Any highly-anticipated release from genre-defining musical artists forces us, consciously or not, to reminisce on their canon, not only what it sounded like—the “classics” and whatnot—but what it said then, what it says now, and what it could possibly lead them to say in the future. Maybe, somewhere in that line of questioning, we may be able to make sense of the change in-between. My mind keeps wandering back to the suspense of Frank Ocean’s BLONDE, knowing full well it would never be able to reinvent the world of CHANNEL ORANGE, and yet still hoping its magic would translate into another similarly beautiful language on the new record. Naturally, a fan would hope that Vampire Weekend, a band conceived while all its members were studying at Columbia University in the early aughts, might reimagine a way to ruminate on the very slippery post-graduate suspense and metaphysical questions that characterized their first three albums. And considering their consistent success, it’s fair to hope for an ambitious-but-recognizable sequel to the bildungsroman of VAMPIRE WEEKEND, CONTRA, and MODERN VAMPIRES OF THE CITY. Having explored many of life’s biggest questions in the trilogy, it led me to wonder what territory the group might unearth on their latest release, FATHER OF THE BRIDE.

I’m driven to this investigation not just because I’m a fan of the band, but also because Vampire Weekend have stirred our metaphysical confusion since their inception. As it has been repeated in the discourse, their sonic trademark places the listener at once on a yacht off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard, and also in the social hour of an Afro-Caribbean village; at the glittering country club and also on a murky river floor. At one moment you’ll taste surf rock, another baroque, and the next, rara. The lyrics are famously shrouded in witty critiques about class politics, foreign policy, privilege, guilt, and often disillusionment with it all, as frontman Ezra Koenig repeatedly flashes his English degree with never-ending cultural and historical references. The time and place is a blur, the only constant perhaps being the sun burning above.

Always cerebral, it’s not usually easy to tell where they’re landing on the timeline, philosophically hopping from Leibniz to Kant to McTaggart. And how could they not? The Vampire Weekend album trilogy was born and raised through the band members’ 20s, the most embarrassing decade to be pondering our graduation from adolescence and nascent assimilation into the so-called “adult world.” At that point, the past is foggy from our primitive, childlike memory, and the future seems infinite with possibilities. In the present, it just so happens, almost by accident, that whoever we are and whatever we’re doing right now is what’s reality. Koenig says it best on “White Sky”: “A pair of mirrors that are facing one another / Out in both directions, a thousand little Julias / That come together in the middle of Manhattan.”

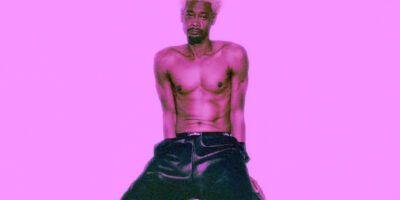

Where does the clock stop six years after the trilogy? Are they still cruising Cape Cod? No—they’ve traveled since then. Chris Baio and Chris Tomson both released solo albums, Ezra Koenig made an anime and became a father, and Rostam Batmanglij—Vampire Weekend’s songwriting heartbeat, production connoisseur, and multi-instrumentalist—left to pursue ambitions in solo work and producing credits. We cannot expect the same old-same old from them, so thusly we’re presented with this conflict of time versus change, a clash with which the band are all too familiar. “Giving Up The Gun” from sophomore album CONTRA especially considers the likelihood of being able to give up present technologies to “go back to a simpler way of life”:

But if the chance remained to see those better days,

I’d cut the cannons down

My ears are blown to bits from all the rifle hits,

But I still crave that sound

Without necessarily recreating the past, but with enough creative and financial freedom to experiment and compound upon their previous work, where does Vampire Weekend eventually land on FATHER OF THE BRIDE? We might get closer to an answer by looking at the canon itself.

