Ryan Martin Brown is a bit of a jack of all trades in the independent Brooklyn film scene, but he would rather talk about the work of his collaborators and friends. When discussing his filmmaking experiences, Brown says “we” as much as “I.” Previously, he’s directed a handful of shorts, mostly peering into the lives of directionless 20-somethings bumming around New York—NORA AT THE BEACH, in particular, is a surreally great one to watch if you’re the kind of girl who can’t figure out how to just “go with the flow,” or if you’ve ever dated a girl like that.

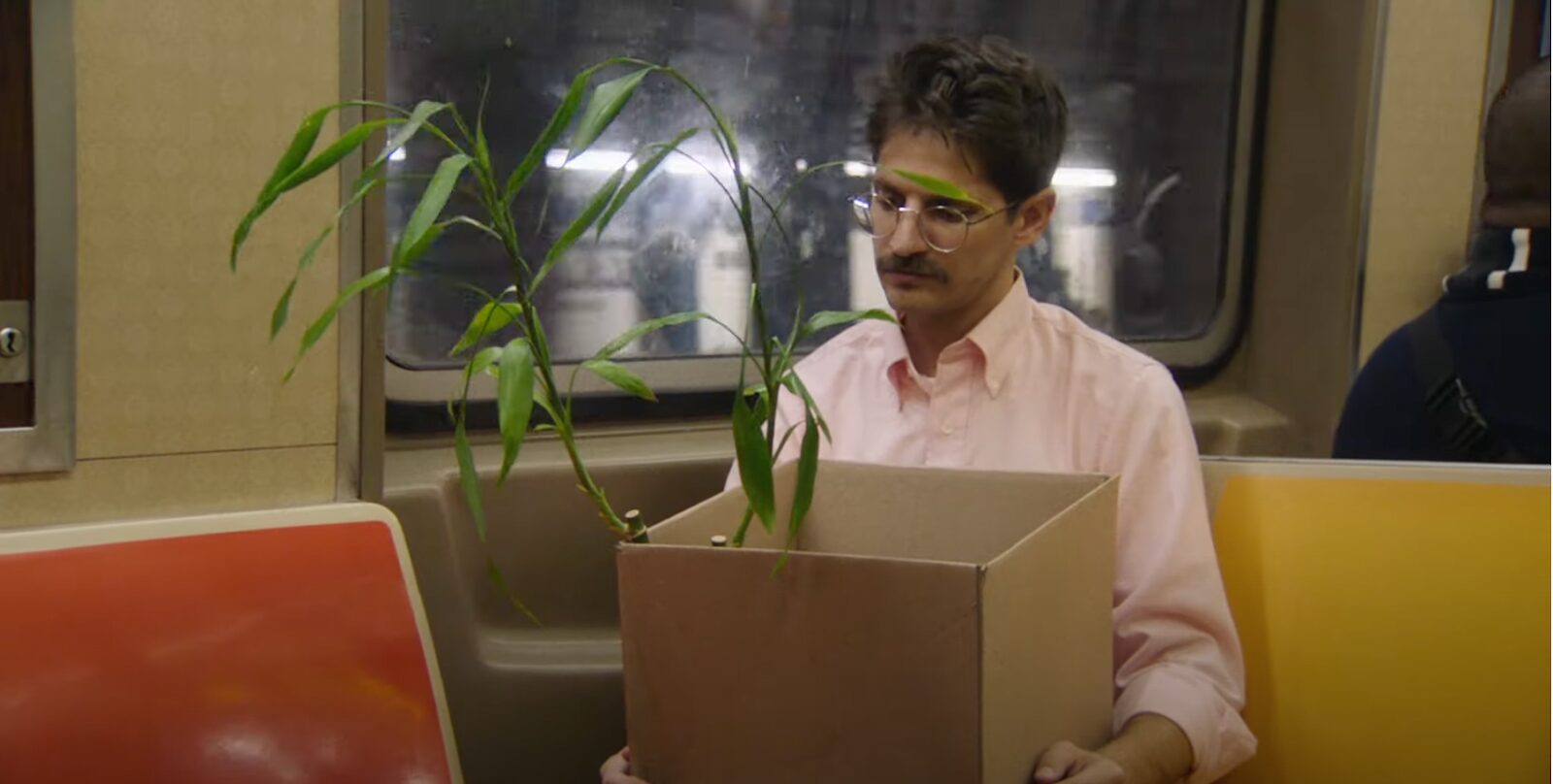

Brown’s debut feature, FREE TIME, is an uproariously funny study into the mind of Drew (Colin Burgess), who is, yes, yet another aspiring Brooklyn musician who despises his day job. One day, Drew abruptly quits his data entry job, then immediately regrets it once he realizes his vague ambitions are exactly that: vague. His prospects are few, and the clock to pay rent starts ticking (not that he would ever admit these things to anyone, including himself). Drew rages against the machine, and then cries “discrimination” when the door back into the machine remains shut. His roommate Rajat (Rajat Suresh) and Rajat’s partner Kim (Holmes) aren’t so interested in Drew’s pity party. They just want him to get out of the apartment.

I caught Brown on the phone earlier in March to discuss building a supportive filmmaking community, writing during lockdown, what makes a great comedic performance, and the spiritual importance of being honest with yourself.

[This interview has been edited for length and clarity]

Ryan Martin Brown: You’re in Brooklyn too, right?

I am, I’m in Lefferts Gardens right now. Where are you?

RMB: I’m in Crown Heights.

I figured from the shooting locations of your film.

RMB: Yeah, there’s a lot of Crown Heights.

In addition to making your own short films, you worked with Lynne Ramsey as an actor; you’ve worn a lot of hats—you’re an editor, you produced last year’s sleeper indie hit YELLING FIRE IN AN EMPTY THEATER, which is also about aimless New Yorkers, and you co-founded a production collective called 5th Floor. Did you always know you wanted to write and direct your own films growing up in Florida, or is that something you came to while you were working in the industry?

RMB: I did always want to write and direct. I went to film school in Tallahassee; the way that program was set up is that you would just do every position on different sets all summer. So, you would make your movie, and then you would do every other position on everyone else’s movie for the rest of the year. It’s a small school and you always felt a little bit like underdogs, maybe because you’re in Tallahassee in the middle of nowhere kind of away from everything.

