The last significant event that happened to me before quarantine was a trip to Minneapolis to see 100 gecs perform live. It was with two of my best friends. The three of us get to see each other once a year if we’re lucky, and each time it’s a raucous ol’ jaunt with the pals, playing mini-golf on a southern New Jersey boardwalk or throwing back beers, balking at the huge donk on the titular character of THE BOSS BABY. What better way to reunite this year than at a 100 gecs concert? Of course, the show did not disappoint (except when Laura announced “special guest” Charli XCX and then laughed at the crowd’s gullible cheers). My turquoise eyeliner melted off, Micha’s glasses broke and disappeared, and Thomas sweated his vermilion 7-Eleven bowling shirt to a beautiful, wet maroon. And to think it only lasted about an hour.

I could gauge my ecstasy by a rare willingness to succumb my own body to those moshing next to and into me. As a professional dancer and Pilates instructor, I am overly conscious of the sacredness of our bodies, and therefore terrified of getting physically injured. But the attitude at a gecs concert is one of mutual respect and fun—we’re all here for a stupid good time, and that can’t happen unless everyone is safe to some degree. On more than one occasion, I witnessed a wall of people coalesce around one person, low to the ground, tying their shoes under the light of an iPhone flash. At a particularly physically boisterous moment, Thomas—an expert at moshing and built like a dam—shielded a guy from getting body-checked behind us, who gratefully exclaimed, “This guy is my ROCK!” In the hot ocean of green-hairs and Minnesotan locals, I could entrust my own body to the waves of the whole. Minimizing anxiety is the necessary precursor to loss of inhibition, which is the necessary precursor to euphoria.

Bliss is increasingly difficult to access naturally these days, if not nearly impossible. So extreme is American capitalism in our time that we are forced to disembody ourselves in order to keep up with the “free” market’s demand for us to perform more work for less pay. Whittled down to a machine and humiliatingly commodified for parts to be sold on a LinkedIn profile, people living through the new millennium are alienated from their own sense of self more than ever. That is, unless it can be filtered through the reigning capitalist framework. With time, money, and energy absolutely depleted, there remains little opportunity for a person to cultivate a somatic relationship with oneself, a relationship without the constant stress of economic (in)security, and therefore little opportunity to show up in a realized, uninhibited mind-body state. So, plunging into the sanctuary of a 100 gecs show can mean a lot in these trying times.

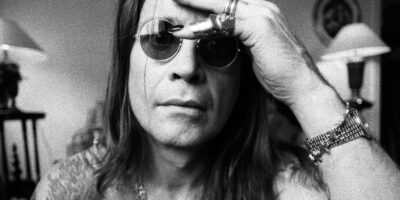

Hypnagogic pop musician/political science PhD John Maus has made a project of showing up in this way. His live performances are intense, bordering on primeval, as he wails and thrashes about the stage and jack-knifes the microphone into his head until he bleeds. He describes this stage performance as “the hysterical body.” It’s thoroughly uninhibited, and he has stated his mission with this is to “appear” to the audience—to achieve total authenticity on stage, the platform by which we are most inclined to behave inauthentically, because “that’s what we all really want, is to see one another and to be seen.”

—

I left my apartment in New York and ended up back in my suburban hometown in southern Idaho at my parents’ house during the start of COVID. Weeks passed with increasing existential dread until I about had a cabin fever-induced mental breakdown. Mind and body atrophied by Netflix binges, rapidly absorbing The Bad News via Twitter, and furiously refreshing the coder’s abomination known as the New York Department of Labor website—I decided that being sedentary was simply not an option while in quarantine. The necessity of movement was clear as the depravity of our crisis response.

As quarantine thickened, I couldn’t help but hunger for some modicum of presence, of mindfulness, of consciousness attached to my own biological occupancy amidst the monotony of unemployment and my parents’ house, endlessly scrolling between memes and the worst news I’ve ever witnessed in my relatively short Millennial life.

