Before I was the music fan I am now, when I was instead known as one of the resident film buffs at my high school, I wrote a massive report on Bob Dylan. It was ostensibly my senior research paper, though it was in an honors English class my junior year—a group paper deep diving into a subject, with a broad thesis and carefully detailed MLA citations. Basically, the kind of thing kids are no doubt scamming their way through with ChatGPT now. Countless hours reading about Dylan’s early life, watching Scorsese’s NO DIRECTION HOME in our school library, pulling all-nighters with his music on in the background… It’s the kind of thing I would likely relish now, but felt like genuine work then.

If memory serves, we got a B- on that paper, which was fine for me because the paper basically doubled as your final grade in the class. But that grade was due to a few factors; our teacher, Mrs. Miller (a formative influence on my writing and someone I credit for getting me to pass college), was an old hippie type—while others in the class were writing about the Roman Empire we picked a subject she’d been smoking pot to during his heyday. Our actual group was a mix of remarkably gifted but lazy students and one kid who was a genuine nerd and thus seemed like he belonged in an honors class, but was actually kinda dumb. Likely the biggest reason we got a B- though was that, frankly, our thesis was not particularly strong. We blindly tried to frame perhaps the most important cultural voice in American music through a historical lens, trying to chart what we knew about his youth into eventual world events like Vietnam, the JFK assassination, the Civil Rights Movement, etc.

B-

I wish I had a copy of the paper. It was this massive 100 page beast that we only barely scraped by turning in. And in retrospect, it’s not that the framing was bad, per se, it was that to sum up Dylan through history, either his own largely self-created mythology or that of America and the world’s, is almost reductive to his actual brilliance as a songwriter and artist. ”I don’t know how I got to write those songs,” he said in a rare 2004 interview with 60 MINUTES. “Those early songs were almost magically written.”

The idea of a straight Dylan biopic like A COMPLETE UNKNOWN always seemed similarly reductive to me, for all the same reasons I still think five high schoolers trying to write a research paper on that early period was misguided. James Mangold is no stranger to the rockstar story, but of course the box office success and award prestige of both his 2005 Johnny Cash biopic, WALK THE LINE, as well as the previous year’s Ray Charles picture, RAY, led to two decades of studios grasping at straws and finding derivative music stories with similar beats. Were your parents abusive? Were you the voice of a generation? Did you do drugs? Did you get sober? Did you play a big, defining concert? Rinse, repeat.

A COMPLETE UNKNOWN is, in many ways, a best case scenario. Mangold co-wrote the script with occasional Scorsese collaborator Jay Cocks using the book Dylan Goes Electric! by Elijah Wald to help frame it. It opens on Dylan’s move to New York City in 1961 and concludes shortly after the moment he plugs his guitar into an amp at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965. While this is arguably the most detailed and well known part of Dylan’s life, I can understand the appeal of making an origin story—if the idea of Bob Dylan needs to be captured on film for a multimillion dollar movie, both his ever evolving persona and the genius of the music are probably best served by trying to start with the cultural familiarity of the beginning.

In this way, Mangold has accidentally made a good film. In all the ways that Todd Haynes’ 2007 picture I’M NOT THERE is obsessed with Dylan’s own mystique and mythmaking, Mangold’s is the total opposite; A COMPLETE UNKNOWN is incurious and straightforward filmmaking, presenting supposed facts in linear fashion—perhaps frustratingly so. At one point, Sylvie (Elle Fanning), our standin for Dylan’s former partner Suze Rotolo, pulls at that very unexplored thesis, yelling “You came here with nothing but a guitar, you never talk about your family, your past!” only for Dylan to retort “People make up their past, Sylvie, they remember what they want and they forget the rest.” Books have been published, articles written, podcasts recorded, and in Haynes’ case, movies filmed, about the idea central to that exchange as it relates to the question of who exactly Dylan is. But Mangold can’t be bothered. The script focuses on highlighting Dylan’s strange genius through his “magically written” songs alone, and inadvertently this allows Dylan’s own persona to become even a mystery to us if by sheer filmic neglect.

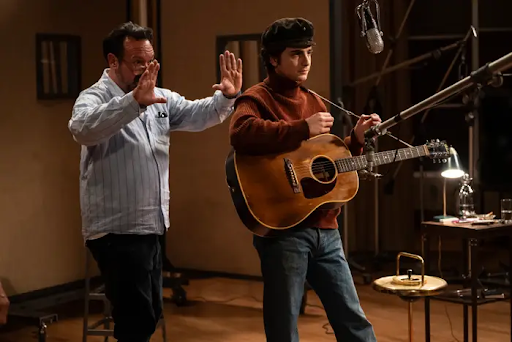

Once this narrow framing of Dylan is revealed, you sense that the ceiling for this film isn’t particularly high—what could be said here that hasn’t been said elsewhere hundreds of times in discussing Dylan? Is the idea of his origin story, told so plainly, actually that interesting? And yet, A COMPLETE UNKNOWN is doing all of the little things so well that it hits that ceiling with gusto, centrally nailing the performances. The concept of someone doing a Bob Dylan impression for two hours is such a dangerous proposition that Timothée Chalamet’s acting alone makes the film a marvel, never veering into caricature despite how easily parodied the voice is. The performance is subtle and well studied—you might be able to hear something more comically nuanced when James Austin Johnson does it on SNL, but what Chalamet nails is a remarkable groundedness that saves the film.

And that’s to say nothing about the musical performances which, while straight laced, are their own marvel due to the tightrope walk of the actors actually singing and playing their own instruments; Chalamet’s live guitar and harmonica are remarkable for an actor, but there are delightful moments with Monica Barbaro’s Joan Baez, Boyd Holbrook’s Johnny Cash, and Edward Norton’s Pete Seeger, each equally impressive in their own ways. The film’s best scene features a jam between Seeger, Dylan, and a fictional bluesman named Jesse Moffette, played by Muddy Waters’ son Big Bill Morganfield—a by all accounts entirely made up public access performance that is as gripping as the film gets. Ultimately, if A COMPLETE UNKNOWN succeeds, it’s because these musical moments are undeniable. Dylan is, perhaps, one of the rare musicians where just letting us hear and see the songs written and performed unlocks a level of character building that no proper script could with that level of quiet understanding; Mangold might be incurious, but he knows the music is powerful enough to carry him. Even if it leaves the film feeling a bit hollow, damn if seeing “Like A Rolling Stone” played live doesn’t hit—you’re simply not getting that by watching an actor pretend to be young Mick Jagger and sing “Start Me Up.”

I’m interested, ultimately, in what the non-Dylan fan will think of this movie, because it isn’t some kind of heady character study. It draws few conclusions about who he really is other than being a virtuosic eccentric. Is he brave for going electric? What became of his relationship with Joan Baez? Had he actually soured on the folk movement, or was his music evolution circumstantial? Where did those songs come from? A COMPLETE UNKNOWN doesn’t want to answer those questions—that’s ultimately for B- High School research papers to try and do.

Comments