Breakup albums are one of the easiest ways one can enter music’s canon. Whether it’s the greater pop music canon, or the canon of your average 19 year old with a late night college radio show, songs about heartbreak and love lost are universal. And throughout most breakup albums, there is usually an inherent toxicity in the air, whether it’s emanating from the performer or its subject.

In the early 2010s, this toxicity was taking on new shapes in the world of hip-hop/R&B. Artists were becoming more self-aware of that toxicity, and using that self-awareness to fuel some admittedly great music—or, at the very least, music that was clearly landing with fans throughout the world. The clearest example of this was The Weeknd, as his initial mixtape trilogy (HOUSE OF BALLOONS, THURSDAY, and ECHOES OF SILENCE) quickly became influential and set the template for many within the larger pop sphere. While these mixtapes weren’t inherently breakup albums, it was clear that a sense of heartbreak lingered over them; it’s a similar story with Drake, as “Marvins Room” shook the hip-hop world by storm with its naked honesty and dreamy atmosphere, clearly inspired by The Weeknd, who’d go on to contribute to TAKE CARE later in the year, an album that solidified him as the biggest name in not only hip-hop, but pop music at large a few years down the line.

The Weeknd was one of the last acts to really break through during the blog era, at least on a major scale. But he wasn’t the only name making headlines on these music blogs in 2011, as UK electronic act Hype Williams also shared some web space with him. The duo of Dean Blunt and Inga Copeland had been bubbling in the underground music scene for a few years prior, providing writers plenty of material, including a consistent flow of outlandish claims during interviews, music videos filmed on shitty web/phone cameras, and damaged tracks that, at times, sounded like they were recorded underwater.

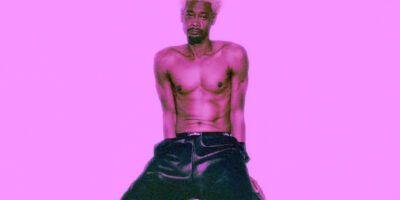

While it’s hard for an artist to be simultaneously plugged in to the world of Online and hold a level of mystique these days, The Weeknd and Hype Williams were balancing it effortlessly, and it helps to have broken through towards the end of the Wild West days of the Internet. But while The Weeknd would eventually trade his mystique for pop music stardom, Hype Williams weren’t interested in that. They continued to march to the beat of their own drum, with their live shows becoming increasingly absurd as their profile rose, culminating in 2012’s BLACK IS BEAUTIFUL, released under their own (stage) names. BLACK IS BEAUTIFUL is a key release for the genre now known as hypnagogic pop, but it’s also the last full-length Blunt and Copeland would make together (though their last collaborations would be featured on Blunt’s forthcoming solo works).

THE NARCISSIST II, Blunt’s proper solo debut, very much felt like an extension of BLACK IS BEAUTIFUL’s sonic palette, as a hazy fog clouds most of the album, with Blunt’s distinctive baritone (and at times poor, but compelling attempts at falsetto) cutting through the mist. Blunt’s voice was rarely, if ever, heard in Hype Williams’ musical output, as usually Copeland or uncleared samples took up the vocal duties when they appeared. And on THE NARCISSIST II, Copeland’s vocal stylings still clearly held a deep influence over Blunt, as when his voice did appear, it was usually him interpreting her unique and esoteric qualities. Similar to his later work, THE NARCISSIST II can be read as an explicit commentary on what was happening in hip-hop/R&B at the time, with the entire album being framed around samples from Ashanti’s “Rain On Me” music video about an abusive/toxic relationship. While tracks like “Caught Feelings” and “Galice” feel like (great) continuations of Blunt’s previous work, ironically enough it’s the track that actually features Copeland where it feels like Blunt has found his own voice the most. “The Narcissist” is just a complete stunner, as the Julee Cruise sample, Copeland’s hook, and Blunt’s deeply sad crooning all come together beautifully in ugly fashion. And it’s in “The Narcissist” that Blunt found the blueprint for his next record.

—

I went through my first real breakup in 2015.

It was classic high school drama stuff, involving cheating and friend groups falling apart and numerous grievances reached their boiling point. This is shit I worked out in therapy years ago, and got over in time as I and all parties involved eventually grew up and made our peace with what happened.

