SPOILER ALERT: This article discusses narrative beats that occur several hours into the game

In a threadbare digital redoubt, you find refuge from discourse. Patience: low; expectations: none. Hands still shaking after what you saw those cops do. Dispassionately you realize this place was a review for a video game. In a moment you’ll toss the place for serotonin, not in a position to complain when you find its freebase form, ego-reinforcement, instead. But a letter at the atrium gives you pause. Held up to the light it says, “What would it mean if THE LAST OF US PART II was the last video game ever made?”

THE LAST OF US PART II is well-made. The action-horror splendor of infiltration/extermination/escape, which characterizes enemy encounters, and the requisite Naughty Dog pathfinding, are easily slid, one after the other, flowstatelike. The minute-by-minute and block-by-block way it unravels charges the player’s sense of a sweaty controller with roleplaying energies. These energies are sustained by highly-detailed character animations that have been lavished with that particular video game semblance of the humanizing thing which actors acting in a film can be said to give to time.

In the game’s kill/hide/craft flowstates, these animations proliferate faster and more seamlessly than I can obviously read the triggers from, so that they become a nearly-unconscious felt aspect of the environments I move through, and then as forgettable as Pac Man’s wakka-wakka mouth. After a certain point of controls-mastery, the animations became more satisfying to me as a well-executed button presses on my own part. In a similar way, roleplaying energies over the course of the game pale from Ellie’s fear into a disassociatably-vague tension.

For a good while, though, to maintain that feeling of desperation, escape, and redemptive vengeance, encounter design and skill progression are well-matched. From whatever distance you want to look at the gameplay, a so-very-measured dollop of fly-in-the-ointment player-antagonism keeps things dynamic. The players’ first encounter with the Seraphites, a highlight moment, opens with the disquieting lesson that holding R1 extracts arrows from your body. Switching characters mid-game was another bold trick, though those sections, nearly half of the game, never escape the feeling of being vestigial.

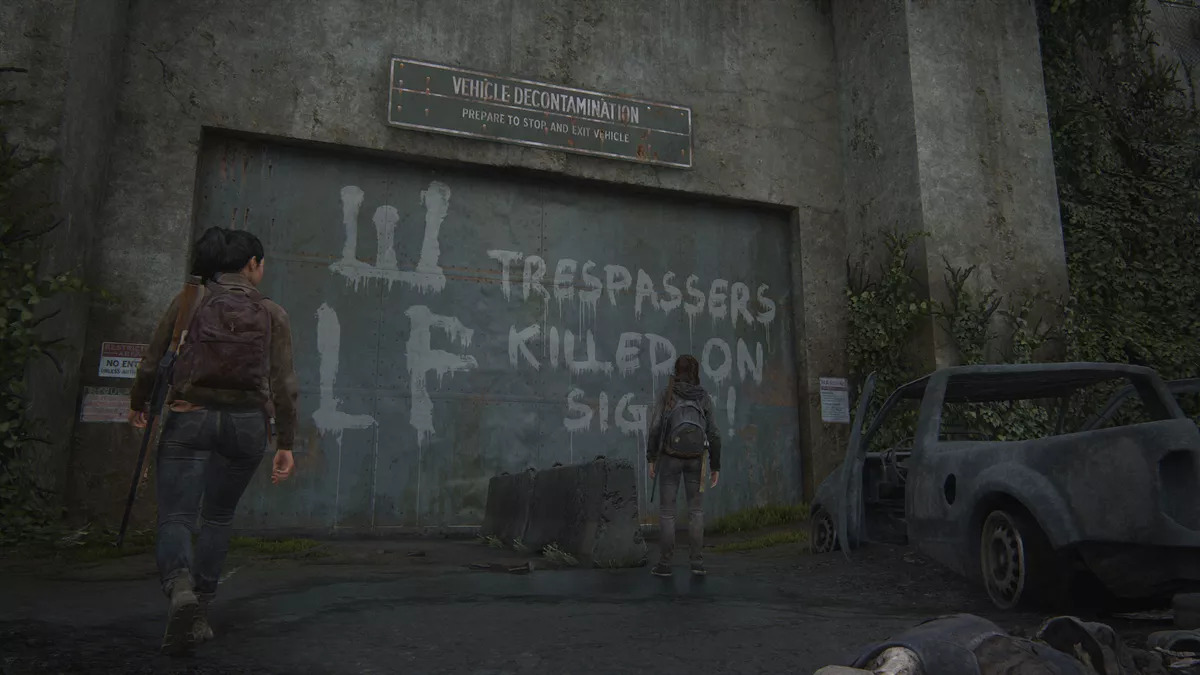

PART II centers around Ellie’s quest for revenge after her adoptive father Joel is hunted down by some out-of-towners with a chip on their collective shoulder. A parallel story follows the killer, named Abby, and her growing disillusionment with the Washington Liberation Front in Seattle that is engaged in internecine conflict with a religious cult called the Seraphites.

