This article previously appeared on Crossfader

Contributors Ian Campbell and Kevin Cookman stayed until the bitter end of Sundance 2018. Read their thoughts on the second half of the festival below and catch up with their thoughts on the first half here.

AMERICAN ANIMALS

Director: Bart Layton

Genre: Dramedy

Maybe AMERICAN ANIMALS, the narrative debut from Bart Layton, helmer of documentary favorite THE IMPOSTER, would feel fresher if it weren’t coming right off the heels of I, TONYA. A meta, docu-fiction depiction and dissection of a farcical, goofy, homegrown crime (in this case, the attempted 2004 Transylvania University heist of first edition texts worth millions by the hands of a ragtag group of students) and the interpersonal abuses that compound for severe shifts in tone and subject matter, there hasn’t been a more immediate “I liked [x], can you recommend another movie just like it?” film than AMERICAN ANIMALS. If you ever wanted to see a filmmaker desperately try to prove himself, Layton’s stylistic overcompensation should be in the stack. Admittedly, several of his tactics are quite effective. A conversation based on the passing of a blunt, each pass transitioning to a different location, is almost as good as when actors’ voices crossfade into the voices of the documentary subjects.

As a film about dueling perspectives, Layton finds really clever and enthralling ways to portray a web of lies and poor memory; I just wish he didn’t abandon this thesis once the heist takes over. What should be the film’s mantlepiece becomes a tar pit for pacing. The self-aware elements take a backseat for a strained, overly-dour temper, and the once exciting and eclectic cast of characters (Barry Keoghan and Jared Abrahamson shine bright, while Evan Peters does his usual overacting shtick) become insufferable cry-babies. Layton’s electric debut was meant to take the town by storm, but, in the end, it was really meant for the $7 Target rack: decent, but fleeting. [Kevin Cookman]

ASSASSINATION NATION

Director: Sam Levinson

Genre: Comedy

ASSASSINATION NATION gives a first impression that purposefully sets the entire film up for a redemption. Opening with a trigger warning highlight reel of the movie you’re about to see, with each warning stamped bold across the entire screen, it’s a move so assuredly obnoxious that it will certainly dissuade many from continuing. It’s a youthful blast of stylistic ego right from the get-go, and, honestly? It works so well. 18-year-olds convince themselves they own the world, so clearly, they own the film, the entire story of privacy-invading tech and mass hackings spawning a vicious witch hunt in the town of Salem, USA, right down to the music cues. ASSASSINATION NATION is what happens when Twitter eggs and Curious Cat death threats manifest as PURGE-like goons and murder the “sluts” and “whores” of Instagram. While not as maximalist as Joseph Kahn’s DETENTION, a clear inspiration, Levinson’s assaultive vision depicts America through the sensationalist lens of unconsciously consumed mass media: every interaction stamped with emojis, suddenly stock phrases stolen from black personalities, and the unnerving intensity of living in a day-to-day where world leaders threaten to nuke the planet over dick length.

The sole major acquisition of the festival, by surprise major buyer Neon (Tim League is coming for the industry with a vengeance), ASSASSINATION NATION is destined to be a benchmark of cultural discourse for many years to come: so urgently of the time, but also an incredibly valuable time capsule of a national attitude. It is to millennial feminism and internet culture as GET OUT is to race relations, ending as a fiery, gun-toting treatise on mass misogyny. While I’d feel comfier with the movie and its messages if it was written/directed by a woman, I can’t deny that Levinson very well understands the social tenor and its nuances. Equal parts grim and raucous, challenging and hit-you-on-the-head blunt, carefree fun and hopelessly dour, do feel free to call ASSASSINATION NATION tonally confused. I’ll call it one of the most exciting films of the year, instead. [Kevin Cookman]

BISBEE ’17

Director: Robert Greene

Genre: Non-Fiction

Robert Greene (KATE PLAYS CHRISTINE) is almost too good at taking what should be B-plots of a traditional documentary and turning them into the driving force of his non-fiction films. A traditional doc might feature the reenactment of a small but specific instance of fascism in Arizona as one example of larger problems in America’s treatment of immigrants or the general spectrum of labor movements throughout history. In Greene’s new film BISBEE ‘17, the centennial of the Bisbee Deportation (a mining labor strike broken by rounding up and shipping the striking workers to die in New Mexico) is the story, a lens to view history and the tensions between capitalism, race, and class that are all too relevant today.