But in the fall of 2015? I was not at that point. I was still very much not over getting cheated on and then subsequently gaslit about being cheated on. And that’s where THE REDEEMER found me when I discovered the album and Dean Blunt. I didn’t know how to cope with my depression back then, a fact that left me feeling emotionally empty more often than not. It’s in that emptiness where I felt such a unique kinship with THE REDEEMER. I came to this album completely blind—I took it all at face value. Here was this guy, just like me, going through a messy breakup where both parties were at fault and attempting to piece together what happened in the fallout. While cryptic at times in its words, emotionally it was all so clear to me.

Take “The Pedigree,” the album’s first proper track. On the sudo-opener, we’re clearly hearing Blunt trying to tough it out during a proper breakup, but by attempting to mask his feelings he begins to recognize that he’s going to make the problem much worse for himself. But he can’t stop himself—he’s emotionally incapable of making that happen. He can tell himself that he’s happy to still be friends, but there’s underlying resentment still lingering as the song’s synthetic strings and bass-heavy drums fill up the mix. As I went through a few more breakups over the years, I found myself in THE REDEEMER more and more. But much like Blunt on this album, I wasn’t finding actual self-awareness, I was only performing it.

—

Released on May 1st, 2013, THE REDEEMER split most critics. Retrospectively you can see that while bigger publications (like Pitchfork) have eventually come around to Dean Blunt in the decade since, they weren’t there at the beginning. And it’s understandable why they took so long to get there. Unless you came in relatively blind like I did to his whole deal, you’d be forgiven for being unable to take THE REDEEMER at face value. Here was a guy who, up until this point (and also well after), was a troll. While a part of Hype Williams, he claimed to have joined the Nation of Islam, been pals with Cam’ron, and sold apples with USB sticks inside them—among other publicity stunts. And considering he always kept his guard up with music journalists, it’s understandable why people would assume the worst. Curiously enough, one of the few times he let his guard down in an interview, and the only time during THE REDEEMER era, was with the Russian magazine Афиша, who premiered his follow-up mixtape to THE REDEEMER, STONE ISLAND. While in an interview with FACT, he alluded to the fact that THE REDEEMER is about his and Inga Copeland’s breakup (“Inga was the only opinion that mattered, ‘was’”), he practically confirms it to Афиша (via a rough Google Translate):

Афиша: All right, let’s get down to business. Tell me honestly, THE REDEEMER is all about Inga Copeland, the second member of your former band Hype Williams, and your parting with her?

Blunt: Well, it’s more about how our life works. The fact that each of us is both a victim and a perpetrator of the situation in which we find ourselves. A hero and a villain at the same time, you know? And what happened to me, what happened, is kind of like a common thing. And, okay, what is there to invent – about her, of course. About us and her and about all this crap.

Like most things Blunt tells interviewers, it’s best to take this information with a grain of salt but it’s the most concrete information we have for the inspiration behind this album—not just about the breakup itself, but also about the many ways one could interpret the title of THE REDEEMER, as it could be about a man looking to redeem himself in the eyes of his former partner. Was this a man trying to redeem himself in the face of failure? A man trying to redeem himself in the eyes of a father or religious figure (“Father, protect me” is most prominently heard in the track “Walls of Jericho”)? In the same interview with Афиша, Blunt pretty plainly states that this search for redemption is a losing battle:

Афиша: Are those folded palms on the cover yours? In a metaphorical sense, of course. So you really sought salvation in music?

Blunt: Salvation is pretty self-absorbed, don’t you think? Which, moreover, has long turned into another tool in the hands of those who benefit from our egoism. So the very idea of praying for salvation is not so pure. It’s not that I specifically wanted to dig into all this on the album, but I think it’s about that too. In fact, with the cover, everything was like this: I needed some kind of picture suitable for the occasion, and I found it – then you can say and think anything you want. Palms and palms.

Афиша: You somehow didn’t give the impression of a particularly reflective person before, but now you openly say that praying for your own salvation means, in essence, lying.

Blunt: Not certainly in that way. There is nothing wrong with the very desire to be saved – at least I do not presume to condemn it. It’s just that the concept of salvation has gone into the wrong hands. And the owners of these hands quickly realized that selling their ideas under the guise of saving them is much easier than doing anything else. Those at the top, at all times, have needed a way to feed the beast that sits inside each of us. These are pretty obvious things, though. And to be honest, when I was recording THE REDEEMER, I wasn’t going to build these thoughts into some kind of artificial concept that would later help its perception. Just took and made an album. Which I don’t even listen to, so who the hell knows what kind of ideas are sticking out of it. For me, this album only made sense when I was making it. And then he lived his life, and I lived mine. I even sold the equipment that I used on it.

