When should a game’s “final review” be written? It’s a question that still hasn’t been put to bed in the world of video game criticism. In an industry where a game can be updated, added to, fixed, reverted, and even disappeared completely thanks to the constant connection a console or computer has with the internet, the proverbial finish line of launch day is consistently blurred. Consider CYBERPUNK 2077, which cratered upon impact with reports of crashing, stuttering, broken models, and bizarre soft locks that made the highly anticipated RPG shooter an absolute chore to sit through. Or even the release of ASSASSIN’S CREED: UNITY, whose graphical issues made for Cronenbergian screenshots that continue to haunt Discord servers and message boards to this day. It’s a frustrating phenomenon, and some would even accuse it of being a business model in an industry that is as motivated by numbers going up as its consumers.

Earlier this July, Game Developer reported that the game WHEELS OF AURELIA would be delisted from the Apple Store due to a lack of recent updates and its download numbers falling below a minimum threshold. Delisting games like WHEELS is apparently in line with Apple’s policy toward games in its store, along with games that are either “nonfunctional” or “outdated.” In response, the game’s developers at Santa Ragione made the game free to download in order to get it out to as many players as possible while they attempted to appeal Apple’s decision. Santa Ragione co-founder Pietro Righi Riva responded thusly:

“We firmly believe that removing fully functional artistic works simply due to infrequent updates undermines the value and sustainability of games as cultural and artistic products. Like books, films, and music albums, video games represent complete creative works that do not inherently require continual updates beyond maintaining basic functionality.”

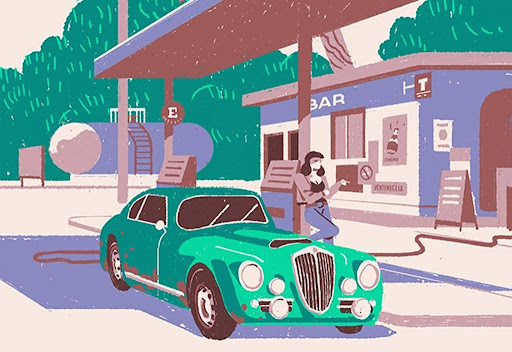

WHEELS OF AURELIA was originally released in 2016, and I remember this because I reviewed it in 2017, back when Merry-Go-Round Magazine was still largely based out of Santa Ana and under a different name entirely. We were young then. A group of recent and semi-recent college grads with big dreams, empty pockets, and very strong opinions on Adam Sandler. I don’t remember where I picked up WHEELS, but I was attracted to it because of my proclivity for Italian culture. My last name, my study abroad experience, Hell, even my minor are all based in the boot, as it were. But as I was writing my review for WHEELS I was sure that I was going to be Very Funny online while carving out a place for myself in the entertainment industry of Los Angeles along with the rest of my cohort.

The game that I played was an earnest road trip simulator, driven less by the cars that populated the ancient Aurelia Strada Statale and more by the folks that our punk protagonist Lella met on her journey. During the game Lella and her passengers muse about their lives, their futures, and the state of Italy in 1978 at the height of the violent Anni di Piombo or Years of Lead. This was a period punctuated by violent terrorist attacks by Communist and Neo-Fascist organizations, including the kidnapping of Prime Minister Aldo Moro and the detonation of a bomb at the Bologna Centrale railway station that killed 85 and wounded over 200. Suffice to say, there was a lot to talk about for the average Italian hitchhiker in 1978, and a lot to keep quiet about.

I recall that I compared it to a visual novel, and indeed some of the most consequential gameplay is what the player chooses to say or not. Some of it is idle chatter, but it also deals with things like identity, motherhood, ideology, and other subjects you don’t want to be stuck in a car talking about with a stranger. It’s a quick game, intended from release to be a game that one plays again and again, picking up different hitchhikers, going to different cities, and saying different things to get different endings.

In all the years it sat in my Steam library I don’t recall a ton of updates to it, and certainly not many additions to the story or even more cars to drive. As far as I could tell it was a complete game, and it was willing to give as much as I was willing to look.

