There’s a movie I recently learned about called SLEEP DEALER, about an imagined future labor economy in the US. It’s specifically engaged with Mexican bodies and the history of undocumented Mexican migrant labor that is required to sustain the country’s agricultural infrastructure. In this future, Mexicans are connected to machines and conduct the labor from the other side of the border, with their actions transmitted to machine bodies in the US. It’s an example of the idealized migrant labor force, one that is able to exist outside of the country without any access to the fruits of their labor (quite literally in this case).

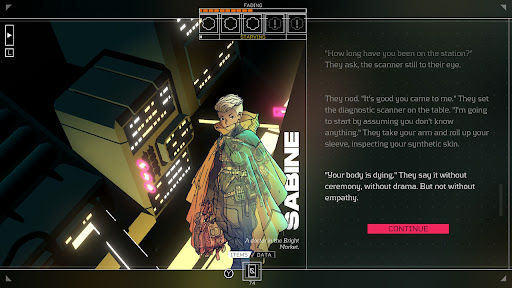

The 2022 multiplatform game CITIZEN SLEEPER starts from a similar set up. You play as a “sleeper,” a sentient robot whose consciousness comes from someone signing their life away to work for a corporation called Essen-Arp. They’re placed into a pod and have their consciousness transmitted to a robot frame to be able to more efficiently work without harming their physical form. Think a mix of THE MATRIX and Apple TV’s SEVERANCE. What makes CITIZEN SLEEPER different from SLEEP DEALER as well as those other popular depictions of evil capitalist corporations, is its emphasis on looking around instead of up. Instead of highlighting the horrors of capitalism and the required destruction of it, CITIZEN SLEEPER is more invested in the flashes of freedom that happen during all the shit.

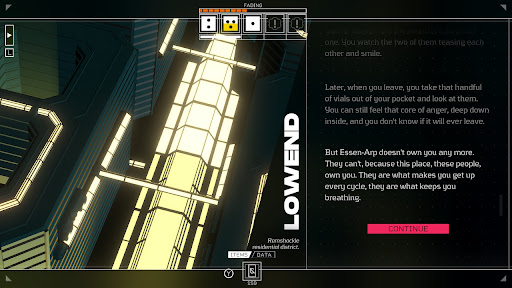

CITIZEN SLEEPER is a resource management JRPG/visual novel where you juggle making money, staying alive, and helping out various characters you meet during your stay on the space station of Erlin’s Eye. After picking your class (which as far as I can tell only changes your character art and a very minor stat difference) and a brief stowaway backstory, you are introduced to the flow of the game.

You have three things to worry about: Money, Hunger, and Condition. Money is required to buy food, medication, quest items, access to other parts of the space station etc. You can come across items through other means, but the most reliable is purchasing them, making money critical to staying alive and advancing questlines. Your hunger meter is pretty self-explanatory; it gradually goes down with negative outcomes or after sleeping, and you have to consume food or drink to get it back up. Being hungry leads to a worse Condition, which has the most negative effects on your ability to move forward. If your condition gets too low, from not eating or negative outcomes from a bad roll, you have less actions available to you each “cycle” (day). The amount of actions available to you is denoted by dice, with the max amount of actions possible being six if you sleep in good conditions and aren’t hungry.

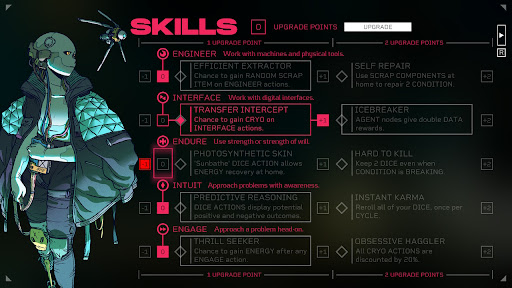

Presentation can be overwhelming, but really its just five attributes with five levels each.

