In 2009 Steven Porfiri was accused of never having played a video game before by someone on a GameFAQs message board, and the insult has haunted him ever since. Now, as the Senior Games Writer for Merry-Go-Round Magazine, he’s finally been given a platform to prove that not only has he been playing video games, he writes about them as well. I Played a Game Once is an inside look into what he is playing, and how it has any bearing whatsoever on our current moment. It’s basically like Carrie Bradshaw’s column but with more discussions about save-scumming.

The world, I have noticed, is not getting any less bleak.

As such, I wanted to finally play HOLLOW KNIGHT because I felt like a small bug wielding a nail in a dark, unforgiving world mired with terrors that I don’t quite understand.

I have to say I certainly got what I came for.

In the interest of total transparency I have not completed HOLLOW KNIGHT, mostly because I didn’t quite anticipate how long this game is, and how much time needs to be put into it if you’re not relying on a walkthrough.

Ah jeez ah Christ that’s so much game to play

But put time into it I did! And you know how everyone praises it as a melancholic, deeply atmospheric adventure through a mysterious world with a dark past? They’re right! Reviewers have compared the game to DARK SOULS before, possibly due to its similar difficulties, but I found it was very similar to another atmospheric metroidvania I’d played before: BLASPHEMOUS. Like HOLLOW KNIGHT, BLASPHEMOUS also features a lone, silent character on a journey through an unforgiving land ravaged by a mysterious force. This character has a mission, and though the player doesn’t quite understand what it is or why their character undertakes it, they know that they have to for whatever reason.

“Gotta fill my hat with blood and pour it on my head for the LORD.”

These sorts of scenarios work very well in the modern metroidvania, as they’re all about exploration and discovery as well as backtracking and decision-making. These worlds are as unfamiliar as to the character as they are to the player, but the single-mindedness of the story mission and the player mission match up somewhat, even if the story doesn’t give the player much info on why they’re doing what they’re doing. In HOLLOW KNIGHT the mission is, so far, to kill the Dreamers and awaken whatever’s in the Black Egg. Or at least that’s what it seems. The player doesn’t know what this does, exactly, or what this will do, but if most of them are like me they assume that doing this will reverse the mysterious affliction that is causing the bugs of the world to attack me, and possibly bring back a sort of prosperity to the broken world of Hallow Nest.

Likewise, in BLASPHEMOUS the mission seems to be to slay the monstrous creations of The Miracle, and maybe restore a sense of order to the world if you’ve got an extra second or two. The Penitent One doesn’t really seem to have much of a backstory or a clear direction at times, other than the various quests given to him by the inhabitants of Custodia, but there is a definite area that the PO needs to get to in order to complete the game, an implied destination.

Hopefully therapy to discuss those years of Catholic upbringing

But even though the player doesn’t really know what’s driving the character, they’re still propelled forward. The player is naturally driven through the game by virtue of playing the game, by wanting to explore this world they’ve opened. These games rely on the player’s curiosity to be driven forward, and can get away with a cryptic story and cryptic character. When you play pretty much any game you want to know what your character’s motivation is, so when these games just kind of open into exploration mode and you’ve been given a brief and abbreviated rundown on the world around you, you do just kind of want to know more. The positive feedback loop of exploring the world and adding to your map just kind of adds to this need to explore. In BLASPHEMOUS the map just sort of fills in as you go along, so each new screen has the potential for a new area entirely, along with new dangers and new items. HOLLOW KNIGHT has an interesting and arguably more challenging method, requiring the player to purchase an item that updates the map and then either purchasing or running into the mapmaker to get the base map for a particular area. The new locations the player finds while exploring can’t be added to the map until they sit down at one of the numerous benches throughout the world, which also act as a mechanic similar to the bonfires of the Dark Souls series.

Love a game where the point is to have a nice sit with a friend

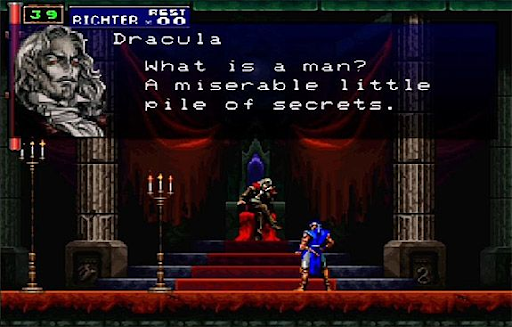

As most of us are aware at this point, the term “Metroidvania” is a portmanteau of two classic video games from which a larger genre is generally seen to derive their mechanics: Castlevania and Metroid. If you look at the first couple of Castlevanias in particular, it’s interesting to note how the call to action sort of develops as game design progresses. In the first game the intro is largely “This vampire is in a castle and you HATE that.” There’s not a lot of explanation in-game, and if you want more info you’d better hope the user’s manual is well-written. But by CASTLEVANIA II there’s a little more explanation and more story to bring the player in, and you eventually get to “What a horrible night to have a curse.” From then onward the games are given the usual sort of Castlevania setup, which is, essentially “This vampire is in a castle and you hate that,” but slightly more detailed.

Dracula won’t stop drinking and discussing philosophy! Are you a bad enough dude to break in there and make him share his Franzia???

Once games like HOLLOW KNIGHT begin merging the concepts of the Castlevania series with Metroid, you begin to see games that can more rely on a vague story using the player’s innate curiosity to initiate gameplay. There are tons of other games outside these two narrow examples, of course, and game design, like every form of creation, stands on the shoulders of those that came before it. It’s nonetheless interesting to see how the melding of these two concepts in this way helped to develop new ways of looking at storytelling and imagining game mechanics.

As I’ve been inexorably pulled through HOLLOW KNIGHT, and as I’ve seen the world it has to offer, I keep reflecting on that. HOLLOW KNIGHT tugs on me because I’m genuinely interested in seeing what else is there and where the story will eventually bring me. I want to explore because I want to see how everything falls into place and what my hand in shaping that story truly is. I worry that it’s not a great effect I have on the world, as I’m starting to see what I assume are the consequences of my actions wreaking havoc on Hallownest. But I’m still going to move forward. And up. And down. And slash at dead-ends in case they’re hidden pathways. Because sometimes when the world is dark and bleak and you feel like a very small bug with a very small sword, it’s all you can do.

Comments