By the time my parents’ marriage crumbled, I was a boy of five or six. The prevailing hypothesis—supported by many a childhood researcher and psychologist—is that divorce at such a malleable life stage has a similar effect as chucking pebbles at riders in the Tour de France. It frays the child’s relationships with both parents, impedes cognitive maturation, and often leaves emotional landmines to be discovered in adolescence and adulthood. (Personally speaking, that’s a maybe, yes, and a solid hell yes.)

I merely recall that warm glow of hope.

My memories from the marriage are mostly shards — a screaming match here, an awkward span of silent disconnect there. So when it ended, my incomplete little brain quickly let all that psychic garbage go, and it dissipated into something bordering on optimism. Even as I was made to pour my soul out during weekly therapy sessions, I felt as if it’d all be OK—that my parents had been efficient in their actions, and saved us from heaps more heartache. And also that I wanted to play with the doctor’s wooden bricks forever.

In childhood development circles, there’s this idea of resilience. Kids with the right coping mechanisms — and meaningful support from adults in their life — can bounce back quickly from even the worst traumas. It takes a special kind of awareness and determination within kids to see a divorce — the end of the very concept that unfurled your existence — and learn to cope with that in a healthy and productive manner. And if I never had those skills, then maybe it was the autism as a mighty defense barrier.

—

Regardless, what I did have was Rick.

My mom and Rick started dating within 10 months of my dad moving out, although the timing and our familial bonding made it seem as if he was always in our lives. This big, broad man, who looked like The Thing before he went and got mutated by space rays; these dense, muscular forearms he used to pull you into the air; his voice equally stoic and masculine, with a slightly Southern drawl despite living most of his life in the Southwest. He was a rock of a man in every sense of the word, and he made my mother shimmer with a joy I hadn’t ever seen before. You could see it in her face and smell it in her hair when she’d dole out hugs: she’d found whatever echo in the Universe she felt she’d been gifted by God, no matter how harrowing the journey.

When they got married, I was utterly elated. The ceremony took place in the house of my mother’s best friend, an upscale abode with massive stairs and pristine white walls and a sprawling backyard with a pool and jungle gym. Dozens of people crammed themselves into the living and dining rooms, and my brother and I ushered my mom down the stairs, counting every step of the journey toward something bigger. It was a day for my mom and Rick, but I took a special pride in giving her away—a blessing made physical, literally placing her hand into his in the hopes he’d give her the life she’d always craved, one of wedded bliss and family gatherings and barrels of quiet romance.

—

For those first few years, Rick remained a man of his word.

My earliest concrete memories began to form, of which I used to trace an outline of a life and a self and a sense of the world: a picturesque child one assumes to be the foundation of a cohesive, well-adjusted adult. Camping excursions in the high deserts. Days spent hiking outside the boundaries of time and city life. Family dinners with huge steaks and massive racks of ribs, conversation mixed with silly faces and fart noises. Long drives in his massive blue truck, darting around the city or coming back from a day at the lake. Most of all, the music.

It’s with no hyperbole in admitting that I wouldn’t be the man I am today — a devotee of pop music and someone who has made his living dissecting songs and albums —without the sage guidance Rick provided. He was my gateway, not just into specific bands, but a way of thinking about music. During long summer evenings when the Arizona sun practically crawled to the horizon, Rick would put on a master class of sorts. In the living room of our home, mere feet away from my room and the backdoor, he’d crank tunes made for cooking or drinking a beer or just dancing through the halls.

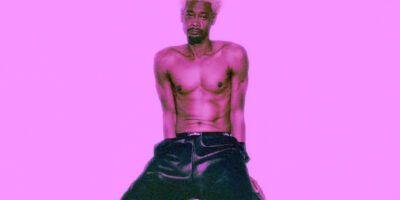

One day, and I recall my mother being in a foul mood, he played Deee-Lite’s “Groove is in the Heart.” The bassline was truly revelatory, and I recall feeling my childish insecurities dissolve as the whole house filled with the soulful croon of Lady Miss Kier. It was as if our little home had been transported to some dancehall orbiting a distant star, and even my mother’s mood vastly improved thanks to the song and our little impromptu “Soul Train” across the carpeted family room. This was a moment of pure bliss, a perfectly crystallized demonstration of how music could reach into the deepest holes and pull you into the world. My eyes were opened, my ears were on fire, and my heart was aflutter every time that intro boomed.