So, it created this mentality, in a great way, that to make movies and to have maybe a creative life with other people—because all of these projects you can’t do alone, and they require so many other people—you do wear multiple hats, and people will wear multiple hats for you when you have something that you think is worth getting people behind. So it’s always just been what my life of making things has looked like. It’s always kind of been… I was about to say a merry-go-round—

*laughs*

But it is always like a little bit of a merry-go-round in terms of popping in and out of different people’s projects, and that takes the pressure off of it always having to be about your thing. It’s really restorative to get excited about someone else’s project, to get lost in that.

I attended a really similar program in Virginia. I worked on other people’s short films and they worked on mine. That’s where I realized I would rather write about other people’s movies than make my own. Did you meet a lot of your collaborators in this program?

RMB: I did. A lot of the programs that aren’t NYU or USC—the big ones—operate like that. It’s an awesome way to learn to make stuff. I did meet 70% of the people who worked on the movie, if not directly friends, from my time [in Tallahassee]. Like Mackenzie Jamieson, one of the producers on the film, was a bit younger, so we weren’t at FSU at the same time, so we met up here after, but it was a shared community. So, directly and indirectly, yeah, it totally all leads back to that initial community down there.

You wrote the screenplay with Colin Burgess in mind. How did you guys meet and what was it like working with him on set?

RMB: Colin was one of those faces that you would see on NoBudge all the time. If we didn’t know people from Florida, the only other way we got to know people was through NoBudge. Whether that’s seeing people on your computer screen when you’re at home watching other people’s work, or going to the live screenings at the Nitehawk. So we were aware of Colin through that. And then when Justin Zuckerman was making YELLING FIRE he gave him a role. [Colin] was so funny and so great to work with, and he has such a distinct comedic persona that, later on, when I was thinking about this movie, it was very easy to pop him into what that idea was.

He was amazing to work with. He’s obviously been doing stand-up for such a long time, but he really is an actor in the truest sense. The schedule of the movie was so insane, we were moving so fast I leaned on him incredibly heavily to be, like, “Okay, this is the scene, and this is the new actor who is joining us today. In five minutes, we need to figure out what the angle on this is, how we are going to make this feel alive and work.” He was the best collaborator in the sense that he was so great at finding a way into the scene that was entertaining to him. That helped because we had this wide ensemble of people who had to show up for one day, he was instrumental to creating an environment that allowed the performers to hop in and have fun. He was a great leader in that way.

