When BASTION came out in 2011, my 16 year-old mind was blown. Supergiant Games’ debut was a formative game for me, one of the first I played that I found more engrossing than its AAA contemporaries. The game oozed personality through its colorful art and stunning music and voice work, setting the stage for what would become Supergiant’s trademark style. Nearly a decade later, Supergiant has created what might just be their masterpiece.

HADES is so good it makes me love BASTION less. Supergiant’s last two titles, TRANSISTOR and PYRE, were both divisive but daring genre-mashups. TRANSISTOR applied strategic turn-based elements to the 2D action game, while PYRE took the visual novel and fused it with NBA JAM. Unlike these titles, HADES neatly fits into a popular genre; the roguelike. This type of game is typically reserved for “serious gamers” but HADES has found itself a broader audience by shifting the goalposts of what to expect from a combat-heavy, procedurally generated, run-based game.

Initially, it is the game’s emphasis on storytelling that sets HADES apart. In the same way that the game is a unique take on a familiar genre, its story and characters are clever modernizations of Greek mythology. It’s not just how HADES reinterprets and expands upon age-old myths like Orpheus and Euridyce that makes this special, but the way each unfolding event feels catered to your pace. The premise of the game justifies the gameplay loop and allows the characters room to grow organically. Even if you aren’t making progress in the chambers of Hell, you are still getting new dialogue and seeing character arcs progress—30 hours in and I still haven’t seen a single piece of dialogue repeated.

HADES gradually builds out characters and side stories just as readily as it does mechanics

But saying “HADES is the first roguelike with a story” is kind of missing the point. Despite the fact that it is a skill-based game, and a pretty tough one at that, the goal of HADES is not to get good. HADES is the most successful attempt at shifting the focus of the roguelike away from mastery and towards a more holistic, thematic approach. Take the more traditional roguelikes for example. The goal of SPELUNKY and THE BINDING OF ISAAC is first to beat the final boss, then to beat the “actual” final boss, and so on until you either give up or make the game bend to your will. Whenever you hit a ceiling, it fades like an illusory wall to reveal an even higher ceiling. Dedicated players find this endlessly rewarding. But these games offer little assistance to help you improve, especially early on. Most players fall off the opening hours of these titles extremely hard.

