HAMILTON may very well be a U.S. government psyop, but I’ve always been fond of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s IN THE HEIGHTS. In 2008, the show was a delight for sore eyes in a blindingly mayo theatre space, where its casting and music were revolutionary, the one and only time Miranda’s syrupy, clumsy lyricism felt sweet on the ears, where his earnestness felt crucial to the subversion of his show being put on the same stage as GUYS AND DOLLS. Unfortunately, Jon M. Chu’s film adaptation, fresh off the effusive praise for his billionaire apologia, CRAZY RICH ASIANS, is so distressingly cut from the modern veil of how we do this shit and have been doing this shit, existing completely differently in a 2021 cinematic space than it did on Obama-era Broadway. It’d be one thing if this was just a schmaltzy musical, where its biggest problems were the obnoxious framing (would these kids remotely care about Usnavi’s life story without any incentive?), overlong, and being corny right down to making a record-scratch joke. It’s an exhausting film, for both its 143-minute runtime and furthering implications for the future of Latino media, a landscape defined in a binary by narco shit or cooing and cawing at you like a lil baby (and then Iñárritu, Cuarón, or Del Toro getting a couple racks to be absolute psychos). I’m elated people are crying and cheering in their return to theaters to watch folks from the DR dance in the streets, but it’s difficult to deny how oppressive this falsified joy feels. There is so much doe-eyed, master-cucked “this is our home” messaging out there, and we’re fucking good on this assertion we never should’ve pleaded for in the first place. Where’s the thunderous furor of “this is our home?”

There’s an inherent goofiness to removing the stage and actually placing this baby-brained story of the inhabitants of Washington Heights in real Washington Heights in real streets with real people. Key to Broadway’s illusion (and its criticisms) is that you really aren’t meant to actually think of Washington Heights. Miranda’s original vision consisted of a couple of businesses, fire escapes, a dozen populated windows, and the Manhattan Bridge in the near distance, and this neat microcosm resembled as much a hideaway as it did a transplant into a whiter, opulent space. There are no roads, no subway entrances, no cars: no escape. The block is the only stake they got, and they don’t even own an inch of the property they reside in. The stage musical pondered what would happen if a miracle sum of capital was randomly introduced into the barrio. Look, it’s an elementary examination of Latino inheritance, but, hey, it’s there. Chu’s adaptation opts for pulling up your bootstraps.

It’s tough not to smile during IN THE HEIGHTS: it’s got rhythm, it’s got surface-level niche references to salsa musicians and regional cuisine, and it’s got everyone stuck in a perpetual beauty pageant smile. And you know what? It works. This is the first time I’ve ever seen pernil or pasteles in any motion picture. As it turns out, pointing at the screen to recognize a food you previously thought only you and your family ate produces a unity greater than any political rally. Food pandering is hands-down the best type of pandering. If you’re not smiling, you’re kind of killing the vibe, sweaty, why aren’t you relishing in this neatly packaged Latino joy, huh? Kind of sus, you a racist or something? Anthony Ramos and Leslie Grace deliver indelible Sesame Street celebrity guest performances, and Melissa Barrera’s got that acting program oomph, but her charmless performance is further sabotaged by trash vocal engineering. Her mouth is moving way too much for how static and classical her vocal performance registers, resulting in blatant lip-synching issues that, if you’re feeling charitable, could be attributed as an immersion-breaking technique to emphasize her desires to leave for the Fashion District, but there are also ways to make that arc not look like a post-production mixing error. The real Nueva York is defined by cracked smiles… Jubilance, but as a means of coping unity. Shit falls apart, but IN THE HEIGHTS’ cracks closer embody stagehand goofs than blips of lived-in experience.