Greene follows actors from a variety of backgrounds along with the organizers of this centennial “celebration,” charting their preparations and motivations for repeating an event that is by all definition a stain on Arizona’s history. Interspersed between interviews, radio show recordings, and audiobooks, filmed versions of the events leading up to the reenactment set the tone, creating the atmosphere of a ghost story echoing from the past to the present. Greene’s interest in performing is a perfect vehicle for making audiences empathize with the labor movement in the film. As the actors in modern day Bisbee realize the importance of the union protecting the miners and the more insidious racial motivations of the mining company’s owners, so does the audience. Acting is the easiest way for a film to inspire empathy, and by focusing his films on the process, Greene finds a backdoor into audience’s minds, intellectually engaging them with metatextual non-fiction elements and emotionally directing them to care about the issues he clearly seems passionate about.

It’s worth mentioning that BISBEE ‘17 is another explicitly pro-labor, socialist-leaning film among what seems to be a growing number at the festival, firmly on the side of labor unions and equal power between employer and employee. For as even-keeled as both “sides” are presented in BISBEE ‘17 (several people followed in the film are former employees of the mining companies), Greene doesn’t have to do much to ridicule the Bisbee residents who favored the deportation. They do it all their own, in their performances, in the reenactment, and in their interactions with the other actors. But his editing (Greene works professionally as an editor when not directing) gradually builds, adding information and surprisingly emotive performances, until the Bisbee Deportation feels not just misguided, but evil. It’s powerful and even though it could be written off as an American imitation of THE ACT OF KILLING, BISBEE ‘17 stands on its own as a unique film, further proof of the power of Greene’s style of filmmaking. [Ian Campbell]

BLAZE

Director: Ethan Hawke

Genre: Drama

The lumbering, kindly giant whose slurring stems from a mix of Pabst Blue Ribbon and natural drawl; Blaze Foley is *the* unsung singer-songwriter of outlaw country, getting his proper due by devoted fan and first-time director, Ethan Hawke. Written by Hawke and Sybil Rosen, Foley’s most doting and supportive partner, portrayed by the always spectacular Alia Shawkat, BLAZE is so much more caring and considered than the usual “bet ya didn’t know about this fella!” biopic. Described by Hawke as an indie country western opera, the film’s several framing devices keep music at the forefront, often having performed songs trigger flashbacks that flesh out the big fella playing in the back of the empty bar. Sweet melancholy as thick as molasses, warm as whiskey. Ben Dickey, while bearing little resemblance to Foley and looking something like a backwoods Post Malone, embodies his spirit so purely and tactfully. A portly, heavy-footed teddy bear with a wrecked liver, Dickey vividly conjures a man who lived through four lives’ worth of experience and selfish self-romanticization in his brief time on Earth.

Hawke so clearly has taken copious notes on the many sets he’s been a part of. This is the work of a learned, observant filmmaker, his approach to the story not unlike Linklater (who appears in a terrific supporting role), but not a carbon copy either. There’s a clear roadmap, but the folds in the pages are weathering, the paper crumpled. BLAZE’s study of Foley is quite astute, directly addressing the exploitation of his persona to be a self-gratifying, mythical persona in a film that so easily could have fallen into that trap (the single hokey failing is Hawke casting himself in a cheesy off-screen role). Blaze was not for you to know—he was a (literal) pillar to his extremely close and limited base. You can create work so genuine and homegrown, but ultimately, the corny bullshit prevails—guess all you have to do is keep playing, keep loving, and keep on drinking. So good that I sat and enjoyed watching a country western music biopic for 127 minutes. [Kevin Cookman]

THE CLEANERS

Director(s): Moritz Riesewieck and Hans Block

Genre: Documentary

The internet is a dangerous place, for its status as the last bastion of free expression (not really true anymore), a playground for anonymous abuse, and role as a magnifier of the human id. THE CLEANERS, a new documentary directed by Moritz Riesewieck and Hans Block, concerns itself with the people tasked with making it a “better place,” the content moderators hired (through a third party) by Facebook, Twitter, and Google to remove inappropriate, illegal, and dangerous content from their platforms to make the Internet “healthier.”

Through interviews and anonymous chat conversations with working content moderators it becomes clear that like much of the internet, what’s good or bad isn’t so cut and dry, especially for a majority of the moderators featured in the doc. It’s not formally daring, but is impressive as a debut stab at the medium, well-composed and edited, if plain. The subjects of THE CLEANERS are outsourced labor, living and working remotely in the Philippines. A large portion of the doc is spent establishing how important context is to content moderation, how potentially dangerous content can slip through the cracks, and how much of a burden the graphic imagery can be to the moderators themselves. It’s eye opening and particularly relevant as internet literacy has become more important than ever, but as a story it doesn’t really resolve.

