“Although I have a tremendous amount of respect for Alfred Hitchcock, who is the true master of horror and the father of much modern filmmaking technique, I don’t actually wear a suit as a tribute to him. Believe it or not, I wear a suit and tie as a sign of respect to the cast and crew. I like a very serious and well ordered film set—for me it’s the best way to work, and out of that order I like to get a tremendous amount of creativity. And at the same time, the old master used to dress in a very formal manner on set, and I always thought that it was supercool. Nowadays everyone’s got the nose rings and the colored hair, so for me to wear the suit and tie is a different way to go.” – Sam Raimi, 2004

Who spearheaded the affection for Sam Raimi if not for the nose-pierced, colored-hair freaks? The pride of Michigan and the king of the live-action cartoon, his signature mid-century attire—tucked dress shirt, tie, blazer, and (if he’s feeling frisky) a fedora—is in stark contrast with the stylings that have made him a familiar name: mania, slapstick, reverential histrionics, and a surgical control of all three. In fact, his formalist patterns are as uniform as his working regalia. The same strengths accompany similar weaknesses throughout Raimi’s 40-year-long career, only differentiating in how well the pitfalls can be veiled by a surprise whip pan. Even his face is antithetical to his spirit! Sam Raimi looks like he could be your physician, not one of the 25 most influential filmmakers of the last 50 years, and certainly not like one of the godfathers of horror.

The suit is also implicitly worn as a show of respect to audiences; funny considering how many of his signatures revolve around gleeful disregard for viewer expectations of film decorum. That his narratives are so welcoming while indulging in paradoxes is one of the funniest aspects of his macabre machinations—he crafts subversive entertainment that’s just democratic enough that you barely notice the bruises on your arms, legs, and neck from the invisible demolition derby of Raimi. To put it as plainly as possible, Sam Raimi makes movies that register at the same pitch for normies *and* weirdos. That’s odd! For most of the 2000s, the SPIDER-MAN trilogy was the most popular conception of an American movie; it wasn’t until THE DARK KNIGHT caused a pivot to “all media is THE WIRE, but with IP” and the MCU signaled a humor shift to “all media is written like a Flo from Progressive ad” that I noticed this trilogy get labeled as “camp.” These were just the movies, and Sam Raimi was an architect of the nation’s entertainment id. So let’s break down that id in order of least feeling like it was made by a dude in a suit to most, in a show of ball-busting love for one of my all-time favorite directors. It’s somehow too early to sense what Raimi’s evolution amounts to, and hopefully by the time we reach the end of the list, we’ve both been granted a better understanding of where he’s been and how he’s dressing.

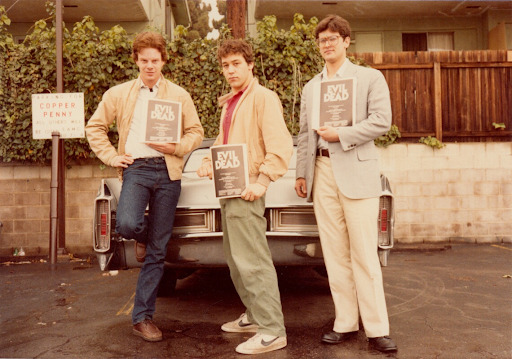

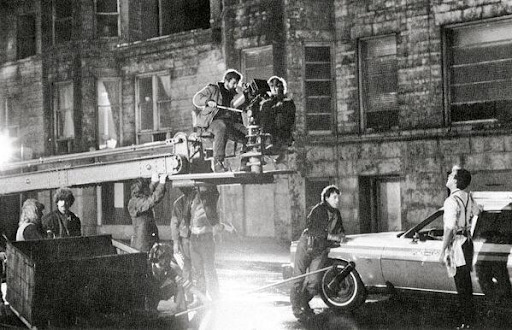

THE EVIL DEAD (1981)

In THE EVIL DEAD’s opening minutes, you can’t unsee the first-person demon POV as a couple of kids corkscrewing a camera on the wooded offshoot of a residential road. College-aged crew members can be spotted on the periphery of the frame, camera operators in window reflections, and the film stock is so bleary that you’d think non-dairy creamer was poured directly into your orbital-cavities. And then a woman gets raped by a tree. Soon after, 35 minutes into the picture, we see the victim possessed, but only after she predicts the order of a deck of playing cards from across the room. Abruptly, you’ve gone from watching low-budget shlock to maybe the scariest film ever made, a film that recreates young love with the sole motive of snatching it away as violently as possible. THE EVIL DEAD trilogy would swiftly position Ash’s anguish as physical humiliation, but his first outing is one primal lashing on his psychology after the next. His friends, girlfriend, and sister don’t just get murdered; they are gutted, mutilated beyond recognition, and manipulated as giddy husks of mental torment. A Deadite, the name that’s come to describe THE EVIL DEAD’s rotting Hellspawn, is perhaps the greatest movie monster, these wretched vessels of anti-humanity who can weaponize what you adore most for the gushiest returns. A cackling Ellen Sandweiss, eyes rolled back into her bleeding skull and aqua-blue veins protruding from rippling, concrete-colored skin, is my perfect vision of the netherworld. There’s no make-up or visual effects here—20-year-old Sam Raimi summoned a demon. THE EVIL DEAD is vile, it’s unrelenting, it’s, well, evil.

