Merry-Go-Round Magazine was at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival!

Folks, Sundance has officially come and gone, and soon so will our coverage. We’ve got a few more things up our sleeves, but after 32 feature film reviews, we’re nearing the point of hanging up our spurs until next time.

It’s difficult to form any takeaways: if anything, I made up my mind before embarking on a virtual Sundance and encountered nothing in practice that swayed me otherwise. Increased accessibility is good, and a shared hype window with the weirdos of Film Twitter made for a unified event weekend we haven’t seen since theaters closed, but a film festival with no in-person networking, no audience vibe checks, and no fervent buzz is not much of a film festival, but rather a series of increasingly complicated content dumps. On a programming note: a pretty exhausting slew of films, either about generational transgressions, isolation, or very explicitly about 2020. I see what you’re trying to do, and to that, I say… Incredible curation, but no thank you.

The New Frontier design team allowed for a cyber meeting place, but anytime I logged on as my human avatar with a floating photo of my face, I just got depressed. This is weird, dude, and somehow a more uncomfortable way to attend parties than silently drinking a rum and Coke in the corner until the one person I know who was also on the invite list shows up. I want to pick and choose what we normalize from at-home transitioning, and socializing will likely never be one of them.

Anyways, movies! More than ever! Let’s take a look at Sion Sono’s much anticipated PRISONERS OF THE GHOSTLAND, Maisie Crow’s fascinating AT THE READY, Christopher Makoto Yogi’s tender I WAS A SIMPLE MAN, Dash Shaw’s CRYPTOZOO, and *exhale* Jane Schoenbrun’s WE’RE ALL GOING TO THE WORLD’S FAIR.