In an effort to reconnect with my mortal coil—the same one that was shriveling in an effort to evade permanent collapse by an invisible killer virus—I took an online Gaga/People class, based off the Gaga movement language developed by Israeli choreographer Ohad Naharin. The class is a mirrorless improvisation session in which the instructor suggests different somatic cues which guide the movement to be exclusively sensorial. You might be cued to move as if your body is a sandbag breaking open and spilling out, or to move as effortfully and agitated as possible before suddenly stopping and “floating,” enlightening yourself to gravity’s forces and the body’s own tensegrity against those forces. Above all, the major emphases of Gaga movement are to return to pleasure and to connect to groove—universal movement experiences regardless of training or technique. It’s like meditation, but your body does the thinking.

The urgency to move from uninhibited, internal impulses has bled into every calendar-less day. I stopped giving a shit about every way I had been trained to move and to be witnessed as a subject of performance for the past 22 years. Alone in the house, the walls shook as I blasted Gwen Stefani’s LOVE. ANGEL. MUSIC. BABY. and threw a dance party for one. I writhed on the porch when it began to rain until my body craved its own nudity against the hot sky’s downpour and I took all my clothes off. I screamed at the top of my lungs, just because I could. I decided to take up space with myself; I decided to be in corporeal conversation with her for utter want of stimuli, something that wasn’t just the endlessly maddening, dissociating, apocalyptic news cycle; something that I could control if I wanted to.

Moving became essential, and not necessarily as an outlet for my emotions, or as a way to make sense of the world, or to get my “steps” in for the day, or—worst of all—pay my bills. I had to figure out a way to do it without an audience. Without a stage to show up on, Maus’ philosophy falls short, and in fact ignores the meditative quality of “appearing” only to yourself, perhaps like the experience of a person getting thrown around at a gecs show. As quarantine thickened, I couldn’t help but hunger for some modicum of presence, of mindfulness, of consciousness attached to my own biological occupancy amidst the monotony of unemployment and my parents’ house, endlessly scrolling between memes and the worst news I’ve ever witnessed in my relatively short Millennial life.

—

Being home began to bring up the usual regressions that happen when you move back in with your parents. Just as I would hide in the computer room as a kid, I started spending nauseating amounts of time online again—partly out of boredom, and partly out of necessity. Certainly, I was contacting friends via phone, text, and Zoom, but generally the only way I could feel “involved” with the world at large was over social media. So, to the Internet I fled as my sense of self became increasingly outsourced to my online presence amidst the communities I yearned to be interacting with in real life. My despondence fluctuated as I shuffled between silly posts from my mutuals, misleading headlines from mainstream media outlets, and targeted ads for $28 organic silk face masks. The constant deciphering and compartmentalizing of information online is an emotional rollercoaster. But always, most reliably, what made me happiest was my group chat with Thomas and Micha.

The uncanny universality of all those samples was validating—it’s not just me whose brain is semi-poisoned by Online and the daily barrage of capitalistic marketing. It’s not just me who wants to laugh at it all and dance anyway.

For the last year, the group chat with Micha and Thomas has included a sporadic event now deemed the Listening Party. We pick an album—new, old, good, bad, fascinating, silly—have a countdown, and press play at the same time. We listen to it all together, regardless of time zone, and engage in Facebook Messenger commentary. It began with a mutual listen of Nervous Cop’s sole release, a self-titled kitchen sink experimental rock collaboration between harpist Joanna Newsom, John Dieterich and Greg Saunier of Deerhoof, and Zach Hill of Death Grips. Since then, the albums have ranged depending on the mood or intrigue: Shakira’s LAUNDRY SERVICE, Lady Gaga’s CHROMATICA, Eiffel 65’s EUROPOP, Green Day’s AMERICAN IDIOT, System of a Down’s TOXICITY, The Aquabats’ MYTHS, LEGENDS AND OTHER AMAZING ADVENTURES VOL. 2, and Peppa Pig’s MY FIRST ALBUM, just to name a few. Sometimes it feels like going to a concert, but without needing to yell over the music to say to your friend, “I hope Skrillex enjoys a post-ironic revival,” or “Hobo Johnson Get Therapy Challenge,” or “Peppa Pig combining traditional march and folk musical elements with baroque-style choral lines and spoken word is really ahead of her time.” Music criticism is so easy.