—

When Blunt speaks of redemption in the wrong hands, I know exactly who he’s talking about.

Me.

He’s talking about me, and plenty of other men who have wronged. There are men that seek redemption for the things they’ve done for entirely selfish reasons, with no real attempts to self-interrogate their behavior and actions, only doing enough so that they can continue on with their lives with little interruption. These men are performing the act of being a better person, with a heart and mind still full of hurt that’s waiting to be released.

When I initially sought out counseling for the first time five-or-so years ago, I was doing it as much for me as I was for my closest friends, who finally hit a boiling point with the ways my depression was manifesting. My friends knew the path I was going down, and wanted to steer me away before it was too late. Every day of my life, I thank them for finally giving me the push. Within a session or two, I was a complete emotional wreck, releasing over two decades of pain and hurt from my romantic woes, familial neglect and other traumatic events in my past that I was finally beginning to process. I don’t know where I’d be without these initial counseling sessions. Probably somewhere bad.

By the time THE REDEEMER turned five, my relationship to the album had changed completely because of my time in counseling; not only was I unpacking my depression, but also working through the internalized misogyny I possessed growing up as a teenage boy. No longer was I taking this album at face value. Instead I was processing it as an album depicting a man who did not deserve redemption despite so desperately seeking it. It was still an album about a toxic relationship, but our subject was so clearly the main intoxicator.

Before, I related wholeheartedly to a song like “Brutal,” with its deeply spiteful feelings and lyrics:

“When you recall my name, I’ll never be there, yeah

You gave your ass to someone else

You think you’re better off, yeah

We can’t evolve

‘Cause you have gone away and I’m still here

Girl if you see my face, I’ll die to be there

You will fall from grace without me there

And I will find my place without you here”

But suddenly I was trying to move past that. While I couldn’t take away the pain and anger I felt about my past relationships, I could strive to be a better person. A better partner. But of course I fell into a trap. In 2015 I wasn’t ready to seek redemption. I wasn’t in 2018 either. To speek vaguely, eventually I hit a breaking point, getting into a fight with someone I cared deeply about. It was a fight that was caused by my actions alone—I could no longer blame anyone but myself. I knew better, but I didn’t act like it. Face to face, I had to confront the fact that my actions had consequences, and those consequences caused deep, deep emotional pain—pain that I could not bear on my conscience any longer, and pain that I wanted to erase from this person I cared about. And naturally as I reflected on this time in my life, I too reflected on THE REDEEMER.

—

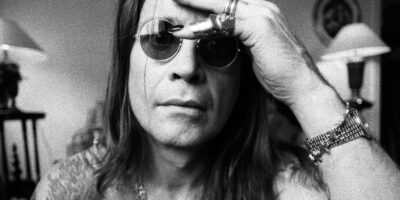

It’s tough to talk about THE REDEEMER as a standalone album, and not just dive into Dean Blunt’s discography at large—the musical motifs, themes, lyrics, vocal stylings, sample choices, and songwriting of this album set the stage for Blunt’s solo work to come. Even as he moved away from the more soulful, R&B and onto indie rock, sophistipop, folk, hip-hop, dub, noise, experimental jazz, and, yes, R&B again, so many hallmarks of Blunt’s unique and singular voice as an artist trace themselves back to this record. One hallmark in particular is the way Blunt uses samples and his motivations behind them. THE REDEEMER samples pop heavyweights like Kate Bush, Mariah Carey, Pink Floyd, and Fleetwood Mac throughout, taking pieces of their work that in the hands of a different producer would be too obvious. Blunt is able to place each in such a way that makes them his and his only. On the title track, Blunt samples Fleetwood Mac’s “Oh Daddy”, the deepest cut on RUMOURS written and sung by the late, great Christine McVie. In the great pantheon of breakup albums, RUMOURS might be the breakup album when we talk about the greater pop music canon, as its songs are as legendary as the stories behind them. (And I just have to mention that on this song, featuring an extremely obvious sample from a prominent pop album, there’s another sample of Puff Daddy towards the end of the track, the producer most associated with extremely obvious pop music samples.)