For being entirely and myopically about the consequences of his actions, Joel figures into the narrative only a little bit. There’s numerous flashbacks to resuscitate our connection to him and Ellie’s emotional stakes. But his supposedly-complex patriarchal specter rarely registered as significant to me over the brutal and present occasion of the game’s action movie themes, and seemed more like a side story in one that’s otherwise all about how people kill people after their people are killed.

If the designers worked to perfect gameplay for player gratification, even going so far as to carefully allow error and unfairness to meaningfully be a part of it, the writers worked to make sure that the player is never confused about why things are happening, or the meaning of it all, creating an unambiguous moral ambiguity. Here moral greys are not like a mixed accretion of white pigments and black ones, but how an artist might do it with digital tools: one whole white image and one whole black one, adjusted for opacity, layered on top of each other.

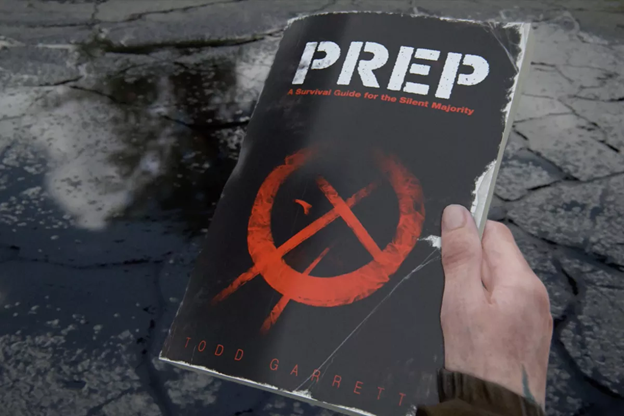

If the ramifications of the game’s muted and realistic tone are to be taken seriously, then to me humanizing Joel’s killers, problematizing a revenge narrative, is obvious before the fact. Dragged through it all regardless, micro-fiction in the form of letters eventually became the more interesting meaning-making things in the game. These highly functional storytelling artifacts had a shelf life as long as the environments they are found in, and though my lizard brain was driven to seek them all out, not one stands out now.

With THE LAST OF US PART II the form of mediocrity was tasked with producing something not mediocre. I can’t speak for Neil Druckmann, however much his loud title at credit’s roll has left him out for the mob, but to me more than any totalizing artistic impulse these narrative choices are all more readily attributable to the way imagination is permitted and denied through the factory gates of a corporatized production entity’s workflow, especially one with Walt Disney-like defined house style, when it is trying to strike platinum again for the sequel to their prestige series.

This is to say, that the corporate imperative is to gratify results in aesthetic choices, and that we can determine these with some precision, because this imperative is specific: aim for the least risky-to-hit lowest common denominator in an audience. The WLF, militant insurrectionists without an ideology, and the Seraphites, conducting rites and building shrines without meaning, are to my eye the more elegant narrative production of this machine.

A strange, delicately-realistic bauble that is nearly see-through, taking up the reins of the player-character to log another 45 minutes of her emotional journey, I rotate their object enough to admit into the arthropod mouthparts of my critic’s heart amendments to the game’s themes, that while people kill people when their people are killed, every person belongs to a people. I cluck my tongue; “tragedy.”

Recalling the ultimate imperative of the corporatized production entity, to strike with minimal risk the lowest common denominator in their audience, not being mediocre then means being considered as such by the most people. Picture every film that A24, a brand predicated on not being mediocre, has felt a worthwhile acquisition, boiling in a vat, the parts most people like getting distilled into a flask. Now smell the flask.

The WLF and Seraphites smell “complex,” “moody,” and “realistic.” Very-conventionally exotic artifacts of the science fiction genre, with only enough culture to remain operational within the corporatized production machine’s tripartite imperatives (gameplay, narrative, and not being mediocre), the WLF and the Seraphites are hollow all the way through. At some point of their crystal ball being rotated in the hand for study I realize I am mostly looking at my own hand.

Stepping even further back, it’s interesting (like how picking at scabs is of interest) to see the game, which rounds out its cast with diverse bodies, in an attempt to remain apolitical, build out, like how hung coats build out the shapes that are waiting for them on hooks, a very particular politics. The cordyceps brain infection has finally laid behind every blade of American grass a rifle.

In a post-racial post-apocalypse you’re either a farmer or a soldier, and everyone’s already a colonist. Chalk that up to the genre, which often posits vast cullings of the population by supranatural events, thereby preparing a terrain of “realism” for rejuvenated fantasies of settlement and civilization building. In the colonial outpost of Jackson, Wyoming, the role of bigotry in the organization of groups after the collapse of democracy is lampshaded by the enduring existence of one homophobic, but otherwise decent, old man. Folksy tolerance and individual hobbies (gee-tar making) provide meaning in the absence of shared communal ones further than survival.