Was there a lot of improvising, or was it all in the script that you wrote for him?

RMB: Colin was, but we were so tight that we couldn’t go crazy. We were making things up that everybody would definitely tweak. It could be as simple as Colin taking the word temperature and he would keep saying “temp.” He decided this character is the kind of guy who would say “temp.” Choices like that are littered throughout the movie. It’s not improvisation in—I know you saw DAD AND STEP-DAD—the sense that you’re pulling it out of nowhere, but they spent a lot of time tinkering on that line-by-line basis.

Did you write the role of Kim for Holmes as well? They had such a way of taking a really simple scene and making it so funny. When Kim is asking Drew to get toilet paper, I was like “Why am I laughing so hard?” Their confidence is insane.

RMB: I will say, the end of that scene is probably more true improvisation on their part. That scene was supposed to end before that interaction. Holmes is just like Colin in the sense that they have an amazing ability—and confidence is a great word—to find where in the scene they want to enter. It really comes down to being able to entertain yourself. If you can find something you think is funny in a scene, it transfers so well to an audience. They’re both exceptionally gifted at being able to do that.

I did write the role of Kim with Holmes in mind, Holmes went to FSU as well. Holmes, Rajat, and Colin, they all knew each other from the internet, they all had mutual friends but had never met. So, to get to bring them all together and set up scenes was the most fun part of doing the movie in general.

Shooting on the streets of New York in 10 days is pretty stressful, so having collaborators like that is kind of essential.

RMB: Completely. And that goes for pretty much everything on the movie. Going into it, we were just coming out of a year of lockdown, and something had happened in my brain where I’d gotten a little naïve, and I’d forgotten everything I’d ever learned about what making a movie means. I had kind of convinced myself that we could do this thing in 10 days. We were kind of like, “Oh, this is just a little thing we’re doing, it’s not like a big movie.”

Of course, it was a lot to take on, and if it wasn’t for how talented all the performers are, how talented everybody behind the camera was… There were a million reasons why this probably should have collapsed somewhere in the middle. It’s really a testament to the whole team that it managed to hold together.

Some part of you remembered how to make a movie. You made a feature!

RMB: Well that is true… But the naïveté is more [the scope.] To use it as an example, DAD AND STEP-DAD is more the movie you should try to make in less than two weeks. It’s a small cast, it’s one location. This movie, in terms of the scope, and how many people are in it, and how we wanted to shoot it, like, if you were being smart about how to make a movie, we were doing everything wrong in terms of what would have set us up for success.

I was wondering about the journey from the conception of the script to watching it with an audience. Have you seen it with an audience yet? What was that like?

RMB: I was trying to write a different movie for Jessie Pinnick, who is in the film in that center scene. I was writing this other script for two years, and it was never quite making sense. It was thematically similar to this movie in some ways. I kept getting frustrated during COVID, during the first few months of lockdown. I was like “You know what, I’m going to write the most direct version of what this theme is.” Which is this guy is stuck somewhere, and he wants to get out, and he’s gonna realize that just because he gets out, that doesn’t necessarily mean that he’s got everything he wants now. That was the initial conception of the script.

Honestly, during COVID it was written very fast because I was doing nothing. It was a blessing in that way. When I wrote it originally, it was supposed to just be a distraction, and we were gonna get back to that other movie. That other movie kept increasingly seeming unrealistic, while this one kept seeming more realistic. So everybody who I was talking to about that other movie, we were like, “What if we made this one?” So we sent Colin an email and he said yeah. We have gotten to see it with an audience which is great. I don’t know if it’s always a boisterous, laugh-out-loud comedy to people. Maybe certain parts are.

That scene with Jessie Pinnick specifically is pretty laugh-out-loud funny.

RMB: But, you know, we go on Letterboxd and a lot of people are like “It’s such a cringe comedy,” which I guess it is, it’s just never the way we were thinking about making it. So, it’s interesting to see the initial feedback about the film in that way.

When Drew says “This is a form of discrimination,” to his Black boss, I thought that was laugh-out-loud funny, but that’s just me…

RMB: Well, thank you, Kat. That’s very kind.

I did want to ask you about this James Baldwin quote in the press kit, “Freedom is hard to bear.” Is Baldwin a big influence on you?

