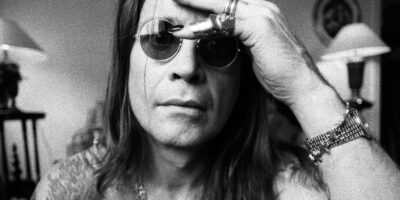

It’s a memory I’ll never forget. It was one of the most dreaded and consequential days in the life of any American youth: the morning of the ACT. I struggled with insomnia through much of high school and sporadically throughout my life; anyone who’s met me knows that it’s not unusual to see me awake at all unholy hours of the night. So, of course, with the weight of an all-important standardized test hanging over my 16-year old head, and despite my best efforts to get to bed at a reasonable hour, my body decided not to cooperate, and I found myself wide awake after a few restless hours staring at the distressingly small numbers on my bedside clock. After a few more hours of anxious rumination and the certain knowledge that my entire future had been destroyed by my inability to get some shut-eye, I came to the realization that sleep wasn’t coming and decided to get out of bed. Bleary-eyed, exhausted, and distraught, I sat up and reached over to my trusty nightstand radio (tuned to 97.1, WDRV The Drive, Chicago’s Classic Rock) and turned it on. What came next is seared into my mind as though it were yesterday. With the clock reading 4 A.M. and the sun not yet even peeking over the horizon, the voice of stalwart overnight DJ Greg Easterling came drifting out as he finished his preamble for the next set of tunes with three simple words: “…and now, Rush.” The iconic shredding guitar and cascading drum fills of the intro to “The Spirit of Radio” filled my room, and I felt myself overcome with an indescribable motivation and energy as Neil Peart’s poetic lyrics filtered through my ears and into my beleaguered brain:

“Begin the day with a friendly voice / a companion unobtrusive

Plays that song that’s so elusive / and the magic music makes your morning mood

Off on your way, hit the open road / there was magic at your fingers

For the spirit ever lingers / undemanding contact in your happy solitude”

It was the perfect song at the perfect time, the direct shot of confidence and adrenaline that I sorely needed, and I knew right then that everything would be OK, that I would crush my ACT and be on to the next challenge before I knew it. In some ways, “The Spirit of Radio” is the quintessential Neil Peart song. His performance on the kit is simply monstrous, effortlessly jumping between styles, moods, tempos, and time signatures as he provides not only the song’s rhythm, but also its background color, its bombast, its very pulse. The song’s lyrics are among Peart’s best, striking a delicate balance between reveling in the power of music and excoriating the industry that profits off of it. His words are both celebratory (“Emotional feedback on a timeless wavelength / bearing a gift beyond price, almost free”) and damning (“But glittering prizes and endless compromises / shatter the illusion of integrity”), all capped off by an incredibly deft repurposing of a classic Simon and Garfunkel lyric (“For the words of the profits were written on the studio wall”). “The Spirit of Radio” is an absolutely titanic track, the ideal opener to one of the band’s best records, accessible and radio-friendly without sacrificing its technical complexity, a song that almost feels undersold being played in any place other than a massive, sold-out arena. It’s a song, as all the great Rush songs are, that manages to capture and showcase the greatness of all three of its members in equal measure. But the heart and soul of the song lies at its center: the center of rhythm, the center of concept, and in many ways the polar center of the band, Neil Peart.

I can count on one hand the number of musical acts that have been more important to me in my lifetime than Rush—for fuck’s sake, I’m literally named after one of their songs (“Jacob’s Ladder”). The news of Neil Peart’s passing devastated me more than I can communicate, but as I spent last year in mourning, listening to Rush records on repeat and writing this very piece, the feeling that has most shone through the sadness has been one of immense gratitude. There is no Rush without Neil Peart, so even though Peart will never read this (nor Geddy Lee or Alex Lifeson, probably), there’s just one thing I’d like to say to all three members:

For over 40 years and 20 albums of some of the best rock music ever made; for three stunning live shows, each one of which left me exhilarated, hoarse, and wanting more; for the countless hours spent laboring over bass charts like “YYZ” and “Freewill” until my fingers bled; for pushing and inspiring thousands of others to push music in new, exciting directions: thank you.

