As a music fan, choosing your favorite artist’s darkest, most harrowing album as your personal favorite can sometimes feel a little self-centered.

For example, my favorite Mac Miller project is FACES, his 2014 mixtape that spends most of its runtime addressing his struggle with drug addiction, and his emotional state during a particularly dark stretch of his rise to fame. Especially in the aftermath of his tragic death in 2018, arguing that FACES is the best work Miller ever put out makes me worry that I might be inadvertently glorifying the struggle and pain that the mixtape was born out of, despite the fact that I find the way it writes about these issues to be incredibly insightful and poetic. When I listen to FACES and sing its praises, am I just being a voyeuristic tourist of another human’s pain? As music criticism and fandom has seemed to value intimacy and open discussion of trauma more than ever before, which has naturally lead to an increased commodification and fetishization of trauma, it feels especially uncomfortable for me to heap praise onto something so directly tied to the thing that killed him, despite how much I admire it as a piece of art. It’s not that I didn’t enjoy Mac’s other non-FACES work—I love SWIMMING almost as much, despite how painful the optimism and healing of that record feels when juxtaposed with his death that same year—but FACES continues to resonate with me in specific ways no other Mac Miller album ever has.

The tortured genius, the person with immense demons that sometimes outweigh their equally great talents, is one of the most prevalent mythological archetypes in show business. Even the phrase “tortured genius” is used to describe a list of names so long and iconic I don’t need to spout them off to conjure them in your mind. In music, in movies, in all other forms of art, we love these figures, and we especially love when they tell us the story of their struggles. As that type of confessional storytelling grew more and more popular in the realm of pop music, especially in recent years, it can feel hollow and cynical; I wonder if this trend is exploitative of the very real pain and suffering these artists went through. Are asking them to perform emotional turmoil for our entertainment? (A must-read tangentially related to this topic is Larry Fitzmaurice’s essay on what he calls Pop’s New Emotionalism). Even though I obviously never intended for this to be the case, I couldn’t help but feel that, by valuing FACES more than any other Mac Miller album, I was sending the message, “I liked your work best when you were clearly suffering the most.”

—

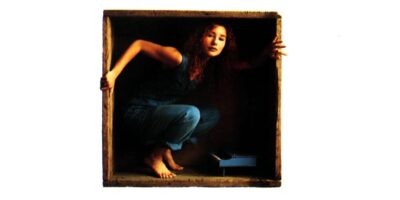

I have this same dilemma with WHAT WOULD THE COMMUNITY THINK, the third studio album from singer-songwriter Chan Marshall, aka Cat Power. Released 25 years ago, it represents Cat Power’s big breakthrough moment—her first release on Matador Records and the project that propelled her from lo-fi origins with albums like DEAR SIR and MYRA LEE to becoming one of the biggest stars in the indie music world. It’s the moment when her talents first crystalized into something truly special, the first time she got full creative authorship of the album she was making under the guidance of Sonic Youth drummer Steve Shelly. It’s also a snapshot of Marshall as, in her own words, a “very mixed up young person,” still struggling with alcohol abuse and as well-known for her unmistakable voice as she was for the meltdowns and crowd confrontations that sometimes ended with her sobbing in a fetal position on stage.

Like ‘90s contemporary Elliot Smith, who never looked remotely comfortable in the spotlight, Chan Marshall was someone who was clearly born to be an artist, but was almost too riddled with anxiety and discomfort in her own skin to be able to translate that natural ability into a career as a performer. In videos of her live shows from the late 90s, she often allows her bangs to hang completely in front of her face, barely making eye contact with the crowd and never participating in any sort of stage banter. It’s genuinely shocking to watch these introverted performances and then see clips like this one from 2006, where she’s working the crowd between songs and spontaneously bursts into a cover of “Crazy” by Gnarls Barkley, complete with dance moves. How are these two clips the same person, only eight years apart?

In the studio recordings, you could immediately tell that Marshall was an incandescent superstar, the kind of person with a voice so arresting that, even on her most amateur sounding LPs, her talent was undeniable. In earlier writing I did about her debut DEAR SIR, I compared listening to her voice on this album to watching a superhero awkwardly learn how to master their powers—it’s bumpy and rough around the edges, but every bit as emotionally potent as her most acclaimed works and, in some ways, more so. Even though every other Cat Power album is objectively better recorded and more technically polished than the earliest two, there’s something so compelling about listening to her stretch her voice past her limits as she tries to communicate the enormity and crushing weight of the emotions she is experiencing.