On stage, IN THE HEIGHTS worked because Lin-Manuel Miranda looks like Homer Simpson. He might be someone’s cup of tea, but he’s not a traditional catch, and that is literally how I would describe 99% of people on planet Earth. He looked normal enough that you bought the central conceit of The Heights migrating to Broadway. Anthony Ramos? Hot! Melissa Barrera? Literally a model. The background actors have a familiar everyday ugliness to them that’s refreshing (and laughably out of place amidst the carefully manicured depiction of a Caribbean community), but it feels as if Usnavi and Nina and the rest of the gang are only the main characters because they’re the most objectively fuck-able in the community. It’s definitely not because their problems are the most interesting. And yet, it’s not a sexy film! IN THE HEIGHTS is decidedly a four-quadrant children’s film, going as far as directing Dascha Polanco to perform from her ass and then taking every opportunity to frame out her ass—it’s an odd thing to do to an actor! The red-hot caricatures just make for a better cartoon, I guess, a cheat code for POC joy.

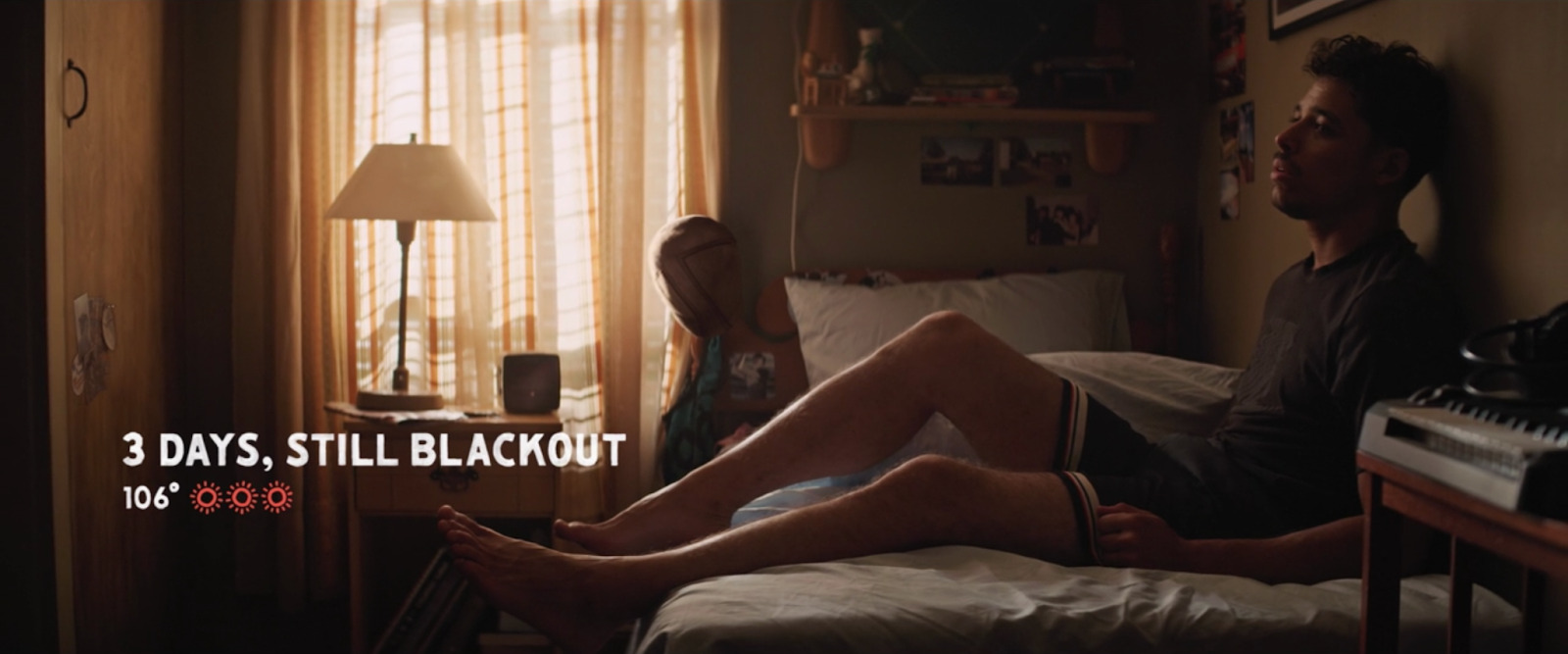

What is this joy compensating for? I suppose in answering that you’d just be remaking DO THE RIGHT THING, but, hey, there are worse movies to mimic than the greatest American film. Spike Lee’s opus famously centers on a civil meltdown amid a power grid blackout, and it has the colors and fatigue to boot, which makes Chu’s choice of a cool color palette and not a bead of sweat in sight so much more baffling. The hottest week in The Heights is portrayed in muggy overcast. After a death that shakes the entire block, we’re supposed to note a temporal shift in the community, but there’s such little visual impact because the whole film has already been cast in a grey shade. There’s no red-hot anger when the aforementioned blackout (which of course has only afflicted The Heights) murders the matriarch of a community. It’s all “follow your dreams” and “chase your sueñito,” but Usnavi and co. maintain a passivity to the onslaught of gentrification, rent hikes, and nationalist legislation. Just keep your head in the mud and your sueñito will probably, kinda, maybe come true! Miranda’s romantic notion that Latinos are the only ones willing to do the work no one else wants to do is Liberal poison: our lone specialty is not endurance.