RMB: So, between you and me, I know it was pulled out and placed in the IndieWire article with the trailer… Seeing this out of context, I think quoting James Baldwin in a movie about a white guy who quits his job seems maybe a little tone-deaf. So I was like maybe we should go back and take that out of the press kit…

Are there any other influences on the film, either thematically or visually, that you were showing the cast and crew as a reference point?

RMB: We talked about Elaine May, we talked a lot about THE HEARTBREAK KID specifically. We talked about Albert Brooks some. We talked about Éric Rohmer, especially the way those movies looked and felt. They’re these kind of gorgeous, idyllic European summer movies with these characters who are so in the throes of their dramas. But the movie has this light touch… You know, Greta Gerwig was just on The Criterion Channel and she used such a perfect term. “In a minor key,” I think was the term. That idea was really important to us. There’s this guy, his problem feels very deep to him… There’s this totally beautiful world around him—Brooklyn, couldn’t look nicer—that he just can’t seem to do anything with. So, that was kind of a big influence as well.

There’s so much to grasp onto that he grasps onto nothing.

RMB: It slips by him. I do think that’s what Baldwin is talking a lot about, and he’s obviously talking about the impacts of how this can lead to evil, but he does talk a lot about America as being confused. Not in touch with itself. A lack of self-honesty. And I do think that’s kind of ultimately Colin’s character’s issue. He cannot sit still long enough to be honest with himself. That’s why he ends up back where he started, and that’s the cosmic joke of it. That’s where we were trying to come from in mentioning that. We talked a lot about Bob Dylan, too. “Living outside the law, you must be honest,” in “Absolutely Sweet Marie.” Drew was a guy who got himself out of some sort of system he felt like he was stuck in, and, because there was no self-honesty once he was out of that, he couldn’t sustain. So, that was another way of looking at the same feeling.

I feel like Drew would appreciate the Bob Dylan comparison. Do you think this character is specific to a time and place? New York in the 2020s, or is it more universal? Could it have been made in a different time or a different place?

RMB: This guy and this problem, at least in America, have probably always existed. This guy exists, but it’s maybe the attitudes and the beliefs and the distractions and the things he feels like he needs to chase, or the way that he feels like he should feel if he wants to live up to an idealized version of himself. What he’s pulling into himself, these things are of the moment. If he wasn’t in Brooklyn, if he was a guy who was living somewhere else, and there was a different set of attitudes and beliefs floating around him, he might have a completely different set of beliefs himself. The root of what his issue is could be kind of timeless, but what he’s decided to fill himself up with as a result, is very based on the time and the place that he is occupying.

You’ve also talked a little bit about The Great Resignation, and with FREE TIME you’ve given an image to it: the corporate guys living in their tent city. How did you overlap these political and personal ideas so seamlessly?

RMB: I hesitate to think about it too much as a political film. It’s lightly tip-toeing in that direction, but I don’t know if it ever goes so far that way that it would feel safe to label it as such. But, I guess it’s not really for me to decide. Originally, I was working with someone, a DP on the movie who ended up not being able to do it, and his main concern was “Well, I just don’t know if somebody would quit their job like this. Do people do this?” And a year later, he sent me The Great Resignation headline, and he was like “I was wrong about this one specific thing.”

Obviously, in relation to labor and capitalism, those are political things, but our relation to them is somewhat spiritual. I don’t know if the movie is as concerned with a direct political application as much as it is concerned with when you’re spiritually lost. To Drew, politics becomes just another thing that might save him in the same way that being in a cool band, or getting laid, or spending time in nature might. And none of these things can save him because he doesn’t have an honest relationship with them, and he doesn’t have an honest relationship with himself. It’s a spiritual problem, in a way—it is personal. I suppose it relates in that I don’t know that we can have much hope for our political future if we don’t have some sort of spiritual foundation.

Do you have any future projects on the docket that you can talk about?

RMB: We were talking about wearing multiple hats earlier; many of the people on the team write and direct and make their own films. So, even since we’ve shot the movie, many of those people have already shot their films, or they’re about to go and shoot a film. I’ve been involved in some of those projects in various different capacities. So, that’s really been the focus since we’ve actually completed the film, which has been awesome. I’m very excited to see those projects get out there in the next year or two.

You can see FREE TIME, written and directed by Ryan Martin Brown, at Quad Cinema starting March 22nd and in LA at the Landmark Westwood on March 29th!

Comments