When most people decide to play a video game, it’s probably a safe bet we’re not contemplating any big “why” to that decision. After all, it’s just entertainment, right? Well, the truth tends to be a bit more complicated than that. Most games we play, whether for sociability or time-killing, primarily serve as a means of escapism; it’s a way for us to temporarily evict ourselves from the stresses of life through pleasant distraction and stimuli, all with the goal of returning us to reality with less negative thoughts than what we started with. Yet when you opt to view the medium through that lens, a few different, more complex questions start to arise: if the point of play is escapism, why do people willingly invest in games that revolve around personal tragedy, or otherwise trigger feelings that hit close to home? Or, perhaps more pressing, at what point does escapism stop being a temporary relief from reality, and more of a replacement for it?

As someone who spends excessive amounts of time with the former, at least one part of the equation becomes clear: they bring a cathartic, almost morbid comfort. There’s a certain solace to be found in exploring these kinds of personal expression, highlighting ugly bits of the human condition largely because, at some point, we all will be faced with them, be it death, trauma, or mental illness. And while indulging in this niche runs seemingly antithetical to the escapism many expect of games, the bittersweet takeaway of seeing experiences such as these through to the end, no matter how uncomfortable the events that precede it, more often than not acts as a net positive by helping us cope with and vicariously process reality in addition to making the time we’ve spent memorable. As for how to address the latter question, one need only look to a recent little hidden gem, OMORI, to find an artistically poignant answer.

Welcome to White Space

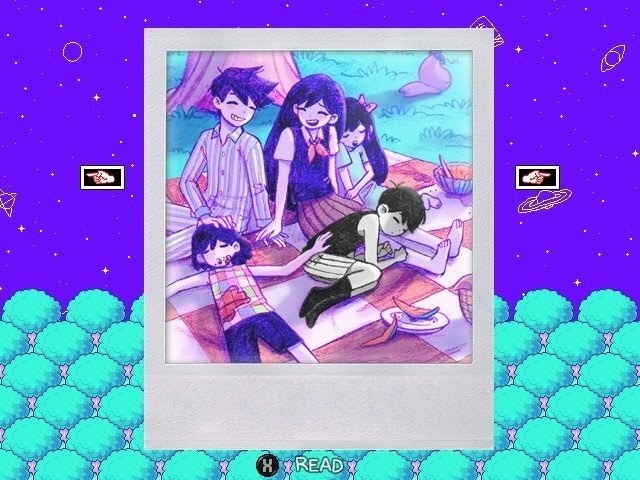

It all begins with a consoling message: “Everything is going to be okay”. We wake up to White Space, a place we’ve lived for as long as we can remember. Cold, vast and empty, it is devoid of all but some bare essentials, a black light bulb, and a door. As we pass through this door, we’re met with a colorful dreamscape with our friends waiting for us, ready for a day of games, picnics, and sifting through fond memories in a photo album. The feelings here are warm, idyllic: in a word, “happy”. Though as we recover photos from the ground after a friendly little spat and put them in their proper place, one seems to fall from the album. It’s Something we weren’t supposed to see. We’re returned to White Space, alone once again… Our eyes open, a boy alone in a dark house, everything packed away in boxes; three days left until we move away.

OMORI is a relic of a time long since past: a humble gift born of 2010s tumblr comics and given form in RPGmaker, taking clear inspiration from the likes of EARTHBOUND and YUME NIKKI in order to share its story. And like plenty of its ilk with similar roots, whether it be UNDERTALE, OFF, or LISA: THE PAINFUL, it’s a piece whose surreal and even charming exterior belies a deep psychological dread, one that upsets viscerally in moments of weakness while clinging to your psyche in others, even in long stretches where we retreat back into cozy facade. For all intents and purposes, it’s a game most people, especially in times we face now, probably would be reluctant to contend with. But if you can tolerate its portrayals of grief, depression, and the ordeals of moving on, the overall message that strings this 30-hour journey together is well worth any existential baggage and ugly tears saddled along with it.

