As a kid, I spent summers attending a sports camp put on by the city. From 8AM to 1PM at a park down the street from my house, I would play dodgeball and capture the flag and basketball. For a lot of kids, it was a place to get dropped off when their parents were at work, but for my brother and I, we just liked playing sports with our friends. The entire camp was run by cool people in their early-to-late-20s, many of whom worked for the parks department, some of whom were in college, and some of whom were sleeping together, although all of this merely a guess given that when you’re eight or nine years old, age and relationships are simply vague, abstract concepts. Two of those counselors, Steve and Randall, had a strangely profound impact on me at that age, both slick, cool, funny dudes who I genuinely wanted to emulate when I grew up.

But here’s the thing: I only knew Steve and Randall in the context of going to sports camp over the summers. For six years, they were constants in my life which in retrospect is pretty wild, but then I grew up and they just… went away. One year we saw Randall outside of camp, during the school year, and I didn’t know what to do. It was like deja-vu-ing a person to life somehow. And to this day I think about both those guys and wonder if they were the cool, young, partying dudes I ascribed them to be when I was a kid, or if they were actually wholesome, or douchebags, or burnouts, or maybe somehow all three.

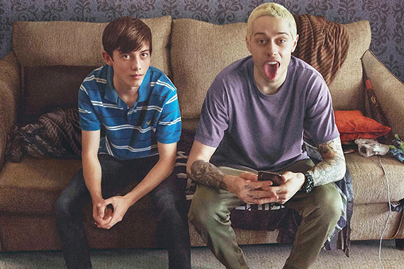

If you take one look at this picture and decide the movie is not for you, honestly that’s totally fair

Pete Davidson’s Zeke Presanti was a counselor I had as a kid. That dealer’s choice question of if he’s wholesome, douchey, or a burnout? That’s the tightrope Davidson and writer-director Jason Orley are walking across BIG TIME ADOLESCENCE, finding a way to make us somehow buy into the SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE playboy as a worthy source of childhood commendation and aspiration, and it’s a tightrope walk that the two pull off somewhat successfully. For 90 minutes, we are put in the shoes of the young Mo Harris (Griffin Gluck) and expected to buy into Zeke as a cooler, older energy worthy of influence both good and frequently bad. That’s an experience that’s sometimes funny, sometimes cringy, and sometimes pretty heartwarming. The film opens on Mo getting arrested before rewinding and showing us how a relatively well-adjusted kid could end up in handcuffs. That moment fortunately isn’t played as a very special episode, and instead Orley keeps that scene in the back of our minds for the rest of the film, making that tightrope walk even more impressive.

If BIG TIME ADOLESCENCE works at all, it hinges on two things: 1. Your ability to see Pete Davidson as anything other than a relentlessly obnoxious comedian, to which your mileage will obviously vary, and 2. You personally having had a similar kind of influential relationship, for better or perhaps worse. And that’s a complicated kind of relationship to depict on screen. Regardless of if it ultimately works fully for you, the depiction of Zeke and Mo’s relationship is worth commending; the influence a simple age gap can have on kids or teens—frequently depicted as the influence Seniors have on Freshman—is often a turn in plot, not the focus on an entire movie (see: EIGHTH GRADE, SUPERBAD). If you ever had the admiration for, or were influenced by, a Zeke type, then something about BIG TIME ADOLESCENCE will likely seem endearing.

I’ll be totally honest: Didn’t hate Machine Gun Kelly in this movie. I’ll go ahead and cancel myself on my way out the door

The film’s MVP ends up being Jon Cryer, whose role as Mo’s dad can best be described as having strong “I’m not mad, I’m just disappointed” energy. Watching Cryer juggle being an authority figure with the existential question of why kids are drawn to the things or people they are is pretty masterfully executed, and Orley goes as far as to question who has a bigger ultimate influence over Mo, his father or Zeke. The full realization of that question, watching Mo’s father confront Zeke, is the film’s high point, and ultimately it’s an intentioned question in a film that could use more of them. A movie that relies this heavily on Davidson’s charisma and charm is a huge gamble, and Orley never gets around to establishing an actual story, simply going through the motions depicting the bad influence one mid-20s ne’er-do-well has on a vulnerable high schooler until things eventually boil over while keeping that opening arrest scene in the back of our brains. The partying and navigating adolescence begins to feel repetitive by the time we hit the final stretch, building towards that opening scene—despite the 90-minute run time, that first 45 minutes feels pretty aimless, more a slice-of-life vibe where the film slowly chisels away at the question of whether or not Zeke is wholesome, a douchebag, a burnout, or somehow all three, the answer to witch becomes stretched pretty thin by the end.

I wonder frequently what happened to Randall and Steve. Steve I know went on to work on a used car lot, which honestly fit his personality fine—that I thought that was a kind of interesting, cool career path for him at 13 says both a lot about me and a lot about Steve. Randall though I’m not sure, although I pray he doesn’t wear puka shell necklaces anymore. Typing out those last two sentences I of course have to question what was cool about the two in the first place (it was the 90s!), but ultimately we have no say in how the magnetism of older people will sway or influence us when we’re kids. The question of Zeke’s true character, and his hold over Mo, makes BIG TIME ADOLESCENCE worth watching, but that doesn’t mean that magnetism will work on you.

Comments