I’ve always wanted to love James Gray. It’d make my life so much easier if I could join the cushy cinephile crowd that heralds him as one of our living greatest, but the warmed-over Coppola riffs never griddled my loins. The adulation hit its peak boil upon the rave release of THE IMMIGRANT, a film seemingly forgotten and only recently recalled for the odd inclusion in a best of the 2010s list here and there. But it’s a film indicative of his secret sauce. No one’s making ‘em like James Gray does—not in that he’s reinventing the reel (far from it), but in his continued resurrection of a bygone flavor of epic American cinema, where sky was the limit for production and artistic, jurisdictional pomp. How he keeps getting major budgets after a history of low-profit returns confounds me, but thank goodness directors who genuinely care for the medium are given multiple chances—otherwise, they’d be deterred from eventually making their greatest work. Enter AD ASTRA.

Welcome to the Moon…. Don’t mind the killer pirates

AD ASTRA is an airplane novel premise stretched to the vacuous ends of the galaxy, expanded enough to watch every neuron fail to deliver a dopamine rush to Brad Pitt’s Roy McBride, a clinically depressed astronaut living life one turn of the screw at a time. Sent to the outer reaches to recover his father lost in space, 79 days in orbit with your own mind as sole company is scarier than any extraterrestrial threat. Pitt is fantastic, his sunken eyes transfixing our gaze into his pupils, these emotional bullseyes you can’t pull away from. Who would’ve thought Brad fucking Pitt would age into Tommy Lee Jones’ cavernous sockets? His Roy McBride is walking in a vacant body, those cratered peepers always on the exit and lauded by SpaceCom for his famous father and a calm heartbeat that never exceeds 80 bpm, even under duress. It’s a Steven Seagal character, but approached with the interior desolation of a meticulously erected space vessel. It’s no surprise that Pitt continues his run as one of America’s finest actors, but watching Tommy Lee Jones actually give a shit is mesmerizing. It’s an all-consuming, yet never loud, performance that urges a complete viewing of a filmography.

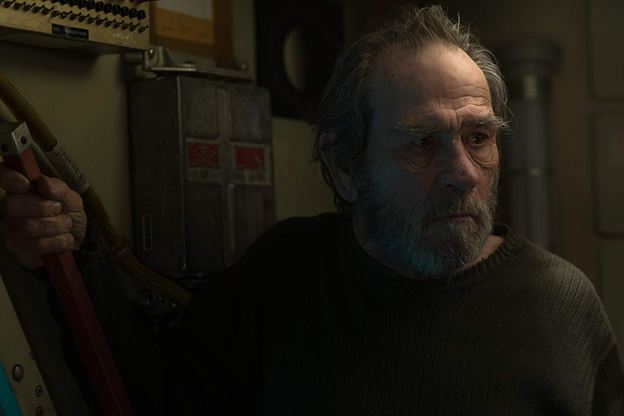

God, I hope he isn’t a Republican, I really greased his goose

In 2019, Brad Pitt stood his own against Bruce Lee and catapulted himself through Saturn’s rings and yet The Rock is still considered the greater adventure star? Phooey. Just as Pitt is the unspoken Harrison Ford of our era, Gray somehow cemented himself as the master of the car chase. The Moon rover pirate pursuit is both completely unexpected and astonishingly assured spectacle—WE OWN THE NIGHT’s downpour-splattered mob chase is still his claim to fame, but AD ASTRA is a glib reminder that, if Gray wanted, he could use his resources to make a rollicking studio picture; it’s not outside his wheelhouse. It just isn’t what interests him.

Disjointed, episodic structure with stops and starts as harsh as the transitions between stages of psychological rehabilitation, AD ASTRA carries on Gray’s preferred theme of vocation as vacation; a regimen of concentrated tasks seen as more effective antidepressants than outright confrontation with the demons lingering in your second-to-second experience. That is, until the latter takes on the truth of the former. Roy goes through confidantes like rotating caretakers, bidding bitter farewells to warm faces as he’s wheeled on to the next handler. A mayday call utilizes verticality of space for tension, but botches the punchline with a couple CGI primates that are somehow more heavy-handed than when Clare Denis crafted the same motif earlier this year with HIGH LIFE’s ship of abandoned dogs. Once we arrive on Mars, the sets shift from hyper-real aluminum walls to a Terry Gilliam world—every moment is disparate, linked together by the bottomless despair of the subconscious as Pitt reckons with the memory of his father amidst the consequences of his actions like it were Moby Dick. Whether you allow yourself to give in to this near-comically unfiltered pit of emotion will determine whether AD ASTRA becomes the most affecting or most irritating film of 2019.