Gore wasn’t brand new, but Romero had only shocked the masses with colored carnage three years prior to THE EVIL DEAD’s release. Otherwise, leave it to maestros Fulci and Argento to satisfy the bloodlust of a curious cinematheque. Much is celebrated over the Hitchockian tendency to source scares from the unknown—it would explain the bloodless HALLOWEEN’s astronomical ascendency—but Raimi’s insistence on making you watch a Deadite of a man’s girlfriend bite her own detained hand off so she can stab him with a ritual blade is the act of a devilish provocateur. That she vomits up a milky discharge and returns with even less of a recognizable, decomposed face just to get chopped to bits by the boyfriend is proof of a madman behind the camera. In Reagan’s America? How dare you, heathen. Sam Raimi never dipped his toes into political cinema, his preferences of sideshow attractions and vaudevillian flights taking precedence over using the cinema as a transport for ideology, but THE EVIL DEAD is some of the closest you’ll get to total screen anarchy.

This is what moviegoing is all about: a ghoul’s melting face will make you inhale the breath of a theater patron nine rows away, while collectivizing a near century’s worth of independent efforts to best utilize the medium. Spilled blood as a choreographed expression of Busby Berkeley-esque butchery. Why? For the sake of it. Once you prove a movie like this can be made, there’s no going back. Kill her if you can, loverboy. Raimi’s storied career is abound with episodes of arranged chaos, but you only get to blast off with red-blooded enthusiasm, unapologetic heartlessness, and the capacity to be forgiven by your abused 20-something friends in the name of artistic endeavors like this once. It’s a feral dog biting off its own tail in the kennel, surrounded by the bloodied pelts of other poor canines placed in the cage by those who knew no better. Most of us waste this aggressive vigor, and some of us are Sam Raimi.

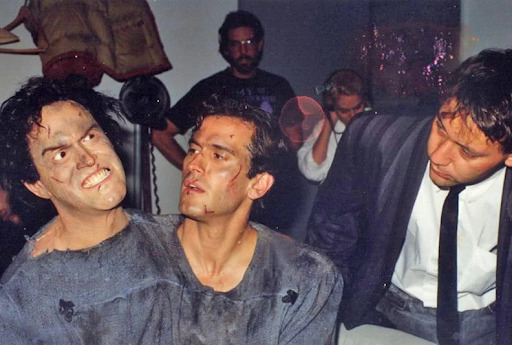

EVIL DEAD 2 (1987)

When film geek twerps have nothing but focus in their inventory

They will do violence.

You don’t need more writing on EVIL DEAD 2.

You just need to watch it again.

SPIDER-MAN (2002)

Peter’s bite is bulbous: SPIDER-MAN takes great restraint in not making the wound pop with pus. Raimi makes up the difference by turning the web-slinging and hair-rising spider-sense into matters of gross anatomical phenomena. SPIDER-MAN isn’t as interested in superpowers as it is mutations of the body and spirit. Norman Osborne succumbs to the inferiority complex of being deemed a genius in a corporate power structure, and Peter Parker goes from having to get by to seeing it within himself to allow his neighbors a fair fighting ground. There’s taxes, deaths in the family, and missing the bus to worry about. Leave it to Spider-Man to handle Green Goblin in between third period and homeroom. Raimi’s greatest blockbuster is both perfect entertainment and an all-encompassing amalgam of every single film and gag he’d cooked up to this point. It’s all of him in one motion picture, so confidently collected that I could see Raimi in either a black turtleneck or a Zoot suit making it. The result is the platonic ideal of the American popcorn film.

Willem Dafoe screeching at Rosemary Harris to finish her prayer as fire engulfs her bedroom is villainy for the ages. Green Goblin’s subsequent fatal impaling—gruesome and gory—is intrinsic to Sam Raimi’s most dastardly trick: as lovingly conventional as he strives his cinema to be, he sneaks the jabs that bruise longest with moments that go further than you were expecting, be they silly, sorrowful, or grisly. In many cases, such as here, that acceleration dips into the rollicking sentimentality of American comic books. The sincerity with which Peter recalls crying to MJ’s Cinderella performance in the first grade feels like Raimi blasting through David Koepp’s poppy screenplay to present his raison d’être. The core memories of our childhood are as valid in middle age, adolescence, or senile seniority as they were when they first popped neuron receptors. Peter dresses up as a spider to protect your personal Uncle Ben, MJ falls in love with the first protector she’s ever known. Some may call it arrested development, and it’s certainly what the mass media landscape gleaned the most from SPIDER-MAN, but the trilogy never stopped insisting on the possibility of purity, even when engaged in day-to-day systems that tear us apart.