THE CLEANERS does an excellent job establishing the problems that exist on all these online platforms and how the current solutions are mostly inadequate to counteract the various bad actors online. What it doesn’t do is offer any solutions or resolution to it’s story. It doesn’t have to solve the problem, but it would’ve been valuable to at least explore some options rather than attempt to drown the audience in worse and worse examples of internet run amuck. In the end THE CLEANERS takes an interesting topic, adequately shows how dire it is, and then ends. It’s powerful, perhaps even a call to action, but it leaves you wanting more. [Ian Campbell]

DON’T WORRY, HE WON’T GET FAR ON FOOT

Director: Gus Van Sant

Genre: Biopic

Gus Van Sant, a longtime force in both arthouse and multiplex spectrums, rebounds from the disastrous SEA OF TREES (for real, keep all Americans out of Aokigahara) with a biopic on John Callahan, acclaimed, Portland-based paraplegic cartoonist, starring Joaquin Phoenix in an old-fashioned prestige role. I’ve concocted a new diagnosis for a certain category of film: it’s called MILK-ing. Remember 2008’s MILK, the Sean Penn-led Harvey Milk biopic? Remember those incredible trailers, so moving, vibrant, and rhythmic? Filled with life and immediacy and how it ultimately advertised a movie running on a quarter tank of all those things? Ladies and gentlemen, I got MILK’d. The primary issue that plagues DON’T WORRY is crystal-clear in any scene involving Callahan’s sobriety group, his alcoholism and adherence to the 12-step program serving as the film’s crux. Each recited story feels like a grad school audition, exhausting attempts at naturalism that falter because it’s clear that delivering what was written on the page is of utmost consequence. The actors are playing off of the writing, not each other or themselves. Van Sant fails to capture any of the rawness or vulnerability of these group talks and, in extension, of Callahan’s entire life.

I am an eternal slave to the screen talents of Joaquin Phoenix, one of the best to ever do it, but it is disappointing that a once daring creative maverick like Van Sant has completely lost his edge; a braver, more self-aware filmmaker would have let a unknown, disable talent carry his own amongst an all-star cast, studded with Rooney Mara (a complete misfire of character and performance), Jack Black (an under-utilized highlight), and a slew of esteemed character actors. Jonah Hill’s much-buzzed performance, though admittedly charming, is played at a register designed specifically for the Best Supporting Actor nomination reel. In a widespread push for mass representation, it’s a shame that stories such as Callahan’s don’t facilitate exposure for unique talent. DON’T WORRY, HE WON’T GET FAR ON FOOT is a missed opportunity, and not just at a casting level. [Kevin Cookman]

HEREDITARY

Director: Ari Aster

Genre: Horror

Often times the scariest idea is that fate is predetermined. Life has a plan for us and the longer we live, the more the gift of life feels like a curse: out of our control and cruelly constructed. In Ari Aster’s new film HEREDITARY (already A24’s big ticket item this summer), this fear of fatalism is the character’s reality. HEREDITARY covers the tumultuous disintegration the Graham family goes through after the death of their reclusive grandmother. Matriarch Annie (Toni Collette) spirals into guilt and paranoia, blaming herself and others for a series of circumstances that grow worse by the day as her family’s “grief” transforms into something a lot more like a haunting. Stripped down to its most simple device, HEREDITARY is a variety of different plays on tension. Tension is one of the most essential horror film tools and HEREDITARY wields it excellently, weaponizing a horror element that often gets overlooked in favor of shock and cheap thrills.

This starts with the score, which is both oppressive and unnatural, elevating seemingly innocuous scenes like the film’s funeral opening into a waiting game of slow-growing dread. In combination with the score (and disarmingly crisp sound design), tension is ratcheted up further simply by withholding information from the audience as long as possible. Long takes of character’s face dramatically transitioning into looks of horror as the audience wonders would could actually be so awful are the bread and butter of HEREDITARY, a trick that would get repetitive if it didn’t work so well every time. This waiting is further punctuated by sound: motifs in the score and a particularly recognizable vocal tic (to say more ruins some of the surprise) that becomes a calling card of the film’s inevitable horror. This is the basic formula, with more traditional scares scattered throughout. The relentlessness of it generates a pervasive feeling of awfulness (all the better to make normal scares that much more powerful) that’s mirrored in the film’s narrative and the character’s experience.

When you experience something terrible, you expect more terrible things to follow. It’s a simple animal instinct, our basic desire to find and anticipate patterns taking control. In the same way, when a movie scares you, you expect it to scare you again and scare you worse. For the characters in the film, Annie and her family, the anticipation of bad luck turning worse only serves to heighten their pain and make each new twist of the knife that much more unbearable. It’s part of the elegance of HEREDITARY; it never pretends like things won’t get worse and when it works, it constantly one-ups itself with how bad it can really be. This is only reinforced by the supernatural elements of the plot, notions of inherited trauma, “deals” left unsatisfied, and curses looping through the character’s individual plots, damning them for something almost entirely out of their control. The power of horror films is their ability to make audience’s forget or at least allow themselves to ignore the basic tenet that nothing they see on screen is real. This film is particularly suited to get audiences to that point, almost bred to be as efficient as possible at it. In HEREDITARY bad endings are just that, inevitable and seemingly genetic, for both the characters and the audience. [Ian Campbell]