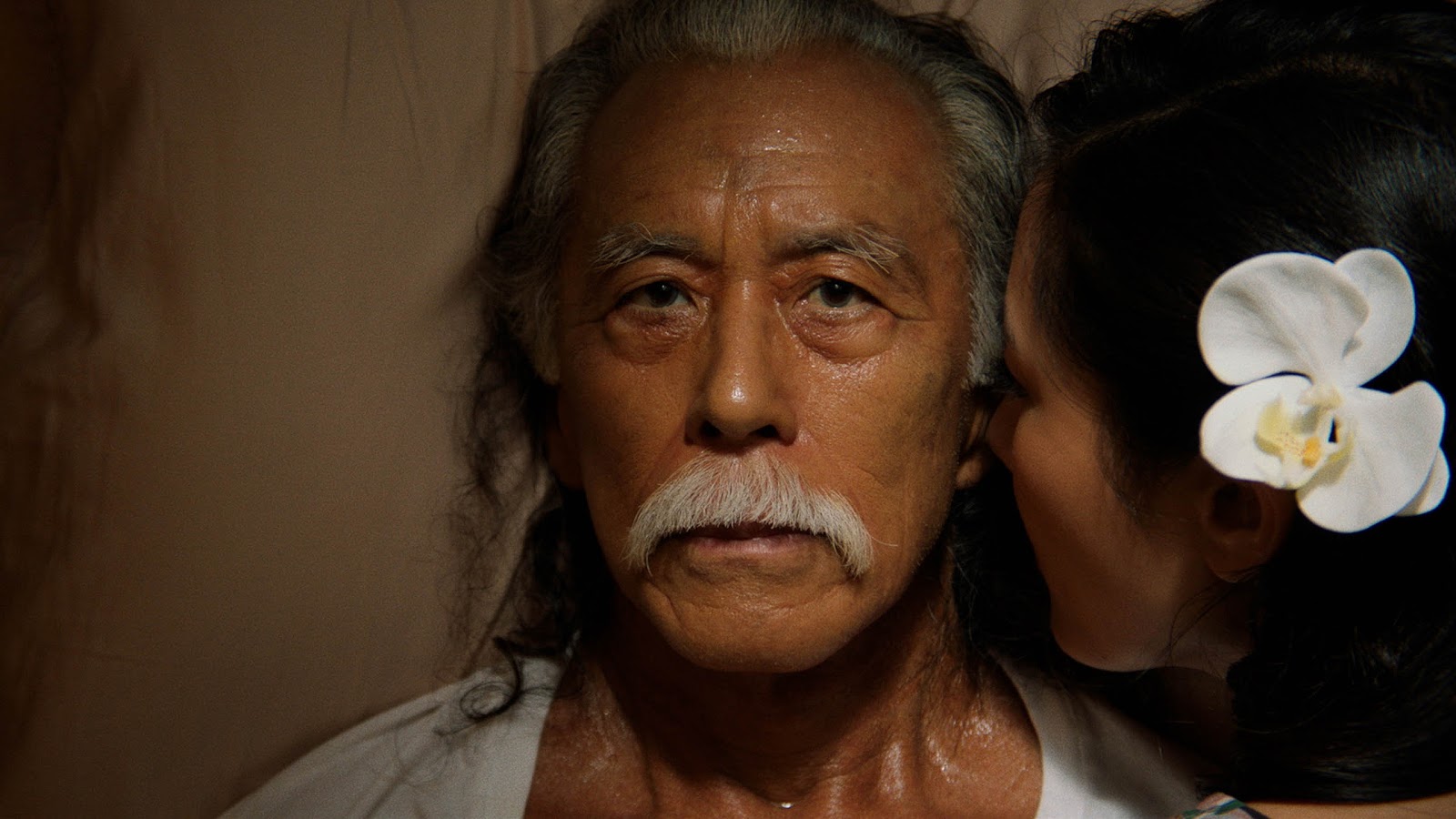

I WAS A SIMPLE MAN

Director: Christopher Makoto Yogi

Two older men look over the high-rise expanse from the railing of a parking garage, remarking “I remember when this was all beautiful green.” Honolulu has become the scab of Oahu. Masao Matsuyoshi (Steve Iwamoto) lives between the mossy cracks of nature and medical office waiting rooms, splitting his final days between a deteriorating reality and making peace with the ghosts of his past standing idly among the branches. I WAS A SIMPLE MAN all but directly credits its influences, the film coasting on the existential stupor of UNCLE BOONMEE and the moment-to-moment macabre tranquility of TROPICAL MALADY to explore the island’s generational timelines, historical and interpersonal. A fight breaks out between patrons and the pianist abruptly stops as the radio behind the bar announces Hawaii’s statehood: we witness the harbingers of death as often as we do the births of new loves, new myths.

Matsuyoshi lays in bed with lingering spirits and sinks into their slumber; body in decline, but the soul of a land and its native history prevail, no matter the sheets of concrete poured over them. Iwamoto has a wonderfully creviced face and Constance Wu, a cunningly utilized aspiring superstar as Grace, is perfectly postured, if entirely objectified, as more a spectral object than a cherished memory. With a wordy script that could be tightened, but should really have three quarters chopped off, with lines as plain-faced as “this island has changed so much,” turning a felt pain into an insecurity, I WAS A SIMPLE MAN is supremely confident until it’s critically not. A cut-and-clear, mediocre monologue from a young Grace about her future grandchildren carrying the marks of their ancestors in their minds isn’t delivered much better than it’s written. It’s so rare we indulge in Hawaii’s landscapes through the eyes of its inhabitants, the state largely defined by its real estate agents and the tourists they herd in; slice away at the lucidity, strip the gaze, and you easily have something here that stands alongside its mentors.

WE’RE ALL GOING TO THE WORLD’S FAIR

Director: Jane Schoenbrun

Pallid face, chronically unmade bed, sludge metal font on her band tee… In the unbroken opening of WE’RE ALL GOING TO THE WORLD’S FAIR, we see all the key ingredients that make for the lonely kids lost in the blue light, and observe Casey (Anna Cobb in her debut) film a World’s Fair Challenge video, a viral strobe-lit “Bloody Mary” self-harm ritual, for her YouTube. Jane Schoenbrun is no doubt a child brought up by online culture: they understand that most of our lives are spent finding solace in a four-wall room stacked with stuff and a lone pleasure screen with an empathy where many would choose pity. The people Casey watches are using the challenge as a platform to perform for views, going the extra mile to extend a meme’s lifetime by smacking themselves on treadmills, but she craves the feeling of that dysphoria herself, yearning for the promised effects of the World’s Fair Challenge’s explainable afflictions; anything that can explain the chemical imbalances of her own brain. Schoenbrun shares a hyper-specific period in a child’s life brought up in tech, with zero concept of hard drive space, dozens of hours of footage stored in Photo Booth, and perceptions of YouTube personalities so removed from reality’s that they’re modern Olympians.