A SIMPLE PLAN (1998)

There’s a pivotal scene in A SIMPLE PLAN where an enraged Lou (Brent Briscoe) aims a shotgun at the brothers on his porch who’ve conspired against him to keep his share of $4.4 million. Like most of Raimi’s grounded Minnesota thriller, the tension couldn’t even be cut with obsidian. The film has proven that anyone can die, and, in the pursuit of Benjamin Franklin, anyone will die. Jacob, a career-best Billy Bob Thornton, takes aim at the man threatening his brother and begs him to de-escalate, to not act on his aggression. You can hear the genuine pain in his cracking voice. It doesn’t do much. Lou gets louder. Jacob fires off a round into his neck. Great, another corpse for the to-do list. A SIMPLE PLAN was the last major Raimi blindspot on my never-ending watchlist; he’s the horror guy, so why would I ever want to invest in the one muted crime-thriller he made. I got around to it just earlier this month, and this shotgun stand-off immediately reminded me of the recorded murder of Chad Read in Lubbock, Texas over a child custody dispute back in November. The two men, only one armed, scuffle on the porch of William ‘Kyle’ Carruth and the tussling is enough for Kyle to justify opening fire on Chad, killing a father in front of his family. It’s one of the most fucking insane videos I’ve ever seen. Carruth murders a man in front of multiple people, and they all treat the scene as if someone knocked over a wedding cake. There’s an underlying normalization of violence that tinges the Christian-American inklings for honorable principles and peace for all, and it’s an undercurrent that, while certainly tapped into over and over in fiction, has rarely been portrayed as bluntly as in Sam Raimi’s A SIMPLE PLAN.

Restrained, if over-corrected, Paramount monitoring a filmmaker who has the self-control to manage himself under the circumstances, A SIMPLE PLAN sees Raimi deprive himself of his toolbox to instead play the role of a suited master. It’s him proving he’s made of the sternest stuff, while never relinquishing the viscera of his trademarks. See how he stages violence from afar: Billy Bob Thornton puts a pistol to his temple in a startling group shot, Becky Ann Baker is blown away by a buckshot in the medium-wide shadows of her kitchen, and Tom Carey is bopped over the head in a breathtaking wide. It’s a far cry from the extreme close-ups of stop-motion-animated rot, skin dropping off faces like shredded orange peels, and yet it renders as disturbingly. A SIMPLE PLAN marks a singular moment where his constraints help us learn about the intricacies of the man– where the lines of Raimi’s moralism stop and start, and how willing he is to excuse insidious ethics as human error. He draws lines in the sand, but also pities the beleaguered. In another film, Paxton’s Hank Mitchell would be run through a series of tormenting physical trials for his misdeeds (it’s what the source novel does). Instead, he’s left totally exonerated by the law, and damned for an eternity for it. It’s one of the greatest films ever made about lonely idiots. The cherry on top is the simple plan itself. The only solution is to practice patience. Of course none of us could ever pull it off.

SPIDER-MAN 2 (2004)

The great franchises grow with their viewers, but in the measly gap between 2002 and 2004, I went from ordering a Happy Meal to ordering a Mighty Kids Meal. In other words, I matured from a kid to a slightly larger child. It took 17 years for me to watch SPIDER-MAN 2 a second time. This, PRISONER OF AZKABAN, and THE INCREDIBLES were widely considered to be “good movies,” but they were dogshit kid movies for kids who want to be entertained by the dope shit kid movies did to specifically entertain kids. I wanted something closer resembling SPIDER-MAN 3, and, well, I got SPIDER-MAN 3, and nah, that’s uh, that wasn’t really what I wanted; I’d eventually get what I was dreaming about in 2018 from Lord & Miller, and it’s still what I ultimately prefer! Sure, Raimi using the spin of diving into superhero myth via early 20s masculinity is pretty brilliant. Flunking your classes, girl of your dreams is marrying a dope astronaut, borrowing rent money from your broke elderly aunt, letting down your dead uncle, and your breaking point in all this? That white sticky icky just doesn’t spurt like it used to. This isn’t even the subtext, it’s the A-plot of one of the most influential blockbusters of the 21st century. Holy shit. Did anyone actually expect kids to follow any of this biological drama?

I’ve grown to really appreciate what this movie is going for, easily Sam Raimi’s most assured work as a company suit, but my eight-year-old brain was completely in the right to glaze over 70% of this. As much as Spider-Man is a young man caught in a crossroads between responsibility and desire, he also ultimately punches people and does tricks to beat their asses. You can make him realer than real, as Raimi cuts a vein and bleeds all over the screen to prove, but don’t dilute the lizard-brain appeal. But, God, the CGI has such an impressive tonnage. At 18-years-old, it’s objectively worse in quality than today’s company-town sweatshop PS5 cutscenes, where MCU Spidey still looks like an unfinished asset, but at least he’s surrounded by top-of-the-line particle physics. SPIDER-MAN 2 focuses its resources; every computer effect feels like a concentrated gag, rather than the very essence of the visual itself. The animation disciplines that Raimi’s distilling correspond to the humble character drama: the VFX artists are animating a dude with super powers, not a superhero. That Aunt May never knows that her nephew is Spider-Man, but still regales him as though he were a superhero? Magnificent. Though SPIDER-MAN 3 caves to a greedy villain-of-the-week bombast that persists today, Raimi’s trilogy avoids narrow hero worship by valuing the everyday lives of civilians more than the pulp exploits of comic panel weirdos. Combine this ethos with the Elfman score blasting at full capacity, and Raimi makes you believe you’re watching the most important movie in the world.

