It’s been said—by glib people—that millennials are the “therapy generation.” The 2010s has witnessed a staggering increase in young people seeking mental-health help, matched by the growing number of diagnoses: major depression, anxiety disorders, etc. The therapist has indeed become a routine conversational figure—“I was talking to my therapist”; “my therapist said”; these are now fairly-common statements from millennials and zoomers (Generation Z). With a growing awareness of mental-health troubles in the popular culture—aided by self-disclosure from Hollywood celebrities, and the soapbox of social media—there is also a growing need for our movies to accurately reflect and depict those troubles that young adults are struggling with both inside and outside the consulting room.

Prior to the 2010s, entries in the mental-health canon were largely sensationalist, if they were there at all. One thinks of the exploitative GIRL, INTERRUPTED, or the similarly tone-deaf MANIC. Only recently, however, has the need for representation of what has come to be called “mental illness” become so dire. Young people like to see themselves represented on-screen, whether that be in the form of a shared diagnosis with an on-screen character, or through that character’s race or gender expression.

Beginning with IT’S KIND OF A FUNNY STORY (2010), through Netflix’s 13 REASONS WHY (2017) and Pixar’s INSIDE OUT (2015), and concluding with Sam Levinson’s EUPHORIA (2019) and Ari Aster’s MIDSOMMAR (2019), my goal is to contextualize the mental illness film, explore why some work and why some fail miserably, and what the goal of a film depicting emotional struggle should be going forward.

Before the big-budget spectacle of CAPTAIN MARVEL, in 2010 Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck turned their directorial gaze toward adapting a novel written by Ned Vizzeni titled IT’S KIND OF A FUNNY STORY. It is essentially an autobiography of the author’s week-long stay in the psych ward as an adolescent. Vizzeni, who published the book in 2006, and attended the film’s premiere in 2010, killed himself in 2013.

Emma Roberts and Kier Gilchrest in IT’S KIND OF A FUNNY STORY (2010)

FUNNY STORY doesn’t so much normalize the psych ward experience as it does romanticize the hospital as a sort of Eden inhabited by brilliant, tortured artists and high-maintenance but beautiful women. Craig, Vizzeni’s stand-in, and Noelle—a cutter and fellow manic—find love, as the film ends with the two planning to go to a concert once their stay at the hospital ends. We have no numbers on the amount of young adults hospitalized in the last decade or so, but the trends in depression diagnoses indicate that hospitalization in the 2010s is not uncommon. The young person watching FUNNY STORY may be led to believe that in the psych ward one will not only find salvation and purpose, but true love. As Vizzeni’s tragic suicide indicates, this is not the case.

Early 2010s cinema can be understood by acknowledging its relationship to the 2008 recession. Both FUNNY STORY and THE PERKS OF BEING A WALLFLOWER (2012) center very explicitly on suicidal ideation during a period when suicide rates skyrocketed. Lars Von Trier’s MELANCHOLIA (2011) is literally about a crash, albeit one that results in the destruction of all life on Earth rather than the temporary shrinkage of capital—which may be even more devastating. SILVER LININGS PLAYBOOK (2012), about two bipolar individuals, is rooted in class anxiety: the accumulation of money is linked directly with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (Robert de Niro’s superstitious antics deployed when betting on a football game).

Before the crash in MELANCHOLIA (2011)

Only when job levels rose to pre-2008 levels in the mid-2010s could we see more sophisticated depictions of emotional troubles. INSIDE OUT should be commended for introducing an accessible framework with which families could talk about emotions. In fact, it was such a success that it seemed, going forward, there was no more room for stories dealing with the potentially exhausting topic of depression. With the exception of 13 REASONS WHY, the major mental illness films in the latter part of the decade focus on less recognizable disorders (TO THE BONE and eating disorders, WELCOME TO ME and Borderline Personality, MIDSOMMAR and bipolar). Part of this may also be because as the rapidly expanding streaming services cascade toward an unlimited supply of content, there is available space in the market to make works about somewhat niche topics (e.g. TALL GIRL). Netflix released TO THE BONE in 2017 about a young woman suffering from disordered eating. As these opportunities to explore neglected issues arise, we must be increasingly wary of their execution; the tweeness of TO THE BONE, along with its near-monopoly on eating disorder cinema, risks ending the conversation before it’s even really begun—especially when the only other film to try and tackle this subject was Jason Reitman’s deeply unsatisfying and wholly misguided MEN, WOMEN & CHILDREN.