For as much as it “gets it,” there’re definitely some lapses. Explicitly mentioning “CreepyPasta” feels so old school, like making your username CanterburyTales1392—CreepyPasta is basically as ancient, only mentioned in casual as a core tenet of the era’s storytelling. Even the boomer who makes it his username would acknowledge that. The film is almost too invitational in the end, at first plunging an unsuspecting viewer deep in the weeds of Online™ culture, then revealing its aspiration as an introductory text. Once we zoom out of niche pockets of the Internet, and it starts zoning in on a vlogging Zoomer’s (though considerably more docile) FIRE WALK WITH ME, the freedom of the form morphs into predictable storytelling, eerie psychological horror making way for a perfectly fine MARY AND MAX riff. Anna Cobb is magnetic, solidifying Schoenbrun’s incredibly delicate threading of narrative drama and documentary-type divulgence, but her counterpart, Michael Rogers, lays it on thick, delivering a theatrical performance in a film that’s been defined by performative socialization. They’re the only two actors in the movie, so you’re stuck with him, patiently awaiting Casey’s next self-inflicted exorcism. Watching on my laptop, I thought my video player had burnt out, the footage constantly buffering and my own wallpapers distorting. Of course, I was experiencing Casey’s desktop. I was experiencing Casey’s despair, her loneliness, and her fears. WE’RE ALL GOING TO THE WORLD’S FAIR is a formidable addition to the screen-life form, its techniques embedded in the overstepping of digital outreach opening the floodgates for IRL to bleed into the cyber meta. The real world’s fair is the fellow insomniacs we meet along the way.

AT THE READY

Director: Maisie Crow

It’s what every documentarian wants to hear, and I’ll give Maisie Crow this: AT THE READY taught me something new. I had no clue that in 2018, 800 Texas high schools offered in-school law enforcement training programs. Crow’s documentary focuses on El Paso, one of the most densely Mexican cities in the United States where the children of immigrants are being trained to further an emboldened wave of border authority goonery. Before a drug bust drill, the instructor vaguely clarifies that “somebody in this world, somebody’s doing this right now, for reals.” The instructor is later asked by a student on whether he should fire at a suspect who appears to be reaching for a weapon, immediately affirming the strategy. He assures the nervous student that “He’s gonna say ‘I didn’t know they were cops.’ That’s for the courts to decide.” You are the good guy, so have no guilt. We’re all partners, we’re family. The students’ parents pull the “there are good and bad people in all jobs,” but no one’s remotely close to assessing that the job in its purest essence is corrupted. How do you really conceivably accomplish this realization in cop land? These kids are so close to personal revolution, on the verge of splitting Left, but they’re encouraged into classrooms with proudly hung Blue Lives Matter flags.

The appeal of joining the club is to fend off a lonely high school experience, to find a group dynamic when it feels like no team wants you. These courses are boosting interest by exploiting legitimate cartel concerns, but also adolescent adrenaline, getting these teens jacked on the thrill of a no-knock warrant. This is how you groom kids into cops, this is how you create white Latinos, and this is how you get radicalized by the state to turn in your own. On a student’s trip to his father’s house in Juárez, the father asks if the son would use his prospective career to pull some strings and get him to the States to reunite with his family. The son replies “I’m not going to lose my job for you.” The course instructor makes his Ted Cruz vote loudly known, insinuating that O’Rourke’s stances will affect their potential paychecks. Law enforcement in El Paso is the only occupation where wages come close to matching the national average, recruiters hawking this statistic to potentials who grew up seeing their parents struggle to make ends meet. Of course, O’Rourke emerged from the grass a snake, but the hope he inspired, largely the hope he capitalized on, is ultimately the fix: some conceivable grasp at mandated change to combat Republicans’ decades-long preying on the desperation from salutary insecurities they themselves imposed.

On one hand, there’s a draw in following these kids, you get instant main characters and immediate focus—Crow’s good at it. On the other, this really is the bare fucking minimum for an exposé on indoctrination, never reaching out to surrounding grassroots organizations or city council members who either oppose or support these programs. And if it’s a narrative she’s chasing, then there’s a critical moment where Crow refuses to probe one of the instructors on why they shafted a certain student, suddenly flopping at even capturing the limited focus she dead-set herself on. The film opens real roughly, with snappy, clip-chimped montages setting the political stage, using real-world context as a soundtrack instead of, well, context. AT THE READY is frustratingly neutral, wanting to share the story from this made-up ideal of an objective POV, squandering its chances at vitriol against Texas for ruining these kids’ lives. AT THE READY’s subjects are asphyxiated in this fascist bubble, running practice raids in the school’s hallways as kids in leotards from the dance club wander in the background to their lockers. I should be startled by the junior officers rehearsing how they’d neutralize perps, but Crow’s focus pays off when the sight of a band student caught me more off guard than most jump scares.