ARMY OF DARKNESS (1992)

Weirdly, it wasn’t til adulthood that I came to appreciate Raimi’s ode to “Saturday morning cartoons for kids who like to say ‘fuck’ and eat candy cigarettes.” Swashbuckling populism that betrayed the alienating vulgarity of THE EVIL DEAD and EVIL DEAD 2, I couldn’t believe how little I shielded my eyes watching an EVIL DEAD movie when I first faced off ARMY OF DARKNESS at 13. The movie franchise I hid from my parents ended its trilogy with a movie they’d bat no eyes popping on for Friday pizza night. What the fuck? I suppose it took a frigid decade of reality checks to value the classical warmth of juvenile delinquency. Campbell’s rip-roaring turn as Roddy Piper sticking his head up into Shemp Howard’s asshole is a showcase for the ages, carrying a lowkey fantasy epic on his back with the help of stop-motion skeletons and a camera that rushes his rubber face as though Raimi was trying to drone strike his jawline. A third time around the Deadite bend, and with rare moments to himself, the goofiest rendition of Ash is also the most tragic; he’s seen so much destruction that all’s left is a post-ironic veneer bandaging the internal hostility of having to decapitate his demonic girlfriend. In 2022, who can say they haven’t been there? It’s more than trust, it’s respect that Raimi has for his beloved Bruce: the title of the film is technically BRUCE CAMPBELL VS. ARMY OF DARKNESS.

ARMY OF DARKNESS is jarringly respectful of itself. This treats its lore, loosely espoused via audio logs and really only in service of garden hoses of red corn syrup, like respected ancient history. It’s such cleanly staged adventure entertainment that you almost forget that you’re experiencing a textbook flash in the pan. Let alone how ARMY OF DARKNESS statistically shouldn’t exist—a medieval hack-n-slash Universal Studios sequel to an NC-17 video nasty from 11-years prior? There’s no timeline but ours where Raimi conjures genuine sorcery to make it feel like an actual movie. And his agenda is simple: make a movie sourced from the flavors of a Renaissance Faire. ARMY OF DARKNESS is shiny sharp metal, deep-fried turkey legs, and the collective joy of playing a little dress-up. The slicker the camerawork, and the less rickety the sets for an Evil Dead movie, the more you feel like Raimi is getting away with murder. At the same token, if you can tamper with the recipe enough that it can sell to your local multiplex, then maybe you’ve sanded off more than just the blitzkrieg gore—Raimi’s progressive trajectory towards working at more massive, welcoming scales begins in earnest here, closing the loop he began with his pals in the woods with a Harryhausen romp they previously never thought themselves able to afford. ARMY OF DARKNESS is the dawn of the three-piece suit, but at the doubly same token it’s still a movie where Bruce Campbell guzzles from a boiling kettle so he can immolate the tiny Ash gremlin hiding in his tummy.

THE QUICK AND THE DEAD (1995)

Raimi’s devotion to sepia-tinged hootenanny is less him running wild as it is him delivering upon a formal politeness to the star-producer who saw his potential. The fact that THE QUICK AND THE DEAD exists because Sharon Stone immensely enjoyed ARMY OF DARKNESS is so cool that it elevates the reputation of all involved. I probably like the movie more because of that background info! This is his most simultaneously dressed down and dressed to the nines film, putting his whole essence into executing gag after gag, but also stretching his resources to treat his femme fatale as a woman of esteemed regard. The first in Raimi’s trilogy of leading women—an unfortunate rarity for a filmmaker who can direct actresses to such rich limits of camp and curiosity—bullets down the track at full steam, so much so that I forget Russell Crowe and Leonardo DiCaprio are supporting players. It’s such a fun romp, but it was destined for failure by the studio workflow curse of arriving too late to the party: in the post-UNFORGIVEN haze, TOMBSTONE, WYATT EARP, LEGENDS OF THE FALL, and MAVERICK all dropped to the tune of hundreds of millions while John Sayles was getting his revisions for THE QUICK AND THE DEAD tossed into the garbage. It was a film killed by its contemporary context of bloat that is, ironically, now celebrated as an antidote to a different species of bloat.