Ride on, ghost rider.

— Jacob Martin, Music Staff Writer

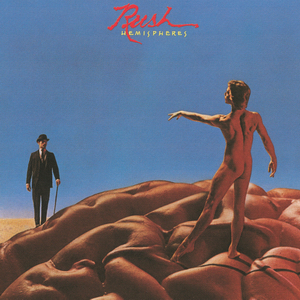

“The Trees” from HEMISPHERES

I first remember actively listening to Rush in eighth grade with my dad. My cousin had just given me a copy of Coheed and Cambria’s GOOD APOLLO, I’M BURNING STAR IV and I was playing it 24/7, prompting my father to go buy Rush’s SPIRIT OF RADIO: GREATEST HITS and tell me: “Listen to this instead of that shit.” While I never stopped listening to Coheed, I did fall in love with Rush.

Listening on my Walkman or in my dad’s truck, I realized that I knew songs like “Tom Sawyer” and “Limelight” from my parents listening to Southern California stations like KLOS or ARROW 93.1 (Pre-Jack FM), but the first non-radio cut that really grabbed me was HEMISPHERES’ “The Trees.” A political allegory that explores our social class system and the inequality within it, the song focuses on maple and oak trees battling it out for access to sunlight. Real deep, nerdy shit that a ninth grade Tolkein fanboy instantly ate up. The opening guitar comes straight out of a Renaissance fair before building into pure ‘70s stadium rock power chords, with Neil Peart’s fills and flourishes carrying the song from section to section. The first instrumental break finds Peart playing various woodblocks that imitates the chirping of birds over Geddy Lee’s pan flute synths and it sounds straight out of the troubled forest that the song is about. Slowly the song builds back up into the verse riffs for its conclusion, which finds the bickering trees “kept equal by hatchet, axe, and saw.” It’s a story that is as relevant as ever, and a perfect demonstration of Peart’s ability as a lyricist to have a finger on the pulse of society while also staying true to his grandiose and literary tendencies.

Over the years as I began playing music more seriously, I would delve deeper into Rush’s proggier works like 2112, A FAREWELL TO KINGS, or the rest of the tracks on HEMISPHERES, and my appreciation for not only Peart’s talent, but the talent of Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson, grew tenfold. I was lucky enough to catch them on the R40 tour at the now-demolished Verizon Amphitheater in Irvine, where at the time I had just seen Van Halen. And whereas I skipped Alex Van Halen’s drum solo to take a piss and get some beer, you bet your ass I was standing up in the back of the lawn to watch Professor Peart work his magic on that drum kit. My mouth was open the entire time—”Exit The Warrior.” [Jake Mazon]

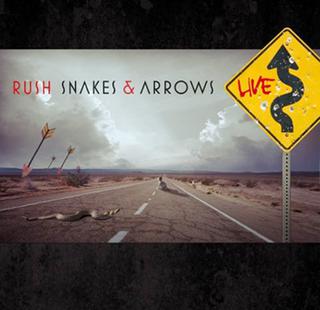

“Malignant Narcissism” from the SNAKES AND ARROWS LIVE

When I was 13 years old, on Memorial Day weekend in 2008, I got into a tiny little Geo Metro with my dad and his friend and drove eight hours to the Columbia River Gorge. I hadn’t really heard of this band I was supposed to see, but I spent the whole ride up listening to the two of them gab about guitar riffs and such; at the time, I was naive enough to think that the smell I was smelling was a skunk that had found its way into the crowd and sprayed someone.

In a 2015 Rolling Stone profile, Peart said that he “set out to never betray the values” that his 16-year-old self had. Peart’s contributions to Rush both as lyricist and drummer perfectly encapsulated that. His lyrics were ideological and high-minded, and his drumming was unfailingly experimental and ambitious. But, as self-serious as Rush’s music occasionally could be, their live performance delivered just as much youthful goofiness. At this particular show, they featured a video cameo from Rick Moranis and Dave Thomas in character as Bob and Doug McKenzie, cooked several rotisserie chickens live on stage, and played for three-and-a-half hours, clearly having a great time doing it. The Snakes and Arrows tour also featured a 10-minute drum solo in the midst of (at the time) new album cut “Malignant Narcissism,” making full use of Peart’s impossibly elaborate live drum setup, that walloped my little brain with every hit. He used samplers, he had a perfect balance between rock and roll aggression and relentless precision, and he knew when to break the grand science fiction façades that they created to have a little fun.