LIZZIE

Director: Craig William Macneill

Genre: Period Drama

Blech. Craig William Macneill’s FOXCATCHER-esque, cold-as-ice illustration of the infamous Lizzie Borden murders is lavishly empty. The primary draw is the central romance between Chloë Sevigny and Kristen Stewart, the contemporary and modern queens of indie acting, respectively, so to see them have nearly zero chemistry is sinking. There’s no spark, no danger, just French kissing and heavy petting. Not even Lizzie’s stern, overbearing father is portrayed effectively, with Jamey Sheridan sounding more like a kindergarten teacher than an emotionally abusive monster worthy of a hatchet to the face. I’ll give Macneill this: the goopy, gruesome murders are fueled by some accelerative, midnight movie-friendly bloodlust.

LIZZIE is a story of passion executed with salacious lust and nothing more. The rudimentary nonlinearity of events, the film starting with the murders then awkwardly flashing back to the aftermath and then the events at seemingly random points during the film, this pastiche approach to revealing the truth in bits and pieces is a last-ditch attempt to invigorate the structure, but it only drags the movie out to a further interminable length. While I agree that inside every man exists a patriarchal evil, the film’s depiction of toxic masculinity is cartoonish. And the cinematography is so basic, depending mostly on distance to communicate the emotional isolation . . . Yawn. So many other movies, some at this very festival, so deftly communicate their protagonists’ interiors through inventive film form; there’s no excuse for the laziness of LIZZIE’s staidness besides ineptitude. [Kevin Cookman]

MADELINE’S MADELINE

Director: Josephine Decker

Genre: Drama

Whoa.

Josephine Decker’s MADELINE’S MADELINE. On one level, it’s ACTOR-DIRECTOR WORKSHOP: THE MOVIE, but on another, it’s an immersive portrayal of mental illness and the artistic process, an experience as close to stepping into a person’s head as the worming through the crawlspace in BEING JOHN MALKOVICH. A feverish blur of female adolescence, MADELINE’S MADELINE is largely beyond my comprehension. It is a film on a completely new visionary wavelength, with scenes fading into each other as lucidly as our thoughts, an already intimidating world seeming so much more dangerous and unpredictable. It follows 15-year-old Madeline, played ferociously by a Freddie Quell-tier Helena Howard, a budding actress who finds solace from her frenzied mental illness in experimental theater. Her director, a warm, yet sinisterly intentioned mother-to-be (Molly Parker), is fascinated with how she views the world, leading the troupe’s play to be about Madeline’s affliction. Every moment of Madeline’s life exists in this dispiriting daze of not having anyone understand your condition, especially not your closest loved ones.

MADELINE’S MADELINE condemns the exploitation of the delusions and pains elicited from mental illness for the sake of art. Decker adroitly walks the line of scrutinizing these directorial methods, while making a film that revels in the process. The “awaken your inner-self” drama teachers break down when the performance of the actualization of peeling your layers is bypassed and true confrontation is incited. There’s spontaneity, but there’s a script. Who are we if not the perceived projections of others? Musing on identity like Oshima’s finest, Decker both gently and aggressively frames Madeline as she fights off the pressures of imparted identity, coming to terms with both Madelines: Madeline and Madeline’s Madeline. It is the story of a young woman taking literal direction of her own narrative. Boldly conceived and bravely executed, MADELINE’S MADELINE doesn’t feel constructed through the traditional filmmaking process—it has miraculously poofed into existence. [Kevin Cookman]

NIGHT COMES ON

Director: Jordana Spiro

Genre: Drama

Longtime TV actress Jordana Spiro, the white-as-bread lead of TBS’s MY BOYS, makes her directorial debut with . . . a socially conscious, ground-level exposé of black foster children in Philly and their search for purpose beyond lifelong definition as breathing government files? Okay. Unexpected, to say the least. Following the immediate events of her release from juvenile detention, Angel LaMere reconvenes with her little sister to embark on a beach trip that may or may not be an assassination mission targeting their father, an abuser who took their mother’s life. Every step of the sisters’ journey is maligned by restrictions, ranging from curfews and specific chaperones to being in constant contact with parole officers and abiding to remain within certain city radiuses. Big Brother is now; in fact, it has been for people of color for centuries, the data-management has just gotten more efficient. Spiro, regardless of her ethnic background, conveys a palpable portrait of living in bureaucratic shackles. Several asides hit home: when Angel’s little sister brings her through her foster home, Angel peers into a child’s bedroom filled with toys and colorful walls. “Is that her real daughter’s room?” she asks. They pass by and enter one of several bare rooms with bunk beds and strewn clothes, holding pens for the homeowners’ good virtue trophies. Less powerful is the hackneyed excursion to a beachside mansion, a moment meant for the characters to interact with normalized wealth that feels like leftovers from better movies released just a few months ago.

