For a month now, I’ve been playing a game of evasion. I work in a tiny cubicle in an industrial office located out in the middle of nowhere. My room sits without windows and I leave it maybe five times in an average eight-hour shift, usually to ask a question for five seconds or relieve myself in another, slightly larger windowless room. I brought in a nice pair of headphones to go with my MP3 player—a means of signal jamming my brain while I sort through hundreds of files for employees I’ve never met. For most of this time, either harmless nineties/aughts filler material or podcasts made up the bulk of my listening, white noise to befit my own mundane environment.

But the outside world has crept in.

—

I don’t need to tell you how bad things are, or give you something akin to the FIRST REFORMED “you will live to see this” spiel. They just are.

My tendencies, with art, just as my whole being, will always steer me towards the nearest available outlet for neuroticism. My brain will inevitably tell me to stare at Twitter for just long enough to see headlines that exacerbate the dread in me, and I will always take the records more suffused with paranoia, that which is louder, brasher in its fearful indulgence than the work that merely settles for a plainly anemic sadness of the moment. Straightforwardly speaking: the majority of music does not choose to rise to these sorts of emotions. That’s understandable, considering this sort of all-consuming dread or nihilism typically swallows up everything around it and doesn’t allow for much emotional flexibility. So I came to embrace niche genre fare; the skramz bands, the prog bands, the skramz prog bands—anything that sees the white hot coils of fear and takes hold until the skin singes. In recent times I’ve come to two records that have best enabled this of me.

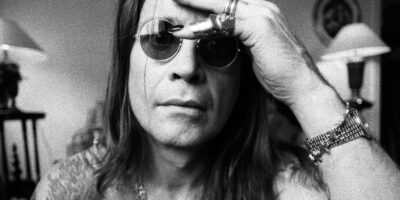

black midi emerged fully formed out of the absurdist nightmare of the post-Brexit UK, a group handed stacks of critical plaudits before even putting out a note of recorded music. While initially lumped in with their many, many, many less prolific contemporaries in a broad attempt to label a scene of young disillusioned prodigies emerging from the same grand cultural rot that allows a childrens’ book author to spearhead public campaigns for mass genocide, black midi managed to quickly distinguish themselves from their peers by simply being much better, and, simply speaking, much stranger. Eschewing their initial Battles-like, loop-obsessed blend of math and noise rock that could more easily be lumped in with the post-punk sludge of “post-Brexit-core” (I don’t like the term and the band certainly doesn’t either, but we’re settling with it for now), their last LP, CAVALCADE found the band’s current mode of proggy theatrics, a style which they’ve refined for their latest, HELLFIRE.

The text has coiled ever tighter around the context of the music it’s lumped in with, thanks to musical arrangements that feel more like stories unto themselves than ever. As with their last endeavor, HELLFIRE is incredibly cinematic, embracing the high camp of prog rock full throttle as a means of heightening the stories black midi are trying to tell, now delivered by first person perspective from a cadre of generally wretched characters. All of them feel like demented retreads of the kind of guys Robert Altman used to make films about, from Tristan Bongo, the military private so scarred by battlefield memories that he chooses to spend the rest of his life gambling on horses, to the unnamed adolescent assassin who publicly takes down a mediocre boxer on “Sugar/Tzu.” There’s much happening here, perhaps too much to take in in any one place, a sort of hyperextension of the “do everything but feel nothing” attitude that seems to come part in parcel with most of the current wave of British buzz bands.

This comes down to a callously nihilistic viewpoint from every song’s narrator, all of them showing a disregard for the lives of others as well as their own. This is not to say that black midi engages with this sort of spiteful thinking directly from their personal mindset, no. Rather, being in a generation that is as cynical of these types of people as their own makes the sheer idea of them seeing wildly negative consequences for their actions an incredibly funny idea to imagine. Take “Dangerous Liaisons,” a jazzily lilting tune that scans part old wive’s tale, part chick tract as it follows a man so gripped by temptation as to commit a hired hand murder for the devil. The song literally slams the eject button on itself with a spooky rattling exit as its narrator gets dragged to hell by Satan. More than anything, that’s just plainly funny to listen to them execute. It’s this brash humor tilted against bizarre and violent images that make up the bulk of HELLFIRE’s comically tilted darkness, jokes that only land harder the more you realize how plainly evil they are.

In particular, album closer “27 Questions” documents one Freddy Frost, a born entertainer who promises his audience a live presentation of his final will and testament, along with a grand screaming tribute to his life’s work. The song alternates between ominous delirium and an earnest joy in giving the man his final creative sendoff, a Joe Gideon-esque performative end. The song reaches for musical gestures so hacky that they feel genuinely unexpected as moves for the band to pull, grounding a Looney Tunes-like arrangement into something that could truly emulate the described spectacle. At the end of all of it, he enters a vicious death knell on stage and the audience’s only managed reaction is laughter at the old man’s troubles. What a hoot.