And in that time there was, of course, Square Garden Music Festival. Imagine how cosmically aligned it was for the three of us to virtually attend a live-streamed event hosted and curated by 100 gecs in a Minecraft server with a lineup of some of the most colorful and Online musicians of 2020, a not-far-off extension of our Listening Parties. Although I was navigating between Twitter and a couple different group chats with friends, it was also a concert experience with over 12,000 strangers, only this time there were no bodies to rock and roll against, no light show to blind or speaker feedback to deafen, no turquoise eyeliner to sweat off or glasses to break. I didn’t even have an avatar—a body, so to speak—in the Minecraft server, so I was merely bearing witness to the mosh of pixels jumping up and down in a crowd-shaped formation. Whatever body contact would have occurred had Square Garden played out in person was transposed through the mutual recognition of all the jingles and memes and mid-2000s viral pop songs that stippled—nay, splattered—each set, amidst the avant-pop bangers we all came to hear. The uncanny universality of all those samples was validating—it’s not just me whose brain is semi-poisoned by Online and the daily barrage of capitalistic marketing. It’s not just me who wants to laugh at it all and dance anyway.

—

In 1998, music scholar Christopher Small introduced the verb “musicking” to the language of sociomusicology, proposing the idea “first that the essence of music lies in performance, and second that performance is an encounter in which human beings relate to one another.” He suggests the nature of music to be an action in which all participants in its performance give meaning to the music, no matter if they are on stage or not. What’s especially beautiful about his interpretation is the idea that music is a function of modeling and building relationships through the communicative string of gestures we know as ritual. He writes:

“Each of the activities that we call the arts is a fragment of the great universal performance art for which the only name we have is ritual. Each is a way in which we use the language of gesture to affirm, explore and celebrate our concepts of how we relate, and should relate, to ourselves, to one another and to the world. In taking part in those activities we think with our bodies, and we make no separation of body from mind. I should go so far as to assert finally that all art is performance art.”

Sitting behind a screen with headphones on full blast could never replace the sensation of being at a live performance. Obviously, there’s much less movement involved aside from your fingers rapidly firing hot takes across the keyboard, and probably some light headbanging when “Scatta” by Skrillex starts playing. And yet, from the beginning, I’ve loved the unique pleasure of experiencing music through these Listening Parties because it enriches my relationship both with my friends and with the music itself. It almost makes more sense to listen to 100 gecs this way: music produced on a computer and emailed between two people in different places, Dylan Brady in LA and Laura Les in Chicago, who sing about the loneliness of cell phone attachment. Somehow, in this way I can briefly override the disembodiment of being sedentary and online, and the identity I’ve transplanted out from my body and into the Internet is still able to translate back to me a sense of spiritual fulfillment.

100 gecs take popular music from the last 20 years, throw it all in a pressure cooker, and let the lid blow off—a rebellious act in an era where so many of us wax nostalgic for the media of our youth, those so-called “simpler times” when the words “subprime mortgage” didn’t make sense.

I wonder what Small would say about our funny online concerts in the era of COVID-19, and how the music coming out of them couldn’t be so without having absorbed the socioeconomic structures and power relations in our society. In his work describing musicking, he frames the question of meanings in performance by asking: “What does it mean when this performance takes place at this time, in this place, with these participants?” In response, certainly Small would have agreed with this musing of John Maus’:

“I believe music is part and parcel with the kind of structures of power at any given time…romanticism was perfectly part and parcel with the bourgeois individualism . . . and of course the renaissance and medieval music was perfectly part and parcel with the church as the dominant structure of power. So, today, the dominant structure of power is capital, capitalism, global capitalism, so music takes on this commodified quality, and it answers to that and to that alone. But if we want to enter in a conversation with those pieces, with those works, we have to do it through our own objective, historical moment, using the vernacular—which is, as far as I can tell, pop music.”