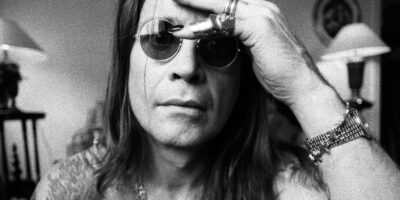

Rick’s taste may have included dance and pop, but he was a rocker through and through. He’d crank some Wall of Voodoo with just as much frequency. Any child who hears “Mexican Radio” before puberty sets in will be forever transmogrified. If Deee-Lite opened my heart to the power of a good bassline, then Wall of Voodoo kicked down the doors to my burgeoning personal aesthetic. This goofy song spun me around with its catchy chorus, hodgepodge samples, and unwavering absurdity. I learned in a few minutes that music could be very weird and just as impactful, that the best songs spoke a language that was only for the kooky and disenfranchised. For a kid struggling to figure out who he was and why a barrier existed between himself and other kids, this was like Superman learning about his rocket ship crib.

Even with Deee-Lite and Wall of Voodoo on non-stop, nothing held a more prestigious place in Rick’s musical queue than Cake. Here, the lessons of the other groups were enhanced and distilled to a potent clarity. Cake’s blend of old folk, surf rock, dense lyrical references, oddball aesthetic, and endless energy echo through me to this day. I feel as if every great song I’ve found and added to my heart is just a way to fill that initial crater left by “Frank Sinatra” or “Italian Leather Sofa.” A friend told me once that every young man has an affinity for Led Zeppelin at some point. I never did — maybe I’m not a real man because I only dig “Immigrant Song” — but Cake accomplished that very same world-forming and taste-making. They blew the hinges clear off and made me understand that great music was as undefinable as it was deeply familiar. That who we are is about living in the world, spinning together threads of ideas and feelings, and making something great from that experience. Mostly, they made great songs that made my little family very happy.

No matter what Rick spun, there was an intense passion always at play. If he were to attend a concert, he might have been the guy in the back, gaining new life every time the familiar riff of a hit song began. He was unabashed in his commitment to good music, and he chose to express himself in a jovial, wholly physical way with the songs that spoke loudest to him. He was a fan in the most essential and purest fashion, and that had an influence on me. I’ve tried to consume music in a way that honors that earnestness, to not just be unafraid of boundary lines and a grand consensus, but to try and get other people to listen and groove alongside. In turn, that’s filtered into the way I write about music and culture and life — with a simplicity that emphasizes a commitment of genuine understanding and a willingness to find the joy in all things, no matter how that translates.

—

Cake has a song called “End of The Movie” that starts plainly enough: “People you love will turn their backs on you.” What they don’t sing about is the subtlety of said betrayal, how love and happiness can evolve into anger and outrage in a way you could never visibly detect. A few years into the marriage, the family started going to Al-Anon. Through the process, we were told of Rick’s struggle with substance abuse, and his desire to kick the junk and make our family even better than before. We’d drive to some plain-looking treatment center, and while the adults engaged in intensive talk therapy, my step-brother and I would hang with other kids and mull over our nebulous feelings over art projects and frozen juice boxes.

Even in this time, when everything felt raw and exposed, music was still a big enough deal. Smash Mouth’s “All-Star” and Chumbawamba’s “Tubthumping” somehow played in a near-loop on drives to and from therapy, thanks in part to repetitive rock radio and our own collections. These hugely catchy songs forced you into singalongs or made even the largest SUV feel cramped if you somehow resisted (as one might after a long evening of hoarse screaming and crying). Where music had once been a powerful facilitator of dance parties and cookouts, it now weighed down this family unit—a most unfitting soundtrack to a bitter period marked by slamming doors, endless threats, and a sense of gut-wrenching uncertainty.