The picture’s a two-way rifle no matter which way you cut it, so many of its strengths paving the path for its weaknesses, and vice versa. Though we’ve blamed the tides of time on why older media fails to entertain as much as the newest, latest, and best, it’s been over 25 years and few have dared reach these stylized heights. It’s as exciting as your dad’s memory of GUNSMOKE, but also messianic to its aesthetic upheaval of the American cultural memory of westerns that it stands as prolonged parody. It’s no help that Gene Hackman, a triumph of a dastardly sheriff, is playing a pared down version of his multi-dimensional UNFORGIVEN character. He’s great either way, it’s Gene fucking Hackman, but the direct comparison puts Raimi at an unnecessary disadvantage before the camera can even be loaded with a new canister. It’s like having Adam Driver resume his portrayal of Kylo Ren on SNL, but not as a joke… okay, except, there’s a percentage of it that is a joke. It’s a bit of a mess, and THE QUICK AND THE DEAD makes no mystery where the bulk of its interests lie, every armed stand-off blowing the wheels off of each and every scene without a gun, but if rootin’n’tootin is the pleasure ye seek, here it is, baby.

DRAG ME TO HELL (2009)

To this day, we are under the false perception that filmmakers who sell out and take checks for modern superhero flicks and IP upchucks are merely collecting their pennies so they can invest in smaller, bolder, more personal projects. This does not happen. I repeat: this never fucking happens. Everyone thinks this happens because DRAG ME TO HELL happened. Just as SPIDER-MAN was the First Testament of modern pop culture zealotry, DRAG ME TO HELL is a similar foundational text to one of the most misleading myths in American filmmaking. If only it was the prevalent model of moviemaking so we could have more auteurs flying off the leash with new-age toys just as they had in their building block primes. Fresh off the SPIDER-MAN contract, Raimi’s return to his stomping grounds envisions horror as both spectacle and cringe comedy. You see a toothless witch pop gum blisters while suckling on the protagonist’s chin, but it’s somehow not as cringe-inducing as watching the heroine later ask for a cash advance on a job promotion she’s not yet been selected for. God, yikes, Jesus Christ, just typing it out is giving me full body goosebumps again. Playful, disgusting, glib, and, most importantly, always childish. The diner denouement sees a tortured soul drowning in hot fudge sundaes like they’re martinis, a joke that THE SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS MOVIE originated five years prior.

DRAG ME TO HELL is fiercely true to itself, maybe too true to itself. Raimi isn’t elevating material. He’s making a 1980s VHS ripper that could just as easily live on as a forgotten gem or another log for the heap. Ever seen James W. Roberson’s SUPERSTITION? No, right? But if you have, here’s the little moment in the article where we can rejoice over how weird it is. Would we ever recommend it to someone to watch? No, probably not, but we’re glad to have done it ourselves! That’s DRAG ME TO HELL. This is the Blumhouse model with none of the pretension of representing something bigger: is this a movie about PTSD or feminine trauma? No, this is about getting dragged to Hell. It’s traditional shlock to the point of being underserved by working actor stiffs, all too cute to elicit realism, but remarkably plain enough to bar them from their next steps. For all except Raimi himself, DRAG ME TO HELL is a bus with a single stop, including short-lived scream queen, Alison Lohman. Christine Brown is the perfect moral analogue to SPIDER-MAN, with Lohman doing Tobey Maguire if he never put on the super-suit. She offers up her body to the cinema in the most Campbell-ian fashion, getting thrashed about for any jolt possible. Her dedication to the bit outweighs her unfortunate lack of screen presence, Raimi propelling her in moments of otherworldly physicality and, perhaps, failing her when it comes time to carry a movie on her back. When Wanda Maximoff’s nightmares are simply Raimi putting Elizabeth Olsen through a quick DRAG ME TO HELL recreation, it’s tough not to appreciate the performative fear an actress of her caliber is able to modulate: she’s not scared for her life, she’s scared of what the movie is doing to her. It’s an incredibly specific performance style, and one she excels in. But would Elizabeth Olsen be game to take firehoses of goo right to the dome, or have a full wig’s worth of hair ripped from her scalp.

The meanness comes in the form of the film’s extreme moralism: DRAG ME TO HELL thinks so lowly of its protagonist, a stooge in the cogs of big bank America whose complicity is as criminal as the overseeing by any nine figure earning creep of Jeffrey Epstein’s offshore accounts. Christine chose a big girl career to to recoup her parental losses and, unbeknownst to her, signed a blood oath with greed. There’s little room for forgiveness here. It’s a movie about getting sent to the spookiest gulag. Raimi holds back from spilling the human offal one would’ve thought he’d unleash when able to work with no overseers—disappointingly, it’s definitely a PG-13 horror movie, but he zeroes in like a missile for his once-a-decade foray into his personal worldview on the definition of evil. Satan and a loan officer deserve one another.