A collective self-referential orgasm was felt ‘round the world when fans heard the FOTB single “Harmony Hall” sing back, “I don’t wanna live like this, / But I don’t wanna die,” a paradox interpolated from MODERN VAMPIRES OF THE CITY’s punkish and batty “Finger Back.” The latter, saddled by three other songs of religious query, recounts a Romeo and Juliet love story between an Arab falafel cook and an Orthodox Jewish girl, the lyric in question apropos to choosing love over faith—an existential dilemma that anticipates a formidable judgment day, somewhere after death. But “Harmony Hall” reframes the paradox, this time fearing the trap of angry echo chambers, while the end of such cycles could mean letting one’s guard down, and thus death. This seems significant because the FOTB lyric marks a departure from the narcissism of the band’s earlier metaphysical questions—Who am I? What is my purpose? Where have I been and where will I go?—and instead suggests a more noble concentration on the present and the actions possible in the current moment.

It’s one of those things that music writers love to geek about—a fixation on death that’s masked by instrumentation that otherwise fools us. Koenig is no stranger to such questions or juxtapositions. In one Esquire interview, he mused on the idea of watches being both a measure of wealth and “the one thing that money can’t buy . . . time.” He goes on to say:

There’s something almost tragic (or hilarious, depending on your sense of humor) about a French millionaire cradling this fancy toy that simultaneously flaunts his status and ticks on toward the ultimate end of status—death, that great equalizer.

How better to express his unease with this relationship than in MVOC’s dreary dirge “Hudson,” a clock literally ticking in the background like it’s counting down to doomsday. Time, flowing like the uncontrollable waves of explorer/colonizer Henry Hudson’s eponymous river, takes dear old Hudson’s life away. Beyond “Hudson,” Koenig continues to sit and wait for that fateful day—

If I wait for a holiday

Would it stop my fear?

To go away on a summer’s day

Never seemed so clear (“Holiday”)

You could even say it’s only just a matter of time! But why all the anxiety about what’s ahead? The band’s stereotype has always suggested otherwise—Koenig cites the satirical “Official Preppy Handbook” in a blog post from 2006, a tongue-in-cheek book that posits the first common sensibility of prepdom to be ennui, “a feeling of utter weariness and discontent resulting from satiety or lack of interest.” This dissatisfaction somehow remains consistent through the Vampire Weekend canon, the self-titled’s “Oxford Comma” being the most obvious:

Who gives a fuck about an Oxford comma?

I’ve seen those English dramas too; they’re cruel

So if there’s any other way to spell the word,

It’s fine with me, with me

Again, they return to this apathy on “California English”:

Fake Philly cheesesteak, but she use real toothpaste

‘Cause if that Tom’s don’t work, if it just makes you worse,

Would you lose all of your faith in the good Earth?”

But that’s part of the band’s ironic charm—their jadedness is not a result of being prep, but a disillusionment with the culture of prep and its bourgeois populace. They’re actually just waving their arms in panic over the future and the vaguely-foreseeable ills that the preps are too busy using “summer” as a verb to notice. Remember “Diane Young”?

Nobody knows what the future holds

And it’s bad enough just getting old

Live my life in self-defense

You know I love the past, ‘cause I hate suspense

In fact, its visuals pay homage to Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 black comedy WEEKEND, a film about chaotic youth revolutionaries whose drift and unrest cannot be resolved, not even with money (sounds pretty prep to me!). Yet FOTB markedly refocuses this tedium to increasingly condensed scrutiny:

What’s the point of getting clean?

You’ll wear the same old dirty jeans

What’s the point of being seen?

Those eyes are cruel, those eyes are mean

What’s the point of human beings?

A Sharpie face on tangerines

Why’s it felt like Halloween since Christmas 2017?

. . .

How long ‘til we sink and it’s only you and me?

The question, on FOTB, no longer exhausts itself with self-involvement. Instead of worrying so much about his own path and his own demise, Koenig broadens the subject, and in that way clears a path to engage in a conversation that suggests community and its actionable projects. Metaphysical questions are amusing if you want to galaxy-brain yourself and annoy every business administration major in your Philosophy 101 course, but even if we could prove any theory of time, it simply doesn’t change the reality of how our societies function. Life and our reality is what it is, whether or not all the products and symbols that give our life status falls away, and whether or not we’re damned after death. It’s not worth it to “live [your] life in self-defense,” because living that way is a dead end (literally and figuratively!). So it seems significant that Koenig’s view is shifting out of himself and into more productive occupations.