What is so endlessly fascinating about 100 gecs and the community they’ve built around their music is that they could not have existed in any context other than ours right now, and that what their music consists of is almost exclusively a regurgitation of American Millennial-Zoomer culture. They take popular music from the last 20 years, throw it all in a pressure cooker, and let the lid blow off—a rebellious act in an era where so many of us wax nostalgic for the media of our youth, those so-called “simpler times” when the words “subprime mortgage” didn’t make sense. Rarely does a 100 gecs song breach a three-minute runtime, and within that time it could very well shift gears twice or thrice so as to feel like a totally different song has begun playing. You might even call it a reflection of what it’s like to have “Scrolling Brain,” an ailment caused by being bombarded with corporate content that is constantly competing for our attention. At least it sounds so fucking catchy.

This affliction explains the cathartic mania of 1000 GECS AND THE TREE OF CLUES. An album of almost entirely remixes, TREE OF CLUES makes reference to its own references, a feedback loop teeming with knowing playfulness. By now I’ve listened to its parent LP hundreds of times, its 20-minute length perfect for a drive to my part-time minimum wage retail job last summer. Fortunately, the remix album breathes an entirely new life into each and every song, a clear indication that, at its core, the original tracklist contains solid pop structures. By staging remixes executed by the very artists and styles that influenced its predecessor, TREE OF CLUES is a reflection of a reflection of a reflection. The pop punk pining of “hand crushed by a mallet” fits like a glove on Fall Out Boy. The cheeky twee pop of “ringtone” balances with the sweetness of Kero Kero Bonito and Charli XCX, the compressed grit of its ending leaning well into Rico Nasty’s rowdy trap. Estonian rapper Tommy Cash pushes “xXXi_wud_nvrstøp_ÜXXx” deeper into its MDMA’d inclinations towards Euro-trance music, with its bubblegum bass outro performed by Hannah Diamond. “800db cloud”’s industrial bent is thrust into Ricco Harver’s brostep extreme. These are only a few examples that prove that all the elements of these remixes were already there, and in fact influenced 100 gecs to begin with.

This all probably doesn’t mean anything to you if you dislike 100 gecs. It’s noisy. Yet that’s why they resonate so much with me. Not only have the duo captured pop in its essence at the center of every online microgenre to emerge and fade in the past 10 years, but they have also compounded it upon itself to tease you towards its collapse inside a milieu that’s only discernible if you’re scholarly or psychotic enough to break it down into parts. It’s safe in its thick pop familiarity, but layered on top of itself enough times over to transport the listener into an alternate dimension, which is the least I could ask for if I’m going to give all this brain space to discriminating between different propagandas and seeing up to 10,000 advertisements a day.

—

The other night I was home alone again and I played TREE OF CLUES over a loudspeaker. I was trying to help myself write this piece by drinking a bottle of pinot grigio. Before I even wrote anything, it turned into another solo dance party, scaring my cat with ear-obliterating volumes of poptronic music. I sang along loudly. I ran around the entire house. I danced and danced and danced. I felt myself inside my body, reclaiming it from the pieces that get uploaded, compressed, and posted to the Internet. Finally I can understand it a little more; it’s not all nonsense, not just wasted hours online. Through the digital information stored inside of me, I can reference past parts of myself. “What does it mean when this performance takes place at this time, in this place, with these participants?” The umru remix of “ringtone” played, the muffled vibration of a cell phone ringing inside a backpack underlining most of the song. It’s never really gonna go away. At least my body is still here.

Comments