THE GIFT (2000)

At first, THE GIFT feels like outlier Raimi—such classical, theatrical character examinations for an ensemble to gorge on, and so little of his trickery that can obscure them—but makes total sense as a tale told in the neighboring woodland towns of THE EVIL DEAD’s cabin, Deadite influence spilling into the mossy water supply rather than in the form of taunting, homicidal corpses. Cate Blanchett walks away with the picture as a medium who professionally offers premonitions in her own living room to put food on the table. That she’s a psychic bears no effect on the threats of violence hurled into her fragile domestic sphere. You could extract the supernatural elements of Billy Bob Thornton and Tom Epperson’s generous screenplay and their conceived world’s hostility towards independent women would still pervade in the thick, humid air. When I popped this on, I didn’t expect a top three Blanchett performance, I didn’t expect Katie Holmes’ titties, and I absolutely did not expect Giovanni Ribisi to get second billed in the credits *before* a slur-slanging Keanu Reeves. It tees itself up as a sumptuous post-A SIMPLE PLAN slice of southern-fried America, as Raimi’s very own EATEN ALIVE, but THE GIFT aims for so much that it doesn’t really excel at any of its targets. For what he sacrifices in sustaining his usual drilled authority over the narrative, opting for a lackadaisical mix of patient character rumination and hackneyed murder-mystery antics, Raimi still achieves some sicko, if hollow, entertainment that would’ve been the formula for an Emmy-dominating HBO series had he held onto it for 15 years; instead, we got a completely forgotten early 00s thriller that now exists so people can call it “underrated, actually.” There are worse fates, but there are also better!

SPIDER-MAN 3 (2007)

The first SPIDER-MAN expanded to not one, but, count ’em, two whole boroughs of New York City, and centered itself on seven whole characters, one of which is killed off before the second act. I think there are seven speaking parts alone in the first four minutes of SPIDER-MAN 3. Gorged enough to clearly then be the most expensive American film ever made, and constricted by enough screenwriting lard to disprove any notion that money buys talent, SPIDER-MAN 3 is the ugly duckling of the Raimi SPIDER-MAN run that, unfortunately, deserves most of its ridicule. Mary-Jane’s been aged down, Harry might as well have not even been in the previous film, and Peter’s stuck in perpetual adolescence despite shedding the structure of his former life; meteorites randomly crash into Earth, newly introduced blonde cohorts suddenly become more important than Aunt May, and there’s an amnesia subplot for good measure. It’s senseless cartoon logic after asking audiences to treat these stories as legitimate, human ones.

It’d be one thing if Raimi wanted to loosen his tie, but his reticence over producer interference emanates through a tired retread of the hits. It’s lit gorgeously (if only we knew how good we had it back in summer ’07) and loud enough to spark the generic blockbuster endorphin rush that keeps us tolerating the bullshit—plus, Raimi’s Spider-verse is still a quintessential, cozy creature comfort from the cheerier side of the 2000s’ escapism. But when a flick has such little light in its eyes, it’s difficult to vouch for its familiar merits with your full chest. Years are monumental when you’re in grade school. Every half year, you change teachers, classrooms, and daily faces. It is maybe the hugest cocktease for how your life will actually go when you’re a grown-up—the daily malaise of capitalist automation and order. You grow until you’re expected to not. I was a completely different person by the time SPIDER-MAN 3 was released. In 2004, my mom and I went to El Capitan after school to watch Disney’s HOME ON THE RANGE together. In 2007, I had to reach out to a distant cousin because she was the only one with the patience to take me to watch THERE WILL BE BLOOD. I grew up, but the SPIDER-MAN movies didn’t, and based on the overreaching maturity of SPIDER-MAN 2, it was clear that the franchise didn’t grow as Raimi had intended.

DR. STRANGE IN THE MULTIVERSE OF MADNESS (2022)

By the time a weary Benedict Cumberbatch asks “Why was that octopus trying to eat you?” in earnest, it is established early why Kevin Feige has made a brand out of exclusively courting low-budget directors into a hall of bureaucratic mirrors where imposter-syndrome-panic silently shifts the creative reins over to the execs who already have 70% of the movie pre-viz’d. If hiring Edgar Wright was deemed too much of a risk during the nascent era of the franchise, then there’s simply no shot that 30 movies in Marvel was going to hand off the steering wheel to anyone with a vision. Alas, here we are, with one of the most polarizing, clumsy installments yet. Raimi hopped onto MULTIVERSE OF MADNESS as a favor; the man has nothing to prove. And so he doesn’t really give a fuck about any of the MCU building blocks or the breadcrumbs (in this movie’s case: full stale loaves) leading to new multi-million-dollar star contra—wait, sorry, I mean exciting new heroes and lore! And what can Marvel do about the insolence? They literally invited him. What follows is a panicked, reshot-to-hell mishmash of a corporation’s forward steps and violent “why are you hitting yourself?” solipsism from a filmmaker who’s in it strictly for love of the game. Raimi brings comic book cinema back to its roots. No, not as American myth-making, but as dime novel writers guzzling diner coffee over their notebooks while cartoonists pump cigarettes by the carton to make the coloring deadline for tomorrow’s printing of “Tomb of Dracula.”

Mixing Sam Raimi’s good, fun, cool stupidity with the damning, toxic, insulting stupidity of The Walt Disney Company makes for something that’ll anger one side—the adult babies, the children, the lost—more than the other, which, hey, a rare W. If the Marvel Cinematic Universe is your primary religious text, then the ways this wastes incursions, Reed Richards, and the Time Variance Authority alone is enough to make you switch to the Snyderverse. Congratulations, dorks, your cinematic universe just gained its sixth high counsel of cosmic overseers: add The Illuminati to the pile alongside the Eternals, the Skrulls, The Watcher, The Ten Rings, and the Egyptian deities. You only exist in the MCU to be monitored by one institution more violent than the last, and also none of them work together despite having common goals. Remember when Hawkeye and Wanda were kinfolk? I sure am glad the gay pride flag exists in the completely alien universe America Chavez helms from. A two-part question, did Xotchl Gomez win a contest to be in this movie, and why did the RICK AND MORTY screenwriter intentionally sabotage this Latina teen with zero material?

