This article previously appeared on Crossfader

Director: Robin Campillo

Genre: Drama

Year: 2017

There’s never an excess of LGBT films available to the public, but that doesn’t mean that outings of this subset can’t be trite or derivative. We’ve explored Caucasian narratives from almost every single angle at this point, but 120BPM postulates itself as somewhat of an essential biopic: a study of an activist movement and all its inner workings. It’s set up in many ways in the ilk of Soderbergh’s CHE or Assayas’s CARLOS, briskly jumping between plotting, protesting, and all the ensuing fallout—particularly within the inner workings of the group. People disagree, make love, fight, and make up. It’s an emotional whirlwind for its characters, but I can’t help shake the feeling that it’s never quite as turbulent for the viewer.

Director Robin Campillo is assured in his neo-realist direction and makes it clear that his primary focus is positing triviality. Is all of this worth it? Should these men and women, at their weakest point in their life, endure the stamina rollercoaster of constant protesting and organizing? It’s certainly worth noting that hardly any line of dialogue in 120BPM doesn’t refer right back to the HIV crisis. It’s a tragedy they simply can’t get out of their heads, making it borderline impossible to enjoy their last days alive. Not even the beaches they daydream of vacationing at deliver, covered in thick cement blocks, an eyesore that detracts from its environmental beauty. Its characters’ lives are mired in disappointment.