CRYPTOZOO

Director: Dash Shaw

Take a passing glance at CRYPTOZOO and you immediately understand that this is genetically manufactured to pack a bowl for. This is FANTASTIC PLANET on THC, fully designed for the cuticle-picking midnight tweakers tracing the lines of its anarcho-primitivist-stoners hungry to storm the Capitol to literally return to the days of monkey. Is this a comedy? Michael Cera voices He-Man, gets brutally impaled by a unicorn, which then gets its brains slowly bashed in by the stark naked avenging girlfriend, and it becomes a bit clear that we’re about to get Charles Burns’ HEAVY METAL. At many moments, Shaw is going for irreverence, but the uneasy air of paranoia creates a legitimate discomfort rather than an intriguing synthesis of tone, switching gears to a startlingly somber eco-terrorist parable that constantly chooses savage violence. It’s painstakingly manicured animation and screenwriting not nearly mentally unwell enough to sing as a demented piece of blitzkrieg creativity. Many of the pieces are there! DOGTOOTH’s Angeliki Papoulia plays a Gorgon! Grace Zabriskie is the mythological beast militia’s general! There are contested debates over sustaining sanctuaries by turning them into shopping malls, letting the world know you’re normal by identifying as a sellable brand! These elements are at the core of CRYPTOZOO’s more astute incisions and heart-wrenching interactions, but Shaw’s attempts at authenticity are undone by his cynical postmodern fairy tale recitation, at this awkward standstill of legitimate honesty and parading above itself.

Don’t pack the bowl too full either, this is a gnarly trip. Fall asleep to it, nod off, get sucked into its jitters and jerked by its bitters. Its aggressive monster-movie-ness demolishes your sunrise high right as you’d been wanting to drift. The climax is striking, but such a radical left turn, CRYPTOZOO taking pleasure in violating its user agreement any chance it gets, regardless of how shiftlessly it approaches its analogues for racism, the military-industrial complex, and immigration; Shaw makes ZOOTOPIA read like Between the World and Me by comparison. Gruesome, dour, and putters out with this bloody heaviness poured over thinly conceived themes of cultural imperialism. How you want to make me sad is not worth the thought you failed to put into this! Sadistically melancholy, I never felt I was in safe directorial hands to dignifiedly surrender to what CRYPTOZOO desired of me.