It’s now 2025. Most of the original Crossfader Crew has abandoned the city of Los Angeles for various reasons. I washed out of entertainment entirely after never formulating enough of a plan to get my foot in any kind of door. Our original editor-in-chief is a nascent restaurateur in New York City, I think. And while the specter of America’s own Years of Lead hangs over the country, WHEELS OF AURELIA is being delisted for not changing. And that doesn’t seem fair to me.

Later in the article published on Game Developer, Righa Riva goes on to label Apple’s delisting policy one of “obsoletion” that refuses to recognize games as an art form.

Creating anything is one of the most difficult things a human can do. A painting or a novel requires not simply materials but an inner sense of purpose and planning, not to mention determination to see its fruition. In addition to that, film and video games require the collective efforts of large groups of people all working together to achieve a common goal. And that’s to say nothing of the capricious whims of industry C-suite types and shareholders involved in larger endeavors, all tugging the ropes to make sure the numbers this year are bigger than those from last year.

Whether a piece of media has artistic merit is somewhat irrelevant; each and every one has purpose. Whether that purpose resonates with the consumer is what makes it art. And a good piece of art doesn’t need to change to stay relevant, it needs to change you.

That isn’t to say that it can’t change; director’s cuts can be released, second editions can be written and rewritten, a demo tape can be unearthed where you can hear the bassist laughing and it somehow sounds like the way your mom used to laugh when she really, genuinely laughed. But art doesn’t need to grow to be considered relevant or worthwhile, it’s enough that the viewer grows in relation to it.

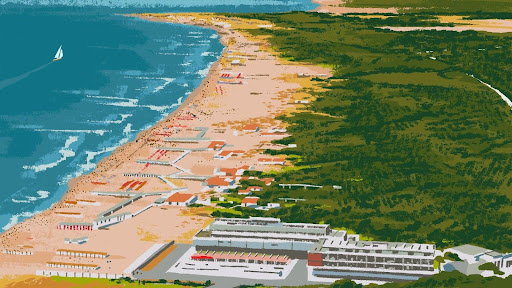

Playing WHEELS today, I’m reminded of what I really loved about it. The bouncing, crashing, soundtrack influenced by the progressive rock of the late-‘70s is so much fun, and the voices on the titular track sound like they’re having as much fun singing as I am listening. The art style of the character portraits is so distinct, and the images of the Italian cities that make up the Via Aurelia feel lifted straight from postcards of the era. Given my own situation, I sympathize more with Lella’s “anywhere but here” mentality while still recognizing its recklessness. It’s all like finding an old coat you used to wear all the time and realizing it still kind of fits you.

In the early days of the magazine we relied on a more binary “Recommend” or “Do Not Recommend” system, and I painfully gave WHEELS OF AURELIA a “Do Not Recommend,” simply because it lacked some of the mainstream signifiers of what games were at the time. I mentioned the game OXENFREE a ton, drawing similarities to each game’s narrative-forward design. And while I’d still draw that comparison, looking back on it I would rescind that final review and encourage people to play it. It’s not what you call a game? Who cares, fuck you, play it anyway. It’s trying to be Telltale? Telltale Games never owned a monopoly on narrative-focused, replayable games. Why don’t you explore how different people approach different concepts for Christ’s sake?

And while this article may have the trappings of navel-gazing obituary, WHEELS OF AURELIA isn’t disappearing. It’s still available on several platforms, including the Switch, Steam, and Epic Games Store. I just share the sentiments of other game journalists and Pietro Righa Riva that the corporate instinct to dispose of a game—or any piece of art—simply because it’s not hitting the arbitrary marks of some hack that thinks a chatbot is going to pioneer quantum physics is another damning indictment of the capitalistic obsession with obtaining more for the few to the detriment of the many.

Despite feeling ragged and hopeless deep in my soul, I’m grateful to the original Merry-Go-Rounders for giving me the chance to interact with each one of these pieces I’ve reviewed. They’ve all helped to shape the way I internalize and think about what I enjoy and why, even though sometimes it’s more of a curse than an ability. It emphasizes the simple fact that humans grow and humans develop. It’s foolish to limit access to something that can catalyze that development before it ever has the chance to.

Comments