord changes.

It’s really discordant, and the piano is discordant. It sounds pretty gloomy despite being in a major key.

MT: It’s like a half-diminished chord I think. And yeah, the piano on top of it just adds a very weird character. McCartney’s harmony is insane, it’s so high.

I’m a huge sucker for deep-cut George Harrison tracks, “Blue Jay Way,” “Only A Northern Song.”

MT: Me too! “It’s All Too Much.” George stuff is crazy.

They all have this really cool, kind of prototypical Sonic Youth drone thing going on, which I think you tapped into on your “Love You To” cover, and which SY tapped into on their “Within You, Without You” cover. Kind of a proto-shoegaze vibe.

MT: It is very Creation Records-era Beatles.

Between Primal Scream, Oasis, Brian Jonestown Massacre—Britpop in general owed a huge debt to them experimenting as a rock band like that.

Honestly, “Got To Get You Into My Life” is my favorite song on the record, personally. As a Michigander, I love that it’s got the Motown/Stax horns. The Motown sound is a big influence on the record, between that song and “Taxman” to an extent. Probably the best song about smoking weed ever. I love that you have synth horns on your version, that’s really fun!

MT: The weird biographical detail of that song is that The Beatles wanted to record all of REVOLVER at Stax initially, and there was some kind of conflict where EMI wouldn’t let them record the record in America, which is insane to think about… that they wouldn’t grant THE BEATLES that liberty. I definitely feel that “Got To Get You Into My Life”—despite the weird SMILEY SMILE-esque version on ANTHOLOGY—I’m not sure how it evolved to that point. I love the guitar break at the end and how it transforms into a completely different song. There’s weird guitars with tremolo along with the horns that’s kind of disporate and doesn’t make sense, but is very cool. It kind of goes from being a Motown/Stax pastiche to a record that never could or would have been made at Motown or Stax. It turns into and reveals itself as a Beatles record.

It’s transformative. It’s funny because Ray Davies mentions how the British jazz session players they got couldn’t swing like American horn sections. You can kinda hear that! It’s funny to transpose that horn arrangement to the keyboard, because it kind of works in that way.

MT: ‘Cuz it’s kind of stiff!

Exactly, and the way the rest of the song is produced makes it not seem like they’re just appropriating Motown/Stax as a result but instead McCartney is taking in the influence and making a McCartney version of it.

MT: That’s also one of my favorite songs on the record. I sometimes feel like that’s an unusual opinion, so you’re not alone in feeling that way.

I always love the “statement” Beatles closing tracks—“Twist and Shout,” “A Hard Day’s Night,” “A Day in The Life,” “The End…” I think “Tomorrow Never Knows” is certainly worthy of that pantheon.

MT: “Run for Your Life”?

Oh yes, obviously “Run For Your Life”! “Run For Your Life” toppled over all of those. But seriously… another song that probably invented shoegaze. Love the needle drop in the finale of MAD MEN S5. What can you really say about “Tomorrow Never Knows”? One of the biggest statements on an album that was already as expansive and reaching as REVOLVER is. They were tapped into something that people are tapping into even now. It’s a cliche, but it sounds just as crazy and forward-thinking now as it did then. All of The Beatles avant-garde experiments have this quality to them that is still so palpable—they make everything sound so fun to listen to.

MT: Definitely. This is probably the song I had the most fun recording. I didn’t feel like I had to honor any kind of arrangement.

How did you tackle all of those tape loops?

MT: It’s just all guitar. I just tried to play those parts on guitar.

So you basically just made LOVELESS then!

MT: Ha yeah, there were a lot of guitar tracks! I tried to do this thing where I slowed the master down, and it wound up where the whole master sounded like it was going through a Leslie, so I was like “Okay, I’ll just keep that!” It was really cool. I was recording vocals and my dogs were barking in the background, so I kept that in. The guitar solo was fun to play. It’s probably the only song from this project I would consider doing live with the band. The arrangement is a fun rock song.

There’s a fun vibe to the whole song—I feel like the bassline is very purposefully reminiscent of “Taxman”—kind of doing this weird call-and-response to each other as the opening and ending tracks on the album. One thing we haven’t brought up as much is the absolute unit that is Ringo Starr on REVOLVER. Great Ringo track. Ringo is putting in a lot of work on REVOLVER as a whole.

MT: I feel like that drum pattern that Ringo plays on “Tomorrow Never Knows” has become one of the most imitated beats—that syncopated beat he kind of played in “Ticket to Ride” too. The way he played, where he was left-handed but played a right-handed kit—that’s why he played a lot of reverse fills. It seems like he really embraced that on REVOLVER. Before that, he was fighting to be a conventional rock drummer, but on REVOLVER he just decided “I’m going to play in this fucked up way that’s intuitive to me.” He created this thing that’s totally inimitable.

The signature Ringo feel is all over REVOLVER.

MT: I think that’s the first time Geoff Emerick close-miced the drums. There is probably more incentive for Ringo to play all of the drums when there’s not just a single overhead mic.

Really exploring the kit.

MT: Exactly. Great drummer. I hate when people talk shit on Ringo. It’s just become this weird, trite thing; the anti-Ringo sentiment. It feels like someone is talking shit on your uncle or something.

He was the oldest member of the band.

MT: The avuncular figure.

I think even within the inter-band dynamics there was that sentiment. There’s the famous Lennon quote where he says “Ringo wasn’t even the best drummer in The Beatles,” which is a classic mean, bitchy Lennon thing to say. Ringo really is one of those drummers where you can isolate his drum tracks and still be able to tell exactly what song you’re hearing.

That kind of helps to bridge the final thing I wanted to discuss—you included “Paperback Writer” and “Rain” as bonus tracks—two really great songs, two of my favorite Beatles singles. You’ve brought up “Ticket to Ride” as a stylistic reference—I think “Paperback Writer” and “Rain” both tap into that chime-y, proto-power pop energy you had mentioned. On top of that—threading what we had talked about—both songs also feature drone elements, taking that to the next level. Very riff-y, droney, proto-indie rock songs. What was it like tackling those?

MT: “Paperback Writer” also has some of the most challenging harmonies ever. That intro is really challenging—that was hard to reconstruct. “Rain” is probably my favorite song from the REVOLVER sessions. I feel like I put a lot of heart into that cover, which is why I decided to “premiere” it before the rest of the album. I was committed to using the same key as the song, and it’s in between G flat and G major, so I had to find the exact point the guitars were tuned at. Just a phenomenal guitar part. What a great song. As someone who grew up in Portland, too, it’s just a very relevant vibe. I thought that as a kid, too. There are definitely a lot of people—especially people who aren’t from here—who bitch about the rain.

You can grab a copy of Mo Troper’s REVOLVER over on Bandcamp. All proceeds go to Defense Fund PDX

Comments