Now let’s get to the dice rolling. This game is also an RPG, meaning that your character can level up and invest in different stats. You level up by completing quest lines, which can sometimes take a while to see through. You might want a character with a better “endurance” stat, which would mean more manual labor type actions become easier, or you might build towards an “Intuit” focused character which allows for an easier time with actions pertaining to deciphering or making sense of things (and a cool ability to predict how outcomes will affect your stats, highly recommend this). Each option you can roll for has a certain stat connected to it, meaning that if you have invested more in that stat, you may receive a boost to your roll.

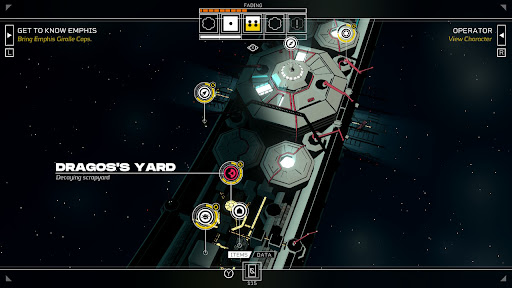

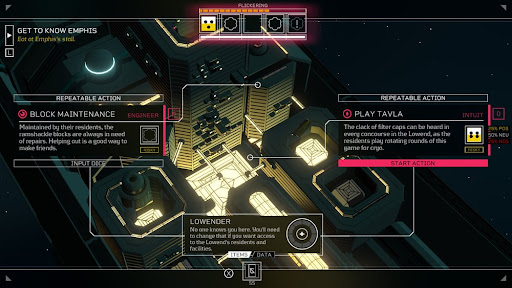

All this can feel like a lot to keep track of, and CITIZEN SLEEPER doesn’t do a great job of explaining this past a couple tutorial screens, but the RPG mechanics aren’t in depth in a way that you could create a “bad” build or anything like that. Skill upgrades can make things a lot easier, but you’re never locked out of a quest or ending because of stat requirements so it’s never too stressful. It really takes a couple cycles to realize what’s happening, and you slowly start to get into a routine. You wake up, see how many dice you got today and what numbers they are, pick a node on the overworld, and choose between one or two options to roll on. Some are for money, some are quest related reconnaissance, and some are just for buying items. And that’s sort of the game: wake up, pick a node, roll a die, repeat, sleep. It’s all a very clean and clear metaphor about both the mundanity of everyday life, but also just how much upkeep it takes to keep going without ever really knowing how you’re gonna be doing the next day. As you successfully and repeatedly complete tasks, the map starts to open up, you’re introduced to more characters and more quests become available.

Erlin’s Eye is a big ring you veeeerrrrrry slowly slide back and forth through everyday

It never felt good maneuvering the overworld map; I’m sure that clicking with a mouse on nodes works much better than jumping around with a directional pad. Fast travel or a menu instead of slowly scrolling back down the map would have helped a lot. The gameplay and systems can feel a bit overwhelming at first, and it took me a couple hours for it to click and start to feel like I was working towards something rather than aimlessly clicking on actions. At times it can feel difficult to know what you should be focusing on, since there is no real “primary objective,” but I naturally started following some quests over others. I came across objects I needed for other quests naturally too, making them easier and quicker to complete; I’d come across an object and not know what to do with it for hours only to realize it was for this later part of a quest I had access to from the beginning. You settle into a flow and then the game starts to click in a way that becomes very satisfying—I’m not sure if I just got lucky, but by the end of my five or six hours of the game I found it very easy to consistently have my stats maxed out and receive a constant flow of cash.

Options can result in a Positive, Negative, or Neutral outcome. Both Positive and Neutral outcomes count as successes, so most of the time, its likely you’ll be making progress at least.

While the gameplay is relaxing in a strange way—checking off tasks in a list—the subject matter offers a lot to think about. CITIZEN SLEEPER is very invested in the body. In being in a body, but not always being comfortable with it. Of being in your body but it not being everything about you. Of having and not having a body. Your character is a sentient robot, a machine body that is carrying someone’s consciousness. The robot version of you never signed up for this, though, and chooses to escape their life of labor in search of freedom and something better than what was forced on them.