The Temptation of the Leap

What I’m still trying to parse out is how I dislike James Gray’s oeuvre, yet love AD ASTRA, a film that’s maybe the Grayest of the Grays. I suppose it’s a case of The Amy Adams. I’ve gotten into hot water numerous times for my thoughts on Amy Adams—namely, I can’t imagine a greater chore than watching her perform. I know, I know, yikes, I’m sorry, but there’s no other actor who acts quite as hard as Adams does. In intimate moments, she invokes performance, and in scene-stealing beats, she wears a blank face, neither of which have ever lent themselves to the stories being told. It’s why her shining hour is AMERICAN HUSTLE (oh my God, remember AMERICAN HUSTLE?), a role that explicitly positions her as a bit-rate performer cracking at the seams. The actor’s ability ionically bonds with the film’s vision, it’s a Casper Van Dien-in-STARSHIP TROOPERS revelation. James Gray finds himself at a similar watershed moment. Each of James Gray’s films are its own SparkNotes booklet, chock-full of pre-digested bile that render any post-screening analysis redundant—his films are their own C+ book reports on themselves. At one point, Pitt declares that “in the end, the son suffers the sins of the father.” I can’t remember if that’s said after or before someone groans “You’re so distant.”

Hitched to AD ASTRA is what’s being called an atrocious voice-over, and the critiques are not off-base—Pitt narrates the film with achingly obvious asides, the angst bleeding through the waveforms. The voice-over is painfully bad, and yet that’s what makes it so fantastic. It legitimately feels like a man attempting to struggle with his emotions for the first time ever. Ask the poor ex-girlfriend-turned-therapist you wept to in stuttered sentences on late nights to run back what she had to sit through and you’d more or less have Pitt’s exact transcript. Even if this read doesn’t sustain your full 120-minute experience, we can at least agree that everyone has had the same soul-sucking inner monologue whilst thrust through the profound emptiness of commercial airfare. The Moon is inhabitable and borderless, but our species still split it into factions. Our species invented interplanetary travel only to put an Applebee’s on the Moon. As Roy narrates, “We are world eaters.” Blankets may not cost hundreds of dollars, but you’re still charged hundreds of dollars for the service of moving oneself from one place… To another. Oh, apparently Liv Tyler and Ruth Negga are in this? I honestly couldn’t tell you; they may as well have been cut out, it’s a shame.

Talking Into A Microphone To No Listeners: The Therapy of Having Your Own Podcast

Pitt’s final lines are meant to inspire hope. However, notice that his tone hasn’t changed, nor his morose timbre—for some, redefining a life of pain to focus on living and loving is a switch, but for many, it’s submissive resignation. With sights and sounds as seismic as what Gray accomplishes, AD ASTRA unfairly positions itself as an event film, a positioning that’s inspired quite the polarizing reaction with mass audiences, but the naked emotion lends itself better to a singular, blanket-wrapped viewing. Before you can tearfully evaluate the suppression of all meaningful feeling with the bros, you gotta sit beside yourself, am I right or am I right, fellas? It is in the gentle poetry of AD ASTRA that both director and muse find that, after chasing their idols for decades, it is the pursuit of one’s own voice that yields the finest fruit.

A beautiful appraisal. I felt just as caught between irritation, satisfaction, and full on surrender. You gotta admit though, after what McBride did he shoulda been delivering that final monologue from a prison cell.

Thank you so much, Michael!

Totally agree, McBride’s got…. what, around 15 bodies to his name by the journey’s end? hahaha a literal prison evades him, but….. THE MENTAL PRISON OF EMOTIONAL TRANSITION RAGES ON!!!!!