MULTIVERSE OF MADNESS makes everyone who heralded the MCU as “revolutionary multimedia storytelling” and WANDAVISION as “a groundbreaking feminist treatise on grief” look like dipshit idiots, and caters to everyone who’d just like to pack a bowl and enjoy a dumbass summer movie about wizards, witches, and portals. A noble gesture, one punctuated by the euphoria of one of these widely-seen products finally getting to stretch its wings with visual dynamism and shock brutality, both striking enough that you can only cross your fingers that it converts some first-timers to chase the high, but it’s ultimately still a movie where 30,000 increasingly expensive things just happen for the sake of happenin—someone has to stop Kevin Feige from taking full advantage of a non-unionized VFX labor force, now more than ever. MULTIVERSE OF MADNESS is definitively a Raimi motion picture, but also feels weird to even include on the list, you know? I mean, it even feels a bit weird considering it as a completed movie. It’d be like including a Saudi prince’s personal recording of a private Yeezy concert on a ranking of Kanye West albums: this is a private, lavish commission by a voracious mega-power that we just happened to have stumbled upon.

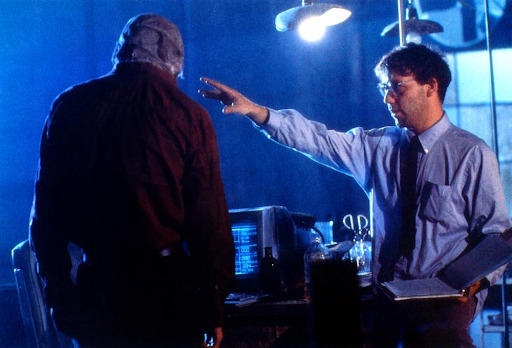

DARKMAN (1990)

Whereas the entire industry shifted towards mimicking the internationally beloved SPIDER-MAN, just a decade prior DARKMAN saw Raimi as passenger rather than conductor, feeding into Burton’s BATMAN mania as a means of legitimizing himself beyond “EVIL DEAD guy.” It’s home to each of his bona fides, but can’t help but feel harangued by its need to fit in by acting out. It’s a DICK TRACY’d ROBOCOP that doesn’t pick up full cartoony steam until its slow march to the 16-minute mark, where its brightest moments are slightly remixed Burtonisms or vague pitches for higher-tier work via the tenets of Genre Exercise 101. This might’ve felt far more refreshing in 1990, when these superhero subversions weren’t a dime-a-dozen, but if “Sam Raimi directing a self-created superhero revenge tale where the hero’s power is that he can make MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE masks” appeals to you, there’s no reason this shouldn’t be 90 minutes of your weeknight. Liam Neeson proves how rubbery and elastic his face can be before 30 continuous years of locking his jaw into place, and Frances McDormand reveals an alternate universe where she took jobs doing… Whatever this is! Brutal murders straight out of Troma, silent cinema storytelling devised as hallucinogenic visualizations, and a trailing ennui that’ll make you beg for any of these goons to mercy kill the titular hero, DARKMAN isn’t without its electrifying oddities, but it feels like a master chef putting pastrami and peanut butter on an Entenmann’s coffee cake then hawking it as their own. Weird for weirdness’ sake, and robust only to make the resumé sparkle some.

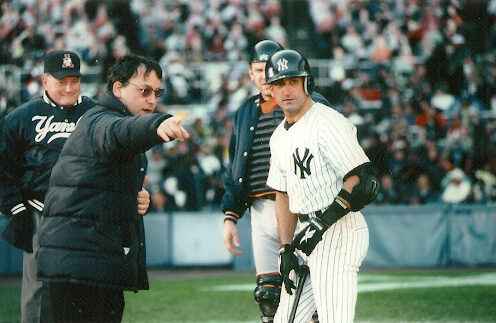

FOR LOVE OF THE GAME (1999)

The black sheep of the entire filmography, Sam Raimi’s sports movie is, surprisingly, not the worst thing he’s ever made! The most anonymous, the most depressingly reserved, and most pleadingly vying for a seat at the big boy table? Absolutely, and it’s a bummer to see an auteur this unique stoop to such plainness. A staid Kevin Costner romance that finds all its life in a hatred for the New York Yankees, and its celebrated star only springing to action when screamed at by a bleacher creature, and certainly not ever because he’s in proximity of the late Kelly Preston. Far more tantric is the relationship between Costner’s Billy Chapel and MLB rival Scarecrow, two men in separate cities who see each other on a strictly seasonal basis, but are the most important people in each others’ lives. No one knows it; neither do they. Costner’s pitching suddenly reads as emotionally erotic, Scarecrow’s stare down the mound strapping beyond belief. Without a doubt, enlisting in the army and playing team sports are the sole two socially accepted arenas for American men to publicly practice their intimacies.