Speaking of endurance, let me remind you: the film cuts out several major characters and songs, and yet it’s still 143 minutes long. IN THE HEIGHTS is likely two-and-a-half hours because every number is followed by a dialogue exchange reiterating the content of the song just sung. How can something so distinctly Dominican, so Puerto Rican, be this slow? How did you fundamentally misunderstand the dynamic of these cultures this badly? The rat-a-tat rhythm blows its load in the exciting intro, gradually turning to a formula of centering on two characters then awkwardly cutting to random company dancers two-stepping at a remove from the actual center of the song before a brief spritz of group dance. So many of the musical bits feel tacked together with high school-level choreography and a camera that feels obligated to show the dancers rather than give in to the potential, squandered vivacity. “96,000” is a complete mess, with Busby Berkeley-adjacent crowds splashing in the water as every principle gestures neatly in their own separate frames as if to sell you an AT&T family plan. It’s more than a commercial aesthetic: IN THE HEIGHTS is insistent on selling you on something. Mexicans in your country? An extra month to your HBO Max subscription? Who can concretely say, but I feel like I’ve been fed a Clinton-funded subliminal. And now, a PSA from Merry-Go-Round Magazine…

SPANGLISH 101: A COURSE FOR WHITE PEOPLE:

- Spanglish does exist, but never to say a word in Spanish and then immediately translate it in English. A phrase like “It’s your suenito, your little dream,” is only uttered in Lin-Manuel Miranda lyrics, Dora the Explorer, or self-conscious interviews by white-Latino film executives wanting to prove they know enough of the language to ethically exploit the Hispanic consumer demographic.

- As is the result of colonialism, there is a whole lot of the English language embedded in foreign languages, but the slight advantage of that is that there is so little foreign influence on Anglo language. You can translate most English slang 1:1 to Spanish, but Spanish has definable phrases that also carry the exact intended intonation. “¿Mande?” will never mean anything else but “¿Mande?” and there is no word or phrase in the English language that can convey its meaning as succinctly or exactly. If anything, Spanglish is utilized to combat the limitations of English, but it’s still both uncommon and largely unnecessary.

- While Spanglish does exist, 99% of the time you will be in the presence of Latinos who will simply speak entirely in unbroken Spanish, regardless if in the presence of primarily English speakers. Can’t understand what they’re saying? Good. That is likely by design, gringo.