Throughout the story, your character wrestles with what it means to not be in their own body, what this body means as the only one they have access to, and what responsibilities they have to their old physical self. If your other body is still out there, what role does this one play? How much autonomy do you really have over your body if it’s tied to things like food and medication, both of which you need to earn money to acquire, which then means giving up your body to certain types of labor? In this way, the game opens itself up to a multitude of readings from critical race theory to disability studies. Marxist bros can latch onto its depictions of an evil corporate capitalist system that literally owns the laborers’ physical bodies, and those invested in gender queerness won’t be able to not relate to the body dysphoria the main character occasionally alludes to. It’s a great text to think about, even if the thematic broadness doesn’t come to any strong conclusions either way about what to do about these feelings and anxieties around bodies—maybe that’s a strong conclusion in itself?

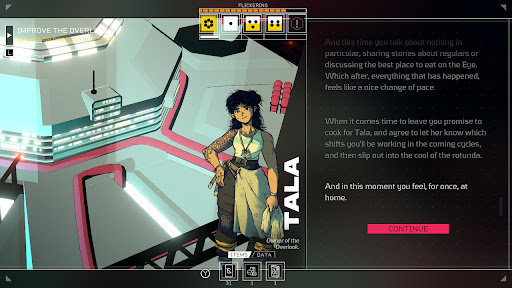

Slowly though, the game becomes less and less invested with your singular experience of yourself, and it begins to recognize how the body is not alone in these more philosophical questions. All the characters you meet on the Erlin’s Eye also demonstrate a lack of ownership or control over their own bodies to some extent. Many characters have cybernetic limbs that must be recharged or updated to continue functioning, others are entirely bio-organic but may struggle with addiction. One character is a foster parent to a small child, and his body is no longer just his and his employers, it’s also now responsible for maintaining the life of another. Another character is the child of immigrants, whose body is the representation of an entire population of people and culture, and can be seen as an invitation for discrimination and hate crimes by the people around them. There’s even a rogue AI being hunted by a totally different AI that asks you why you are so invested in your physical form to begin with if it doesn’t belong to you.

And these are just the characters whose stories I saw through to the end. I’m sure I missed out on a couple in my time with the game. In this way, the game shows us that while we may have one relationship to a body, most people are also struggling with the responsibilities of being in a body as well. The game doesn’t ever make one scenario feel less serious than the other, and through exposure to the various difficulties of these other identities, you can’t help but feel less and less alone in what originally seemed like a dystopian space station with nothing but suffering.

Throughout my stay in the station I saved a neighborhood from corporate surveillance, aided in an assisination, almost got myself assassinated a couple of times, opened a bar, and also shared stories with a man who I bought mushrooms from everyday. There was never a dull cycle, and although at times it could feel repetitive, I always felt like I was making progress no matter how little I did at a time. Some days I got handed bad die, and I had to avoid harder, “quest progressing” options, but that also allowed me to instead hack some terminals for data that I could then sell for money.

Slowly making my way through characters’ stories felt rewarding narratively, hearing about how people ended up here and what hope they’re still holding onto at the end of the day. Every finished quest line felt like a satisfying ending to the game, like I could put the controller down having felt like I got a full experience. That’s where CITIZEN SLEEPER was the strongest for me, when it began to make space for the utopic in all that dystopia. The game recognizes that in all this anxiety and dread, there are still flashes of light. It comes to the radical truth that actually “Capitalism” isn’t everything, and if we let it be, and feel like it’s everything, then we’re taking each other and ourselves for granted just as much as these nefarious corporations do.

We can still care for each other when the institutions around us don’t. Sometimes it takes other people to recognize our value in order for us to do it. It’s easy to take ourselves for granted sometimes, when we exist within a system that only values our labor and what our bodies can do to generate profit. That other people care about us can make us care about ourselves too, and keep us going. Some days are easier and we don’t question the routine of it all, or how much better things could feel. And there are days where getting out of bed feels much harder, and we aren’t as happy with the bodies and lives we’ve been dealt. CITIZEN SLEEPER emphasizes that there is so much life outside of just our own experience to value, and to be valued by. We aren’t in this alone. Capitalism sucks, but we don’t have to.

Comments