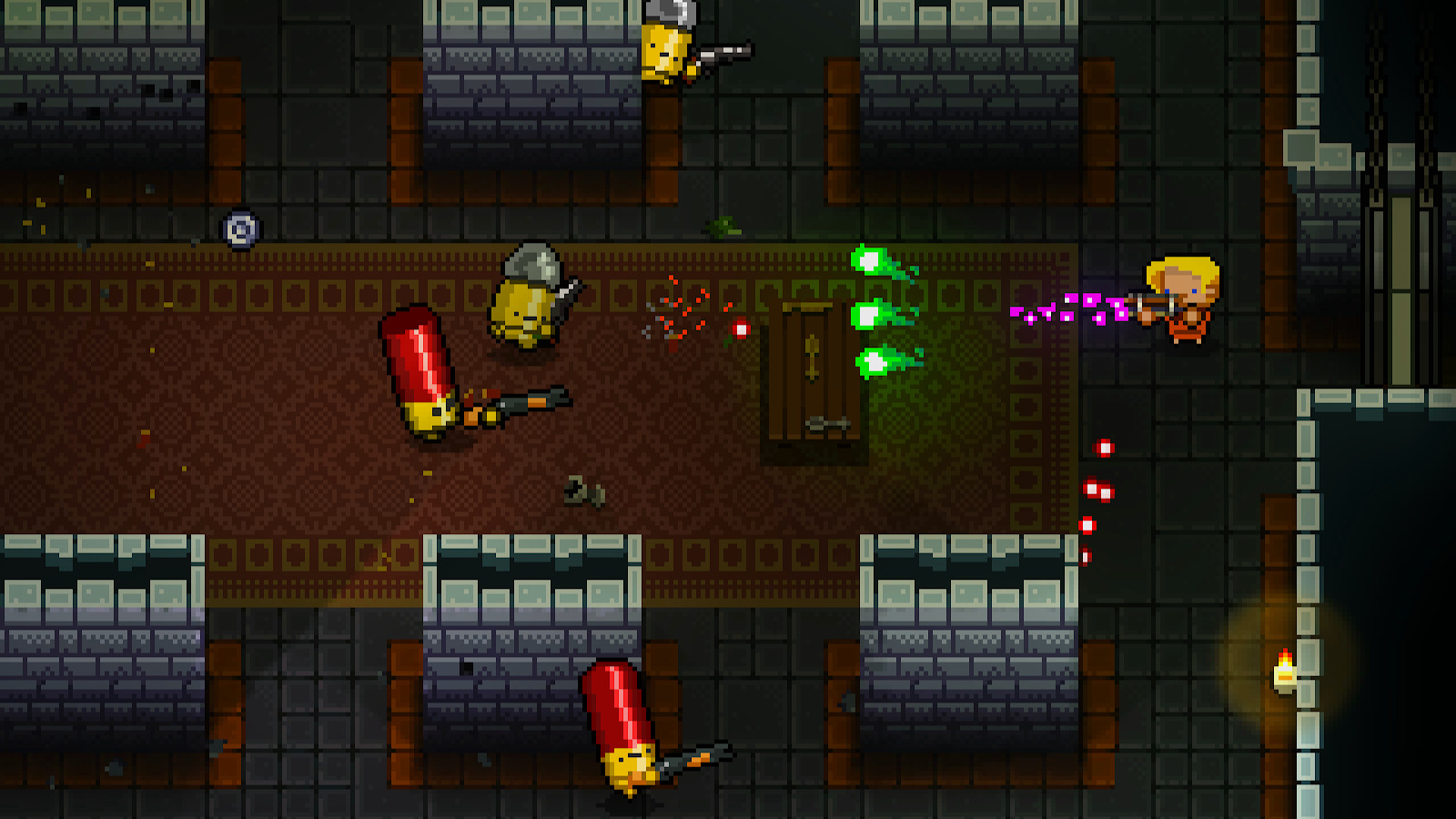

Technically HADES is a “rogue-lite,” but I believe it defies the genre entirely. By comparison, roguelites like ROGUE LEGACY and ENTER THE GUNGEON give more in the way of incremental progression options to ease the harsh learning curve the genre is known for. They make concessions that usually consist of persistent upgrades, but most roguelites are still fundamentally about mastery. These are design choices implemented to make the genre easier for new players, but in both these examples and many more the end goal is still mastery. The term itself is a tad condescending in origin. “Lite” evokes shitty low calorie beverages that are better for you, but they aren’t the real deal. It is a term that implies a compromised product.

Seconds before being overwhelmed in ENTER THE GUNGEON

HADES is anything but compromised. More so than any roguelike, it puts the fun factor in the players’ hands. The different upgrade materials earned may be overwhelming at first, but they make it so each early game escape attempt is rewarding. The variety comes from a tight selection of weapons, customizable abilities, and ever-growing upgrade options that uncover HADES’ onion-like depth. After about 20 hours, you start to recognize rooms and enemy patterns and the feeling of randomness starts to fade. In the late-game, The Pact of Punishment even lets players choose how they want to increase the difficulty and to what degree. This ingenious little piece of design lets players continue peeling back the layers of combat or alternatively, if they are in it solely for the story, let them continue to stomp the final boss with ever-decreasing resistance. Neither option feels like the right or wrong way to see the endgame.

Boons and other persistent upgrades constantly push the game forward

HADES is challenging to a degree, but past a certain point the persistent upgrades can make the game quite trivial—if this isn’t your experience, you can always turn on God Mode, a clever twist on an “easy” mode that turns down the difficulty with each death. You will still be able to see the main story and continue diving into the character relationship dynamics that define the game. Beyond that, how difficult you want the game to be and in what way it’s difficult is left entirely up to the player. It becomes increasingly clear that HADES doesn’t want to punish you. The game is about failure, but it wants you to understand Zagreus’ pain and frustration, not to feel it yourself. You, as Zag, are progressing through the story regardless of your skill. The narrative flows differently from player to player, but for each it feels like a linear progression playing out naturally over the course of however many hours it takes to see credits.

We can see how a lot of these ideas began to percolate in Supergiant’s previous game PYRE. In fact, the procedural storytelling in PYRE is less like a magic-trick than HADES, and thus a bit easier to analyze what is actually going on. Yet, there is no failstate. That is a stated intention from the game’s creators. You must lead a diverse crew of this world’s exiled inhabitants through a series of purgatorial sports competitions. At the end of each tournament, the winner gets to send someone back home. This often means giving away one of your best players, but you do it because the game makes you care about them as a character. The writing is so strong that I lost multiple games on purpose. The game is genuinely challenging enough where I lost others despite trying my darndest.

PYRE sets up a fantasy basketball tournament where failure isn’t the end

“Players are very conditioned to expect to win and they inherently don’t naturally feel good about losing,” Supergiant writer and designer Greg Kasavin said in a Gamasutra interview, “so the game itself bears a certain burden of making players understand that those types of outcomes, in the context of PYRE, are actually okay.”

Supergiant doesn’t make games where players can’t fail, they make games where players will inevitably fail as a reminder that failure is a crucial part of life. And that’s what HADES is about; making failure feel natural in the ebb and flow of existence. This feels like a big statement, but learning from failure is inherent to all roguelikes, HADES just embraces it as a narrative theme and a design philosophy.

GRIFTLANDS cards work outside of combat too

Of course, HADES isn’t the only roguelike pushing the genre out of its old patterns. Klei Entertainment’s early access deck-building roguelike GRIFTLANDS shys away from combat, instead focusing on decision making and dynamic storytelling. The game uses card battling mechanics ala SLAY THE SPIRE, but each encounter can require they be used for combat, negotiation, or a mix of both. Each of these games adds characters and story to a genre usually devoid of this element, but what’s impressive is how the two could not be more different. GRIFTLANDS is the slow methodical counterpart to HADES’ frenetic action.

The blossoming of the shooter required the death of the DOOM clone and the HALO killer. The adventure game hit the mainstream when creators stopped adhering to the point-and-click format that used to be in the very name of the genre and studios like Telltale focused on choice-driven storytelling. The procedurally generated run-based game is still in its infancy. Games like HADES and GRIFTLANDS are breaking down the walls of the roguelite and creating new possibilities for procedural storytelling. They pave the way for a future where the roguelike is no longer just a genre exclusive to the hardcore gamer.

Comments