At the workbench where you upgrade your weapons, a few hours of soaking up bloody realism culminated in highly-detailed firearm machinist animations, making me come to a frightening realization about guns: that a silencer is actually about creating a sound, not erasing one. The sound only has to be strange enough for you to be confused, just long enough for someone to get the drop on you, and for this purpose something as simple as a water bottle will suffice.

Why does any of this matter? Looting ruins as Ellie you find trading cards. Each has a character from a vast, expanded-universe-type intellectual property, science fictional and superheroic. Short biographies and stats are on the backside, quantifying brains, brawns, and the character’s place along the spectrum hero-villian. Playful and ironic, the writing successfully achieves a mimesis of the kind of thing we might find, back at our parents’ house because coronavirus has waylaid our lives, moving old boxes out of our childhood closet.

The cards fascinate me beyond being an ersatz digital facsimile of something I recognize. There are chimeric qualities to the imitation: a sense that what is being grasped after is more than just a reference to the role Marvel comics would play in the historical record. The cards are old: frayed and bug-bitten. The cards are unserious and unoriginal: they rely on familiar tropes. But in the context of post-collapse Seattle, in the context of an Ellie that is suddenly no longer a vehicle I operate but a character through which I am moving, they have more meanings.

It is like how in the game, going from cutscene to play, my understanding of allies, seeing them now under the lens of their function in play, temporarily pixelates what was specific and complex about them, as they become a dulled fixture of the combat arena, which I shouldn’t count on in order to get through enemy encounters. The space cops and solarpunk scientists on the cards are in a similar way “pixelated” by their function as collectibles in a post-apocalypse game. What I then read off of them is less “The biography of Dr. Uckmann” and more “a piece of science fictional writing.” What the card means is science fiction writing itself.

As player and character, my apprehension of the cards in their entirety has become the more apparent meaning, and, significantly, that entirety includes the world to which the cards once belonged. A world that likes to imagine worlds further than itself, of museums, aquariums, zoos, and Apollo 11.

In a very self-reflexive sequence, Ellie and Joel look at bones. The environments in a Naughty Dog game are fossilized, an architecture for the flesh of the player’s experience, visited one after the other, character-jeeps cinched to an amusement park track like JURASSIC PARK. The artists who make these possible do so largely in obscurity because there are no institutions today that preserve the knowledge of how to value the achievements of a collective, in addition to their being none that preserve the knowledge of how to value the aesthetic achievements of an individual, though I digress.

It is not difficult for me to imagine that, to certain developers working on this game, it would be the last video game ever made. They could have felt this way because inside them Naughty Dog’s crunch culture was ending their love of the work, snuffing out worlds where video games could be made from. They could have felt this way because they had been paying attention to what’s going on outside their workplace, beyond their ambitions.

If there must be a technological aspect to art, it would be in the mode of a translation device. Art preserves worlds of meaning, but as a kind of trickster instance of their re-arrangement, manipulation, and animation. You couldn’t just read the dead world back off of them straightforwardly.

The part of art that extends its radio antenna to the dead world is the fact that something willingly made it. Out of that fact I can observe the artifact, see where the marks were made, and render in my mind the hands, body, head of the maker. I can build the room where it happened. There should be a window looking out: a small one, since I want to be careful about scope creep…

Is it enough? Why does it seem like what I’ve rendered is a wire-frame animation in a cubic void?

A gift and a curse of science is that if people really are kind of all the same in certain respects, then it shouldn’t be incredibly hard to imagine the experience of people from a very different time and place.

From this idea science fiction rolls out, energetic, youthful, asking absurd questions out of which star treks and wars are born, rolling out more meanings in turn. People, places, things, and feelings about them get caught up in this constant unrolling. Counternarratives, subgenres, and deconstructions proliferate.

Labor is what is always at the searching spear tip points in this great human fractal-drawing animation. Whose totalizing shape is never finally seen, except by what is suggested in the repetitions.

Off the head of a wave we’ll try to read the name of this ocean. I’m reminded of piece of science fiction writing, read off the back of a trading card, which in a coffee-shop jeweled with the absence of human sociality, Ellie found dusty and whole:

“Big Blue is an extra-dimensional entity who has taken on the appearance of a blue whale. First arriving on Earth over half a billion years ago to keep watch over the nascent life forms, they use their infinite well of knowledge to help guide the human race in times of great need and upheaval. Their unfathomable age has one major drawback: days appear to pass as microseconds. However, this time dilation effect is offset if they hold their breath – which they can do for several hours at a time. 100 brains and 80 brawn. Affiliation: none.”

Comments