NIGHT COMES ON is matter-of-fact, opting for moment-to-moment over artificial storytelling techniques. Beginning with a narration that is part spoken word, part exposition, the film doesn’t pick up any sort of dreamy essence until the very end, a creative choice that doesn’t entirely pay off given how much of a non-impression everything in between gives. Dominique Fishback, spearheading nearly every scene and moment of the film, is one-note, so dramatically overshadowed by her co-star, Tatum Marilyn Hall, a phenomenal young talent whose face is filled with a decade’s worth of experience and sorrow. If the world was a just place, Hall would break out as a superstar. A formidable, well-intentioned, promising, yet ultimately forgettable first feature. [Kevin Cookman]

OF FATHERS AND SONS

Director: Talal Derki

Genre: Documentary

Director Talal Derki achieves a visceral, unprecedented access to a subject unlike many other documentaries ever made. To gain the trust of a radical Islamist family training for jihad, Derki wiped his social media presence and posed as a war videographer who was seeking to make a puff piece on the Taliban and the state of progress in Syria. What emerged is a humanist, heartbreaking examination of cyclical and masculine psychological destruction, of which social mores fathers pass on to their sons and how they choose to honor the lineage. I saw OF FATHERS AND SONS in a heated theater, but my hands remained ice cold—this film does a number on its viewer. Seeing the children in boot camp being trained not to flinch by laying on the floor and randomly having the ground next to their heads fired at with live ammunition doesn’t feel real, but there it is, the systemic breakdown of youth, of humanity, right before our very eyes.

The family at the center of the film is never treated as a group of specimens, but rather a loving unit who only want the best for one other. The completely objective POV grants the film a quality that nullifies the ethical quandaries of how Derki got there in the first place. The normalcy of violence is startling—local soldiers of differing missions and causes cross each other on dirt paths like fellow hikers do. The men march with rifles while the boys brawl with rocks and dirt, two generations in different arenas but existing in a similar headspace. OF FATHERS AND SONS explores a culture of violence that isn’t exclusive to the Taliban. The sanctity of human life is more a fighting ideal than an active concern, and it’s impossible to not see this radical family as dissimilar from Southern American extremist groups. Perhaps we qualify the “Middle East” as the “other” to shield the American public from our inherent likeness to these war-torn nations. Ah, but remember: best not to ask too many questions. A transformative film experience. [Kevin Cookman]

PUZZLE

Director: Marc Turtletaub

Genre: Drama

I don’t want to disparage older audiences (they make up a majority of ticket sales), but you can generally smell an old person movie from a mile away. They’ve got the light romance and the light comedy and a cute, if slightly off, concept. They’re sweet, while still being a little adventurous. They’re just generally approachable and easy to digest. Often totally fine. PUZZLE is an old person movie. Directed by Sundance veteran producer Marc Turtletaub, PUZZLE is about quiet, anxious Agnes (Kelly McDonald) finding her passion and her voice. Her passion just happens to be “competitive puzzling,” and her voice sends ripples through her family as she asserts her independence from her conservative and regressive husband and falls in love with a pro-puzzler/inventor (Irrfan Khan). They’re ridiculously charming together, witty and playful and all that. Performances that would be at home in any romantic comedy, but they are the good parts of a film that’s far less adventurous. What’s disappointing about PUZZLE is that it pitches a good concept but doesn’t attempt to bat it any further than necessary.

Gradually, Agnes’s passion for puzzles is revealed to be an expression of her desire to assert control over a universe that at the outset she doesn’t have much control over. Puzzles are, after all, a chaotic mess with a clear and precise solution. The various lines about “missing pieces” and finally feeling “complete” more or less write themselves. But the film never really dives into that surface-level theme, keeping any kind of character complexity limited to Agnes and Agnes alone. Similar problems appear with the tone of the film, which modulates uneasily between whimsical comedy and traditional drama. What would fit PUZZLE the best would be emulating AMELIE, light whimsy grounded in a moderately unforgiving reality; basically, a fairy tale that takes place in the real world. But PUZZLE never quite gets there. Lines meant to be dramatic read as humorous and humorous elements often get passed over as the plot develops. For as fantastical as the concept could be (have you heard of competitive jigsaw puzzle solving?), the world that’s presented feels uninterested in fantasy and only slightly more concerned with vague Americana. It’s sort of a bummer and it leaves a nice film just a few steps below what could be a great one. But hey, your grandma WILL LOVE IT. [Ian Campbell]