Billy Chapel’s elegiac, final no-hitter game set to Dylan’s “I Threw It All Away” is a double-edged sword: though one of Raimi’s finest setpieces, it’s the proving ground for his decade of prevailing crowd-pleasers, a decade that blasts off until it Amelia Earharts into the fucking floor with OZ. If he can stir the masses while keeping the camera still, then there’s hope in an executive’s heart that they can harness a tamer version of the director—and that they do. Eventually, Raimi becomes comfortable with it, too Chapel’s actual final game, where lens flares stand in for God’s light and the expertly sound-designed stadium thumping roaring through even a TV speaker, is grandiose location filmmaking. With the full orchestra blasting, the film formats shifting between 35mm and live feed broadcast, and a dozen New York character actors sweating from their temples, it’s the closest white folks have gotten to their own HE GOT GAME. At its worst, which is its majority, it’s tailored for fellas whose refrigerators house little more than mustard, fish sticks, and a big jug of V8 juice.

CRIMEWAVE (1985)

The lost Sam Raimi movie, the one he and former roommates Joel and Ethan Coen have banished from their records, CRIMEWAVE makes complete sense as a follow-up to THE EVIL DEAD. Sure, there’s a plot, but the atmosphere is thick with opportunities to explore the extremities of genre. Those extremities? Extreme violence, of course. It’s definitely a noir parody caper by the EVIL DEAD lads. Overtaken by producers, and all the more incomprehensible for it, the only reason to preserve CRIMEWAVE as a curio, and not just chuck it in the bin, is for its backhanded virtues. Seeing Bruce Campbell flop every one of his deliveries only makes his repeated tour de force as Ash that much more magnificent. Watching the Renaissance Pictures boys pull off a DICK TRACY aesthetic with a fraction of Beatty’s budget is charming as long as you look past how out of depth they were on how to light and frame it as comic strip maximalism. It visually flounders like an 80s Tom Hanks comedy with infrequent flourishes of brassy colors rather than the transportive bedlam of James Cagney and MAD Magazine they promised producers it would be. The comedy meter is set to “default,” and even so, it’s doing the pit-bottom least by doing the obnoxious most. There’s so much here that calls to mind Peter Jackson’s early exploitation (ex: BAD TASTE, MEET THE FEEBLES), but it’s so fussy that it can’t retain the same charm of setting a movie in a world of pure violence when the violence is the type that’d make your grandmother yawn. CRIMEWAVE is molded with a humane, handcrafted goofiness: it’s made by humans. And that’s what makes it hurt the most. In 2022, it’s a blight calibrated for perspective on the treacly nature of authorship. All it takes is a few loose screws and a couple rotten boards to capsize the hull. It’s an early omen of Sam’s struggles to come, ones that persist even today. A Coen Brothers movie is kind of shitty if you don’t let The Coen Brothers be The Coen Brothers. And a Sam Raimi movie is pretty fucking bad if you don’t let Sam Raimi be Sam Raimi. Listen to the fellas.

OZ THE GREAT AND POWERFUL (2013)

I’m ecstatic that Sam Raimi directed DOCTOR STRANGE IN THE MULTIVERSE OF MADNESS only because it means OZ THE GREAT AND POWERFUL will not end up the final film he ever made. If Sam Raimi caught early 2020 COVID and died before he could rinse the flavor of OZ from his record, there’s no doubt in my mind that it would’ve been the greatest cinematic tragedy of our times. What’s there really to say about a 2010 ALICE IN WONDERLAND rip-off by the company who bankrolled 2010’s ALICE IN WONDERLAND? It certainly asks the bold question of what if your $215 million blockbuster looked as bad as SPEED RACER but wasn’t SPEED RACER. James Franco is an unforgivably bad lead, and Mila Kunis is so immeasurably worse that her turn as The Wicked Witch of the West calls into question how she ever got tossed into movie star consideration in the first place. OZ is the type of failure that doesn’t just make you think an artist is past their prime, it’s the calamity that makes you question the validity of their successes. The only explanation for how dismal this motion picture is must be that the filmmaker, in fact, never actually knew how to make a motion picture! A discolored, garish sore on the eyes, mind, and heart that offers the same delusional mental-illness-activation as ayahuasca does, OZ THE GREAT AND POWERFUL is a Raimi-for-hire gig so grueling that it stretches his credentials as a man of esteem over a drum of acid. It might be one of the worst films ever made, Raimi’s attire indistinguishable from the Disney suits who, I must repeat, cynically greenlit an off-brand retread of their own property. In the dawn of The Walt Disney Company’s monopolization of IP, OZ THE GREAT AND POWERFUL lays criminally bare how complicit one of cinema’s coolest folk heroes was also a key player in the cultural downfall we bemoan today. Sammy-boy’s got some layers to him, I’ll tell you what.

Comments