—

All things considered, the biggest stumbling point I’ve seen in others’ engagement with HELLFIRE has come down to asking the simple question: “Why make this?” Why make a record with such immediate hostility to the greater world, one in which so many are brought to ruin by their own choices? Why make a record so insistent on passionate exuberance in its instrumental palette contrasted with complete disdain for the subjects whom it chooses to portray? black midi are, in some manner, reflecting the world they find themselves in. In contrast to living through a mundane dystopia, they choose the vibrant excess of a world going down in flames, rife with melodrama, bitterly laced humor, and extravagant string sections. By their standards, an imagined devil could be a more entertaining tormentor than any of the real ones we’re forced to live with.

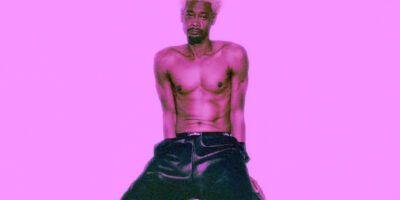

In sheer contrast to black midi’s more cartoonish bent, there’s Chat Pile’s debut LP, GOD’S COUNTRY. The band emerges from the heart of the American southwest, brandishing acerbic lyrical presence from performer Raygun Busch to present their take on uniquely American decline. Up to this point the band had proven themselves adept in their particular lane of post-Yow-ian noise rock sludge, leapfrogging from their two stellar EP releases in 2019 to a signing with stalwart San Francisco experimental label The Flenser. So comes this record, which builds upon everything the EPs had to offer, but with a more unflinching look into the dread they’ve already built themselves around.

Chat Pile’s work has always portrayed a distinctly American sense of flailing, people pulled down into the meat grinder by things beyond their own control. It is this American late-capitalist cruelty that gives their work its rancid sense of realism, even if it approaches absurdism by bellowing “send my body to Arby’s!” in the same breath it documents the overbearing evil of state-sanctioned abuse within American policing. It’s simply all too much at once, as is the point.

GOD’S COUNTRY hits harder for me than any other record of this particular style or subject matter because it’s the first time that, despite the tendencies of extreme music to embellish itself with violent subject matter, the situations evoked on record feel realistic in their terror. There are dozens of bands who can and have written about many of the subjects discussed on this record with their own high standards of quality, but none have felt quite as capable of removing the divide of the fourth wall between themselves and the listener. Chat Pile have found a way to speak to my own fears of disembodiment, obscene violence, and greater worldly decline in a way that feels panicked and personal; I can stomach plenty of other hyper-violent, fatalistic items of media around me, but GOD’S COUNTRY gives me pause because it embodies the reality I’ve come to be afraid of.

—

There’s a term of online slang that’s passed around to describe people who engage with a particular mindset of internet-age nihilism, one forced to face the terms of late-capitalist meltdown: “doomer.” While I personally remain too much of an optimist to fully give into that kind of thinking, it’s easy for me to see the place it stems from, to see the machinations of the greater world unfolded and realize one’s own powerlessness in stopping the machine from moving on to be, as Chat Pile themselves have termed it, “the cattle shoot of global capitalism.”

Not many bands (especially in mainstream “rock” and “pop” conventions) have tried to engage with this level of specific and intentional discomfort because, simply speaking, there’s no means or market for them to. Even looking at black midi, a band who previously wrote very directly about current savageries like the lead-based poisoning of Flint, Michigan’s water supply, the songwriting topics were mostly approached with a flowery language and instrumental flourish that could allow for space to disengage. On HELLFIRE, it’s enough thematically to be disembodied and given the space to merely laugh or nod along. But the moment we’re placed directly and unsympathetically inside the inhumanities and horrors of a song like “grimace_smoking_weed.jpg” (yes, that is the title…), the cushioning between art and those who engage with it crumbles down—you can’t engage with it as an escape when distress is being shoved directly in your face. There lies the inherent alienation between artist and audience that feels impossible to get around.

Similarly, I cannot in any good conscience say that most people will enjoy listening to GOD’S COUNTRY, but it is an album that, if nothing else, feels deeply necessary. The existence of a record that recognizes that humans generally do not fuck around and avoid subjects when they are the source of our own direct endangerment and shock is a surprise to see if only because it lands its punches so perfectly. It’s my favorite record I’ve heard this year and I loathe my choice to return to it again and again.

Anyone can write something like GOD’S COUNTRY to a vague degree, but Chat Pile remain one of the only groups who can inject the animalistic distress into the heart of the music with such intense hyperreality—it’s not enough to have a song in which its narrator plans to commit suicide, but to do so while apologetically asking for some privacy in it, bellowing out the name of a popular fast food mascot as an aura of hallucinatory loathing? This is the feeling we keep trying to avoid. And if we feel that the outcome approaching us is inevitable, what good is consuming art that avoids it? There’s few artists willing to grapple with the void, but at least it seems a few are willing to stare at it long enough to reflect something back.

Comments