Rush is a band for the kids. For me, personally, they served as a gateway into some of the weirdest corners of rock, and even music in general—I’ll never forget how seeing him play that solo was the first time that live music moved me in the way it does now. I have a very strong feeling that I’m not the only person out there who feels that way (see: the rest of this piece), and it’s heartbreaking that the next generation of weird, adolescent music nerds won’t have that experience. [Adam Cash]

Rush is a band that has been meme’d into oblivion, partly because of the fervent fandom of the degenerate protagonists in TRAILER PARK BOYS and partly because longform solo-ing in odd time signatures was written off as indulgent shortly after bebop stopped being in vogue in the late ‘60s. However, if you were also an awkward prepubescent seventh grader taking out their maladjustment by way of classic rock nerdom, Rush inarguably exposed you to musical catharsis in your tweens. My dad inadvertently revealed Rush to me in the fifth grade when he gave me his preloaded iPod Nano in an attempt to make me cooler. I grew up Revolutionary War reenacting in the Virginia suburbs, and while I am now grateful for that experience because it led to me learning how to drum, it also ostracized me from most of my decidedly more normal sports-loving peers. Largely because of the hatred for music released post-1940 that my rudimental snare teacher had instilled in me, I felt immense guilt any time I didn’t loathe when one of my dad’s contemporary choices came up on shuffle. Rush is one of the few bands that is truly there for us drummers, and the first time I stumbled upon the precise percussion on “Limelight” and “Spirit Of The Radio,” I finally found respect for modern musicianship.

For Christmas in the seventh grade, my parents put the RUSH IN RIO DVD in my stocking. I put off watching it for a few weeks until I found myself home sick with a nasty cold and nothing better to do as a cell phone-less 13-year-old. I’d already watched Rush live videos on YouTube, so I knew Neil Peart’s eccentricities well. However, two hours of close-up shots of Peart’s 360-degree drum kit being beaten to shit under flawless sticking before a crowd of thousands of roaring South Americans is enough to blow any impressionable percussionist’s mind. After the video played through and my Xbox 360 played the menu screen on infinite loop, I powered through my fever and badly emulated Peart’s more memorable fills and solos. My main memories from the seventh grade are taking homework breaks in my dad’s basement to half-play Rush songs, hoping my parents didn’t hear me screaming the blatantly incorrect lyrics of Geddy Lee’s vocal parts to myself as I deafened my right ear with a Meinl China cymbal. Unfortunately, I found out at a family dinner my sophomore year of college that my dad and stepmom had indeed heard every warbled “Living in the limelight / Of university” that I hollered aloud during basement drum practice.

Two autumns ago, I found myself unironically gravitating towards Rush during a short-lived phase in which I tried to get myself into going to the gym. Though my tolerance for deep cuts from The Holy Trinity of Rock had, like my ability to run two miles, decreased since my youth, it was hard not to headbang along to the symphonic tom-tom fills in “Tom Sawyer.” Though I’ve stopped playing an eight-piece kit with seven cymbals as I’ve become more of a jazz-leaning indie musician, I still can’t help noodling along to the mashed rhythms of the song’s mammoth drum break during respites in band practice. Watching the live version on RUSH IN RIO is a childhood memory that undeniably plays a large role in why I continue to be an avid drummer almost 16 years after I picked up sticks for the first time. Rush is the first group that taught me to appreciate 20th century playing, the first band I argued with my mother over stanning, and the first band I taught myself to write off in an attempt to be cool. Though I may no longer play progressive rock, it’s hard to imagine a world in which my discovery of Neil Peart isn’t the reason why I keep walking down the frequently unrewarding path that is being a percussionist, and plan to keep going until my body fails me. [Ted Davis]

Comments