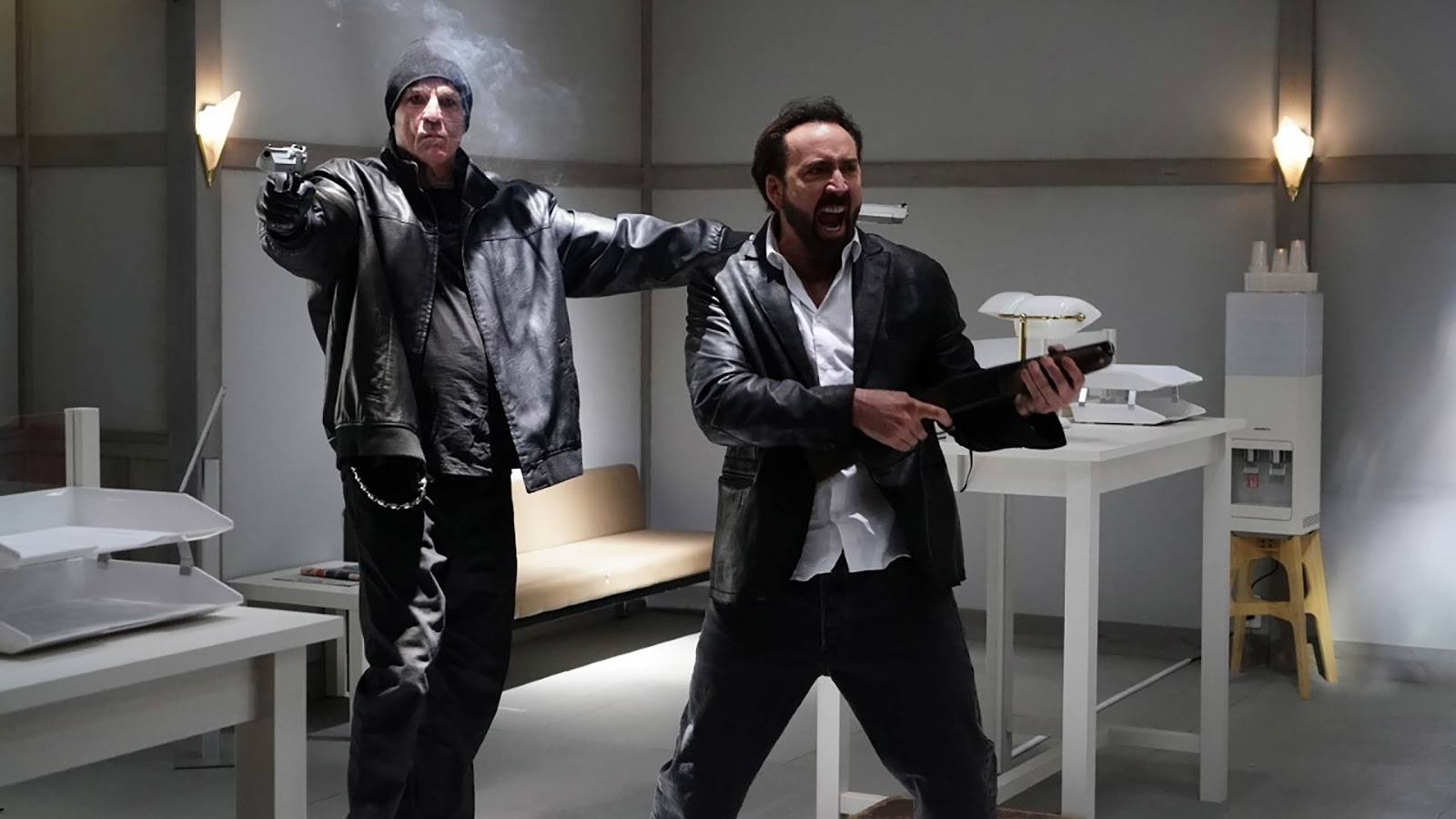

PRISONERS OF THE GHOSTLAND

Director: Sion Sono

There’s a chintziness to PRISONERS OF THE GHOSTLAND that makes WHY DON’T YOU PLAY IN HELL? look like GIANT, a solid portion of the budget meant for gonzo creativity instead funneled towards the English-speaking talent. Pairing Nicolas Cage and Sofia Boutella, the stars of 2018’s most feral exploitation pictures, is so inspired, let alone having an unrecognizable, toxic sludge’d Nick Cassavetes tag along to embody the pathos of a criminal’s guilt. They’re phenomenal presences, even if the indomitably physical Boutella gets the short-end of the stick, all strutting through the middle of nowhere with random stage and quasar lights in full view; Sono’s post-heart-attack clarity shines so warmly through the tale of outlaw redemption, but the old fella’s a little tired. Watching him work with Cage is a magnificent mix of soluble vision and completely lost in translation messaging, his shrieking and convulsing channeling Toshiro Mifune, yet it’s also a bit of self-sabotage.

Maybe it’s muscle memory, but watching English Sono makes me inclined to receive this as an impersonation and not a direct work from the origin. A lot of these preoccupations come to a head whenever we spend seemingly endless stretches with Bill Moseley’s Governor, a mustache-twirling turn in which the actor tries to embrace the aura of the character with a Colonel Sanders politeness, but lacks the panache to make the words (of which there are just way too many) sound like anything but noise. I’ve never been a Rob Zombie guy, and I’ve definitely never been a Chop-Top guy, so your mileage may vary.

It’s odd to call a cyber-feudalist Japanese western tame, but PRISONERS is, relative to previous works, a more-traditional-than-expected bubblegum blitz. Actually, I might be undervaluing things, this is a movie with radioactive samurai desert punks and villages where civilians use ceramic mannequins as armor, this still goes bizarro. Sono lives in this crossroads between Toshio Matsumoto, Roger Corman, and John Waters, three pills on their own that require individual swallows, let alone this fucking suppository cocktail, It’s a quintessential drive-in movie, one where you sense that its sets were hastily constructed, filmed on, then demolished just 30 minutes before you pull in to the pavement lot to watch the final product on a dim screen with an order of concession stand carne asada fries that will gift you a midnight pint of diarrhea. You could complain about the vacuous garishness or self-inflated bloat (or, often rightfully, his feckless treatment of women and minority cultures), or you could just meet Sion Sono on his own terms. It all depends which insufferable geek you want to be, and I’m the one who cheers when Nicolas Cage says the funny thing loud.

Comments