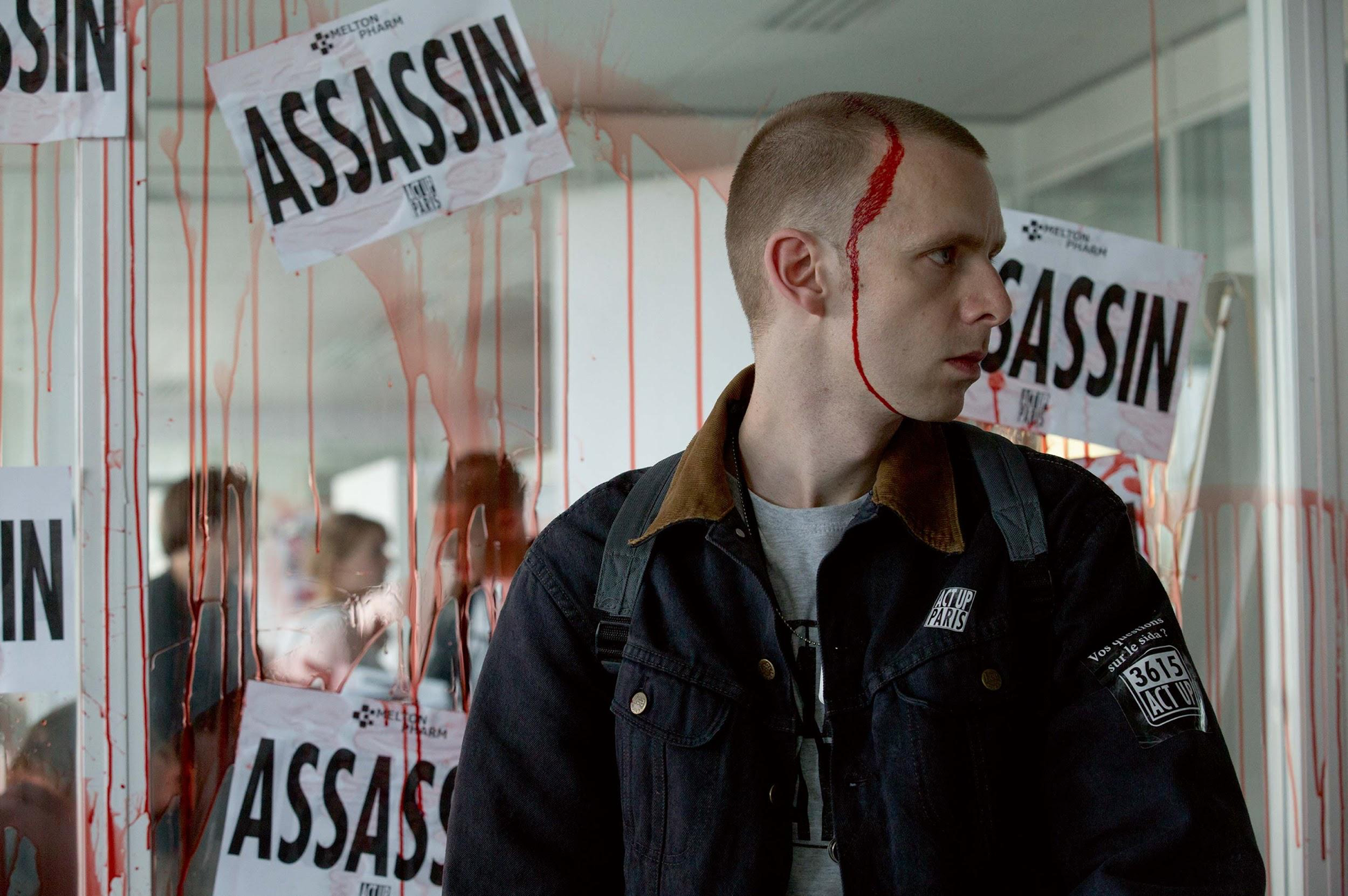

JUST IN: New ASSASSIN’S CREED set in ’80s Paris gay scene

Campillo clearly knows what he’s trying to say here, and as a formalist, he’s quite adept. Scenes cued to music are phenomenal; in fact, they’re so well done that the overall handheld quality of the rest of the film almost registers as a little phoned-in. Numerous squabbles are showstopping in their intensity, and the film’s very first meeting scene is wonderfully staged. The immersion is magnetic in its pull, so it’s a shame that almost every scene of Campillo’s 135-minute epic is five minutes too long. What should be a clean, lean, 100-minute experience is made a little too languorous for its own good, and Campillo’s inability to spend his extra 35 minutes making me really understand and love all of these characters doesn’t bode well for the final product.

Frankly, it’s a bit of a cop out to only make me care about someone because they are HIV positive (or activists for an HIV awareness group). I should love these characters, but as it stands, I root for them because there is absolutely nobody else in the picture. In a closing sequence involving each major character walking into an apartment one by one, I felt little connection to each of their personal stories. It’s a sequence that begs to be as engaging as TONI ERDMANN‘s final apartment scene, but never quite hits that note. Sure, one involves a nudist party and the other is a wake, but my sympathy for these characters should be the same regardless. I can’t say 120BPM ever fails at anything it sets out to do, but I can say that AMOUR covered mercy killing more gracefully, and NO! covered the inner workings of protest groups with a greater punch.

Pictured: an ensemble cast I spent over two hours with and yet fail to remember a single name

With all that said, it’s hard to outright criticize 120BPM. Hollywood pumps out far less engaging (or essential) true story nonsense each year. It’s a film that will certainly find a following in the cinephile LGBT scene, but its greatest setback is that it’s almost too elitist, a film that screams that is was made for a Cannes audience. When championing something as hot-button as gay rights in the 21st century, accessibility should always be worthy of consideration, and I’d be hard pressed to say that anybody who isn’t an ardent cinephile will even consider seeing 120BPM. In that way, it does remind me of 2016’s I, DANIEL BLAKE, a film that suffered much the same fate. In a post-MOONLIGHT, post-CAROL film scene, I’d wager that LGBT films shouldn’t skate by on the novelty of their milieu alone. Sure, 120BPM does a fantastic job at de-stigmatizing the photography of anal sex, but so did OTHER PEOPLE (a film that boasted much broader appeal). As a work of dramatic storytelling, Campillo’s film is never poor, but it doesn’t grab you by the collar the way it ought to, indulging just a little too much in each of its set pieces and failing to bring anything new to the table.

Verdict: Do Not Recommend

Comments