“I’d give up my firstborn son for a new, good ZOO TYCOON game.”

This is a phrase I think I say at least once a week. Over time other permutations have arisen:

“I’d give up 30 years of my life for a new ZOO TYCOON.”

“I’d literally kill for more ZOO TYCOON. Actual, literal murder.”

“I would drop out of school, shave my head, and give up on life if it meant I could spend even one hour playing ZOO TYCOON in any capacity.”

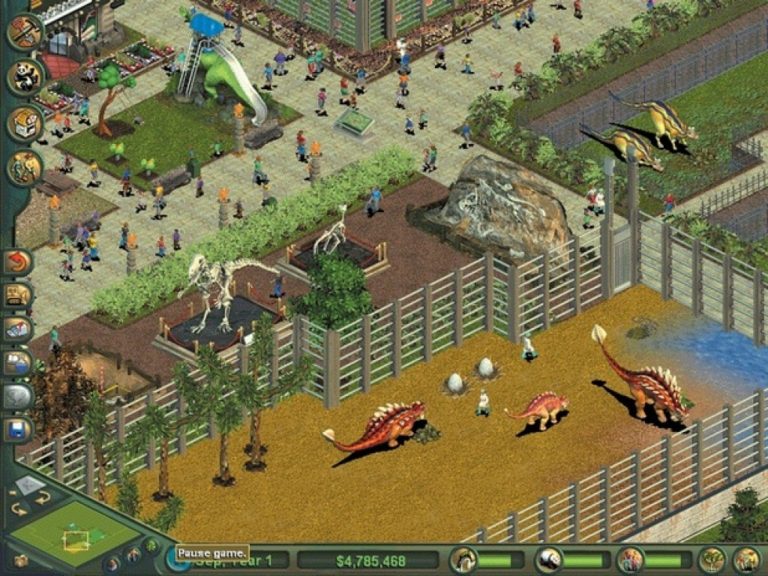

Now I don’t just want any ZOO TYCOON. I want good ZOO TYCOON. The classic, plain-as-vanilla-ice-cream, capitalist-to-a-fault ZOO TYCOON. ZOO TYCOON that’s asymmetrical, with a locked-down camera and an art style that isn’t trying hard to be realistic, but rather, evocative. ZOO TYCOON like the first ZOO TYCOON and its excellent expansions. ZOO TYCOON you take home to the family. The kind of ZOO TYCOON you marry and have three kids with.

This ZOO TYCOON, the stuff of dreams all too real, burst onto the PC gaming scene in October of 2001. It was more or less a direct response to the ridiculous success Hasbro Interactive experienced after publishing ROLLERCOASTER TYCOON, a business management simulation about balancing a rollercoaster’s ability to induce vomiting with the cost of popcorn. ZOO TYCOON takes that formula and applies it to the actual lives of animals. Naturally, it was a match made in heaven.

Not a zoo, but rather a machine that turns animal life into cold, hard currency

Developed by Blue Fang Games and published by Microsoft Studios, ZOO TYCOON perfectly fuses the OCD-indulging tendencies of park design and path placement with the more erratic and exciting mood monitoring elements popularized by THE SIMS. These, combined with a deliciously oblivious wrapper of earning profit at all costs, creates a game that feels new each time you play it, while being comfortably predictable.

These essential feelings are expressed in the game through three distinct modes and the basic gameplay loop. At its core, ZOO TYCOON is a game about spending money and waiting to spend money. You spend money, placing objects in the park, purchasing animals, hiring zookeepers and other workers, and then you wait, planning on how you’ll spend money next. There’s always another animal to add to your zoo, another beautiful enclosure to construct, and another money-making food vendor to install. But funds are limited to the tickets and concessions you sell and the donations you receive, so the rest of the time you cross your fingers and pray you don’t go into the red while watching animals react and guests freak out when a lion roars. To the primary audience, this focus on capitalism in the purest sense seems harmless. Money, when it comes down to it, is just as meaningless as points. Perhaps the perspective of time warps things, but in comparison to other “management sims,” where the means of acquiring capital are more abstracted, ZOO TYCOON takes on a layer of maliciousness.

