You probably hate your job. Who can blame you? There’s no dignity to be found in treatment as an automaton milked for as many hours with as little pay as possible. Work, as we currently know it, is soul-shattering. But what if we could aid and abet in the active betterment of our fellow man? What if we could focus our efforts on sharing as much of ourselves with each other? Meaningful work can be the difference between the dark and the light. To make a concrete living off of your own perceived worth is not only self-serving, but a genuine act of service to anyone who may cross your path. Joe Gardner, the main character of Pixar’s most ambitious effort in a decade, SOUL, streaming exclusively on Disney+, travels through multiple states of existence to come to the conclusion that maybe his passion for music, a passion he transfers into his lesson plan for the public high school he instructs at, pales in comparison to the act of sniffing a flower.

It’s an odd revelation. Of course Joe wouldn’t sit back and smell the roses while trapped in a cat in a life-or-death race to reclaim his body with a make-or-break, street-side ritual so he can fight for his dream job. The man’s busy! SOUL is so caught up in Storytelling 101 that its explosive climax, this stunning montage of the finer moments in Joe’s life, simply doesn’t land, and it’s frustrating. It’s one of the best sequences Pixar has ever assembled, a moment so pure that you can watch it entirely out of context and weep all the same. Instead, I’m wondering why the You Seminar in The Great Before bitterly painted Joe’s life with his failures. If these souls cannot taste or eat, then why the fuck does the Hall of Everything have a fully stocked kitchen? Was Joe really the first soul to escape The Great Beyond’s conveyor belt? Every Jerry sure acts like it. Alice Braga has a lovely voice that distracts from the pedantic world-building, but that’s exactly what I’m trying to say: I just want to listen to Alice Braga’s lovely voice. I do not need her to list out more laws. I literally just want the sound. It’s that TENET thing: your movie says “Don’t try to understand it. Feel it,” but it becomes immediately clear that instruction is not meant for you, the viewer. It’d be a much better time if it was, but instead, here I am learning the hard way that, in order for your piece to function in any capacity beyond flashing lights on my television screen, all I have to stimulate my ape brain is listen to your lecture. What’re they handing out with Happy Meals? Plushies of a pencil-mustached grown man and blue blobs with eyes? I bet SOUL is a merchandising gold mine. The film is already too stark and dull for children, so why not chase the reality of a loser who can’t locate his own sense of satisfaction? Nix the cartoon spirit world completely and let Kemp Powers make his KIKI’S DELIVERY SERVICE. The most valued animation studio on planet Earth can afford it.

Oh.

Hoo boy, we really took off to the races. I think I had some of what the writers at Pixar are eating: SOUL’s opening 20 minutes are the worst kind of lightning-fast, a table-setting rat-a-tat of rules and mechanics openly baiting Act Three pay-offs. Joe’s mother exists for his breakthrough, his friend Curly lives to provide the inciting incident, and his star student, Connie, hangs around to validate his guidance. Pixar’s always been staunchly story-first, but their skill, once remarkably invisible-seeding, has since transformed into jitteriness. One of my favorite parts of TOY STORY is that Hamm or Mr. Potato Head or Rex do not need to exist. What do they do? They just hang out, and the movie’s all the more incredible for it!

It’s a shame, because SOUL’s lush animation is so airy, every sugarplum hilltop soft enough to skydive into as every corner of The Great Before sees foam cascading atop holograms. Heavenly daylight refracts off feline fur, the city streets bustle with the appropriate blur, and Pixar’s New York City is painted with comfortingly warm Autumn tones. When the film is able to slow down from its “however, therefore, and so” plotting, it really is a privilege to soak in. All the while, Reznor and Ross’ synth adaptation of Giacchino’s plucky strings precision-strike your wonderment triggers—turns out, they’re pretty good at what they do. This is a movie you want to be in, a world both safely recognizable and foreign to each of your senses, but you have mere seconds before the bullet-train plot kills the buzz. A lot of shit just happens for the sake of happening, and against four different ticking clocks, no less. Nearly every spoken line of dialogue is in service of force-feeding the statutes and regulations of transcendence. How peaceful. It’s a tiresome story philosophy of characterizing abstracts by giving them task after task. Even Joe’s an abstract. I threw my head in my hands the moment 22, a burgeoning soul-in-the-making touring Earth voiced by Tina Fey, ripped Joe’s pants, forcing them on yet another panicky detour—I was just exhausted. Every moment must be immediately precluded by a new problem.

