In 2009 Steven Porfiri was accused of never having played a video game before by someone on a GameFAQs message board, and the insult has haunted him ever since. Now, as the Senior Games Writer for Merry-Go-Round Magazine, he’s finally been given a platform to prove that not only has he been playing video games, he writes about them as well. I Played a Game Once is an inside look into what he is playing, and how it has any bearing whatsoever on our current moment. It’s basically like Carrie Bradshaw’s column but with more discussions about save-scumming.

One of the most fun things you can do with a game is try to break it. Pretty much every player does this in one way or another: You can either go along with what the game has in store or you can break off and see what you can do to forge your own path. Some games will allow you to do this, and some, like THE STANLEY PARABLE, make it the running theme of the game, but other games don’t exactly have that scope, so you literally find the border of the game’s world. You hit the “invisible wall,” determined by a literal invisible wall or some other sort of in-game threat to get back on track. A game will only let the player explore what the narrative has planned for; some games will account for this, like THE STANLEY PARABLE, and others, like ADIOS, bring players along for the ride.

When I first heard of ADIOS it was pitched as a narrative-focused indie game with a relatively small team and pretty narrow scope. As someone who had just thrown themselves neck-deep into expansive fantasy MMOs looking to find meaning in the experience of human interaction, I was looking for, well, the opposite of that, I guess. I wanted to see what Mischief had to offer, and noting the buzz around the game’s release, I figured it might be fertile ground for exploration.

I knew I was gonna make this joke the moment I got to this point in the game

Ostensibly, ADIOS is the story of a pig farmer who disposes of bodies for the mob while deciding that he no longer wants to dispose of bodies for the mob. The game takes place over the course of a day as the hitman, who usually brings the bodies, tries to talk him out of his decision, while both knowing that no one simply cuts ties with the mob.

There’s a post in the Steam Community section for ADIOS where a skeptical user asks, “Is this one of those games that you play for two hours and everyone calls it art?” ADIOS has the feeling of a short film, one might call it a character study or a meditation piece. There are five speaking characters in total and while there are various activities or chores to do, there is only one real level to explore. It’s a simple game, but it emotionally manages to cover quite a bit of territory.

With a small toolbelt ADIOS begins to unravel the personalities of every character involved, centrally asking why a pig farmer would make a deal with the devil as he did, and what would possess him to end his somewhat-Faustian bargain prematurely. What it turns into is an exploration of regret and the search for atonement as we watch the farmer go about what is perhaps his final day with his business partner, potential killer, and the closest thing to a friend he seems to have. We watch as he deals with his decision, occasionally wavering as the weight of his choice washes over him from time to time, but never going back on his decision. As his end nears we watch as he essentially composes his own will, trying to make arrangements for things to be passed on, things to be taken care of, and animals to be set free. He knows what has to be done, and if it’s gotta be done, there are other things that need to be done first.

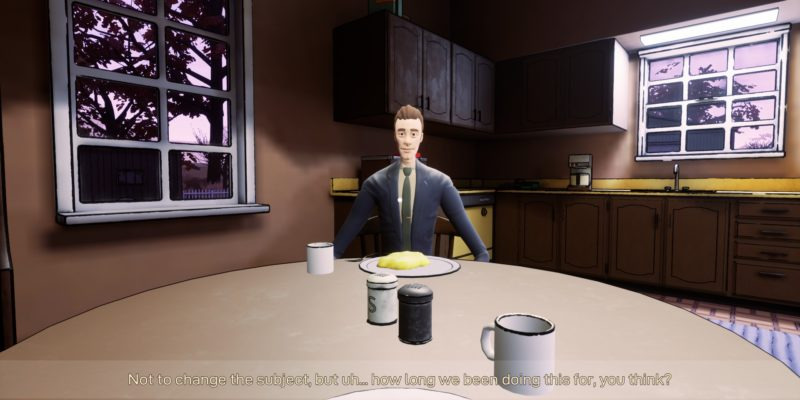

Like breakfast, for one thing

I say “we watch” because the game is largely on rails. Part of its similarity to a film is that there’s not much for the player to really do in terms of leading the character around. There are some moments that translate to the medium of gaming, such as trying to fish for the giant catfish that lives in the pond behind the farm, and certain dialogue options can lead to slightly different outcomes, but it all ends the same. The farmer has made a series of choices, and you, as the player, have to bear witness to their consequences.