Soon, the music stopped almost entirely, and with it came a pivot into truly nasty territory. Despite earlier promises, whatever substance had its claws in Rick’s neck was canceling any attempts at therapy or my mother’s pleading. Rick’s behavior took a nasty turn, and I’d walk into rooms to see her backed into a corner, him snarling about her weakness despite him being the one with a cash-consuming addiction. The official end came when he blew up at her during a camping trip, and with a precision and grace I am in awe of to this day, my mom returned fire, debunking every selfish thought he fired her way. She and I left camp a couple hours later, and I recall being in the car for a two-hour drive and wanting to hear the radio, even if it was talk radio or static hum. But silence guided us back into the Valley of the Sun in record time.

Even with everything that had happened for the better part of a year, I held onto their relationship with a special brand of optimism. As a young teen who spent much of his life obsessed with pop songs and comic book heroes, I thought we might fight our way toward a happy ending. We could beat that skull-faced villain called addiction, rend our rifts with Cake songs and deep-fried potatoes, and become a family once more.

The real and true ending, at least for me, happened shortly after the camping fiasco. Rick had mostly stayed away until then, but he came in like a fiend one day, yelling and screaming about money and my mother’s endless sabotaging. I did something I never had before — I stepped in front of my mother, crying and shaking hysterically, and this beast of a man. It took little effort before he sent me flying over a coffee table, and as if instinctually, I was back on my feet and in his face. A profound beating he promised never came to pass, and Rick high-tailed it almost immediately thereafter. What smarted more than my pride or lower back was the sudden and acute awareness that there was no saving what had been, and that maybe this whole time — beyond the rock songs and play wrestling and summer barbecues — this may have been who Rick was all along.

—

As existence marched on, I never quite let go of my relationship with Rick. For years, the thought of him made my blood boil, and I wished (to anyone who’d dare listen) for an opportunity to pull out his teeth — through the soles of his feet. Those thoughts cooled as I got older and learned the value of patience and the idea that manliness , and really, adulthood in general , is about turning the other cheek for the ones you truly love—and always yourself. It helped that my mom got remarried, this time to a hard-working, salt of the Earth type, a man whom I had grown to admire and respect despite a musical taste seemingly stuck in the late ‘70s. Yet what I’ve never been able to shake fully, despite my rage cooling into a general apathy, is what to make of Rick’s larger influence. It’s a thing I’ve thought about a lot when, in late August 2023, his son told me he’d passed away from cancer earlier this summer. What do they say about the song remaining the same?

My thoughts, though, mostly tumbled backward. Like, there was a moment at Street Scene 2009 where, after running through the festival grounds, I made it just as Cake took the stage. As the sun bore its full weight, and the wafts of pot circled me in several criss-crossing airstreams, I thought about what the band meant to me, and how I’d been gifted them in the first place. I had all these complicated feelings toward this man, and yet the first note of a Cake song, or some random bar from Smash Mouth, would whip me into something not quite nostalgic, but a hazy glow that seemed to forget his destructive path through my family in favor of an earnest affection.

The closest analogy I can think of is what happens when you date someone. In the course of your relationship, there are songs that prove essential to your bond. Tunes that not only define how you feel about one another, but mark important moments, like a first kiss or when you jam out while making one another omelets. Love affairs are a collection of songs, perfectly encapsulated moments or sentiments, played on repeat for years at a time until the dance is over or the club closes prematurely. When these relationships end, people can struggle with maintaining a relationship with the music, just as I have

Kate Flynn wrote a great essay for Consequence about reclaiming Bright Eyes tunes after a bad breakup. She mentions this idea of her obsession with songs facilitating this, “single-minded determination to keep those memories alive” — like music holds itself over you and prevents you from only seeing the world through heart-colored lenses. What helped for her was developing a sense of humor in the face of all that drama:

“I needed to realize that in the same way that every YouTube artiste was just borrowing ‘Lua’ for a while to take their best shot at making it their own, I didn’t have a monopoly on heartbreak, on the undeniable devastation of being dumped by someone you love and who has told you many hundreds of times that they love you in return. I could cover it all I wanted, but sooner or later I would have to move aside to let someone else try.”