WHAT WOULD THE COMMUNITY THINK is at the midpoint between the earliest beginnings of DEAR SIR and her personal and artistic triumph MOON PIX, the album most critics and fans consider to be her best work and one that Marshall herself describes as “my salvation.” I won’t get too deep into MOON PIX or it’s haunting origin story here, but once you learn the fact that the album was written as a literal prayer to god during a bout of horrifying psychosis and hallucinations, the otherworldly power these songs seem to possess becomes easier to wrap your mind around. MOON PIX is still emotionally devastating, but has a strange kind of clarity and steely reserve that is unlike the uncertainty of previous Cat Power albums. If MOON PIX is the calm in the eye of the storm, WHAT WOULD THE COMMUNITY THINK is the storm itself, full of anger and sadness and about 15 other emotions that don’t have anywhere else to go.

—

The opening track of WHAT WOULD THE COMMUNITY THINK, “In This Hole,” is my favorite Cat Power song, and one of my favorite songs period. I could write an entirely different essay just about “In This Hole” (specifically its unforgettable use as a needle drop in the 1998 Abel Ferrara film NEW ROSE HOTEL), but anything I try to say about this track or my obsession with it will probably pale in comparison to the goosebumps you will get from hearing her play and sing it. The descending guitar riff that makes up the entire instrumental of this song (besides the tiny xylophone) is so innately melancholic and depressing, yet so warm and comforting at the same time. In the same way that falling back into depressive habits can feel like comfort and relief in the face of problems you don’t have solutions for, the guitar of “In This Hole” alone is enough to put me into a calm, almost meditative trance, but when Marshall begins to sing I become completely spellbound. “In this hole that we have fixed / We get further and further and further from what… we must do”

One of the most compelling things about Cat Power as a vocalist, especially in this era, is the way her voice can jump between emotional extremes from moment to moment, with her voice sometimes cracking from the strain she is putting it through, as she jumps from a dispassionate deadpan into an almost pained yelp. She can sound cool and confident in one moment and devastatingly vulnerable the next, but none of it ever feels like performance or artifice. A New York Times profile of Cat Power from 2018 describes Marshall’s mannerisms in person as “at turns glamorous, self-effacing, eloquent, self-hating, jittery, effusive, impenetrable, endearing, curious, frustrated and frustrating, a near-constant stream of consciousness and conversational tics,” and that overflow of humanity comes across in her music as well.

To say Marshall contains multitudes is clearly an understatement, and WHAT WOULD THE COMMUNITY THINK displays her complex, messy humanity more than nearly any other Cat Power album. In every song, you can hear her practically bursting at the seams with a constantly swirling mix of anger, fear, shame, longing, regret, self-loathing, love, and even a caustic sense of humor. These emotions don’t stay neatly cordoned off in separate songs either-they are always bleeding and blurring together, contaminating each other. Much like fellow ‘90s indie wunderkind Fiona Apple, even as a teenager and in her early 20s, Chan’s voice and songwriting had a world-weariness to it, having already learned by that age how painful life often is. When she sings lyrics like, “Brother is old and grey / And he’s only / He’s only seventeen,” or, “Father said he was going to give me something / Gave me hate” on the harrowing album closer “The Coat Is Always On,” it’s not hard to imagine the kind of familial trauma she has been through, and what could have made such a young person already sound so broken.

The volatile emotional state and vocal performances are complemented well by this album’s unique mix of influences and styles, combining the slide guitar and blues riffs of her Georgia country roots with darker indie rock and slowcore. She never stays in one mode or instrumental arrangement for more than one song, pivoting from the acoustic balladry of “In This Hole” to the stormy indie rock dirge “Good Clean Fun” right away to show the range she plans to explore on this album. There’s country-tinged rock tunes like “Taking People,” whose gorgeous use of slide guitar and dry humor sounds like it might have inspired the entire careers of artists like Faye Webster and Courtney Barnett. And then there are heartbroken, twangy love songs like “King Rides By” that sound like the early precursor to current indie folk artists like Angel Olsen and Lomelda.