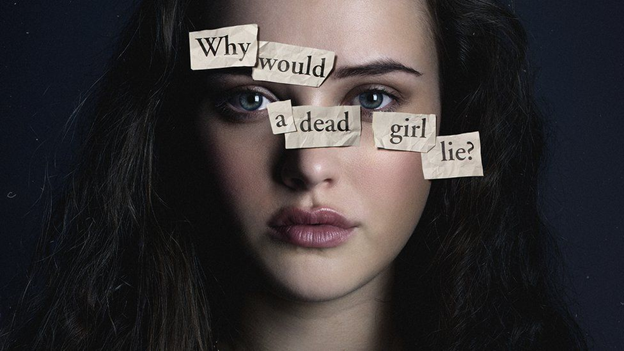

13 REASONS WHY debuted at the time when a Netflix original series was still a somewhat prestige event, and it is a particularly egregious series for visually depicting 17-year-old Hannah Baker slashing her wrists. The scene in question is one of the more disturbing things you’ll ever see; it is absolutely and needlessly grotesque. In fact, you can’t actually find that scene on Netflix anymore—in July 2019, the company edited it out, buckling under criticism from mental health professionals (more than two years after the scene first aired in the series’ first season). A study in 2019 found that the suicide rate amongst young people increased by 28.9% the month after the show’s debut.

A promotional still for 13 REASONS WHY, featuring the words “Why would a dead girl lie?” plastered in scrap paper over the face of a character who has committed suicide

The data strongly suggests a causation. 13 REASONS WHY’s mistake was not understanding the psychological effect of the closeup shots of Hannah Baker opening up her wrists. The reasoning was something along the lines of “we need people to see just how gruesome, bloody and messy this act really is. Maybe then they won’t be tempted to do it!” Netflix, that benevolent practitioner of aversion therapy, failed to realize that the closeup makes the subject matter inherently enticing and vaguely romantic—the closeup is interested when it should be dispassionate. What seemed like a surefire way to singlehandedly ruin suicide’s gravitas backfired horrifically.

I don’t mean to harp on this one Netflix project, but it is necessary to recognize that the visualization of a particular disorder is perhaps more important than its narrative vessel. HBO’s EUPHORIA takes an interesting approach by actively celebrating and indulging in the effects of hallucinogens and downers and uppers the characters pop like Pez™—which some have claimed is irresponsible. The camera will flip upside down, as the set rotates, to hammer home the idea of an altered state. But EUPHORIA does something 13 REASONS WHY could not be bothered to: contextualize the characters’ mental illnesses. What is for all intents and purposes a short film plays before each episode providing backstory for one character who will serve as an anchor of sorts for the next hour. By offering glimpses of the character’s childhood, we can better understand why substance abuse, rage, and anxiety now dominate that character’s present condition.

A typically trippy scene from EUPHORIA (2019)

And that, I suppose, is the most important thing. MIDSOMMAR is about two sisters struggling with mental illness—one of whom is confirmed to have bipolar and kills herself and her parents in the opening reel—but is sorely disinterested in whatever occurred in these girl’s childhoods (assuming there’s some greater context to gassing yourself and your folks), which fails to make the later horror antics effective. I’m not saying there needs to be flashbacks to what happened or something overly showy; often a few well-timed lines of dialogue will suffice. If one is making a film about mental illness, it is artistic negligence to omit mention of the circumstances that have brought the character to their current state. Doing so leaves an audience unable to understand the character and that should never be the goal in a film designed to portray an already inherently alienating and oft-obfuscatory emotional state.

After the 13 REASONS WHY tragedy, there is no reason not to believe that a poorly-conceived movie or series dealing with mental illness can literally kill. Sadly, young people need no help in that regard; from a recent article in the New York Times: “the suicide rate among Americans ages 10 to 24 jumped 56 percent between 2007 and 2017.” We can’t be sure exactly why young people are killing themselves. Perhaps it has something to do with the climate apocalypse no one is doing anything about, or the constant, debilitating headlines of mass shootings at schools coupled with the fact that, due to a broken health care system, young people cannot afford to seek help.

As artists, we often feel powerless. Even when we couldn’t make our intentions clearer about what we are trying to say, the message sometimes, somehow, depressingly, gets lost in translation by those who need to hear it the most. That does not mean it is not worth fighting the good fight. A film that communicates something intimate and does so intimately will inevitably connect with a lost soul who is yearning for precisely that. A good movie about depression, anxiety, bipolar, schizophrenia, etc. can bring hope to those who suffer; it can remind them, through Ebert’s idea of cinema as a machine that generates empathy, theirs is a struggle that is not hopeless. People can even make movies about it.

That is how not hopeless it is.

Comments