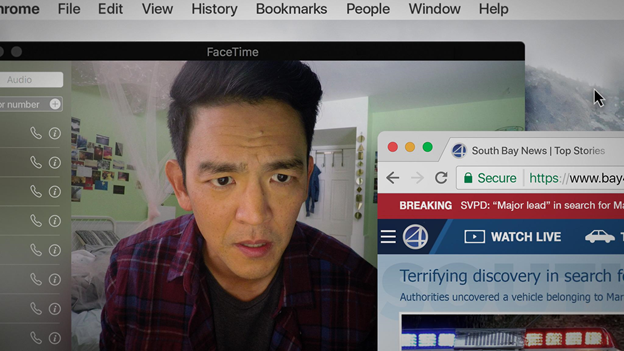

SEARCH

Director: Aneesh Chaganty

Genre: Mystery, Thriller, “Screen” Movie

SEARCH has legitimized the screen/desktop movie genre. Well, maybe it hasn’t yet (we don’t have good terminology for these kinds of films!), but it gets the closest, closer than any previous films (here’s to you, UNFRIENDED). As a thriller, playing out a mostly well-paced mystery that’s narrative wheels fall off at the end, SEARCH would be satisfying. However, if you take into account that everything on the screen is animated by hand and not screen captured, SEARCH more than earns the awards it won at the festival.

SEARCH is the story of David Kim (John Cho, solid as always) trying to find his missing daughter with the help of the police, his daughter’s friends, and a whole lot of computer work. SEARCH does a good job going beyond the frantic typing and mouse movements to convey character, utilizing frequent video chats and actual camera movements (zooming in on specific elements of applications) to create some dynamism and fill in the Kim family beyond what we’re shown on the screen. The mystery is satisfying as well, revealing elements of David’s daughter he wasn’t aware of and ways of using her computer he couldn’t really imagine. It’s the kind of mystery, set in a familiar place, that feels solvable: the clues are there and you never get quite ahead of the characters. It keeps its pace until it decides twist and melodrama are more important.

Debra Messing plays Rosemary Vick, the detective assigned to the Kim case and the character saddled with the most exposition and clunky lines. Messing has experience with police procedurals, but her performance here feels weirdly out of step with Cho’s more grounded work. And as the melodrama mounts, the twists grow out of the plot, busting up the third act and preventing the most satisfying (and realistic) version of the film’s ending. SEARCH is formal success and entertaining as a tense and twisty thriller, but with some polish? This could be a perfect morsel. On some level it’s disappointing that the two biggest commercial examples of a screen/desktop movie are heavy genre films meant to be entertaining above everything. There’s a huge opportunity for something quieter and more thoughtful to really blow up this genre. Something deep inside of me wishes SEARCH was crossed with COLUMBUS and Kogonada had turned his careful eye to digital architecture instead of IRL buildings. A visually delicate exploration of a digital space is the next frontier. Still, this is the kind of experimentation that is thrilling to see at Sundance. Director Aneesh Chaganty has earned his accolades and added one more win to this burgeoning genre. [Ian Campbell]

SHIRKERS

Director: Sandi Tan

Genre: Documentary

As if in the Tim Schafer world of Psychonauts, Singaporean filmmaker Sandi Tan opens a small doorway into her brain and allows us to walk right in with SHIRKERS, a documentary that is part tone poem confessional, part mysterious scandal, part high school reunion, part career retrospective, and part seance of Sandi Tan’s passion project, a 1992 indie also named SHIRKERS. It takes less than 10 minutes for Tan to bring her audience to a wide smile and keeps it glued for the remaining runtime—a joyous celebration of collaboration as seen through digital video memories, rewound footage, and photo collages fluttering by like lyrical daydreams. It goes from vibrant expressionistic profile to an enthralling story of deceit and creative ruination, told in a way akin to sharing a flight of beers with Tan herself. Her curious eye, from 1992 to present, is ever functioning, inspecting personal memory as a film scholar would Marxist theory.

In detailing the bizarre production of SHIRKERS and how the director made off with the movie, Sandi interviews her best friends, all of whom were key creatives on the movie decades prior. In these moments, we abruptly step out of Tan’s head and see how her closest cronies see her. Jazmine Ng, a wonderful director herself, is brutally honest, her confrontational outbursts that challenge Sandi’s ego the source of huge laughs and pin-drop silences. “I know I’ll never get all my friends in the same place ever again. But here they are. With me,” Sandi narrates. Film is a time capsule, not just as historical records for the eras in which they are produced, but of our own cultural understandings and personal lives. Either in construction or viewing, cinema is synonymous with community. The sound of SHIRKERS (1992) may be lost forever, but the footage has survived, allowing the movie to live on in this newly resurrected form. SHIRKERS is a knock-out. [Kevin Cookman]

