This article previously appeared on Crossfader

Most of my energy these days is dedicated to maybe thinking a little too hard about movies (and trying to land a Big Boy Job, but hey), but, like many ‘90s kids, there was a time when my entire life revolved around the vidya. I was so fortunate to grow up alongside so many rapidly evolving forms of entertainment during that technological Big Bang. It may sound extremely lame, I know, but looking back I can’t help but think to Hunter Thompson’s “Wave Speech.” But, even so, I wasn’t always moving from one title to the next. It was pretty uncommon for me to find a game I truly cared about. When I did, though—whew! You couldn’t pull me away. To that, one of the very first games to fully command my attention—one which captivates me to this day—was METAL GEAR SOLID.

The set-up is simple enough: a legendary soldier is sent on a top-secret mission to free hostages and prevent a nuclear launch from a weapons facility that has been captured by a rogue special forces unit. However, our protagonist, Solid Snake (no hero, never was), soon realizes that he hasn’t been completely clued in.

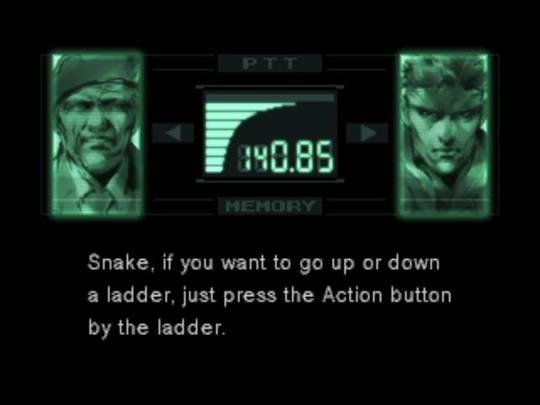

Things get real weird, real quick. What is initially presented as a straightforward story then gets broken up by long dialogues on genetic and evolutionary theory, nuclear proliferation, the Cold War and various other geopolitical conflicts, between run-ins with a Russian cowboy, a psychic gimp, and a no-shit, robot dinosaur. A story which—spoilers for a 20 year old game—culminates with Snake hashing out a Freudian beef with his clone brother/Jungian Shadow via fist fight to the death as stealth bombers close in on them.

There’s also quite a bit of this

METAL GEAR SOLID has, if I haven’t made it clear, a lot going on. When you get right down to it, it’s almost as if a Japanese game designer with a polymathic affinity for Western pop-culture—and an adolescent’s appreciation of context—decided to jam all of his interests into one project. The game pits realpolitik discourse and hard sci-fi against poop jokes and panty shots, within a story that is at once a barely-coherent spy thriller, a deadly self-serious and comically absurd drama, and an unironic love letter to the macho, bicep-worshipping glory days of 1980s action films. It’s wild. But, even if the game doesn’t always make sense, it is a testament to Kojima’s brilliance as a designer that he made every disparate, contradictory, bizarro element he put into it work. That they worked in ways no one would have never expected is its genius.

At face value, METAL GEAR SOLID is ostensibly an action game. However, the old “shoot first, ask questions later” doesn’t really work. Kojima—who is quite vocal about his anti-war, anti-nuke beliefs—went to unprecedented lengths to dissuade players from actually engaging the enemy. The most obvious example of this is the game’s alert system: being seen or even leaving footprints—lord forbid you fire a weapon—will almost always alert enemy soldiers, often causing more of them to close in on the player’s location. If the player kills any of them, more heavily-armed soldiers will take their place. So on and so forth until Snake is neck-deep in the shit.

On the other hand, knocking out or simply sneaking past a guard can save a lot of grief. In retrospect, the subtitle “Tactical Espionage Action” should have been a pretty clear giveaway, but I’d be damned if you could point to anyone who knew or cared what those words meant in ‘98. After all, the concept of “stealth” action just did not exist outside of the previous “Metal Gear” titles, and those did not even begin to approach the complexity of METAL GEAR SOLID.