One of these things is not like the other

The throughline is effectively split navigating two parts. On one end, there’s Headspace, where we spend the majority of our playtime by partaking in the wacky hijinks you expect from a retro RPG: getting into battles with punny creatures, completing a ton of random side quests, and generally just having a good ol’ time with our friends. On the other end is the Real World, a place to spend our brief visits of lucidity reminiscing, tying up loose ends, and slowly piecing together what led our main character to shutting himself away from the world. And while neither of these premises come off feeling particularly “new” for the indie scene to tackle, the way these familiar ideas seamlessly complement each other and portray the two halves of our character’s mental life makes the game feel authentically intimate.

It’s obvious even early on that Headspace is just one big coping mechanism for whatever plagues the protagonist outside of it. And as such, OMORI is very deliberate in this world’s escapist filter, projecting plenty of fun and cozy vibes throughout the adventure in order to obscure any of the faults that lie further within. The main thrust of our quest within this cerebral comfort blanket, trying to find a lost friend, is simple enough in the beginning. But with repeated trips to Headspace, the task convolutes to the point that it becomes little more than an excuse to take our pajamaed pals to all sorts of fun locales and creative diversions, whether it be deserts full of dopey dinos and dunes of brown sugar, a pastel-pink garbage planet to fight off sentient dial-up, or venturing far and wide in search of special hangout spots and corny dad jokes.

This motif of childlike escape is perhaps best exemplified in the art direction. Between all the character portraits, cutaways and animations that project a lovingly sketched color-pencil aesthetic, to the massive soundtrack that runs the gamut from “whimsically innocent” to “intensely dramatic”, to little quirks like turning our party members into .JPEGs of toast upon being KO’ed, the handcrafted quality of the elements sprinkled into the already endearing atmosphere supplement its appeal, injecting a kind of wholesome meta-nostalgia to it all. It not only gives extra personality to the limited engine running the whole show, but more importantly suckers the player into sticking around in the dreamscape for as long as possible. Which, considering Headspace’s role within the narrative, is a bit insidious in its own right.

Reject Modernity. Embrace Funni Bonk

However, it is the segments while awake that coax out the game’s more tragic aspects. It’s how the player gets to experience the “real” side of OMORI: the heavier emotions that make characters feel tangible, the underlying truth behind a fractured group of friends, and the personified horror that follows alongside trauma, both metaphorically and literally. We start to emulate all the same fear and genuine unease eating away at us even in what should be benign activity within a quiet little suburb, the ways it limits our ability to perform something as simple as taking care of ourselves or reaching out to others. Sure, there are plenty of good, even legitimately heartwarming moments tucked away in the departures from Headspace, but as we get further into the mystery and slowly parse the subtext, the more things seem to spiral in both worlds as a consequence. It’s a feeling anyone that suffers from depression or anxiety will find uncomfortably familiar, that when faced with personal demons or debilitative thinking, oftentimes it’s easier to repress rather than face reality. And it is this that lays at the heart of what makes OMORI as poignant as it is.

Any group of people, friends of otherwise, will have completely different ways of dealing with the same loss and change. The desire to isolate away from the emotional and consequential strain of either is a common temptation, especially among those with depressive tendencies. And to a certain extent, you could argue it’s a necessary part of both life and the recovery process to indulge in a bit of escapism. But the pleasure of escape is ultimately a double-edged sword: the longer you spend immersed in comfortably-numb fantasy, regardless of the reason, the harder it will ultimately be to accept harsh truths and go back out to face them. At worst, you may even regress, and simply let the attachment to that fantasy consume you until there is nothing left.

There’s Something behind you.

As is the case in life, the way the characters in OMORI’s story resolve their anguish is ultimately a personal choice. OMORI shows the kind of dark, self-destructive places the mind can go even if presented in a lovingly peachy light, and how grief and guilt can metastasize into something much more haunting. But at the same time, it shares one other crucial insight: there will always be an opportunity to overcome the things that haunt you. It may be scary, or painful, and take you out of that protective bubble, but the possibility to move on toward a better life will always be there. You just have to be willing to take the first step.

Comments