Writing for Buzzfeed, Nichole Perkins had a slightly different approach:

“I don’t know how much love remains for my exes, but my relationships with the music we shared had to change, if I wanted to take back control of those songs and how they made me feel. I know now that the highest level of intimacy I can share with someone is listening to Prince with him, and not everyone is worthy of that gift.”

Together, these two pieces highlight the importance of choice. That is, no matter how hard love (and, in turn, these very songs) may strike our soft, squishy innards, we have the power to re-contextualize them. To transform the meaning around these songs in a way that suits your newly-single needs. A song you and your partner played on your anniversary can, given enough time and distance and emotional maturity, turn into your jogging anthem. There is an inherent impermanence to romantic partnerships — which lets people retain a shred of power when we feel helpless amid the crushing weight of an old playlist. We choose how these songs contain meaning because we make those decisions everyday.

Yet my journey’s simply not the same. For me to try and re-box these songs/artists is to do away with the very nature of my music-loving essence. They are who I am in many ways, both significant and not, and I have little desire to try and re-spin their meaning. I feel a devotion and gratitude to these constructs that is as elemental as my love of reading and my flat feet. It’s not that I hold these songs in higher regard than, say, Flynn or Perkins. Rather, I feel as if these tunes are hardwired into my brain in a way that makes them almost impossible to remove (like scrubbing the last bit of shark DNA from humanity). All of this music’s tied to memories and feelings and ideas that make me who I am, and the idea of changing them invites a sense of existential dread that leaves me feeling woozy. In some regards, I may enjoy the echo over the actual songs Rick played ad-infinitum.

—

Listening to this music more recently stirs within me a sense of intimacy I’ve long tried to banish. Note one of Cake or Deee-Lite hits my outer ear, and I become that optimistic boy once again. The kid who felt the transformational power that great songs had, a gift once promised by a decent man. That life never made it out of the early stages, and I can’t deny that my existence has taken a different path. One where my mother and I struggled to find closure from such predatory heartache. A life without the promise of warm summer days on the beach with family. But also one that’s infinitely better, where she found the love she wants and I’ve grown to see the world in a way I can’t help but feel is well-rounded, if not mildly depressing at times. And even as our own relationships have evolved and sometimes (and most recently) become strained, that same dynamic remains steady.

In a way, my heart has outgrown the keepsakes it once thought were so real, and this music just stirs up emotions that are not viable in this world (if they ever truly were). At times, I feel frustrated, as if it’s all a string of memories denied of any positive spin, leaving only bitter resentment. I share in the ache that Flynn or Perkins talk about, yet find myself stifled by my uncertainties and my apprehension for organic change.

Yet I love these songs dearly, and so I must find a way to deal. Not to find new life for them, or brand new space in my head and heart. Rather, to let them sit there like some ugly, unmovable couch that I am simply forced to live with. That I can use them and hang stuff on, even if it becomes a big, crushed velvet sore spot cluttered with hurt feelings, broken promises, and lost time. That maybe I won’t ever get over the presence of these sentiments carried by three-minute pop songs, but that one day it’ll fade to the background. It’s not the most optimistic perspective, but it does contain a nice mix of reverence and stoicism that fits my unique relation to all this ephemera.

I listen to these songs and a notion becomes clearer over my memories. The more I live the way I want — loving the right people, eating the best foods, working in a meaningful way, etc. —that mound won’t feel so heavy. That the rest of the emotional objects in my life – built of and enhanced by songs or other cultural artifacts —can become the focus of more meaningful reminiscing. One day, when there’s been even more time and growth, some of the gifts Rick gave me might feel like just that — treasured items that make me overjoyed and appreciative for their mere presence. If nothing else, I’ll make peace with them in a way that I can actually find value with.

Or, per the sagely wisdom of Chumbawamba, “He sings the songs that remind him of the good times / He sings the songs that remind him of the better time.”

Comments