“Nude as The News” is the closest thing to a ‘90s radio ready rock single this album tries to offer, which happens to be about the most radically intimate, un-radio song topic possible: an abortion she had at 20 years old. In this clip of a performance of “Nude As The News” from a French TV show, despite the fact that the band has the collective stage presence of a group of teens at a middle school talent show, the raw fury of this song and the way Marshall sings it turns an otherwise unmemorable performance into something magical. There’s no ripping guitar solos or pounding drums to make this performance feel propulsive and exciting, just Marshall’s voice, but what a superpower that voice is. This song’s engine is powered solely by the passion and righteous fury she packs into the delivery of lyrics like, “I still got a flame gun / For the cute ones,” and, “He’s related to you / He’s dying to meet you.” Even in the ‘90s, as angry pop songs were more in vogue on the radio than ever before thanks to the grunge movement, this song, and the album in general, feature a kind of unvarnished, messy anger rarely heard on airwaves, especially coming from women. The fact that it resonated so deeply with audiences speaks to how universal these feelings really are.

If there is a nitpick to be found on an otherwise exceptional album, it’s “Bathysphere,” a cover of a song written by Marshall’s now ex-boyfriend Bill Callahan from his time in the band Smog. The Cat Power version of this song is totally arresting, but throughout the track, there is a synth loop playing in the mix that is so grating and unpleasant to listen to that it makes paying attention to her interpretation of the song more difficult than it should be. But even this specific element, an artistic choice that I consider to be the album’s biggest flaw, I have a strange kind of admiration for. Similar to the way she would turn away from the crowd in those performances in the ‘90s as she sings the most raw and intimate parts of songs like “Metal Heart,” this production detail feels like Marshall saying “look away, this song I’m singing is for me, not for you to listen to.” This incredible live recording of a 30 min opening set from her time touring with the band Low shortly after the release of this album begins with the “Bathysphere” cover, only this time there’s no synthesizer or anyone else on stage, just Marshall and her guitar. Even still, when she’s not singing the verses, she spends most of the song mimicking a synthesizer melody with her voice, an indication that she wishes the sonic privacy curtain that the synthesizer acted as on the studio version was still there.

—

Chan Marshall didn’t make WHAT WOULD THE COMMUNITY WANT for my personal enjoyment, or anyone else’s. Nor did she make it to advance her music career as Cat Power, or to achieve material wealth or fame. She wrote it and recorded this album for herself-not because believed in the toxic idea that the only “real” art comes from pain and suffering-but because her very real pain and suffering had nowhere else to go but into her music. The way that Jeff Tweedy once put it in a TV interview is that the “damaging mythology” of the troubled artist has it all completely backward: rather than buying into the idea that his pain was what inspired his great works from the past, “I look at it like the part of me that was able to create, managed to create in spite of the problems that I was having… almost as if that was the only healthy part of me.” Marshall made this album not because of her pain, but in spite of it, and the fact that the results are still so thrilling to listen to 25 years later is only a testament to her singular talent. Rather than giving the demons and struggles of these tortured artists the credit for the great works they created while suffering, we should marvel at the fact that art born out of such difficult circumstances was able to be created at all.

My favorite song from Cat Power’s fifth album, YOU ARE FREE, is a song called “I Don’t Blame You,” a piano ballad that she later revealed was written about Kurt Cobain. The song dedicated to him ends:

“Then you would recall the deadly houses you grew up in

Just because they know your name

Doesn’t mean they know from where you came

What a sad trick you thought that you had to play

But I don’t blame you

They never owned it

And you never owed it to them anyways

I don’t blame you

I don’t blame you”

I will never be able to know exactly what it’s like to be Chan Marshall, to live the life she has lived. To grow up in a house torn apart by alcohol, psychological illness and divorce, or to suffer through years of intense depression and anxiety while having to perform and create for an audience. I’ll never know what it was like to be Mac Miller, to be Kurt Cobain, to be a human being living your life at the intersection of immense talent, expectations, and personal struggles, and having to go through it all in the public spotlight.

But that’s what music is so uniquely capable of doing: it allows us to use this shared artistic language as a way to connect with other people and better understand emotions and experiences that are not our own. WHAT WOULD THE COMMUNITY THINK reveals an understanding of Marshall and her life from a time that is impossible to glean from reading an article or biography written about her. It’s something that can only be communicated through the specific universality of music, and the way it makes us feel and captures what makes us human. Even though my experience is different from hers in a number of dramatic ways, there is so much about this album that speaks to me, so much that I can latch onto from my own experiences of being a very mixed-up young woman. I am incredibly grateful to Marshall for having created this album. Even though I’m sure it’s at least a little painful for her to listen to these songs 25 years later, I hope she feels grateful too.

What a fantastic write-up, I really enjoyed reading it.