But with a consequence as dire as getting whacked, we go back to the idea of “breaking” games in order to explore different outcomes. The first time playing ADIOS was somber and arresting, with an unexpectedly visceral ending that made me have to sit with myself for a bit. But going back a second time I wanted to see if the game would account for my own attempts to defy fate, or if it presented an option for an alternate ending. I’d noticed that during some of the more emotionally intense sections of the game there were options for dialogue that were grayed out, and couldn’t be used even if they were selected. Perhaps there was a new game+ situation, in which I could beg for my life or unload all the secrets I’d been hiding from my family in order to justify my actions?

Well, there’s always… but I’m getting ahead of myself

Alas, there was no such option. It’s up for debate whether the dialogue options exist as part of the game that hasn’t been fully built yet, or whether they’re there to demonstrate the turmoil of our main character’s mind and his inability to say what he wants. For what the game left me with, I think the second possibility is more affecting. The dialogue options involve giving in to farmer’s fear, his shame, and other unhealthy interpersonal options. But the inability to select them feels like a reinforcement of his character; a haunted man desperately trying to atone for his transgressions the only way he knows how, even if it means his end.

There are acknowledgements of the gaming instinct to outwit the game. The farm is full of the sort of refuse a farmer might accumulate over the year, and during the free-play section of the game you can explore as much as you’d like. The various shacks and sheds that litter the grounds, rusted out semis, the remnants of a fire pit, even the farmer’s photo-processing room in his home, all facets that flesh out the character’s past. In my attempts to flee fate, I even stumbled upon a storm shelter, or perhaps a bomb shelter leftover from the panic of the Cold War. Why wouldn’t the farmer simply hide out in here, I wondered? Turns out that this is a potential aspect of the story, provided the game sells enough copies to pay for its implementation.

What horrifying CLOVERFIELD LANE secrets do you hold?

There’s a sequence in the game where you and the hitman go skeet shooting together. You talk about guns, briefly, but soon the hitman explodes at you, furious about your stubborn attitude regarding ending your business arrangement. Before that, a very basic equation presents itself as the farmer cradles a shotgun while the hitman isn’t looking. If you remove the hitman, you remove the danger. Sure there’s someone else in the car, but you could probably take care of him too if you were careful. My first playthrough I definitely considered it, but I ultimately allowed the conversation to play out. The second time through, while he wasn’t looking, I squared the aiming reticle on my longtime associate’s head, looked down the sights, and blasted him with my shotgun.

The only reward I got for solving the equation was an achievement simply titled “Nice Try.”

Can’t blame a guy for trying.

Ah! Nevertheless

As games are increasingly updated and upgraded post-purchase, it’s possible that their meanings and overall impacts can shift and change the more things shift. This was once a conundrum purely situated in the realm of gaming, but the transition to online streaming services makes this aspect of artistic transformation an issue for film critics as well. It seems like if Mischief can sell more copies, they will, in turn, add more dialogue options as well as more avenues for different endings. It remains to be seen what choices will be implemented and how they’ll impact the current narrative.

As ADIOS currently stands, it’s a meditation on the immutability of one man’s choice, and what about him causes him to commit so heavily to it. Even as the player attempts to outrun fate, attempts to defy the stars like Romeo Montague with a gamepad, the character remains steadfast in his earnestness to atone no matter the cost. ADIOS granted a look into the turmoil of a condemned man’s mind and asked if you knew what the right thing to do was, would you do it even if it meant a great personal cost? And for me the answer was no. I’d try to run away.

Comments