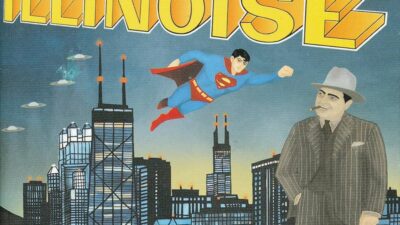

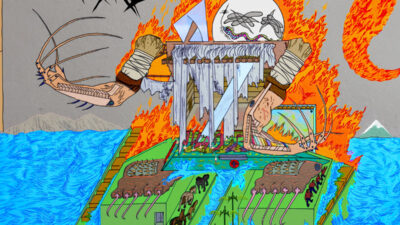

The further the Bay Area animation studio strays from its explorative roots of sprinkling fantasy onto the banal, the more it’s prone to demystify the great unknown wonders of the world. It blows. Were we not punished enough by INSIDE OUT? Our main character looked like if Kate Gosselin and Marge Simpson were Cronenberg’d together, but much like his previous interior outing, where Docter made the expanse of the human mind resemble a trash depot, SOUL bureaucratizes the ethereal into the DMV. Complete records of our most holistic selves are… Stuffed in endless rows of filing cabinets. There’s a throwaway joke about there being millions’ worth of dead Garcias. Yeesh, man. This approach works if SOUL were a heavy-handed allegory for the state of the Holy Spirit, some big-budget presentation by a Wisconsin youth pastor: it works if it were a Veggie Tale. Alas, this is still the closet to a Miyazaki that Pixar’s ever gotten—characters barreling deeper into inescapable, immutable realities, forced to change and adapt after being prematurely yoinked from their established path. Whereas Studio Ghibli’s outputs feel sourced from the same worldview, the repertoire’s repeated imagery and shared design philosophy ultimately creating a cohesive body, Pixar returns to the watering hole like they’re roaming an Ikea. Tasting pizza for the first time registers via recycled assets from RATATOUILLE and INSIDE OUT, its surprise second-act body-swapping suffers from BRAVE syndrome, its grand finale apes TOY STORY 3’s furnace fake-out, and it even sprinkles a few flecks of THE INCREDIBLES 2’s diatribe on screen addiction impeding on our imperative to live in the moment.

Before the hijinks hit.

On the trip to Ikea, the writers also seemed to peruse a desolate thrift store to score a VHS of SEE NO EVIL, HEAR NO EVIL, co-opting this spectacularly old school Gene Wilder/Richard Pryor type high-concept conceit where the Black man is a cat and the white woman is the Black man! Later in the film, 22 sprints down a subway tunnel in Joe’s body and runs into a pitch-black void, in a visual reference that all but directly indicates that it’s GET OUT’s The Sunken Place. I was on edge: is this movie really going to be about a Black musician sacrificing his time on Earth so Tina Fey can get a shot at living? It’s Disney functioning in the 2020s, the sky’s the limit for tone-deafness. And until the final three minutes, that was exactly what SOUL was doing. Fey inadvertently code-switches and discovers the wonders of the barber shop. These are certainly *choices* (never cast Tina Fey as a character meant to be sympathetic—it will backfire every time, and even she knows this). Jamie Foxx carries the film, but his vocals float on the track; the actor’s delivering his lines with more animation than the character model allows, so you’ll often see Joe say words that his mouth didn’t even form. Pixar went through the trouble of creating a hyper-real New York City, but their star’s lip-sync doesn’t even match up? It’s so weird.

The real trouble comes when SOUL’s core dramatic dilemma lands with a resounding thud. After a lifetime of professional rejection, glumly resigning to teaching high school band to students hungry for an easy elective and dealing with a dearly beloved mother who sees his art as a personal waste, Joe lands a dream gig, a gig with steady pay that connects with his personal desires, and a gig that his mother shows up to with rousing enthusiasm and support. When the bandleader tells him that they’ll come back to do it all over again tomorrow, Joe is… Disappointed. It’s a difficult plot beat; God knows we’ve all been pierced by the arrow of divine dissatisfaction. It’s true. This happens in the real world. But, wait, hey, I forgot to mention, by this point, Joe has died twice and suffered a temporal state where he could not taste, feel, or recognize his own flesh. Call me crazy, but I think if you came back from that, the first time you touched a piano again would be fucking religious.

Maybe I just fundamentally disagree with SOUL. Is life’s value really found in centering on the self? From encouraging a star trombone player to pursue her craft, or inspiring Curly to keep his sights on a career in music, to working tooth-and-nail to find 22’s spark, SOUL tees itself up as a film about the value of instruction and education. Our life’s meaning is the ability to teach, imparting your soul unto others as they unlock their personal meanings: this isn’t me trying to rewrite SOUL, this is me actively interpreting the first two acts of the movie! I suppose Docter wasn’t keen on revisiting the third act lessons of UP, an anti-materialist fable of passing the weight of your own experiences onto those you love most, but each film since has been a pale, off-key echo of his major masterpiece. Pete Docter and co-director Kemp Powers’ latest kind of enabled my own insularity. Sure, in SOUL’s soul of souls, it’s this refreshing lesson of refusing to learn from your failures, foregoing that masochistic self-exorcism and focusing your life’s path on redefining your victories. Spending formative moments with a loved one is a grand slam. Every breath you take is a dub. The reason to live is to live.

That’s wondrous.

But it’s also not really what SOUL is saying.

It claims that it is, but it’s pushing this idea that living your life is the reason to live. The proof’s in the pudding with how Docter and Powers depict the jazz band’s jamming: the art of that genre is reacting to your fellow musicians. Jazz is a collective effort. The moment you enter “The Zone” and tune them out is the moment you jeopardize the riff. We never see Connie’s life, nor Curly’s, nor Joe’s mother’s. It’s all Joe. You take a single step away from SOUL’s gorgeous mural of our humanities and you see an entertainment company of such profound power. Disney is the same company that largely decides the social and fiscal fabric of entertainment, the same company that reinstated executive bonuses in the first quarter of the pandemic while furloughing thousands of employees, and the very same company that, after nearly a century of making billions off telling children to live for their happily-ever-after, is teaching the lesson that you’ll be okay when they tell you no. If we’re exploring successes and failures, perhaps it’s wise to first dissect the machine that helps objectively define them. SOUL is a clever diversion, but, buddy, don’t act like you didn’t make this mess.

Comments