Best known for making vivacious, mind-bending works, Nobuhiko Obayashi’s realist films have tragically fallen under the radar. In the past few years, however, there seems to be a renewed interest in the uncut gems of his oeuvre. BEIJING WATERMELON, for instance, has been making its way around repertory theatres in Canada; Paradise Theatre’s Eastern Promises held a screening of its new 4K restoration, and earlier in July Vancouver’s The Cinematheque hosted their own. If you plan on riding the Obayashi resurgence, there’s few better ways to start than down the winding coastal roads of HIS MOTORBIKE, HER ISLAND. Memories are a lot like cinema in how they embellish and beautify reality. Ostensibly a pulp romance, HIS MOTORBIKE, HER ISLAND gets at the laconic, universal, and inexorable way our memories degrade: the way those frames start to fray and bend. And with every replay, the details—him and her, past and present, real and imagined, monochrome and colour—coalesce into their own, unique truth.

It’s 1986. Somewhere near Tokyo, a biker in blue jeans and a fitted leather jacket—conjuring an image of James Dean—zooms across the empty highway, careening past vistas of rice paddies and Minka buildings, wispy bridges and ever-expanding shrubs. His pose appears relaxed, carefree, elegant as he conquers every twist and turn. A modern-day cowboy, he has made the road his second home.

The biker’s name is Ko Hashimoto (Riki Takeuchi), the rakish protagonist at the center of Obayashi’s melodrama. Narrated by his future self, the film recalls a tragic summer romance between Ko and his jaunty, free-spirited lover, Miyo (Kiwako Harada). Remembrance is as much a theme as it is a formal framework here. To visually represent the act of recollection, Obayashi structures the film as a series of disembodied vignettes, some in colour, and others in black-and-white—the memories eroded by time.

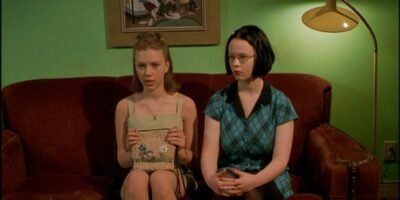

HIS MOTORBIKE, HER ISLAND begins in monochrome. Ko, a part-time accident photography assistant, part-time college student, has just broken up with his demure girlfriend, Fumiko, on the basis that all she does is cook and cry. He’s a bad boy looking for adventure: she’s too domestic. It is amidst this transitional phase that Ko first encounters Miyo. They flirt and exchange several rounds of banter on the side of the road. Although a mutual attraction germinates, their short-lived interaction is dismissed as another one of those “what if” moments.

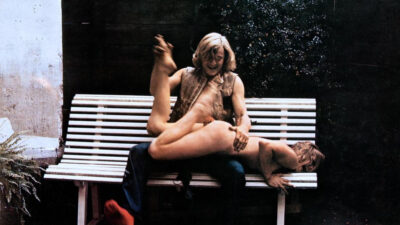

But if there’s one thing about Obayashi, it’s that he’s quite the romantic. Blessed by peripeteia, the two are eventually reunited while naked inside a bathhouse. Whereas the biker blushes, Miyo appears blithe to the sexual implications of the context. Without a hint of reservation, she freely displays her body while writhing around and stretching her limbs—much to Ko’s visual pleasure. Miyo’s sensuality is contrasted by Fumiko’s reserved temperament. As seen in a series of flashbacks, Ko’s ex-girlfriend is furtive, chaste, and extremely sentimental—which causes her to burst into tears before her deflowering. These are two women with completely divergent ideas of intimacy: one which is “free” and modern, and another that roots itself in traditional values. Miyo and Fumiko’s sexual chasm charts crucial socioeconomic changes occuring in the globalized ‘80s: a prosperous, blingy period which saw the integration of women into the workplace. Alongside the glass ceiling, hitherto notions of chastity were also shattered. The result was a new configuration of woman: someone as lubricious as she was luxurious.

Someone like Miyo.

Standing at this crossroad of feminine ideals, Ko ultimately chooses to be with Miyo. Their courtship is underscored by a mutual love for motorbikes, a motif embedded in every frame. Initially the automobile is a mere plot point that the characters converge on; however, as their relationship deepens, Miyo’s mild intrigue towards Ko’s Kawasaki W3 twists and turns into an erotogenic fixation. At one point, Miyo throws herself onto the bike with an expression of drunken pleasure, an affect that trumps anything expressed for Ko.

The libidinal charge of the engine has been explored plentifully in post-industrial cinema and literature—notably by J.G Ballard in the 1970s. Its voluptuous surface, mechanical grunting, steely fortifications, masculine girth, and speedy possibilities have possessed many fantasies of the contemporary subject; and indeed, there is nothing more modern than a sexuality which transmutes from the biological to the artificial. However, Obayashi’s depiction of mechanophilia is much more subtle than the transgressive writer’s. Miyo’s fetishism is implied rather than explicitly spoken, hinted at by her yearnful gazing and strange remarks. The depths of her desires will always be opaque, for this is a story told by Ko’s outsider perspective.

The Kawasaki holds a different significance for Ko. In a slightly out-of-place sequence, he and his bookish friend Keiichi (Ryôichi Takayanagi) put on workwear suits and take a violent joyride, knocking out headlights from passing cars that carry businessmen in tailored blazers. The scene is clearly an allusion to bōsōzoku, the biker gangs that dominated Tokyo in the 1980s. Rising out of a widespread disenchantment with post-war structures, bōsōzoku were composed of working-class youth—many of whom were employed in construction—that would flood the streets at night, revving their engines, wrecking havoc, and halting, literally, the flow of capital. For the bōsōzoku, the bike was a symbol of proletarian resistance against a stifling individualistic society. At the end of the scene, Ko and Keeiichi, two part time workers, disembark their vehicles with a similar pride.

Miyo’s prodigious talent for biking and need for speed deeply unsettles Ko who, from his job, knows all too well what end awaits the adrenaline junkie. Obayashi, who is criticized for his unagentic female characters, reverses the fate of his maiden here. Although Ko tries to restrict her primal urges, Miyo’s defiant; she steals his bike and ditches him—reversing his actions towards Fumiko—for a life on the road. There is a feminist explicative located somewhere in Miyo’s self-determination. If the motorbike is a vehicle that liberates men from banality, perhaps, then, for women, it is an escape from the tiresome impositions of men.

The film ends on an ambiguous note. In the penultimate sequence, we see the couples’ motorbikes vroom down a winding singular road, playfully zig-zagging around each other—the roadie tango—before diverging paths. Then, a background voice declares that a young woman has crashed her motorbike into a truck, which is followed by a coloured clip of Miyo’s mangled corpse. But a few moments later, in a black and white shot, Miyo reemerges alive and well. It’s hard to cohere if she died or if she evaded the grim reaper; what is real and what is simply a memory obscured by nostalgia?

Comments