As a work of adaptation, Quiara Alegría Hudes completely slaughters her own source material, excising the frictions of colorism and capitalism to produce a streamlined product unwittingly engaging in the throes of each. In the stage version, Abuelita Claudia’s showstopping “Paciencia y Fe” number is motivated by the song’s final reveal: in secret, she’s won the $96,000 lottery that’s got the whole town talking. The song, a pained recollection of a mid-century immigrant experience, is a gracious celebration of her steadfast persistence, but also completely tragic. None of her work got her to this point of sudden success. She won a literal lottery in a country that was not designed to offer her the dignity of financial security or an independent sense of self. And then she dies of state-mandated stress and heat before getting to buy a single loaf of bread. In the film, the motivating factor is that… She’s chosen to die?

What?

In the original work, Usnavi is motivated to stay in The Heights when a graffiti’d mural of Claudia is painted on his store. It’s in reshaping what he once considered vandalism on a building he’d once considered a trap that sways his decision to choose Nueva York as his true home. Of course, Miranda never had his teeth out for the policing that deemed graffiti as vandalism or for bodega landlords who make life a daily strife, but there’s at least a fraction of a hint of a speck of an inference that these factors are at play. Hudes cuts out so much of the meatier conflict that Usnavi decides to stay in New York for the pussy. Nina doesn’t drop out of Stanford because of the systemic limitations of a college education in America, it’s because she’s mistaken for a waitress at a gala. Her relationship with Benny is no longer marred by her father’s racism; now, it’s…. Actually, there’s literally nothing driving it. The film has their romance remain a centerpiece, despite expelling all the drama that originally made their romance a centerpiece. It’s some of the worst adaptation I’ve ever seen.

The discourse surrounding the film’s lack of Afro-Latino focus about a slice of Manhattan heavily populated by Black denizens is… Yeah, that’s an issue. It’s normally not an issue for me. This critical concept of, say, oh Martin Scorsese only making movies about old white men doing old white men things, and then leaving that baby’s-first-social-critique at that instead of analyzing the very state of patriarchal American decay that Marty hyper-fixates on in every film is one of the more bludgeoning blows to dynamic, modern film discussion. IN THE HEIGHTS is not a Scorsese picture, nor does it have much of a unique perspective to contextually support its beige casting. “Carnaval Del Barrio” sees the major ethnicities of the block represent their native countries in a rapturous, flag-flying climax, and while it’s a fun Disney parade, it’s also the moment it sinks in how poorly Chu and Miranda have painted the reality they were seeking to honor, relying on white casting directors aiming for the right blend of coffee and cream and silky caramel skin tones to capture the authenticity of The Heights. Chu’s IN THE HEIGHTS is aiming to be a census, and so many are so blatantly unrepresented. It’s one of the fairest criticisms you could levy at the film.

For a few more years, until it pulls a MAMMA MIA! and randomly becomes the most popular film ever made, Jon M. Chu’s IN THE HEIGHTS will be seen as a commercial flop amidst an aggressive marketing campaign and a vocal critical boost. In some regards, the underperformance is surprising! If you hadn’t seen advertising for the film, a glossy Warner Brothers adaptation of HAMILTON’s own Lin-Manuel Miranda’s 2008 broadway debut, then you truly were a die-hard quarantined mole-person. In most other regards, of course this movie didn’t become a smash blockbuster hit. As it turns out, “It is your moral imperative as a Latino and/or white Liberal to see IN THE HEIGHTS,” coupled with “See IN THE HEIGHTS in theaters, lest you want to see every theater die, and it will all be because of you, also by the way, you can watch this for significantly cheaper at home” is not a great way to market a movie in a country antsy from a year-and-a-half of administrative mandates. Not only that, but the argument that this performative ebullience is what’s most needed after a year of trauma primarily inflicted on Latinos is completely deranged considering 2020 was nothing but saccharine showboating. IN THE HEIGHTS is about as helpful as clanging some pots and pans for exhausted, embittered, and eternally altered medical professionals emerging from a viral death pit day after day. Caught under the ire of those who disdain him and the impatiently hungry masses clamoring for a HAMILTON follow-up and nothing less, Miranda finds himself at a plateau moving forward. Considering he’s the standing king of the theatre kids, we’ll likely be forced to hear about every little step.

Comments