Apichatpong Weerasethakul—or referred to by Western audiences with inflexible tongues as “Joe”—established his name in the arthouse canon by making enigmatic slow films. A lesser known truth: Weerasethakul is also gay. The fact that many are unaware that one of cinema’s most potent voices is queer has much to do with the Thai director’s lowkey sensibilities; unlike the icons of New Queer Cinema, Weerasethakul is not one to indulge in flamboyant excess, or even center his sexuality in his work—in other words, he may be gay but he doesn’t make “gay films.” An exception to this pattern is Weerasethakul’s fourth full-length feature TROPICAL MALADY. Released in 2004, the film is a rare gem in his oeuvre that explores queer desires in a reimagined Thai landscape.

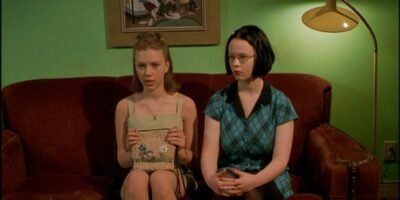

Syntactically structured after the term “magical realism,” the film is bifurcated into two. The first half occurs in the Real and traces a budding relationship between Keng (Banlop Lomnoi), a handsome soldier posted in a rural city, and a village boy named Tong (Sakda Kaewbuadee). The two meet after Keng assists Tong’s family harvest and, shortly after, they fall in love. Languorous long shots frame their sweet courtship as it unfolds through shy glances exchanged across the table, nervous touches between skin, giggles shared on a market voyage, and light petting at the movies—a meta nod to the historical overlap between cinema and cruising.

What is especially striking about TROPICAL MALADY is the way queerness is naturalized. Tong and Keng experience intimacy with such uninterrupted tenderness that it is hard to fathom that the film is set in a country where LGBTQ+ rights are marginal. But Weerasethakul’s Thailand is not one where queerness is situated on the outside—as it is in reality—instead a world where being gay is mainstream: a reimagined universe where non-normative sexuality doesn’t come with fatal social and political baggage. Hence, why when the two hold each other in public, or when Tong strokes Keng’s hair in daylight, there are no furled fists or cruel slurs spat out by passengers, as one may typically expect in this context. Their relationship is a part of the ordinary, the collective, the assimilated. TROPICAL MALADY is, then, not a typical queer story where homosexuality—and all the pain, torment, and anguish of being outcasted—is the central axis of action. Instead, what we see is the orderly gait of desire: the regular rituals and routines that propel coupling. Except, here, the lovers just happen to both be men.

The timeline of Keng and Tong’s romantic development is scrambled by a heavy use of elliptical editing. Scenes often feel out of place—disjointed—as if there were holes in the narrative thread. Far from being a result of negligent filmmaking, this very vagary is a signature of Weerasethakul’s, whose modus operandi since his debut has always been to bend and play with the dimensions of space and time. As in 2002’s BLISSFULLY YOURS, TROPICAL MALADY is a film that confounds and is fugue, one that is perhaps best enjoyed in schematic surrender.

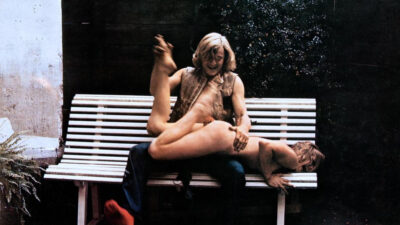

It is thus unsurprising when the film’s first act abruptly reaches its apotheosis. After Tong urinates, Keng lightly pats his lips onto his lover’s hand, covering every surface area of pee-stained skin with a soft kiss. The eroticism of his transgression is reciprocated by Tong who, subsequently, takes Keng’s palm into his mouth and gnaws at it with an uncharacteristic intensity. When the frame switches to a medium close-up of his visage, it becomes clear that something primal in Tong has awakened; once a blushing coquette, he now licks his prey with licentious hunger.

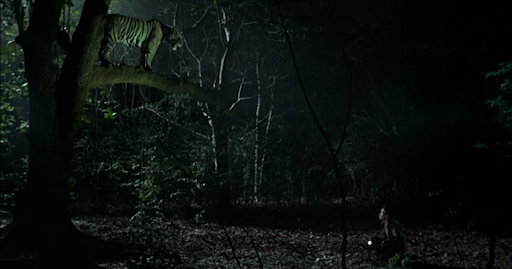

Keng’s beastial transformation coincides with the start to the film’s second half: an entirely new story inspired by traditional Thai folktales about a female tiger spirit who falls in love with her hunter. In Weerasethakul’s retelling, however, the tiger is embodied in Tong, and his brave suitor is once again Keng. Their relationship germinates in the thicket of the jungle, where the rumblings of fauna, the rustling of leaves, and the symphony of cicadas score their mutual affection.

There’s a focus on landscape in this sequence. Whereas the first half trailed after the couple, here, privilege is given to the lush trees that sway callously in the summer wind, or the dense bushes which seemingly never end. Captured in long shots, the human silhouettes seem insignificant against the overwhelming terrain: the body becomes a mere dot in this great, mystical world. What these images signify is an inversion of anthropocentric divisions. Infamously, cinema has propagated the idea that the world belongs to humanity, and therefore Mother Earth and her fruits are for man’s axiomatic use—think colonial documentaries or eco-horror flicks which vilify the organic world at the behest of modernists. Through images that make figures small and nature big, Weerasethakul’s frame defies this logic; the power dichotomies between natural and unnatural, human and non-animal, seem to blur in a hypnagogic daze.

This effect is fully realized in the film’s finale, a breathtaking confrontation between the spirit and the hunter. The two silently stare at each other until, finally, the tiger speaks: “Once I’ve devoured your soul, we are neither animal nor human. Stop breathing… I give you my spirit, my flesh… And my memories. Every drop of my blood sings our song.” Presumably, the invitation for fusion is accepted; as Keng and the animal are washed together, the partitions that delineate their physical world—such as the separation of bodies—and ones that shape our consciousness—such as homo/hetero, female/male—are erased. As the frame fades to black, the film inhabits a state of serene state of Oneness.

It’s been 20 years since TROPICAL MALADY was released. Back then, at the turn of the century, anything felt possible: the world seemed like ours for the making. Embodying this optimism, the film posits a utopian vision for the future where queerness is unconditionally accepted, and humans live in harmony with nature. Revisiting the film now, it is particularly chilling to realize that these dreams have yet to be realized. Reactionary discourse on LGBTQ+ communities plague the zeitgeist, and capitalists are still permitted to control and pillage any splotch of greenspace. Nothing has substantially changed in these past two decades. TROPICAL MALADY is thus, simultaneously, a touching experience and a hauntological one. Escapist at first, when the credits roll, the contrast between what could have been and what exists is so deeply depressing. How much longer must we wait for tolerance?

Comments