But in sampling a track from RUMOURS, a breakup album written by the all the people breaking up with one another, Blunt taps in Inga Copeland, the person he’s actively breaking up with. THE REDEEMER has a dreamlike quality to it, with this track being one its most vivid-yet-surreal dreamscapes, and for the first and possibly only time we hear a little bit from the other side of the story. While the voicemails we hear on tracks like “V,” “Dread,” and “Predator” could be interpreted as being left by the woman this breakup is about, I just can’t really interpret it that way. Rather, the voicemails we hear indicate that this woman is the rebound for Blunt, and his inability to move on and defend his new girl causes even more pain and hurt.

When you’re in the midst of a breakup, especially one you aren’t able to get over, time no longer feels linear. Some days are better than others, as you find yourself less prone to reflecting on the past, but other days it’s hard to get anything done other than look back on every mistake you or this other person made in the relationship as you try to get to the bottom of what ended this relationship, and what could have been done to fix it, if anything. And in this reflection, we get one of the album’s most standout tracks, “Papi.” Blunt croons over a sample of Pink Floyd’s “Echoes” as he repeatedly exclaims to his former partner that she brought out the best of him. While he claims this isn’t about re-litigating a possible reunion, it’s a pretty obvious guilt trip, as if you love and care about this person, why wouldn’t you want them to be the person they could be, in spite of yourself and your needs?

But with its big pop music samples and use of orchestral instruments throughout, there’s a certain cinematic quality that THE REDEEMER takes on, as while its storyline isn’t totally linear, its flow certainly feels that way. This cinematic quality is something Blunt himself directly stated about the album, per this excerpt with his interview with WIRE:

“‘But does anyone fucking mean heartbreak?’ Blunt bursts. ‘It’s all there: is it the heart? is it ego? Is it pride? Is it the same thing? The heart is the soul, everything happens in the same place, they are all the same thing, they aren’t detached. Nothing’s heartbreak. Everything is a film for a minute.’ Some kinds of heartbreak can last a lifetime, I counter. ‘A heartbreak is a film for a minute,’ he insists. ‘Because we all go through the same things, even in a different order and to different degrees, but we all have the same experiences. I just think it’s a film. I think it’s beautiful to look at it like that. Life as a series of, like, four films or something.’ Doesn’t seeing life as a film feel somewhat detached? ‘No it doesn’t.’ he argues. ‘I think it makes you enjoy it. I don’t mean four films with completely different storylines, I just mean reasons and seasons and things.’”

If you’re wondering if this is supposed to clear some things up about THE REDEEMER, it probably doesn’t because I can only barely get what the fuck Blunt is talking about here. What I can do though is interpret him wanting to detach himself from reality, and turn the pain of what he’s going through into art. THE REDEEMER isn’t about Dean Blunt’s breakup with Inga Copeland, it’s about the film he’s created in his head about his breakup. I can’t help but think about Steven Spielberg’s THE FABELMANS, where in one of the most pivotal scenes in the movie Sammy Fabelman, aka Spielberg, imagines himself filming his parents announcing their divorce to their children as a way to detach himself from the traumatic moment he’s currently living in. For Spielberg and Blunt, it’s easier to fictionalize your trauma than deal with it head on.

—

Over the last decade, THE REDEEMER has been whatever I needed it to be.

When I first discovered it, it was a breakup album about a rough and, at times, toxic relationship. A few years later, it became a breakup album about a toxic, possibly abusive, ex-boyfriend coming to terms with the end of his relationship. Later on, it became a breakup album about the state of R&B at the time of its release. Hell, it remains a breakup album about breakup albums. The great thing about THE REDEEMER is that it’s all these things. It’s become important to me because of how malleable it is. Whatever you give THE REDEEMER is what you receive in return. If you come into this album not being able to take Blunt seriously in a career full of trolling and publicity stunts, then in return you’ll receive a mess of a record you’re unable to let compel you. If you come into this album hot after a breakup, you’ll receive a record that sees your pain and projects it right back at you in all its ugly glory. And if you come into this album looking to get inside the mind of a bad guy, you’re rewarded with a compelling character study and a superiority complex. This versatility has followed me. And that’s why it’s my favorite album of all time, because sometimes an album has to be able to always be able to meet you where you are.

Comments