SORRY TO BOTHER YOU

Director: Boots Riley

Genre: Comedy

Get ready to hear the name “Boots Riley,” because SORRY TO BOTHER YOU is the type of explosive, buoyant debut that rattles a generational mindset and establishes new (but clearly inspired from old) avenues of social satire. What’s miraculous is that Riley found a way to film this story with live actors; as admitted to the audience at Sundance’s annual “This Is Not a Panel,” his most-watched film is THE MUPPETS TAKE MANHATTAN, so clearly his first film is one that seems tailor-made for a screaming black Beaker and a cocaine-snorting, orgy-obsessed Sam the Eagle. An anti-capitalist, Adult Swim-indebted modern PUTNEY SWOPE, Boots Riley’s feature debut (holy smokes) works so well because it understands the severity of our social climate just as well as it does the wacko reality of its own quirky universe. Zeroing in on labor union unrest, the American public’s propensity for institutionalized slavery, and the rise of seemingly attainable democratic socialism, the characters of SORRY TO BOTHER YOU bumble about whilst navigating a thorny socioeconomic landscape where pointless memes become radical political symbols and making a buck upstages one’s integrity.

Working a telemarketer gig, the black protagonist, Cassius, is urged to use his “white voice.” What follows is an imperfect ADR dub of David Cross’s voice emerging from Cassius’s mouth, a running joke that only gets better as time goes on. That’s the world this movie chooses to live in. And oh what a world this becomes as time goes on: SORRY TO BOTHER YOU is at one moment an urban slacker comedy, then a workplace farce, then a monster movie, then EYES WIDE SHUT, then maybe a Christmas claymation special, plus about 40 other types of movies. This is scientifically designed to thrill and excite during every single scene, and it never ceases. At the forefront is Lakeith Stanfield, one of the great performers of our time, maneuvering Chaplin slapstick with the acidic verve of absurdist, yet grounded, Black Twitter comedy. The only thing missing is a supporting role for Zack Fox, who I much rather would have preferred to see than the 1.5 too many subplots Riley crams in. The new wave of black cinema inspired by the success of Donald Glover’s FX darling ATLANTA is THE wave. Certain to be one of 2018’s cultural highlights, SORRY TO BOTHER YOU is both comfort food and a kick in the head. Hysterical. [Kevin Cookman]

SUMMER OF ‘84

DIRECTOR: Francois Simard, Anouk Whissell, Yoann-Karl Whissell

Genre: Thriller

Sweet Jesus, did this get destroyed by fellow critics. I’m no fan of HOBO WITH A SHOTGUN’s four-year-late bowel movement, TURBO KID, either, but that team’s follow-up, SUMMER OF ‘84, is so clearly a step up. No longer looking like a 100-minute YouTube video, the production value and period setting of SUMMER OF ‘84 is admirable, its references to the culture no more tacky or forced than your neighborhood STRANGER THINGS. In fact, this packs in its homages a whole lot better than the massive Netflix series. The kids huddle Scooby-Doo style around an encyclopedia to research chemical compounds, porno magazines are traded, and department store walkie talkies offer constant communication for the friend group. Early mentions of The Cold War echo the seemingly never-ending paranoia of the decade, in addition to cleverly foreshadowing the weirdly dour ending. There’s an admirable tactility here, even though the greatest inaccuracy is so blinding: fat kids (and, look, as one, I can say this), at no point in the 20th century, would ever wear a baseball tee and *especially* not a white one.

Essentially FRIGHT NIGHT meets REAR WINDOW, but at the age-range of THE MONSTER SQUAD, SUMMER OF ‘84 is an R-rated version of those grade school books like “My English Teacher Is an Alien!” Following a group of kids who suspect their neighbor, the town-favorite police officer, is actually a child serial killer, SUMMER OF ‘84 puzzlingly has zero twists in store. Within the first six minutes of the movie, you know so very clearly that this cop is up to no good. And you beg the movie to do something different, that this is a major red herring for space aliens or a cult or, oh god, I’ll take even a zombie, I’m desperate. But nope—this type of simplistic mystery is well-worn YA novel territory. A decent yarn, but lacking any subversion. I can’t help but think about how dramatically better and fascinating this would be if the kids weren’t white. This fetishistic wave of ‘80s revivalism is a larger effort to recapture our fleeting youth, much like the kids of SUMMER OF ‘84 try to do whilst uncovering the neighborhood murder mystery; the group’s on-page chemistry is dynamite. Rather than being a group of child actors tossed together, they seem to be friends who genuinely care about one another. It’s refreshing. If only the kids could actually, uh, well, act better, and if only every woman in this movie wasn’t the worst written character in film this year. [Kevin Cookman]