Zoos, while being for-profit enterprises, are ultimately about conservation and ecology. The money-making ability of the animals is only a concern as far as it continues to guarantee their safety and well-being. Their experience, whether happiness or pain, is at least never hard to connect to or understand. In ZOO TYCOON, animals can’t convey emotion. Or at least, no emotion that can’t be described using an emoticon. It makes the process of making the animals suffer an easier pill to swallow. Ultimately it’s just the money that matters. The money is how I build the next thing. It’s my points. It’s THE point.

Smiley faces don’t exactly capture the depth or breadth of the gazelle experience

Normally this kind of blatant capitalism wouldn’t bother me. Obviously ZOO TYCOON isn’t trying to make a political statement as a game (except that maybe protecting animals is “good thing”), but the realization that this game, and many like it, are dependent on a simplistic but incredibly prevalent ecopolitical philosophy is important. What does it say about management sims that the only way they work is by forgetting the small stuff (human or animal life) and focusing on the “value” of things? What would a game look like that adopted a different tact or a different philosophy? Unfortunately, other than through hypotheticals, these questions must remain unanswered. Partially because of the health and viability of this subgenre of games itself.

In some ways, ZOO TYCOON arriving on the scene in 2001 symbolized the peak of the business management sim craze. There were sequels and spinoffs (ZOO TYCOON: DINOSAUR DIGS, ZOO TYCOON: MARINE MANIA and ZOO TYCOON 2), but the genre never again achieved the highs it had in the early 2000s. Most of this is due to the shift from PC gaming to home consoles. A shift perhaps best exemplified with the release of a new ZOO TYCOON in 2013 exclusively for Xbox One and Xbox 360. This console version has its own problems, from mechanical issues in regards to pathing and park customization, to a general lack of content. Most PC games reliant on mouse input that make the jump to consoles arrive in stripped down or completely unrecognizable forms, and this game was no different. But that aside, the console version of ZOO TYCOON was at least a new way to play ZOO TYCOON. The real problem of writing about ZOO TYCOON as a cultural relic is that there is no easy way to play the original game as it was intended.

Operating systems update and old games shouldn’t necessarily be expected to keep up (especially games old enough to not have online multiplayer), but in order for me to play ZOO TYCOON today, I either have to emulate a Windows PC circa Windows Vista, purchase an old Macbook and a disc copy of the game, or travel back in time. None of these are particularly viable or easy options. This fact is especially ironic, given the subject matter of the game itself: preserving animal life for the education and enjoyment of future generations. Game preservation is an aspect of the culture that is not often thought about because it is not often needed. Most online stores (namely Steam and GOG) either have the old games playable, or, in more recent developments, a remastered version of the game. But when you run into instances of gaps in the library like this, preservation feels especially lacking. The logic of zoos in ZOO TYCOON is that having something interesting and displaying it in an engaging way is the best method to earn money. One would think that games could work in the same way. Reality has yet to bare this theory out.

If money can keep a dinosaur alive, why not a game series?

ZOO TYCOON occupies a space at the intersection of legitimately good, fun to play, well made, and horribly inaccessible. That’s the perfect fuel for nostalgia. That’s the cause of the addiction-like itch that is playing in the back of my head as I’ve been writing this article. I’ve researched buying laptops for this game. I’ve considered secretly installing it on a library computer. It has become an obsession. This is because of what it is, but also because of what it’s not. It has no story, complex mechanics, or even large amounts of customizability. It is, when it comes down to it, a copy of an equally, if not more, popular game series. But what it does it does well. Against your better judgement, you put a T-Rex and a Lion in the same cage. They kill each other, but they sure got a lot of people to buy tickets. Scenarios like these are the bread and butter of the series, and why my first born son already belongs to Blue Fang Games.

He would have been named Jeremy, if you were wondering.

ZOO TYCOON (and its expansions) are playable on Windows and MacOS (10.9 and earlier)

Comments