On April 12th, 1988, the U.S Supreme Court granted American chemical company DuPont a patent license for the OncoMouse: a rodent genetically modified to carry an activated oncogene. These mutated mice have a higher chance of cancer which, subsequently, make them convenient sacrifices for oncological research. Turning a living and affective creature into a transgenic aberration is an inconceivably cruel act; yet, because the OncoMouse is a non-human, whose subjection mollifies our bipedal needs, its pain is somehow subsumed into the grand narrative of human advancement. This is how, despite obvious ethical qualms, the OncoMouse became the first patented animal—born, bred, and sold by technoscience corporations for the so-called “greater good of man.” The tragedy of the OncoMouse is not an unfamiliar tale: it is also the story of woman. Before there were red-eyed lab rats, breasts, buttocks, and vaginas were the prima sites of experimentation, disfiguration, dissection, destruction, and dis/re/production—all enacted in the name of progress. With their bodies circumscribed by Man’s microscope, the OncoMouse and Woman are like sisters, both condemned by the forces of Enlightenment.

Cronenberg’s latest feature, THE SHROUDS, brings these matrices of technoscientific experimentation, biopower, and gender into the cinematic form. The film is told through Kash (Vincent Cassel), inventor of “the shrouds”: a controversial burial technology that allows its users to observe the carrions of their beloved from the convenience of their phones. The idea came to Kash shortly after his wife, Becca (Diane Kruger), passed away from cancer; unable to part with her husk, Kash uses the shrouds to remain connected to Becca’s atrophying flesh. While some find this demystification of death appalling, Kash finds solace in monitoring her decay. For him, witnessing grounds him in the present, while opening a sense of intimacy and clarity with his once-enigmatic wife. Kash’s interest in Becca’s corpse is, however, not solely an idiosyncrasy of grief. He constantly surveils Becca’s shroud—refreshing throughout the day, checking for peculiar growths, and keeping images of her bones by his bedside. It is as if he is laying claim over Becca’s body, treating it like his prized possession: a disciplined object that cannot resist its confinement or visual violation.

With Becca’s commodified corpse as ground zero, the shrouds become a lucrative business. Kash’s strange enterprise is especially a hit amongst the rich, and it soon catches the attention of a dying Hungarian tycoon and his wife, Soo-Min (Sandrine Holt), who offer to invest in the system so long as it’s fortified from potential Russian and Chinese interference. Around the same time, several shrouded bodies—including Becca’s—start developing strange bone growths. Kash starts to suspect that these points are discursively linked; perhaps Becca’s death was imbricated in a multiscalar drama, involving “rogue states” with pernicious cybernetic goals and Becca’s former oncologist—who Becca’s twin, Terry (also played by Kruger), suspects of malfeasant medical experimentation. Whether these trails lead to the truth, or are conspiracies gestated in the mind-womb of a grief-besotted widow, is unclear; but in either narrative, Becca’s body is constructed as a playground for technoscience.

It is no coincidence that Becca is the generative site of technoscientific activity since, after all, she is a woman—scrap paper for Virtruvian Man’s craft. In that sense, the parallels between Becca and the OncoMouse are vast. Both are toys for oncological treatment (purportedly), surveillance technologies, and fetishization; the similarities are even more apparent between their handlers—Kash and DuPont, respectively—who possess the copyrights to their corporeal. The uncanny resemblance between Becca and the OncoMouse is heightened by Kruger, who plays Becca without vocal inflection. Kruger’s affect—or lack thereof—is characteristic of a Cronenbergian ontology. On the other hand, her stoic and obedient aptitude recalls that of a perfect lab rat.

What is real and what is heartbroken delirium is further muddled by Kash’s recurring dreams of Becca, whose body, with each hypnagogic conjuring, becomes more disaggregated. No matter how much emotional progress Kash makes in daylight, the night returns him to her: Becca is a ghost that cannot be exorcised by time or therapy. It’s hard, then, not to read THE SHROUDS as David Cronenberg’s grief manifest. Like Kash—who looks so much like the director—Cronenberg’s wife passed away after an attrited battle with cancer in 2017. Kash’s secular haunting is perhaps an extension of Cronenberg’s own, and it’s deeply sad to imagine the beloved auteur suffering to this extent.

The corpse is the organizing figure of modern society. Preventing death and administering life is the modus operandi of institutions such as government, law, medicine, education, and religion. In less material ways, as Foucault argued, the corpse also structures the way individuals are interpellated into these institutions; images of dead, sectioned, and dissected bodies intensify the viewers’ commitment to disciplinary structures which offer a sense of control and security over death. Whether or not we realize it, death is the axis on which everything rotates. No matter how deep we bury the corpse, it remains immanent in our everyday. We are always in death’s proximity. The imagined spatiality between life and death is existential ignorance.

What Cronenberg does exceptionally well is situating this classic Foucauldian thesis in our current epoch of technoscience: THE SHROUDS shows how digital tools and STEM research are not escapes from the primitive fact of death. With sophistication, Cronenberg also notes that there are gendered differences in how life and death are administered in today’s biopolitical regime. Not all corpses are made equal. It is women—the gatekeepers of life—who are the most inflicted, instrumentalized, bondaged, tested on, and watched: her body is sodden with histories of violence.

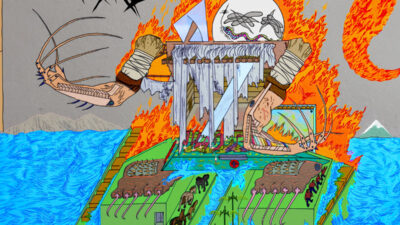

what a mind on vicky huang!!