TULLY

Director: Jason Reitman

Genre: Dramedy

The secret screening of Sundance 2018 was Diablo Cody and Jason Reitman’s third collaboration, TULLY, a film about the mediocrity of motherhood that may be their best shared effort to date. Marlo, played by the massively versatile Charlize Theron, is a downtrodden mother of three who is gifted a night nanny, a service worker who tends to a newborn at night so the parents can sleep in peace, by her successful brother, a nice bit part for Mark Duplass. Hesitant to accept out of spite for their differing financial standards, Marlo’s situation far more homely and frugal, she eventually does and finds that the nanny, Tully (a delightful Mackenzie Davis), is key to revitalizing the dull existence she carries on of no longer being her own person. Smart, mature, and contained, this is the type of psychological dramedy that would have thrived in the late ‘60s/early ‘70s. Films of this ilk simply do not get made anymore. A middle-class movie that functions not as an event picture nor as an internet skit, TULLY feels like it was plucked from a long-dead film market, here to remind us the value of the limited-scale, focused drama. Combining the crowd-pleasing, razor-wit of JUNO and the overbearing cynicism of YOUNG ADULT, TULLY begins as a sardonic vision of parentage that reveals itself to be a wiser, feeling impression of family and leadership. Reitman’s been in a bit of a rut, while Cody has been AWOL, so to have a film that pins the two as creative forces to reckon with once more is a splendid revitalization in and of itself. [Kevin Cookman]

TYREL

Director: Sebastian Silva

Genre: Comedy

Ah, Sebastian Silva, the undisputed king of intriguing, but always undercooked, indie movies. His latest, TYREL, hints at being his beefiest: the only black man at an all-white male mountain getaway birthday party. Tyler, played by Jason Mitchell, here in a string of recent performances designed to designate him as more than an Eazy-E impersonator, is greeted by the men, of which he’s met in passing and is accidentally called Tyrel by one. Moments later, at the birthday boy’s cabin (his grandparents’, really), he says that, “She likes everything white.” Moments later again, a game of impersonating accents turns into a minstrel show. Did I mention that the birthday boy is played by Caleb Landry Jones? It sets itself up to be tense, mumblecore, GET OUT-esque genre exploration of race relations and micro-aggressions, but it quickly becomes just a bad party simulator. You know that feeling when you’re at a function and know no one there, so you gravitate towards the dog and play with it the whole night and pretend you’re answering emails in order to avoid interaction? Well, that’s the entirety of TYREL, a movie that may be too subtle for its own good. There is a good chance that you and I have lived through this movie just last weekend, and with about the same level of mental clarity. So what is its worth? We often say that the best of cinema is a reflection of the self, but what happens when it’s literally a direct reflection? At least it’s funny; most amusing is how Tyler is uncomfortable with every guy at the cabin, but for some reason gravitates to Michael Cera, essentially playing the THIS IS THE END version of himself. TYREL is a fascinating anomaly, both one of the densest and wafer-light movies of Sundance. [Kevin Cookman]

WE THE ANIMALS

Director: Jeremiah Zagar

Genre: Drama

Based on Justin Torres’ novel of the same name, WE THE ANIMALS is the surprisingly sophisticated, seemingly seasoned narrative feature debut of Jeremiah Zagar. Possessing the grain and texture of a family home video, Zagar’s film follows a triad of Puerto Rican brothers as they navigate childhood in rural upstate New York and an abusive household. The three children roam their hood like a pack of cubs, roughhousing at every corner and making merry with the everyday jubilation of their surrounding environment. These three are never slowing down, finding joy and amusement in anything and everything—it’s quite inspiring. Focusing on the youngest of the three, WE THE ANIMALS could be qualified as a Puerto Rican MOONLIGHT, but to say so does a disservice to both films. Yes, WE THE ANIMALS is as if Chapter One of Blue’s story was extended into a feature, but ANIMALS’ commentary on fatherhood and the family dynamic drives the film more than the child’s personal development (a shift that works greatly in favor of what Zagar is looking to achieve). The result is a strong film, if an easily forgotten one. Much like NIGHT COMES ON, it’s a formidable piece of realistic fiction that, well, certainly exists, but it doesn’t quite thrive. Holding it back is its adherence to a series of awful animated sequences.

The mix of upbeat electro score over Sundance-friendly drawing montages that attempt to capture childish wonderment with ultra-realistic portrayals of neglect and poverty is a little queasy, a stylistically bogus and insincere depiction of the lead character’s despair. I’m not against the film granting him a respite from the oppressive life he leads, especially not through art, but the montages are so cheerful, yet we never see him smile until a climactic moment of maturation. These moments uplift the audience, but at the expense of forgetting what movie they’re in. [Kevin Cookman]

Comments