In that respect, an especially relevant feature of FOTB is its messages about environmentalism and the looming climate crisis. But the difference between this theme and the foreboding of Vampire Weekend’s previous work are the tangible, possible actions that exist to make a difference in our ecological future (climate deniers and conservative administrations notwithstanding). Koenig opens “Bambina” with the lyrics, “No time to discuss it / Can’t speak when the waves reach our house upon the dunes / Time cannot be trusted.” Sometimes it’s just an allusion to conveniently reference more interpersonal designs: “Suddenly it’s much too late / The rising tide’s already lapping at the gate” (“Flower Moon”). And other times the tone is more quirky than sinister, like it’s just a matter of inconvenience: “We can live down in the flats / The hills will fall eventually” (“How Long?”).

Herein lies the weakest link on FOTB, however. There’s a moment in the happy-go-lucky track “Stranger” where Koenig sings, “I used to look for an answer / I used to knock on every door / But you got the wave on, music playing / Don’t need to look anymore,” the context here being the peacefulness of familiar company and knowing you’re not alone in your house. But it brings to mind how the trilogy felt like he really was knocking on every door intellectually, Koenig’s continual discontent with life’s biggest questions and his excavation of them through so many lenses unfurling like a rich tapestry of thoughts and images. Is this not exactly what kept Vampire Weekend’s past work from being just another indie boy band indulging in their egomania?

Aside from these vague references to the planet being on fire, and some milquetoast lines about political unrest (“Something’s happening in the country / And the government’s to blame” – “Married in a Gold Rush”), it’s unclear exactly how “grown up” we can consider FOTB when, thematically, it’s the musical equivalent of a shrug emoji. Ideations on his more personal relationships are similarly lukewarm, and though it’s commendable for Koenig to take a stab at being more straightforward in his lyrics, they’re musically framed with a simplistic mimicry of country music (“Hold You Now,” “Rich Man,” “Married in a Gold Rush,” “We Belong Together”).

In other words… FOTB just doesn’t share any interesting ideas, and many of the production elements that attempt to make it more interesting read like it’s a children’s CD (my ears cannot unhear the goofy shwoops and slide whistles that pepper “How Long,” or the “Margaritaville”-posturing of “This Life”). Thematically and musically, FOTB is more jaded than any previous album, except this time in a way that throws in the metaphysical towel and says, “That’s just life, kiddo!”

The existential dread and preppy ennui of Vampire Weekend’s past makes for more stimulating musical and thematic fodder than shaking your fist at the sky like an old man crying, “But here comes the sun / Those toxic old rays” (“Spring Snow”). The tracks that work the best simply ended up taking the most risks—the lounge-y and sincere remorse of “My Mistake,” the flamenco gunfighting of “Sympathy,” and the syrupy, Brazilian jazz of “Flower Moon.” Nevertheless, a lack of any strong convictions cause the album to fall short as a whole. All of Koenig’s past fixations have been watered down, not even into more digestible morsels of his former neuroses, but rather into tepid and jejune half-thoughts that give up before they even taste the meat of the query. Examinations on death have gone from dreadful (“Unbelievers”) to inoffensive (“Jerusalem, New York, Berlin”). Observations on class divides have gone from critical (“Mansard Roof”) to apologetic (“Rich Man”). Religious qualms have gone from confrontational (“Ya Hey”) to circumspect (“Big Blue”). And the most disappointing of all is following up achingly poignant love songs like “I Think Ur A Contra” and “Hannah Hunt” with… whatever the hell “Spring Snow” is. Koenig’s more “straightforward” approach to songwriting on FOTB, frankly, reads more dispassionate than personal.

A lot of life can happen in six years. Considering the breadth of work and collaboration that each original member of the band have produced since MODERN VAMPIRES OF THE CITY, it was reasonable to hope that this current phase of Vampire Weekend would produce a sharp, adventurous new album that reflects all the life one can live in that span of time—all the new questions that can arise when one is faced with the ever-mutating challenges, triumphs, and discoveries of becoming a more fully-formed adult in the world. But the past, undoubtedly, cannot be recreated. It’s a shame to walk away from FATHER OF THE BRIDE feeling more confused by its overall product than to be stimulated by the content of its cogitation. Alas, our metaphysical questions continue to go unanswered.

Comments