Snake doing some wet work

Of course, moralising in video games is pretty commonplace these days, but games used to be a lot simpler: shoot the bad(?) guy, move forward, shoot more bad guys, eventually beat the game. There wasn’t a whole lot of room for philosophizing, is what I’m saying. Then METAL GEAR SOLID came along, proposing the radical idea that you probably shouldn’t kill people. It was also the first to suggest that media that could train youth to act as soldiers might not be a good thing. And that part really is important.

If video games do one thing, it’s reinforce specific behaviors—give a character a gun and you can bet it will be fired at the next thing that pops up on the screen. No one (save for a gaggle of concerned, yet clueless and way overzealous parents and politicians) had ever given a second thought to that. Kojima did, though, and he saw the danger of it in an increasingly technologically-driven world where traditional political lines were rapidly shifting and blurring. So, he encouraged players—would-be soldiers—to stop and think, to consider the consequences of their actions, and to solve problems without resorting to violence. It was a simple trick, and one which literally redefined action gaming.

But let’s be real for a minute here. Even though I grew up gaming with the best of ‘em, my childhood was really shaped by all the Hard R movies my wildly irresponsible parents let me watch. Who would have guessed that Kojima was inspired by those very same films? And that they would play such a pivotal role in the creation of one of the greatest games of all time? The most famous example of this is Solid Snake himself, whose character design was based upon Kurt Russell’s iconic Snake Plissken in 1981’s ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK (not to mention the name, or the whole lone soldier sent to rescue a hostage from an enemy-controlled island thing). There’s also Snake’s commander and old friend, Colonel Roy Campbell, who was lifted directly from that of Colonel Sam Trautman, John Rambo’s mentor and former CO as seen in FIRST BLOOD. And who could forget Revolver Ocelot, the aforementioned Russian cowboy/torture enthusiast/triple agent, who was partly inspired by Lee Van Cleef’s character Angel Eyes in THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY?

Seriously, everything is a reference

But Kojima’s love of cinema extended far beyond mere character design; he managed to pack references to one film or another into just about every aspect of the game. There are several nods to the landmark action films of John McTiernan alone. From the optic camouflage utilized by Cyborg Ninja to Vulcan Raven’s awfully familiar gatling gun, METAL GEAR SOLID positively bleeds PREDATOR. On top of that is Snake’s encounter with an attack helicopter which leads to his narrowly avoiding a rooftop explosion, à la DIE HARD. And then there are the frequent, albeit more esoteric references to other classics such as Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY, Katsuhiro Otomo’s AKIRA, and David Lynch’s BLUE VELVET. But the director who influenced Kojima more than anyone else? None other than Alfred Hitchcock.

Hitchcock was a pioneer. He transformed the camera into the eye of the viewer, making them voyeurs to, but also active participants (so-to-speak) in, the events unfolding on the screen. This, along with the way he framed shots to heighten their sense of tension and dread, earned him the nickname “The Master of Suspense.”

Kojima took those techniques and ran with them. He directed METAL GEAR SOLID in the truest sense of the word, utilizing the PlayStation’s 3D capabilities in ways no one had even dreamt of. Like Hitchcock, he used the camera to play with perspective, frequently shifting between first-, third-person, and claustrophobic fixed angles, creating a more visceral, fully-realized connection between player and character while ratcheting up the stakes of the game. One of my less fond memories of the game is how damn confusing and frustrating those switch-ups were at the time. Sneaking around was a total nail-biter, and the battles I would inevitably get into after accidentally moving the wrong direction were that much hairier because of it. Who said infiltrating a nuclear base should be easy, anyway?

Thanks for the memories

I’m running the risk of going as long as one of the game’s cutscenes here, but it would be too easy to just call the game a masterpiece or to say that Kojima revolutionized gaming. (I haven’t even talked about Psycho Mantis!) Depending on how one looks at it, with its intricate storyline and ruminations on fate and self-determination gradually revealed through lengthy voice-acted cutscenes and the innovative use of the PlayStation’s hardware to enhance its emotive power, Kojima either built a film into his game, or he designed the game around a film. The result was nothing less than the first video game to assert itself as more than just a game—as a rightful work of art. METAL GEAR SOLID was the first cinematic video game, a legacy that has been—and will continue to be—felt in every game released after it.

Comments